Editorial team, ‘A Critical Estimation on Post-modern Architecture’, SPACE No. 261, pp. 32-33.

Although SPACE was not active in covering political and economic change on paper, it was impossible to be incognizant of change and fluctuating fortunes in 1989. Rapid developments and pivotal events took place, such as the Democracy Movement in 1987, the Seoul Olympics in 1988, and the collapse of the Soviet Union and the socialist countries of the Eastern European bloc in 1989. In July 1988, SPACE prepared an ambitious, year-long plan entitled ‘The Modernization of Korea and Environmental Culture’. This plan begins with the following diagnosis: ‘Unfortunately, the process of Modernization was not a spontaneous change based on the awareness of Koreans, but based on a heteronomous change carried along by the rapidly changing situation in Korea […] During this process, traditional society collapsed and different phenomena such as the decline and replacement of the leading roles in culture, annihilation, and distortion of indigenous cultures, and the inundation of multinational and foreign cultures occurred, resulting in a unilateral and passive “progressive assimilation” of culture rather than spontaneous and proactive “acceptance” of culture’.▼1 Through keywords such as reform and acceptance, tradition and the foreign, it is possible to countenance the atmosphere of an era in which unfamiliar and new things shake its foundations, as well as the direction of a basic problem on which project is premised. The seventh special feature was ‘A Critical Estimation on Post-modern Architecture’ in SPACE, No. 261 (May 1989).

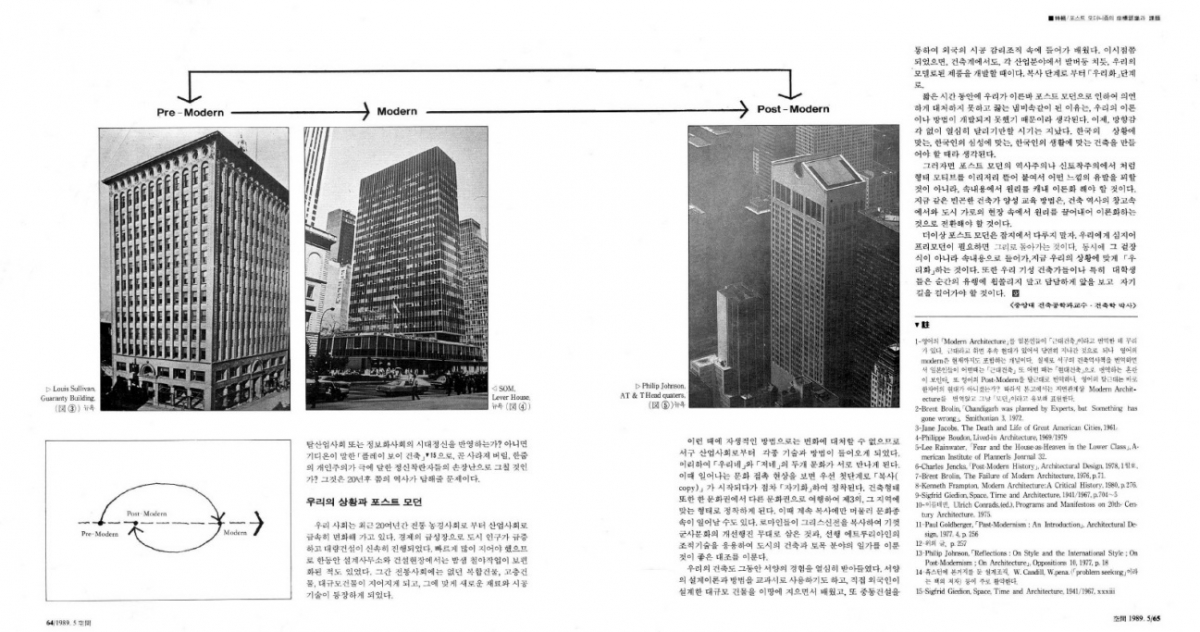

In the early 1980s, postmodernism emerged with the rise of a certain kind of architect (such as Kim Kiwoong) who adopted elements of form from traditional architecture or students (for example, Yang Namchul, Choi Yoonkyung, and Lee Hyunsoo: the winners of the first Open Competition in the National Exhibition of Korean Architecture) who had a keen eye for popular trends and used them as the basis of their projects. In the year 1987, when postmodern discourse burst like a flood, postmodernism, which was discussed on a personal level or considered as neutral/optimistic as a new trend in overseas architecture, faced a new era. At this moment, the debate concerning postmodernism in architecture, like any other post-discourse, began to probe the premises of the post and what makes it feasible, along with the peculiar nature of post theories. In other words, in order to speak about postmodernism, a discussion of modernism must take place in some form or be acknowledged. We should never forget that the special feature on postmodernism in SPACE was also prepared based on a sketch of the process and progress of ‘modernization’ in Korea.

At that time, it can be asserted that no one in Korea was in the position of misunderstanding modernism-postmodernism as a linear temporal logic (commonly referred to as Hegelian-Marxist). Unlike modernism, which was established with a specified goal (encouraged by external influences) to pursue individual value judgements, postmodernism itself did not prioritise a given value that needs to be pursued. Modernity was something that could be completed or achieved. Democratic movements and reformations in different fields in 1987 were oriented towards a specific goal, and this had a close affinity with the logic of modernity. Whereas modernism enabled a clear logic for different camps, postmodernism – which is rather relativistic – blurred the distinction between entire camps. Hence the Marxists, who deemed the transitional stage of history as the law and believed in the sole centre, were more hostile to postmodernism than anyone else. Although the influence of Marx was not as dominant as in the social and human sciences, the field of architecture was in a similar condition. For architects who did not think of architecture as an autonomous discipline and that it lacked sufficient developments in engineering and technology, accepting postmodernism was not just the simple matter of accepting a formal language. In many aspects, the institutional, technological, and the expository, modern architecture was simply a set of values to be achieved. Postmodernism in the 1980s and 1990s was, without exception, something that took place (or must have taken place) after modernism. Although we have endlessly make reference to François Lyotard, it was impossible at that time for Korean readers to understand the core thesis of Lyotard, which is that postmodernism resides within modernism, that postmodernism is a void within modernism, and that modernism cannot reach an endpoint.

Lee Heebong, ‘Post-modern Architecture: Is it What We Need?’, SPACE No. 261, pp. 60-61, 64-65.

For the special feature in SPACE, the contributions of Yim Changbok, Sohn Seikwan, Do Changwhan, Lee Heebong, E Ilhoon, Park Kilyong, Lee Yongheum, and Kimm Jong-soung were published. This is such an extremely talented group of authors. Other than discussing the characteristics of Korean and postmodernism, I wonder if there is any other topic that could bring them together in a single tableau. To that extent, postmodernism was a powerful subpoena to summon everyone, and a litmus paper to gauge the awareness and identity of the respondent. Of all the authors, Lee Heebong took the most hostile stance towards postmodernism: ‘Rather than provoking a certain impression by taking a motif from a form as in the historicism or neo-nativism of postmodern, one should theorize it by extracting the principle from the inner content […] Let us no longer cover postmodern in the magazines’.▼2 It is an overly resolute position, but such a stance was not unusual. Yoo Kerl, who more than any other contributor supported new technology with an open attitude, stated that ‘Postmodernism, which seems trivial and absurd, can only resonate when it is based on Modernism, which is intellectual and ordered. But without the cold, rational, and absolute “contemporary” that they intended to cope with, this anticontemporary ends up as a lunatic act’.▼3 Kimm Jong-soung also insisted on returning to Modern. ‘The most important component of contemporary architecture is “space”, and it is necessary to reconsider what else could have been if, historically, the realm of architecture was not the one that created “space”. […] In other words, it is the vocation of architects to return to the pure architectural values and evolve Modernism’.▼4 It is an argument that, while postmodernism is about the coding and decoding of language formed on the skin of architecture, we need to scrutinise; how does modernism embrace ‘space’, the essence of architecture. Of course, not everyone claimed that it was crucial to grasp modernist principles while pushing postmodernism aside. Although there were few, other voices did emerge. Do Changwhan welcomed postmodernism, saying that ‘this “-ism” is the discovery and invention of a new concept for this era. This is a characteristic of both the Korean and the oriental’.▼5 A list of statements that expressed positions on postmodernism from across media outlets, including SPACE, could become quite long. Examining the entire list is beyond the space given to this article. To put it simply, as it reached the early 1990s, the governing discourse of Korean architecture ended up reconfiguring modernism, despite differences in individual opinion.▼6 In this way, postmodernism in architecture is reduced to a narrow and clearer definition that refers to an architecture that borrowed and satirised elements from more traditional architecture. The connections to postmodernism in the broadest sense, including flunctuations in historical, political, and social matters were gradually blurred. The hegemony was reorganised by setting the post aside, in addition to a discourse that had become monotonous and familiar, have continued to this day for 30 years. This is also the reason why a reinterpretation of postmodernism goes beyond historical significance. This evaluation is yet to be made.

Kimm Jong-soung, “A Critical Acceptance of Post-modernism and a Role for Architects”, SPACE No. 261, pp. 78-79.

In our next issue, Suh Jaewon will cover ʻResidence of Mr. Songʼ by Cho Sung-Lyul, which featured in SPACE No. 79 (Oct. 1973).

-

1 Editorial team, ‘Initiating a long-term project, “The Modernization of Korea, and the Environmental Culture”’, SPACE No. 251 (July 1988), p. 89.

2 Lee Heebong, ‘Post-modern Architecture: Is it What We Need?’, SPACE No. 261 (May 1989), p. 65.

3 Yoo Kerl, ‘A Treatise on Post-modernism’, PLUS June 1988, p. 97.

4 Kimm Jong-soung, ‘A Critical Acceptance of Post-modernism and a Role for Architects’, SPACE No. 261, p. 79.

5 Do Changwhan, ‘A Changing World-View and Post-modernism’, SPACE No. 261, p. 53.

6 The 4.3 Group, which secured the hegemony of architectural discourse in the early 1990s, resulted in the rediscovery of Modernism, despite the different stances of each member. Regarding this, refer to: Park Junghyun, ‘From Plaza to Boudoir: A Turning Point at the Early 1900s’, Papers and Concrete, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, 2017, pp. 50 ‒ 57.