SPACE June 2022 (No. 655)

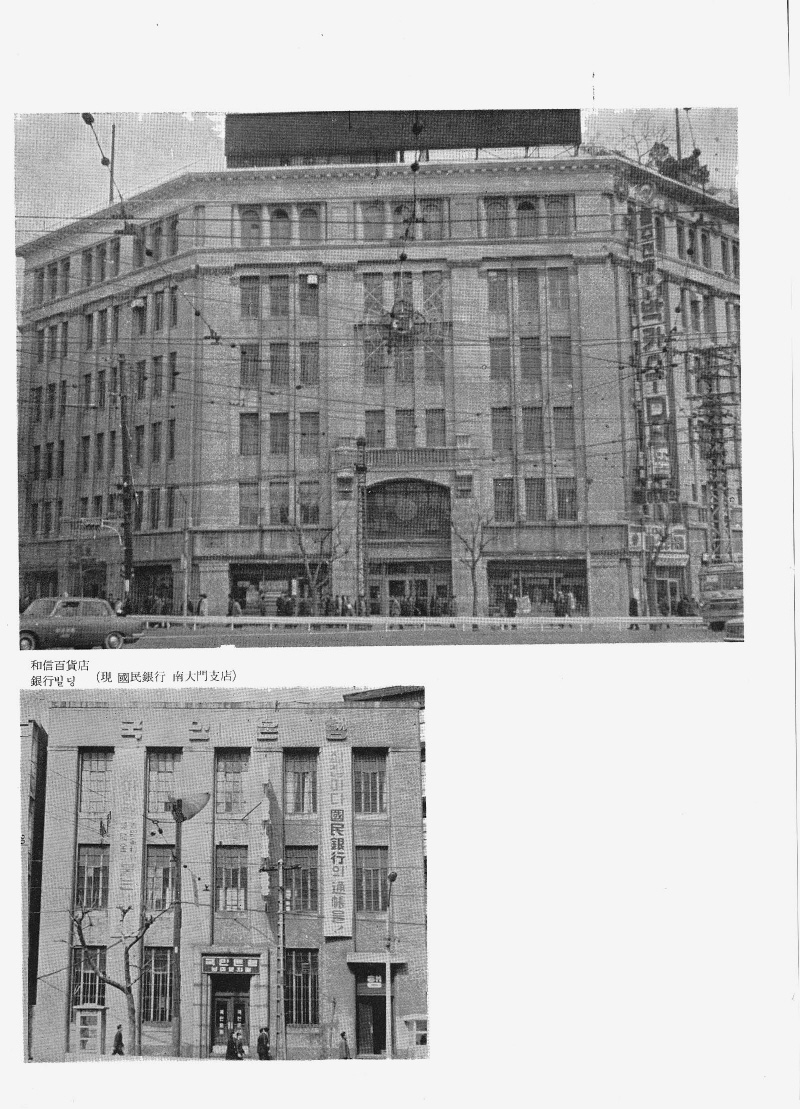

The ‘Editorial Postscript’ in the first issue of SPACE (Nov. 1966) addresses a number of articles that were not published, but which were originally planned for publication. It was due to a lack of space and the unexpected incomplete state of some of the manuscripts. Among them was a ‘Profile of Mr. Park Kilyong’.▼1 He must be the man we know of: Park Kilyong (1898 – 1943), a representative figure of the first generation of Korean architects. As is now well known, he studied architecture at Gyeongseong Technical College during the Japanese colonial era, worked at the Government-General of Chosun, opened ‘Park Kilyong Architectural Office’ in 1932, and designed diverse modern buildings, including the famous Hwasin Department Store (1937) in Jongno, Seoul. More than this, he took the lead in improving traditional Korean houses and the floor heating ondol, remained enthusiastic about various social activities, and nurtured many Korean architects at that time. It was natural for SPACE to introduce this breed of man, Park Kilyong, in the first issue. That is because, by tracing the genealogies of senior architects, the next generation of architects would be able to scrutinise their current position and set new coordinates for the future. Looking back at this time, it was rather fortunate that his article was postponed. It would not have been appropriate to cover a person like Park Kilyong with merely a simple profile although the honour to be selected for the first ‘Architect Special Feature’ was given to Kim Chung-up in SPACE No. 5 (Mar. 1967). Park Kilyong was covered, a month later than Kim Chung-up, in SPACE No. 6 (Apr. 1967). It was entitled ‘Architect Park Kilyong: Commemorating the 24th Anniversary of His Death’. This issue had the added significance of commemorating a profoundly influential figure who passed away in the same month 24 years ago.

The first page of ‘Architect Park Kilyong: Commemorating the 24th Anniversary of His Death’, SPACE No. 6, p. 6.

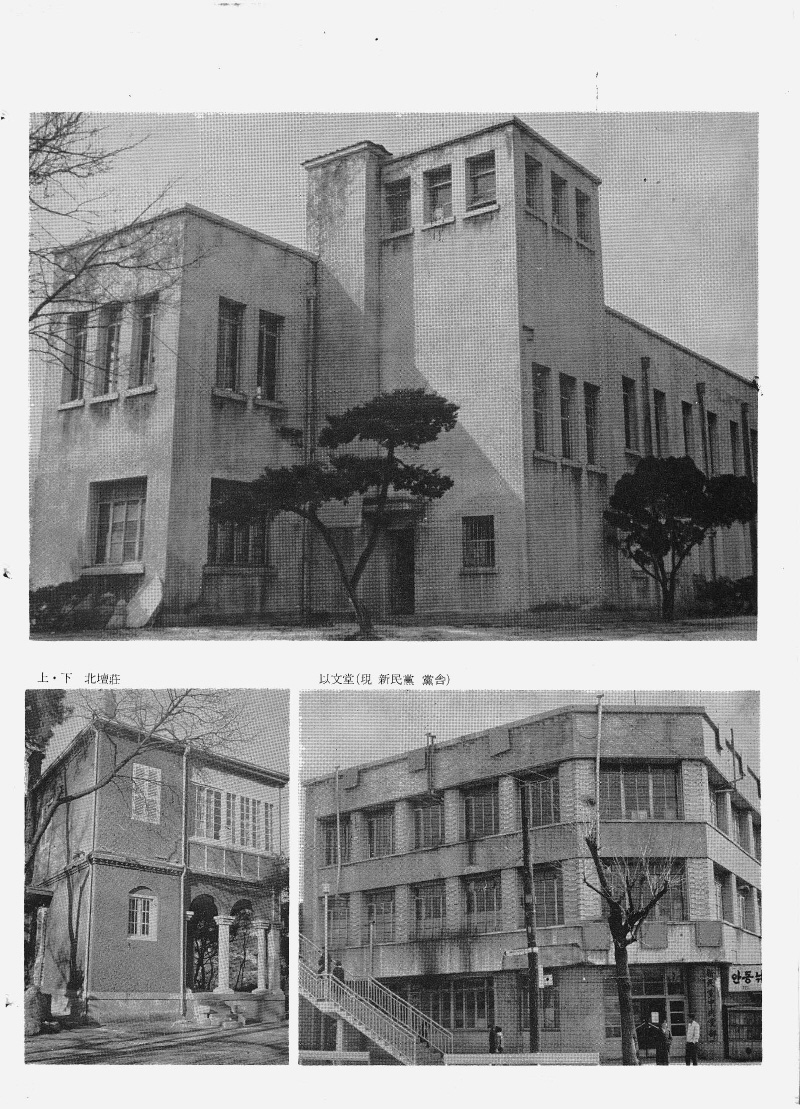

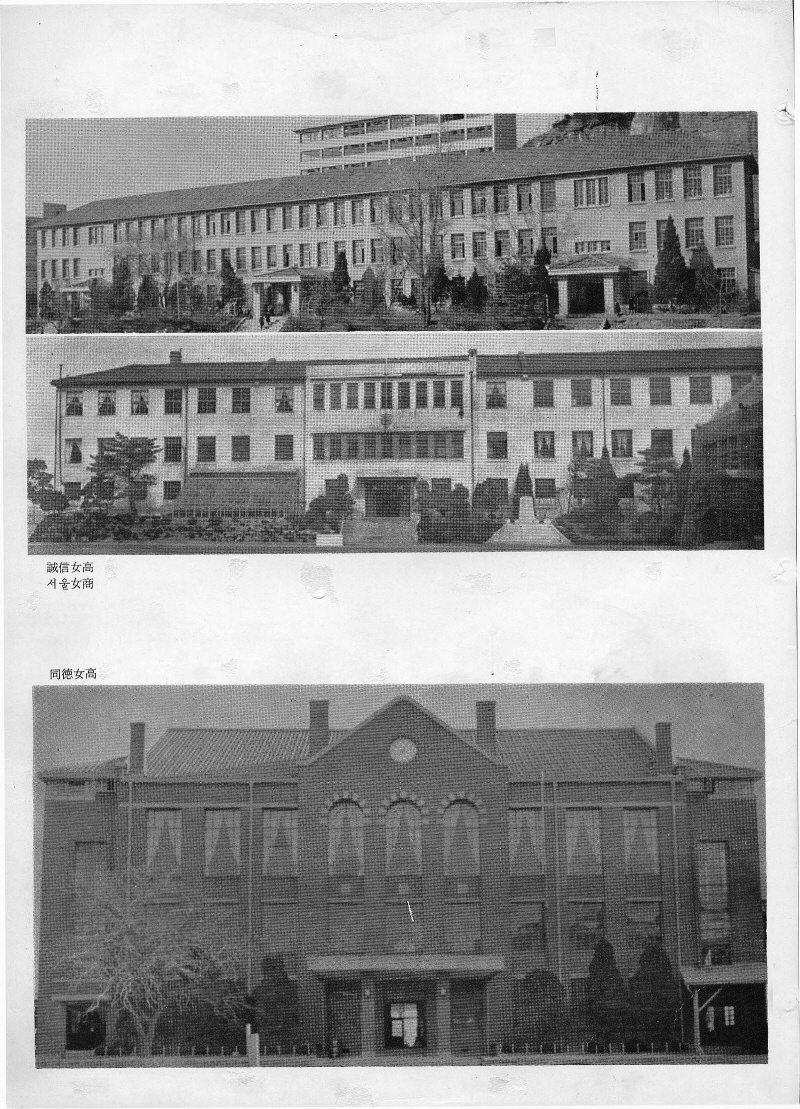

The section of this special feature is placed immediately after the table of contents and Limb Eung Sik’s ‘Space’ photo. The profile photo of Park Kilyong, covering the entire page, along with the next page’s lament written by his son Park Yonggu 24 years ago, serves as its opening, which is followed by four pages illustrating his designed buildings. It is Yoon Iljoo’s text in the next, entitled ‘Architect and Society: The Meaning of Life and Achievements of Mr. Park Kilyong’, which can be viewed as the main article of this special feature. This was followed by ‘Memoirs’ written by ten acquaintances of Park Kilyong, and ‘List of Books and Posthumous Writings’ compiled alongside his biographical profile. Subsequently, three articles from the ‘Posthumous Writings’ were added like appendices. They are: ‘A House Design for Low-Income Families (Korean Style)’ (unpublished), ‘Miscellaneous Observations on Chosun Houses’ (published),▼2 and ‘Regarding the Trend of Building Houses in New Residential Districts’ (unpublished). There is one thing we should remember here: right after Park Kilyong passed away, Chosun and Architecture, the Japanese architectural magazine published in Korea at that time, lamented his death with ‘Condolatory Writings’ in the issue of May 1943. Along with his photo, biographical profile, and illustrations of his designed buildings, the magazine published condolatory addresses by ten contributors. It seems that SPACE would have referred to this to develop the format and content of their special feature on Park Kilyong (the aforementioned lament by Park Yonggu is a Korean translation of the Japanese writing from Chosun and Architecture, and Yoon Iljoo also actively draws information from this magazine). Here, by chance, we come to realise that there have not been any works that highlight this important figure Park Kilyong over a quarter of a century. Perhaps we could not afford to do so, after living through the turbulent years of Liberation and the Korean War. Even Yoon Iljoo, who was in charge of the main article, confessed that he ‘had known almost nothing’ about Park Kilyong ‘other than recognising his role as a great senior in the architectural world and the designer of the Hwashin Department Store’, and added that he was able to write about him by virtue of the materials that SPACE had collected when conducting preliminary research. This context contrasts with the special feature on Kim Chung-up a month ago, which even included much more active reviews entitled ‘Artist Kim Chung-up’ and ‘On Kim Chung-up’s Works’, in addition to more abundant illustrations for each architectural work.

SPACE No. 6, p. 8.

However, such a regret renders the special feature on Park Kilyong in SPACE No. 6 even more compelling and necessary. This was the starting point for collating materials on Park Kilyong, and it could be suggested that research on the first generation of Korean architects started from here. Despite several imperfections,▼3 this special feature allows us to register the voices of those who worked beside him, shows samples of writings that encompass his architectural concept, and offers general commentaries on his position in architectural history in Korea. Let’s first take a look at Yoon Iljoo’s article. As its title suggests, he discusses the relationship between ‘architect and society’ from the beginning, revealing his intention to ‘examine the social aspects of the 1920s and 1930s to highlight his position in architectural history’. His interest, in the end, lay with how much Park Kilyong maintained a ‘national pride’ and expressed it architecturally, in the midst of social conditions behind the Japanese colonial era. Yoon Iljoo was initially concerned about the ‘pro-Japanese elements’ that might be discovered in him, but relieved to assure that he had ‘a clear position and claim as a Korean’. This was based on his insights and efforts to improve traditional Korean houses, his publication of the Japanese-Korean magazine entitled Architecture Chosun, and the writing of a Korean architectural glossary whose usage was unclear at that time. He also stressed that, in the aforementioned issue of Chosun and Architecture, only Park Kilyong and Park Yonggu appeared under names which were not changed to Japanese styles.▼4 Regarding Park’s architectural concept, Yoon highlighted his argument that the Japanese house style should also be avoided to improve traditional Korean houses. There has been a recent rise in criticism of Park Kilyong, that is, criticism of the ‘limitations and contradictions of technocrat in the colonial era’, implied in his personal history: right before his college graduation he did not participate in the March 1st Movement in which many Korean students at Gyeongseong Technical College participated, and this coupled with his work experience at the end of Japanese colonisation.▼5 Yet in the 1960s, these do not seem like the problems to be addressed so easily. Also, the first narrative of Park Kilyong, which would be the subject of such criticism, had not yet been established. Perhaps the potentials of ‘functionalism’ and ‘modernity’ in the writings and works of Park Kilyong, which were discovered by Yoon Iljoo,▼6 are a stepping-stone to the forthcoming narrative of Park Kilyong. However, just as Park Kilyong’s career retains the limitations of the times as well as having great significance, so too does Yoon Iljoo’s narrative. His surprisingly clear reading of the relationship between the ‘architect and society’ was rendered somewhat dull when discussing Park Kilyong. The criteria of evaluation that he presented at the outset were ‘how far the architect exhibited an avant-gardism going over social conditions’ and ‘how thoroughly he reflected this in contemporary art’.

SPACE No. 6, p. 9.

Meanwhile, the ten memoirs convey Park Kilyong’s tendency to lead, wide network, personality respected even by the Japanese, and daily life at the office, in a multifaceted manner. Among them, Kim Hansup’s memoir is as comprehensive as Yoon Iljoo’s main article. It was based on his experience of working under Park Kilyong for 13 months as the last member of Park Kilyong Architectural Office. Kim Hansup, who had assisted Park Kilyong’s design and research during the time, tried periodisation of Park Kilyong’s research on houses. According to him, Park was immersed in ‘surveying traditional houses’ in his early years, ‘improving traditional houses’ in his middle age, and ‘researching small-scale houses (low-income houses)’ in his later years. In fact, Park’s interest in small-scale houses was already expressed in his early publications,▼7 but it may be a minor issue for Kim Hansup’s big picture. Furthermore, he even went on to remark that Park Kilyong suggested a path for the younger generation by ‘pursuing national and regional architectural styles while emphasising rationality and purposefulness’ in the midst of a global trend for a more international architectural style. Also, his writing includes some noteworthy stories, such as: Park Kilyong criticised the ‘developer’s housing’ in Anam-dong; and he proposed a fourcheok-module around 1935 to promote prefabrication for the mass production of housing. The former reveals Park’s critical stance on the so-called ‘urbantype hanok,’ which we prize highly today, and the latter reveals Kim’s possible misunderstanding over the idea because Park asserted the eight-cheok standard in his On the Improvement of Traditional Korean Houses (Vol. 1, 1933) and others. Aside from Kim Hansup, it is also worth paying attention to Kim Haerim who wrote that Park Kilyong had possessed a profound interest in Frank Llyod Wright, as well as Jeon Changil who pointed out ‘irrational and contradictory part’ inside the Hwashin Department Store. The much more indispensable memoir is the recollections of Choi Kwangpil: he describes how the Park Kilyong Architectural Office building in Gongpyeong-dong was built. According to him, the original office occupied a space of ten-pyeong on the second floor of a wooden building in Gwanhun-dong, but the space gradually became insufficient, and so after three years, the new building was built in Gongpyeong-dong by virtue of the help by acquaintances. The new building consisted of living space on the first floor and an office on the second floor with an employee office space of fifteen-pyeong, as well as an exclusive room of five-to-six-pyeong for Park Kilyong with a reception area. Because it is sometimes mentioned that Park Kilyong opened an office in Gongpyeong-dong from the beginning, this writing serves as a correction to that. Furthermore, it reminds us of Kim Swoo Geun, who had his own space after erecting the Space Group of Korea Building.▼8 These two architects, representatives of each generation, are similar in that they both led various persons into their own spaces and actively interacted with them, even in the fact that their relationship with society is at times criticised from the present point of view.

SPACE No. 6, p. 10.

Lastly, let’s discuss the posthumous articles included in the special feature. The publication of these three pieces is meaningful today, even when research on Park Kilyong has progressed to some extent.▼9 It is not only because the two unpublished manuscripts were introduced, but also because, although the SPACE editorial team’s reasons for selecting these three were not stated, there seems to be an internal logic in the selection. When these articles are placed together, the contradiction between his eclectic and functionalistic stances is often found on the one hand; but on the other, his architectural concept (concept on houses) can also be identified comprehensively. If ‘A House Design for Low-Income Families (Korean Style)’ shows us his specific theory for proposing a small-scale house based on a centralised floor plan, middle corridor, basement ondol system, and 8-cheok column-to-column unit,▼10 ‘Miscellaneous Observations on Chosun Houses’ manifests his general theory that expresses the ‘fundamental idea of improving houses’, criticising Korean houses at that time. In addition, ‘Regarding the Trend of Building Houses in New Residential Districts’ can be seen as a housing theory on an urban planning scale that goes beyond the scope of individual houses, and it criticises the architectural trends in new residential districts (Donam, Anam, Sinseol) that only seek profit. An interesting thing to note in this article is that he describes the English Garden City as a new standard. From this perspective, it seems that there is much more to research Park Kilyong’s architecture in the future, as much as what has been studied so far. Whether in the illustrations of his buildings or in the list of his writings published by SPACE, are further explorations not always welcome?

In our next issue Suh Jaewon will cover the Residence for OH by Kong Illkon which featured in SPACE No. 56 (July 1971).

-----

1 See ‘Re-visit SPACE’ 13 in SPACE, No. 650 (Jan. 2022).

2 This article was published in Chosun and Architecture (Apr. 1941), but it seems to have been included here because of its significance as a handwritten manuscript (21 Mar. 1941). There are major and minor differences between the Japanese version published in Chosun and Architecture and the Korean version published in SPACE. Most notable is the fact that many sentences in the last paragraphs of the former are omitted in the latter.

3 For example, there is no list of his designed buildings in this special feature while the ‘List of Books and Posthumous Writings’ was included. The omission of the building list is hardly covered by the rather arbitrarily selected ten photographs of his buildings in the illustration pages.

4 However, the writing of Yoo Sangha also appeared under his Korean name. Meanwhile, Kim Seyeon who succeeded Park Kilyong Architectural Office immediately placed an advertisement in the same issue of Chosun and Architecture, in which he used his Japanese-style name.

5 Hamm Seongho, ‘Architecture in Solidarity – Social Practices of Architecture and Architects,’ Architectural Critics Association, No. 6 (Jun. 2016), pp. 50-63. Come to think of it, Kasai Shigeo even described Park Kilyong as ‘a person of Naeseonilche (Japan and Korea Are One)’ in his condolatory address published in the issue of Chosun and Architecture.

6 He identifies functionalism in Park Kilyong’s ‘Miscellaneous Observations on Chosun Houses’ (especially from the sentence stating ‘without being captured by existing notions, we should start again towards a new direction that life itself expresses’) and modernity in some designs such as ‘Gyeongseong Medical School Hospital (Military Hospital in the Capital)’. However, it is necessary to verify whether Park Kilyong was the designer of the Gyeongseong Medical School Hospital, which was recently reborn as part of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul.

7 See early examples including ‘Reflections on Improving Our Houses (24) – (25)’ (Chosun Ilbo, 9-10 Nov. 1926); ‘One Exemplary Design for An Improved Small-Scale House’ (Chosun, Oct. 1928).

8 See ‘Re-visit SPACE’ 1 in SPACE, No. 638 (Jan. 2021).

9 Fuller research on him can be considered to have started with Choie Soonai’s master’s thesis submitted to Hongik University in 1981, entitled A Study of the life and architecture of Park Kill Rong. Various research has been carried out on his architecture and his house-improvement theory.

10 Although it is unknown when Park wrote this article, the basic concept behind this house is consistent with what was argued in On the Improvement of Traditional Korean Houses (Vol. 1, 1933; Vol. 2, 1937).