See the cover of SPACE No. 41 (Arpil 1970)

Is anyone easily persuaded that the designer of this extraordinary house, the Residence of Mr. Kang, is Yoo Kerl (born in 1940), also the designer of the new Seoul City Hall building? To young architects in their 30s and 40s, myself among them, Yoo Kerl’s work is imprinted on our consciousness as free form based on unconventional thinking. Why does geometrical precision, which borders on obsession, and a closed stylistic system, appear fundamentalist, as opposed to one of a freer spirit as he was once known and understood? As such, the question arises as to what kind of relationship this small house, which he designed at the age of roughly 29, has with the established name of the ‘architect Yoo Kerl’, who has now left a number of significant impressions on the Korean architectural world.

SPACE No. 41, p. 43.

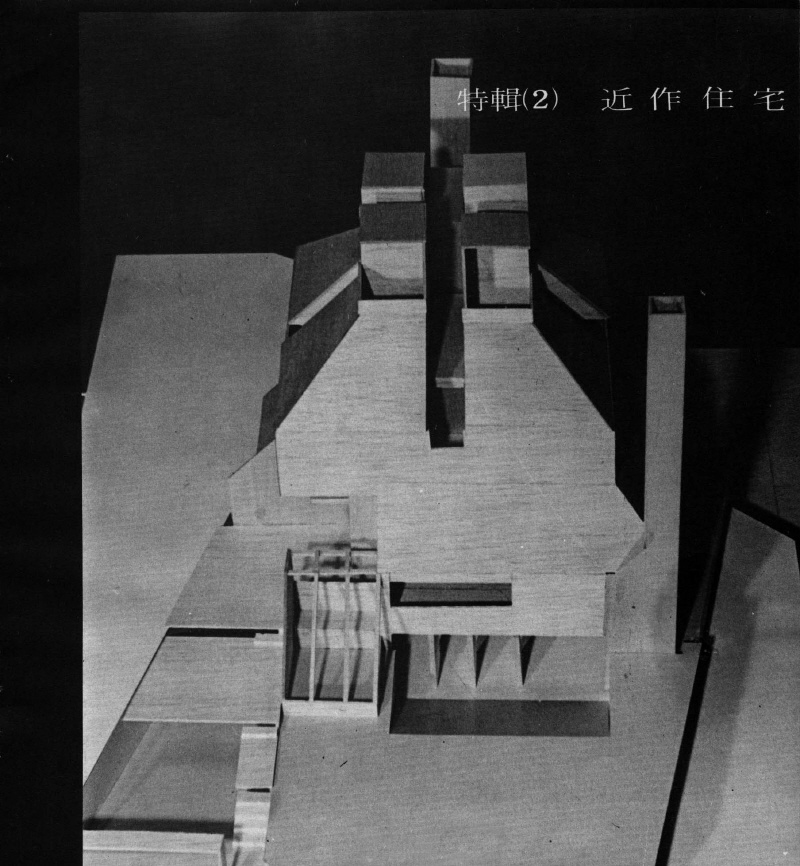

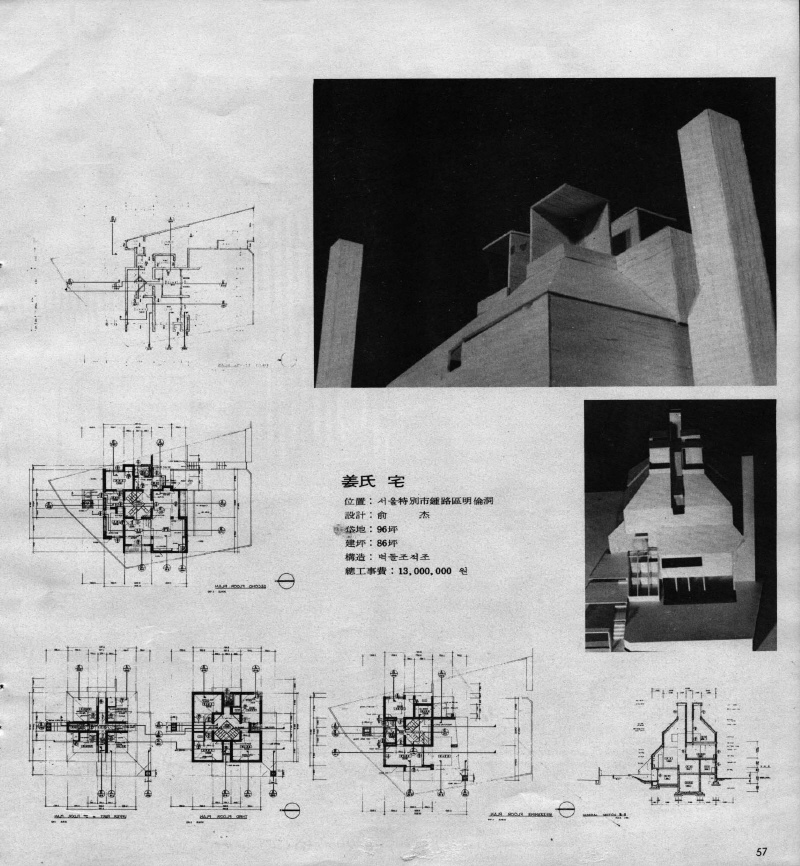

This house (featured in SPACE No.41 [Arpil 1970]) appears to have been influenced by American architect Louis Kahn, and was designed and finished between 1969 and 1970. In his oral history book, which was published in 2020, the architect reflected on his interest in Louis Kahn at the time. Not to mention the concept of Served Space/Servant Space, it almost looks as if the 9-square plan of Trenton Bath House (1955) and the roof and lighting style of the First Unitarian Church (1969) have changed their forms. We could even refer to more distinctive prototypes, such as John Hejduk’s Texas House series or Andrea Palladio’s Villa Rotonda, but given the circumstances of the present time, when people had extremely limited access to resources, it is difficult to say whether they were direct references. At that time, Yoo Kerl left his job at Kim Swoo Geun Architecture Institute after three years and began working as a freelancer at Kim Swoo Geun Architecture Institute while also pursuing personal projects in 1967. A series of house projects completed before his move to Denver, US, in 1970 but that was not well known by the public, reveal his unique architectural interests and are meaningful works in terms of the legacy of both the architect himself and for the history of contemporary Korean architecture. The houses that the architect noted as the most memorable were Jeongneung House (1969), the Residence of Mr. K in Seongbukdong (1967), and the Residence of Mr. Kang in Myeongnyun-dong (1969), which were more consistent than anyone else at the time with a formalist attitude. They are presumed to have drawn greater influence from Kim Swoo Geun than from Louis Kahn, as previously mentioned. When Kim Swoo Geun first saw Yoo Kerl’s clay model of the Constitution Hall, which he designed for the first time after entering the Kim Swoo Geun Architecture Institute in 1965, Kim Swoo Geun told him, ‘I can’t sell these kinds of things, so do it later when you open your own office’. This is a well-known anecdote that caused Yoo Kerl to deliberately avoid taking an artistic approach for several years afterwards. However, is it possible for this nature to be erased or obscured so easily? Yoo Kerl was born into a family of artists, so he might have devoted his artistic ambitions to the life of a sculptor, but he opted to become an architect for practical reasons thus presenting projects that are both mathematical – which can be referred to as ‘the mathematics of the formal villa’ – and also sculptural. On that account, the Residence of Mr. Kang, which has both a clear style and sculptural form, is known as a rare masterpiece that strikes a balance between sense and sensibility. The Residence of Mr. Kang is in the series of Jeongneung House, and while Jeongneung House is a single-storey house; both houses share the same concept of seeking an underlying geometric order. However, the fact that the Residence of Mr. Kang is not his own house, as a three-storey building, and that the client has a more complicated family make-up, makes the house all the richer.

SPACE No. 41, p. 57.

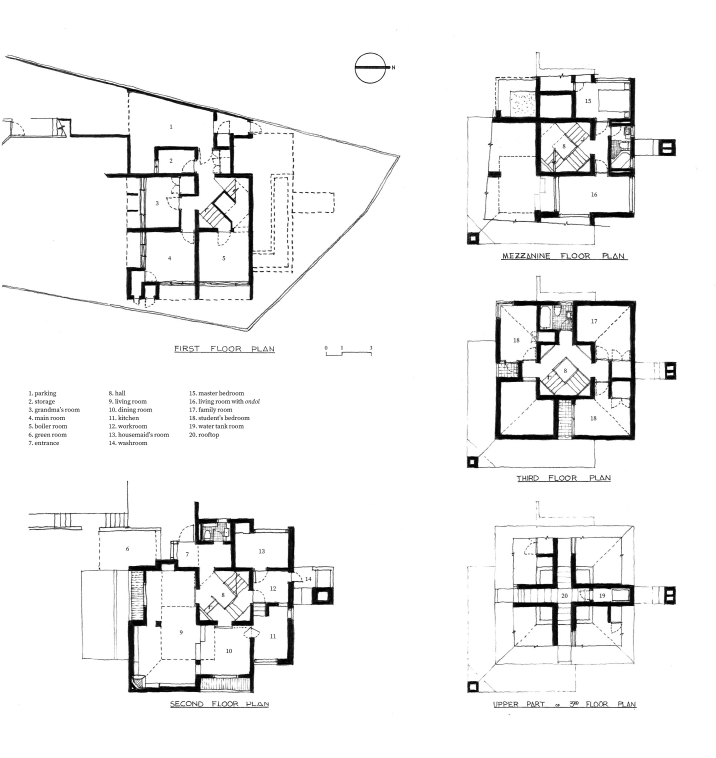

While the most prominent part of the Residence of Mr. Kang is thought to be its conventional plan and form, what is more profound in terms of its meaning and significance is the scent of the house. Aside from the site’s irregular shape, the house is perfectly aligned with the four cardinal directions. Furthermore, the symmetrical and complete form, with its towering chimneys at both ends, resembles a mosque-like temple. In this way, it is difficult to uncover the old-fashioned rhetoric of Korean architecture, which is an ‘adaptation (obedience) to the site’, and this provides a clue to the values that inform his design context. Later, in an interview with the mokchon kim jung sik foundation, the architect noted that the morally enforced idea of devising ‘harmony with the surroundings’ in Korean architecture is a bad way of suppressing individuality and promoting homogenization, which is consistent with the individualism of which he has spoken as a guiding principle in his designs. That is not to say that the layout of the Residence of Mr. Kang is unreasonable or bombastic. The building, which was boldly placed in the middle of the site while completely blocking the north and south, separates the exterior space based on functionality. In the back yard on the north side, there are service spaces such as a chimney, a washroom, a workroom, a housemaid’s room, a kitchen, and storage spaces, whereas, in the sunny south yard, there are living spaces such as green room, living room, and main room. As a result, not only is the circulation clearly separated, but the building also sits peacefully on the ground, as if a wide skirt has been unfurled.

Plan sketch (drawing: Suh Jaewon)

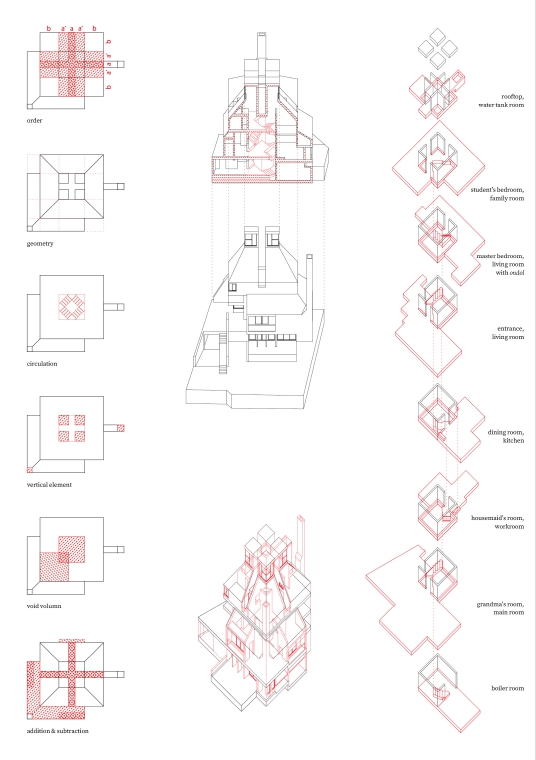

The 9-square grid of the plan is not as simple as one might think. If the cross-shaped grid (a) connected by a diamond staircase angled at 45 degrees arranges the layout of the servant space throughout the house, then the rooms in the four corners (b) naturally become served space. The process by which semi-servant space (a’) responds, as in an extension of a room, a void, a bathroom, or a closet according to each context, at times demonstrates the architect’s considerable restraint and composure. The present writer admits to being touched at the point where the water tank is placed in the cross-shaped space on the rooftop, dividing the roof into four. In the case of a complete form based on such an internal order, its innocent form and system are prone to breakage during the process of resolving functions. In the case of the Residence of Mr. Kang, the project appears to have faced just such a challenge in securing the living room area. However, the architect seems to apply the system to its fullest extent even while also maintaining the system to a reasonable degree. Such is the case with the basic 9-square grid centred on the central staircase, which overlaps into two 9-squares by duplicating on the second floor plan where the living room is located. This system extends to the first floor, and it even achieves new logic by incorporating a garage on the west side. Perhaps the storage space adjacent to the garage is likely to be the driver’s space. The two overlapping grids that are tilted in this manner finally reveal their purest form on the third floor. There is also a way of getting rid of the secondary masses that add up to the second floor to address a more practical problem, revealing the true form of the body and resulting in a single entity with a 45-degree sloping roof. Nonetheless, this masochistic approach, ruthlessly dividing the roof into four equal parts, is as mannerist as Luigi Moretti’s Il Girasole (1951). To establish unity, the additional form features a sloped roof at the same angle as the three-storey roof. The void volume is likewise expressed on the inside, and the two resulting columns are the only interstitial elements that appear throughout the entire plan and serve as a point of visual enrichment in the space. Yet, the space beneath the sloping roof, which connects each room on the mezzanine, appears to be storage that was created inadvertently by matching the style and form, while the void above the entrance hall, where no light penetrates, is a little unfortunate. This house in general has a lot of deep closets, which is probably an unavoidable outcome of placing the modules together. In particular, it is apparent that the narrow closet in the student’s bedroom on the southwest side of the third floor, as well as the bathtub being rotated and diagonally positioned in the bathroom layout on the mezzanine, are the result of balancing style and function.

A living room on the second floor. 1:20 model (production: Bak Sunmin)

A family room on the third floor. 1:20 model (production: Bak Sunmin)

It required a lot of thinking to figure out the best solution to introducing the window openings on the exterior of this house; even this must have been done to ensure the overall formal aspect and character while also achieving a dramatic impression of light cascading from the roof ’s clerestory. This is especially true of the third floor, as there are no windows visible from the outside except for the corner windows and bathroom windows in the student bedrooms. All large windows appear on the side of the terrace pierced in the roof, without interfering with the overall form. As a result, these dimly lit rooms with limited light are accorded the tone and register of a chapel through the gentle dispersal of the light pouring in through the clerestory at the top of the sloping ceiling throughout the space. This is the moment to wonder what type of person the house’s owner was. Another noteworthy feature is that the solid wall defining the staircase does not extend all the way to the sloping roof. As a result, the light from the clerestory comes from neither the servant space nor the served space. In the end, a meticulously maintained stylistic order is softened with light and integrated into a single space. The fragmented roof is the inevitable form of a master’s strategy for adding an element of the unexpected.

Overall, the house was made of bricks, tiles, and a tiled roof, just like those in its surroundings. The symmetrical shape also plays a role, but due to the heaviness of the bricks, it looks like the Stone Brick Pagoda at Bunhwangsa Temple or like an object like a jewellery box. It is difficult to find any superficial similarities between this house and the works of ‘architect Yoo Kerl’. However, this house’s distinctive sense of artistry and spirit of resistance appears to be the same as the Yoo Kerl we know and admire. The present writer was able to access a wide number of publications on the architect in order to write this article, but none of them could encapsulate him in a single sentence. The only thing that can be done is to express gratitude and respect to a senior architect who left such valuable work more than fifty years ago.

In our next issue Cho Hyunjung will cover ‘Contemporary Architecture in Japan’, which featured in SPACE No. 9 (July 1967).

* note

The address of the Residence of Mr. Kang is 206-2, Myeongnyun-dong 4-ga, Jongno-gu, Seoul. It is thought to have been completely demolished around 2013. The original structure can be found in black and white photos on page 107 of Yoo Kerl’s Oral History Book, published by MATI BOOKS. The approximate three-dimensional form can be found in 3D by using Kakao Map’s 3D sky view and also by tracking the 3D building and image map back to 2013 on S-Map. The plan sketches drawn by the present writer were prepared for more accessible viewing by referring to the drawings published in the April issue of Architect in 1970. For your information, the entire external box is 8.7m × 8.7m is based on the third floor plan, and the staircase is 3.5m × 3.5m.