The cover of SPACE No. 216 (June 1985)

There was a time when notions of the ‘modern’ aroused certain aspirations and anxieties. It gestured towards frontrunners assumed to have already achieved a set goal, but prompted anxiety in relation to the scale of the desire and its ambitions since they typically could not be easily met or satisfied. The perception of temporal and spatial distance in modernity throughout our imagination and belief systems induces the two emotions. Modern is a word that not only represents a historical period but also questions classifications and conditions. In the mid-twentieth century, Korean architects were eager to reach into the remote core of modernism, and so had to face unavoidable questions; ‘Are you and your architecture modern enough?’, ‘Do you know the definition of modernism?’, and even ‘Do you believe in Modernism?’

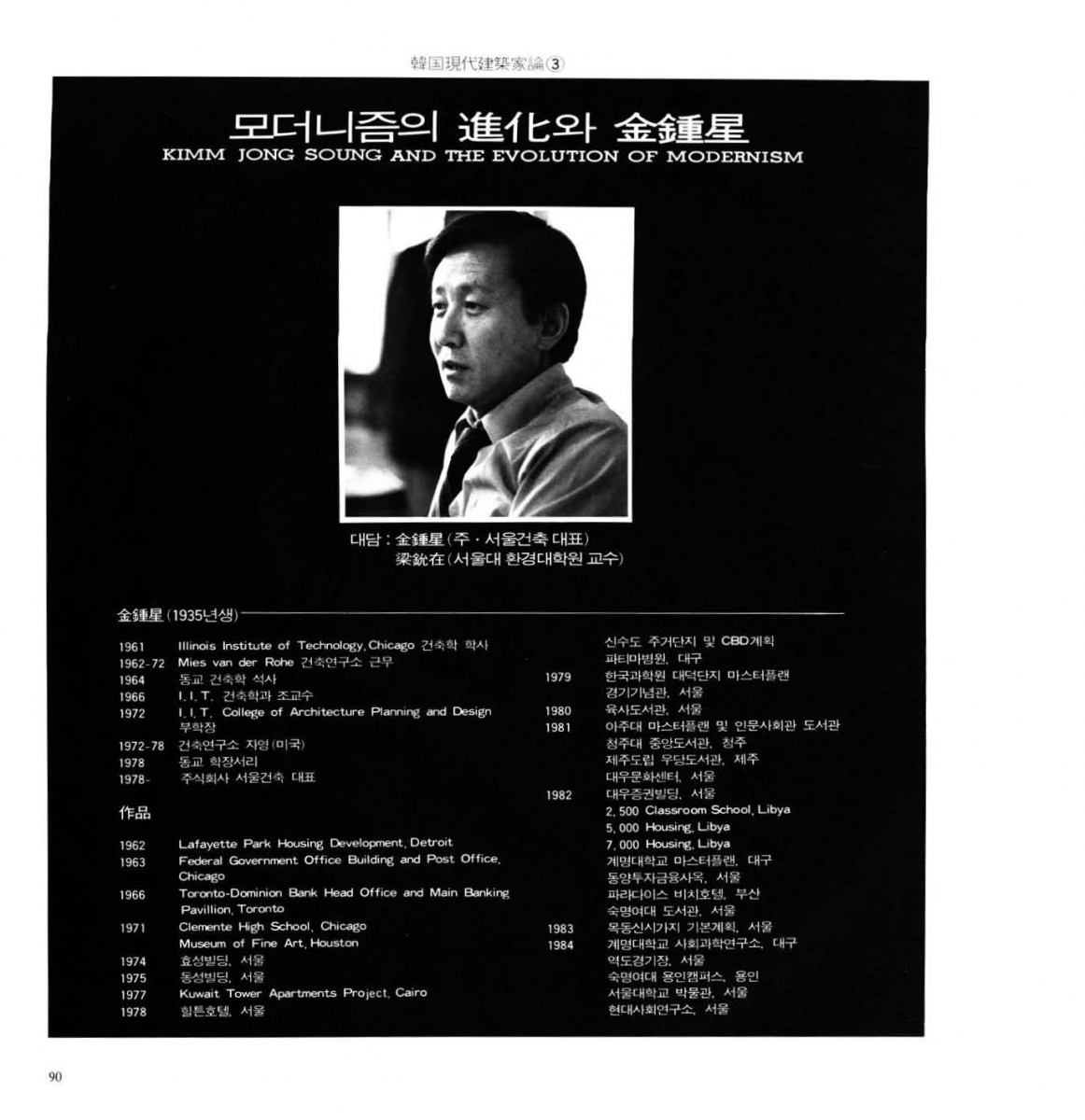

The first page of ‘Kimm Jong-soung and the Evolution of Modernism’, SPACE No. 216, p. 90.

Few architects were able to answer this question with certainty. Kimm Jongsoung must be one of the few who could speak about and practice modern architecture with a firm resolve and clarity of thought. He came closer to the essence of modern architecture than any other Korean architect at the time. Although Park Chunmyung and Khang Byongkee studied in Tange Kenzo’s laboratory at the University of Tokyo, and Kim Chungup worked at Le Corbusierʼs atelier, they cannot be compared to the relationship that Kimm Jong-soung established with Mies van der Rohe as a student, office staff member, and junior professor. He is the only person who deserves to be recognised as a successor to this essence while also remaining a modern mythical figure for a long time. Kimm Jong-soung, who went to study abroad at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chicago in 1956 and returned to Korea in 1978 after working in Miesʼs office and as the dean of IIT, was the embodiment of modern architecture.

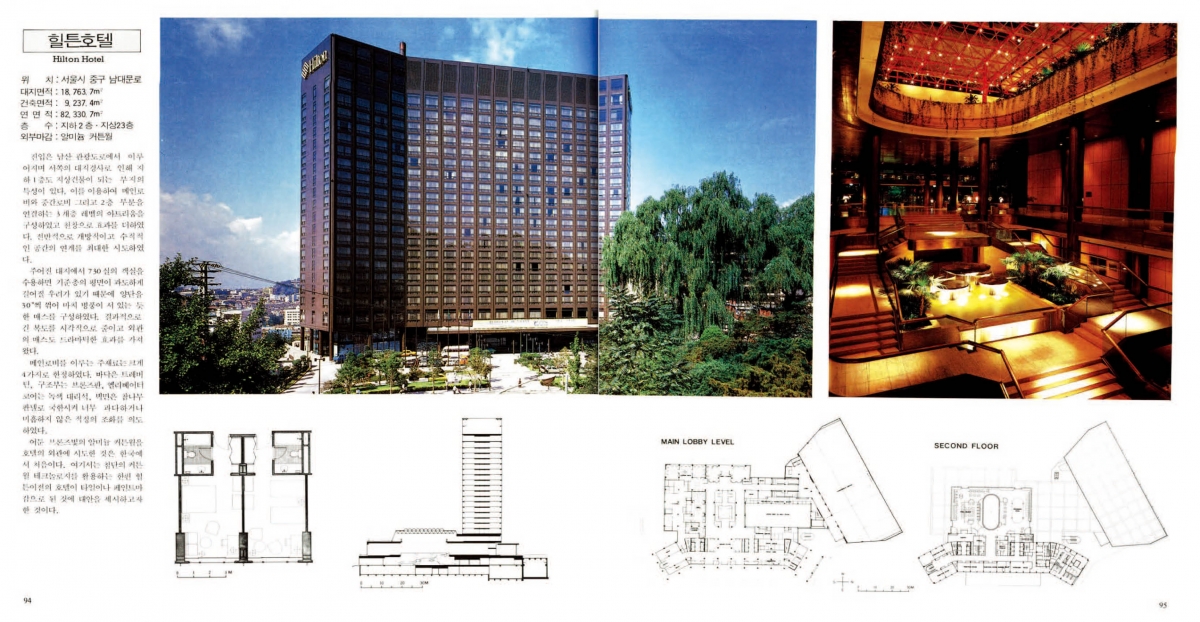

SPACE No. 216, pp. 94 – 97.

In 1985, when voices were raised to say that one could escape from the anxiety and aspiration resulting from modernity (or pretend not to know) were gathered under the name of postmodernism, there was no person more suitable than Kimm Jong-soung to call back modernism. SPACE No. 216 (June 1985) presented a series of special feature, ‘Kimm Jong-soung and the Evolution of Modernism’. It was the third article in the ‘Contemporary Korean Architects’ series after ‘Architectural Craftman Aum Dukmoon’ published in March and ‘Park Chunmyung, Architecture with Reasonableness’ in May. The special features consisted of a conversation between Yang Yunjae, a professor at Seoul National University Graduate School of Environmental Studies and Kimm Jongsoung, Yang Yunjaeʼs postscript of interview, ‘Rationalism in Irrationality’, and the architect Son Dooho’s essay ‘Close-up of Professor Kimm Jong-soung’. The dialogue begins with the story of how Kimm Jongsoung chose IIT to study under Mies, and focuses on the development of his major contributions to architecture up to 1985. Since then, this narrative, repeated in several media interviews and in Conversation with Kimm Jong-soung (2018), has become popular myth in Korean modern architecture.

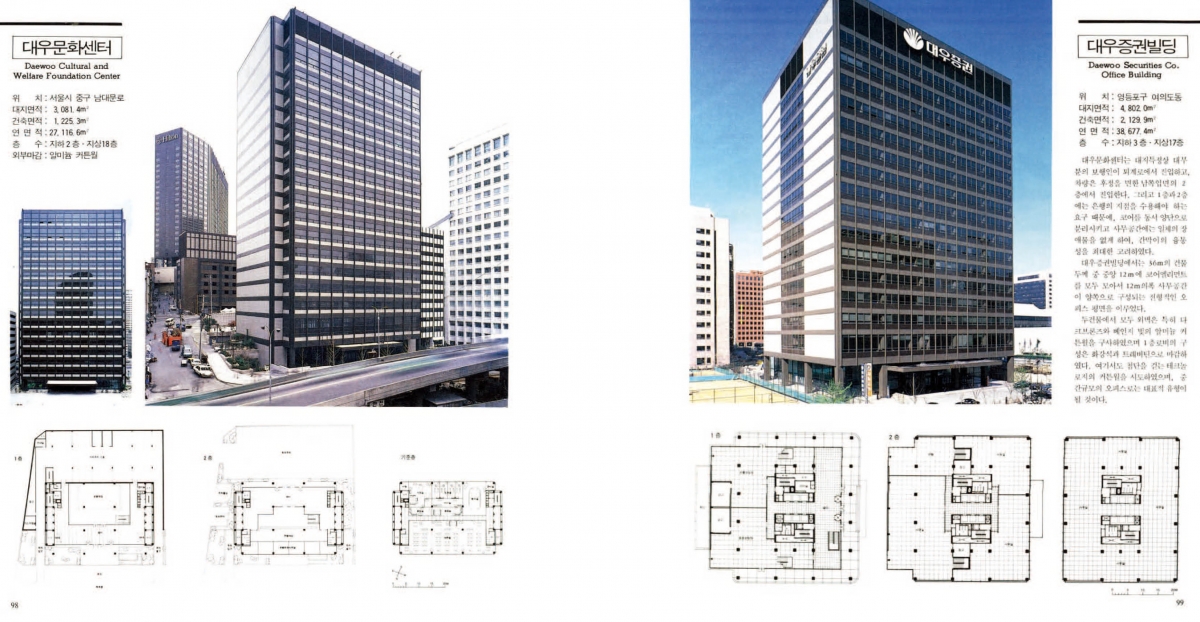

SPACE No. 216, pp. 98 ‒ 99, 91 ‒ 92.

In his postscript to the interview, Yang Yunjae expressed the hope that Kimm Jong-soungʼs return to Korea (1978) and his ensuing career would open a ʻnew chapterʼ in Korean contemporary architecture.▼1 Surprisingly, he compared the period before and after the French Revolution and that of the May 16 Revolution; just as symbolist architecture was demanded right after the French Revolution, symbolic and aesthetic meanings were emphasised right after May 16. Although he doesn’t mention specific projects, it is not difficult to guess that he likened this to the large national projects of the 1960s and 1970s which were built to stress the Korean potential for French architecture in the time of the French Revolution, such as Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and Jean Jacques Lequeu. He meant ʻarchitecture parlanteʼ. Contrary to this tendency, Yang Yunjae diagnosed Kimm Jong-soungʼs architectural approach as one which pays attention to the rationality of architecture itself, resembling Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durandʼs rationalism. He explained that Durand, who thought that ‘aesthetic value in architecture is naturally revealed in rational structure and function’ had a ʻdeep influence on Auguste Perret and Mies van der Rohe’. ▼2 Looking to the end of age, one tries to read meaning in architecture. As the advent of an era that pursues rational structure and function, Yang Yunjae saw that Kimm could lead this new trend. It is interesting to note that this challenge was seen as a departure from Japanese influences on Korean architecture. In fact, architects in charge of national projects in the 1960s and 1970s, such as Park Chunmyung, Lee Hitai, Kim Chung-up, and Kim Soo Geun, were all under Japanese influence. This trend began to be reorganised around the return of architects who studied in the States, and Yang understood Kimm Jong-soung to be spearheading such practices and attitudes. In writing of his personal impressions about Kimm, Son Dooho explains why he is always referred to as ‘professor’: an excellent understanding of details and an extraordinary sense of proportion and balance throughout the episodes.

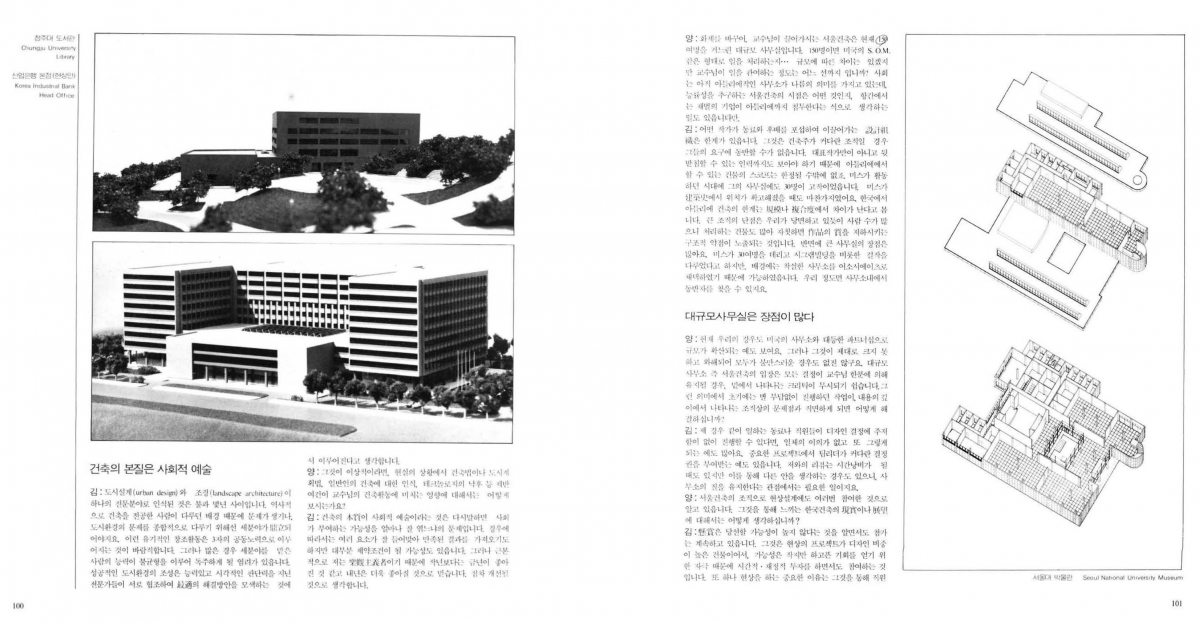

SPACE No. 216, pp. 100 ‒ 103.

Both Yang and Son wrapped up the article with the hope that Kimm would continue to produce great works by committing his time to his major projects. In the mid-1980s, SAC International was already a large architectural firm with hundreds of employees. At this point, it is useful to consider the areas left unmentioned in Kimm’s work and in most of his architectural writings.▼3 We should recognise the large architectural firms which increased business scale in earnest during the late 1970s and mid-1980s, and their projects as our object of historical study. For this, we must examine the background to the accumulation of capital in the Korean economy, the expansion of subsidiaries of conglomerates, the reorganisation from government-led monumental projects to large construction projects of companies, and the emergence of architectural firms that were as good as the close affiliates of conglomerates. Recently, it became known that the Hilton Hotel with its outstanding degree of completion, one of his masterpieces that paved the way for him to quit as dean of IIT and to return to Korea, was to be demolished for redevelopment. This also prompted the necessity for more developed evaluation of Kimm and his life, work and legacy, discussion of which should also be widened from exploration of the significance of an individual to our society. The buildings in the 1960s and 1970s by Yang, informed by the school known as ‘symbolism’, belong to a breed of architectural projects that aim to establish a stronger sense of ‘identity’. Architecture was a means of expressing a unique identity that could serve to differentiate one country or culture from another, even if it was in terms of imaginative powers. The methods to realise this were largely focused on reinforced concrete, which is easy to form. After World War II, concrete was used to express the warring ideologies of capitalism and socialism and the identity of community regardless of regional context, from Asia, to America, to Europe. Some of these stylings with concrete are now characterized under schools such as Brutalism or Socialist Modernism. Miesian architecture also aimed for universality. Strict proportions and modular systems were devices that gave order to nature and kept pace with standardised industrial production. ▼4 It was a system that transcended place and programme. Although a guiding principle was to coordinate with programmes such as offices, apartments, hotels and art museums, alongside consideration of regions and places, the Miesian space develops according to its own logic. Who would question a sense of place in Mies’s buildings? This architectural universality assumes universality of modern world, or more precisely, of the capitalist system. Without the steel frame and curtain wall production system, a Miesian space cannot be implemented. If we accept that Miesʼs architecture is uniform and anonymous, it is no coincidence that his projects were confined to the United States after World War II. The uniformity and anonymity of Miesian architecture cannot be considered as distinct from the universality of capital. Kimm also recalls that he had to figure out what could be done in Korea where there was no infrastructure for the mass production of curtain walls when he designed Tongsung Building and Hyosung Building in the mid-1970s.▼5 It is also no accident that conglomerates began to establish affiliate architectural firms to carry out their own construction projects in the late 1970s after the Korean economy underwent heavy industrialisation.▼6

Miesian Modernism after World War II is emblematic of corporate modernism. Can this approach be applied to Kimm Jong-soung and SAC International? Since he returned to Korea and established his architectural firm in 1978, he has worked on more than 1000 projects.▼7 How have these many works affected our understanding of Korean corporate modernism? If it hasn’t, then why not? This line of questioning continues. To what extent should we expand upon our evaluation of Kimm Jong-soungʼs heritage? Can we assume that only the projects to which he paid affection and attention are those among his works, and the rest to SAC International? This question renews. a debate about the individuality of an architect and the necessary anonymity of large organisations. Conflict between these two parties usually focus on how to secure an individual architect’s prestige within the realm of the organisation. For example, the key to the uniqueness of Park Seonghong’s role, architect of the National Museum of Korea, was that it could be positioned within Junglim Architecture. On the other hand, Kimm Jong-soungʼs fame is not in conflict with SAC International. If the relationship between him and his firm is exceptional, how should we interpret the typicality of this organisation? Can we simply regard that a few outstanding masterpieces and many ordinary works correspond to him and SAC International respectively? The relationship between individual architects and their firms is directly related to the question of whether large architectural firms can survive after retirement of their founder. How should we perceive the legacy of Kimm Jong-soung and SAC International after him? This is not an easy question to answer, but we should face it in order not to perpetuate any myth-making narratives. The task of criticism and history is freighted with challenges for us all. (written by Park Junghyun / edited by Kim Jeoungeun)

In our next issue Suh Jaewon will cover the Residence of Mr. Kang by Yoo Kerl which featured in SPACE No. 41 (Apr. 1970).

------

1 Yang Yunjae, ‘Rationalism in Irrationality’, SPACE No. 216 (June 1985), p. 102.

2 Ibid, p. 103.

3 After 37 years, documentation of Kimm Jong-soungʼs personal data has been presented faithfully through exhibitions and the archives of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, as well as publication of his theoretical writings and interviews. The means of understanding Kimm Jong-soung are more robust and comprehensive than many other contemporary architects.

4 Jung Inha notes that Miesʼs module gives order, is relevant to standardised industrial production that maximises efficiency, and produces a unique mechanical aesthetic. Jung Inha, Tectonic Logic and

Spatial Imagination, SpaceTime, 2003, pp. 98 ‒ 99.

5 Conversation between Yang Yunjae and Kimm Jong-soung, SPACE No. 216, p. 96.

6 Samoo Architects & Engineers (Samsung) was established in 1976, Dongwoo Architects (Daewoo), the predecessor of SAC International in 1977, and Chang-jo Architects (Lucky Goldstar) in 1984.

7 Jung Inha, op.cit., p. 94.