The cover of SPACE No. 62 (Mar. 1972)

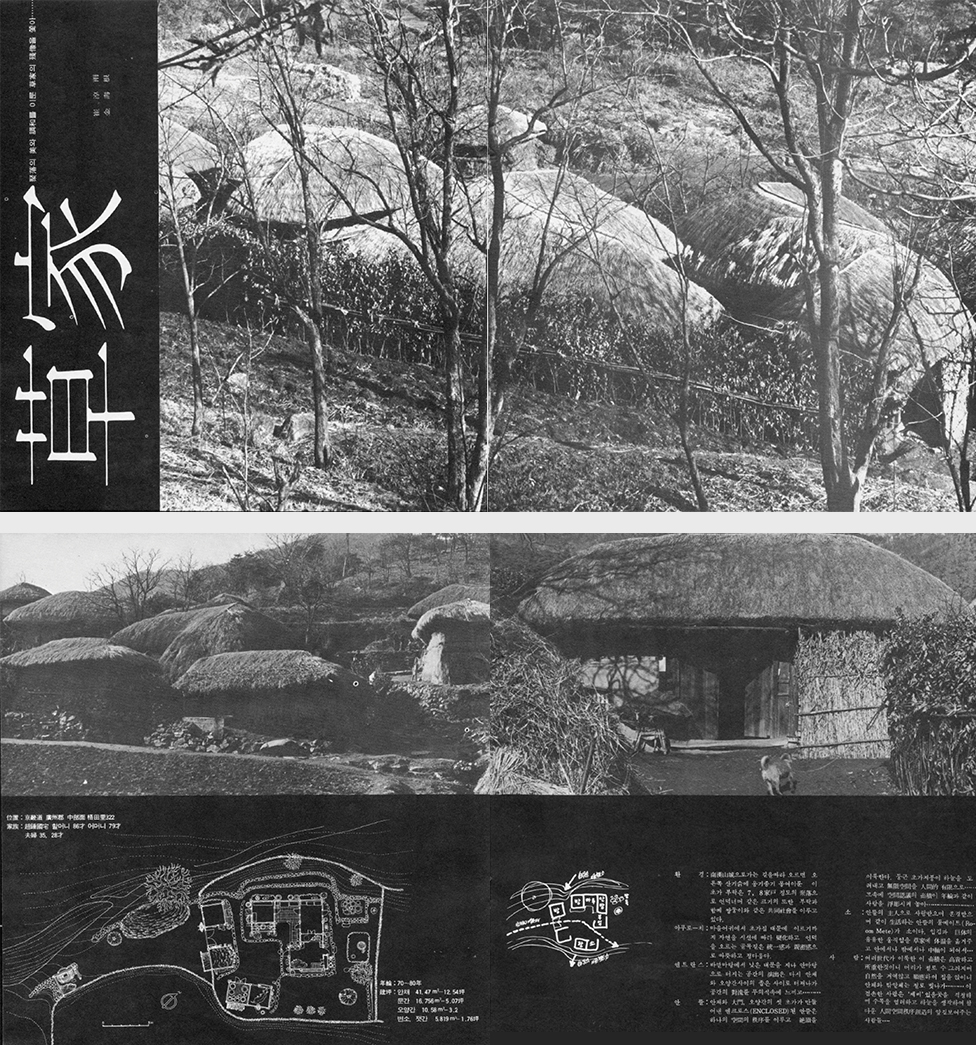

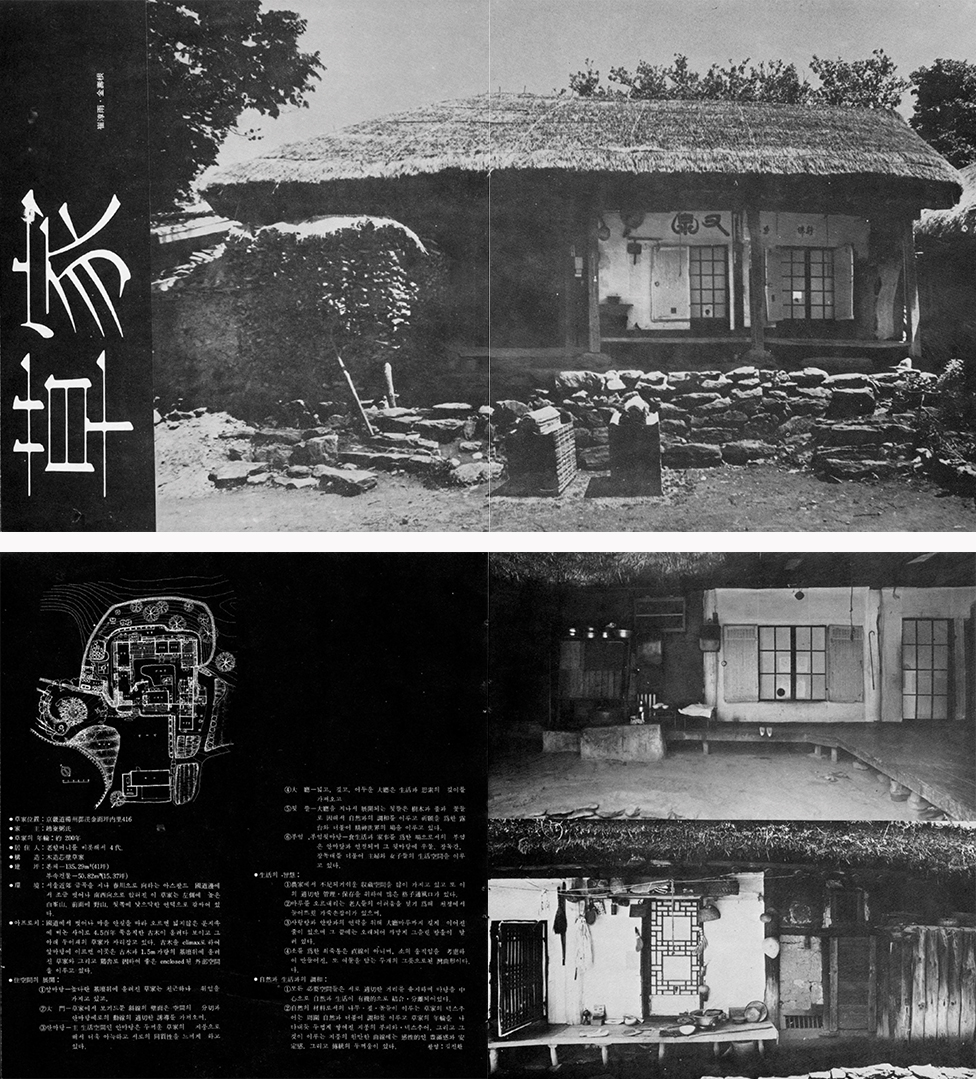

In 1972, SPACE featured a series of photographic essays on the theme of the Korean traditional thatched-roof house (choga) over five issues (No.62, 63, 64, 67 and 68). The series, convened by Choi Sunu and Kim Swoo Geun, begins with a short introduction to the maeul (Korean traditional village), continues with plans and simple field survey documents, explores the generic rural homes of Korea by following a logic of ‘environment ‒ approach ‒ entrance ‒ courtyard ‒ cattle ‒ people’.▼1 It was the first time in the history of SPACE that the history of the thatched-roof house had been selected as a topic for a special feature. From the first edition in 1966, which featured urban planning of Seoul, the primary focus of SPACE had been emerging urban environments and lifestyles, without any obvious interest in the rural. While the modern high-rises of the city centre were welcomed as exquisite accomplishments redolent of a plentiful and future oriented modernisation, the built environment of the rural, especially the thatched-roof house, was considered to be a relic of the unsanitary and impoverished pre-modern, and therefore excluded from mainstream representation. Ironically, the built environment of the rural became a new object of interest as traditional houses and buildings began to disappear due to the Saemaeul Undong (New Village Movement). Saemaeul Undong, announced and executed under the banner of modernising the countryside by the Park Chunghee administration from 1971, rapidly replaced the rural thatched- roofs with housing of ‘modern’ and ‘urban’ slate and galvanised steel roofs. At this time, the foremost sentiment that emerges from the thatched-roof house features in SPACE was that of serenity, as if time had stopped, derived from a sense of affection towards one’s hometown and a feeling of nostalgic sorrow about that which was fading from view. The pleasing and familiar depictions of countryside scenes have long acted as counterpoint to the fractious nature of urban life, rather than portraying deprivation or poverty that often characterised rural life. In the captions of the photographs, the rural is lyricised as an ideal, one undifferentiated from the natural world: ‘good to have water / good to have cattle / good to have the greenery / good to have the sun’.▼2

Choi Sunu·Kim Swoo Geun, ‘Korean Traditional House’, SPACE No. 62, pp. 18 ‒ 21.

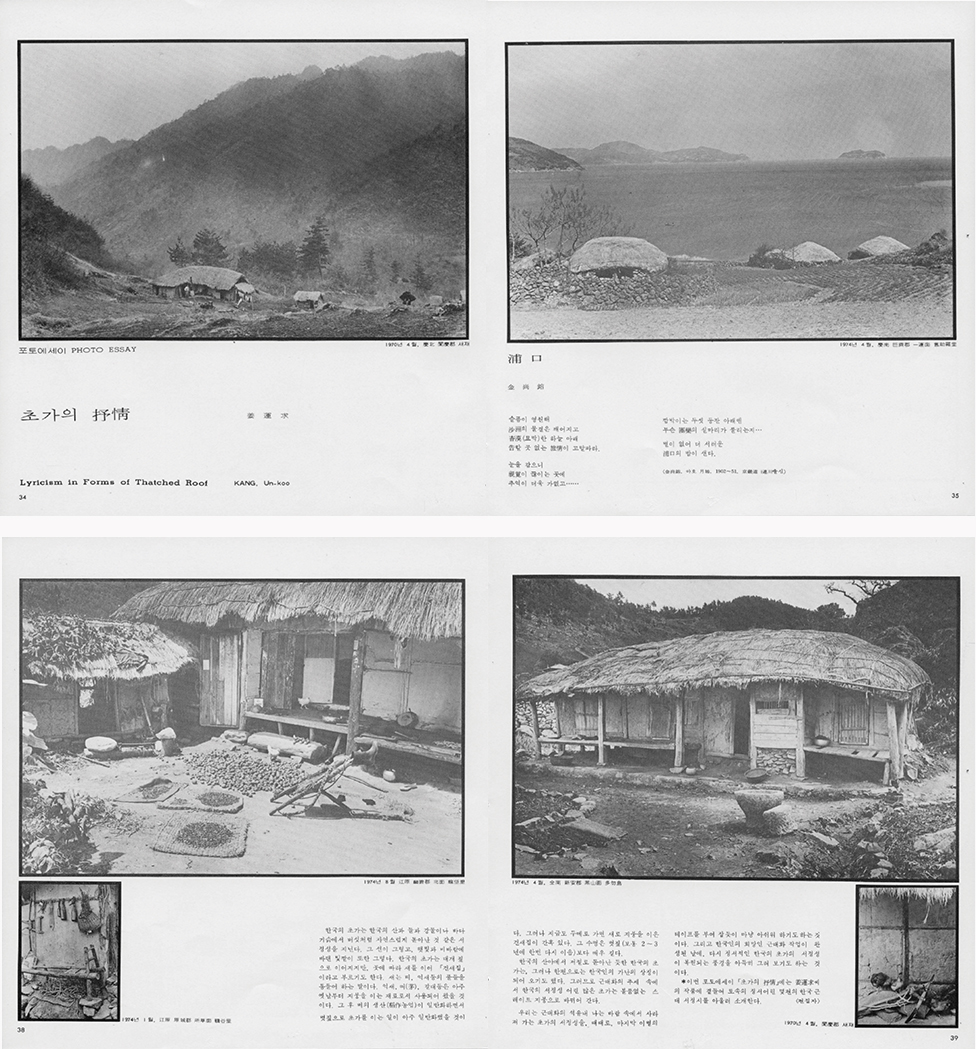

Such a poetic and romantic representation of the thatched-roof house can also be found in the rural scenes captured by the photographer Kang Un-koo, from around the same time. Village photos by Kang were featured in the early, mid and late 1970’s in magazines such as Shindonga and Ppurigipeun Namu (Deep Rooted Tree), as well as in exhibitions, and also published under the headline ‘Lyricism in Forms of Thatched Roof’ in SPACE No. 109 (July 1976), reigniting a sense of nostalgia for urban readers who had left their hometowns behind. Such lyricism contrasts with the agricultural literature of contemporary novelists such as Kim Jeong-Han or Lee Mun-Gu, who possess a more critical eye in terms of social class and minjung (the public) concerning rural issues, highlighting the destitution to be found in the countryside destroyed by the fall out of a crippling rate of modernisation. The thatched-roof house series by SPACE must be understood in tandem with the research trend for traditional folk house (thatched- roof house), which cropped up in many fields from the 1970s. This is not only from the perspective of architecture, but also of folk studies, geography and archeology. If studies of the traditional folk house had taken place in the form of preliminary studies for colonial domination by Japanese scholars during the Japanese Colonial period, the rising trend for traditional folk house which re-emerged in the 1970s came to locate itself within the nationalist (minjok-centred) plan to recover the origins of Korean residential architecture. Cognisant of the threat that Korean pre-modern rural culture may become extinct, there was a surge of interest in traditional lifestyles and cultures. The boom for traditional folk house was also notable in Japan, which experienced its phase of rapid modernisation and urbanisation a little earlier than Korea. As the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties as amended in 1954, to protect cultural heritage sites in Japan covered temples, Shinto shrines, the mansions of aristocrats also covered the traditional folk house, the traditional folk house became the object of major research projects, preservation activities and public interest. The boom in traditional folk house in Japan reached its climax with the ten-volume photo book Traditional Japanese Houses (1959) by the architectural photographer Yukio Futakawa. This photo series, a collection of hundreds of photos of traditional folk house shot nationwide since the mid-1950s, rose to prominence after it was awarded the Mainichi Publication Culture Award. Futakawa was fascinated by the distinctive provincial styles of the traditional folk house in the isolated highlands and islands, which stoically withstood and adapted to rugged natural environments. The architect Itoh Deiji, who had accompanied Futakawa on nationwide site visits of traditional folk house, insisted that the traditional folk was an architecture that contained remnants of ‘the natural aesthetics of Japanese architecture, unlike modern architecture influenced by the West or Buddhist architecture with remnants of Chinese influence’, and that it was truly a breed of architecture that reflected the ‘quintessence of pure Japanese culture’.▼3 In Japanese architecture, the traditional folk house is considered the legacy of the dynamic hunter-gatherer society of the Jōmon (縄文) epoch, which emerged between BC 10,000 and BC 300, an era considered to be the primary source of Japanese culture.▼4

Choi Sunu·Kim Swoo Geun, ‘Korean Traditional House’, SPACE No. 64 (May 1972), pp. 18 ‒ 21.

Then what status does the traditional folk house hold in discussions of Korean tradition? Considering the notion that topping a house with giwa (Korean traditional roof tiles) was an easy method to secure a sense of Koreanness, what role does the traditional folk house play, and, in particular, what of the thatched-roof house—how are both realised in the collective imagination of that which is Korean? The fact that the thatched-roof house series was directed by Choi Sunu and Kim Swoo Geun, two main protagonists who guided the discourse concerning Korean tradition, has rendered this question all the more interesting. In stories of the history of Korean architecture, the meeting between Kim Swoo Geun and Choi Sunu is dealt with as a climactic moment. In this narrative, Kim Swoo Geun, plagued by disputes concerning Japanese style regarding the design of the Buyeo National Museum, met with the de facto ‘missionary’ of Korean aesthetics Choi Sunu, who finally opened his eyes to the virtues of the traditional, reborn as an architect who understood what was Koreanity. Choi Sunu in fact not only took on the role of personal mentor for Kim Swoo Geun, but was an active proponent in the discrouse of the traditional by participating as a key contributor since the establishment of SPACE. Although there is very little known about the content of their conversations and the specific details of their shared conception of Korean aesthetics, it is impossible to overlook the importance of their unique collaboration―epitomised by the thatched-roof house series. For Choi Sunu, the thatched-roof house is a metaphor that best reflects a view of nature where Koreans who live in harmony with nature and live by their means. He suggested that the true Korean spirit was embodied by private homes in which people conduct their everyday lives, rather than by impressive feats of architecture such as palaces, fortresses or temples. He also did not exclude comparisons with Japan and China. Korean houses were different from Japanese houses, which tended to adopt an artificial and neurotic aesthetic, and differed from Chinese houses which were exaggerated in character and extravagant; Korean houses advocated a natural beauty through a simple and mature style easily suited to one’s means.▼5 Here, ‘naturalness’ lies at the core of the Korean aesthetic asserted by Choi Sunu. Such a theoretical aesthetic was of course also reflected in the photos published in SPACE’s series. While photographs of Japanese traditional folk house commonly employed close ups and cropped shots to fit with the geometrical asceticism of modernism, the photographs in SPACE exhibited a naturalness with an intentional restraint regarding artificial expression of symmetry and geometrical lines. Moreover, rather than treating the buildings themselves as sculpted or independent ‘works of art’, the thatched-roof houses are featured as part of an alleyway which twists around the rear hill embracing the village, or as a backdrop for artefacts that bear the traces of agrarian life, such as jangdok (ceramic pots), jige (farmer’s carriers), sokuri (wicker baskets), and so on. Nevertheless, for Choi Sunu the traditional folk house was not seen as an architectural object, but as an integral part of nature, and as such he did not expect it to have any inherent formal value or aesthetic impact as aspired to by high-minded architecture. What he had selected as architecturally representative of the beauty of Korean houses was not the thatched-roof house of the minjung which ‘thrive autonomously like mushrooms’, but Yeongyeongdang, a stylish house of the elites exhibiting the distinguished taste of the sadaebu (scholar-officials). Moreover, Choi Sunu worried that if the distinguished hanok that remained within the Four Great Gates area were not properly preserved, later generations would come to conclude that the only unique aspect of Korean traditional architecture was the lowly rural thatched-roof house with its mudwalls.▼6

Kang Un-Koo, ‘Lyricism in Forms of Thatched Roof’, SPACE No. 109 (July 1976), pp. 34, 35, 38, 39.

Choi Sunu’s elitist approach to the traditional was succeeded by Kim Swoo Geun. Kim Swoo Geun held the thatched-roof house in high regard, valued as a human-scale house with a size, form and texture suited to the Korean climate, yet ultimately did not consider it to be a mainstay of Korean tradition that ought to be seriously considered as a legacy of Korean architectural form. The key component shaping Kim Swoo Geun’s architectural discourse that came into play was concern for the residential spaces of the dominant classes, in particular, the traditional study as a multi-use cultural space for male called sadaebu. This multi-functional space charged with munki (literary energy), was considered to be an asset of ‘The Third Space’, explored in the spatial theory of Kim Swoo Geun. This space was intended as a relaxed space of nature and harmony, a creative space of leisure and action, and an ‘Ultimate Space’ demanded by future society.▼7 In short, the significance of the traditional folk house (thatched-roof house) in the traditional discourse of Choi Sunu and Kim Swoo Geun is extremely limited. Nevertheless, for some, the thatched-roof house has minimally, yet enduringly continued to play its part in inspiring new thinking about what is Korean and what is traditional, and encouraging many to dream of an alternative life and society. From the early 1970s, the architectural historian Kim Hongsik, who conducted energetic research projects on traditional folk house dispersed across the nation as a member of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, stressed that the thatched- roof house was in itself the most minjok-like architecture made through materials and production methods unique to the nation’s people.▼8 Based on the maxims derived from the residential culture of the general public, from the influence of radical minjung discourse which rose to the fore in the 1980s, he asserted a ‘minjok architectural discourse’ which overcomes the social-class-based limits of the existing discourse on Koreanness and challenges the colonial attitudes that continue to pervade architectural culture. If the traditional folk house provided an outlet for Kim Hongsik to narrate Korean architectural history, placing the minjung at its centre, then it functioned as inspiration for Chung Guyon in forming an architectural practice robust enough to overcome the hold of Western modernism. Chung Guyon returned to Korea briefly in the 1970s when studying in France, and witnessed the widespread replacement of thatched-roofs of agrarian homes with flimsy industrial materials, and would later remember this as a sort of original experience as an architect.▼9 His lifetime dedication to ‘clay/ earth architecture’ was elected not so much as a traditional roof material for thatched- roof house, but as an attempt to take note of the materials and technologies used to build walls and to modernise them. Here, ‘clay/earth architecture’ was not representative of an impoverished past that must be surmounted, but indicative of a minjung-oriented plentiful future for architecture armed with durability, affordability and environmental friendliness. (written by Cho Hyunjung / edited by Bang Yukyung)

-

1 The photographer (Kim Jinwhan) is named in SPACE No. 64 (May 1972), and the names of the surveyors (Kim Namhyun and two others) also appear in SPACE No. 67 (Aug. 1972).

2 Choi Sunu·Kim Swoo Geun, ‘Korean Traditional House’, SPACE No. 63 (Apr. 1972), p. 18.

3 Futagawa Yukio, Itō teiji, Japanese Traditional Folk Houses, Tokyo: A.D.A.Edita, 1980 (first edition; 1959), p. 10.

4 Shirai Seiichi,‘Things about Jōmon: About the Mansion, Egawashi-Kyu-Nirayamakan’, Shinkenchiku (1956.8), pp. 4 ‒ 7.

5 Choi Sunu, Leaning on Muryangsujeon Hall Baeheullim pillar, Hakgojae, 2002, p. 15.

6 Choi Sunu, Complete works of Choi Sunu 2, Hakgojae, 1992, p. 407.

7 Kim Swoo Geun, ‘Negativism in Architecture ’, Narrower the better is the good road, wider the better is the bad road, SPACE Publishers, 1992, pp. 240 ‒ 248.

8 Kim Hongsik, Thatched-Roof House, Youlhwadang Publishers, 1991, p. 207.

9 Chung Guyon, People, Architecture, City, Hyunsil Munwha, 2008, pp. 70 ‒ 88.

and received a doctorate from the University of Southern California with a thesis on Japanese architecture history. She is interested in the interface between architecture and art, and the relationship between Korean and Japanese architecture. Her books include Postwar Japanese Architecture, which summarises the flow in modern Japanese architecture, and co-authored the following; The Specter of the National Avant-garde, Kim Chung-up Dialogue, Pavilion: Filling A City with Emotions, The Experiments of Architopia, and Eyes of the Era. She also co-translated Art History After 1900.