SPACE August 2022 (No. 657)

SPACE played a significant role in the production and reception of Korean art in the latter half of the twentieth century. Established as an arts magazine in 1966, it continued to influence artistic trends for more than three decades before adjusting its focus in the early 2000s to attend solely to architecture, marking a transitional period. However, the golden age of SPACE in terms of its relationship to Korean art stretches from immediately following its founding to the launch of various art magazines – Gyeganmisul (1976), for example – in the late 1970s. At that time, against the backdrop of increased urbanisation and industrialisation, national institutions and commercial art galleries such as the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (1969), Myeongdong Gallery (1970), and Gallery Hyundai (1970) were all established. Accordingly, enthusiasts, audiences, and collectors emerged, and the demand for information, education, and discourse steadily increased. SPACE was the only platform which addressed the pending problems and issues in European, American, Japanese, and Korean art, in a timely fashion but with requisite depth. Moreover, since this was before the Korean art market began to expand, special features and reviews related to art were able to continue in-depth, remaining distant from taking account of commercial aspects or the interests of advertisers. As the only art magazine published by an architect, artists were exposed to an agenda and to approaching the challenges of architecture and the city. It piqued interest in the point at which art and architecture intersect, which leads from mural paintings and three-dimensional artworks to ‘outdoor sculptures’, ‘environmental art’, and ‘public art’. However, SPACE played a much wider ranging and more profound role in Korean art. SPACE triggered controversy by addressing the most pressing issues in the field of Korean art from the perspective of governing concepts such as tradition, conception, abstraction, technology, folk paintings, ethnicity, and individuals or community. It is not a coincidence that two artists, Oh Kwangsoo (1967 – 1973) and Park Yongsook (1973 – 1978), worked at SPACE as the editor-in-chief and as an editor at the time at which they were at the peak of exerting their influence. Their plans and proposals made SPACE a dynamic force in the production and acceptance of Korean art, in some cases establishing the key concerns and directions of Korean art.

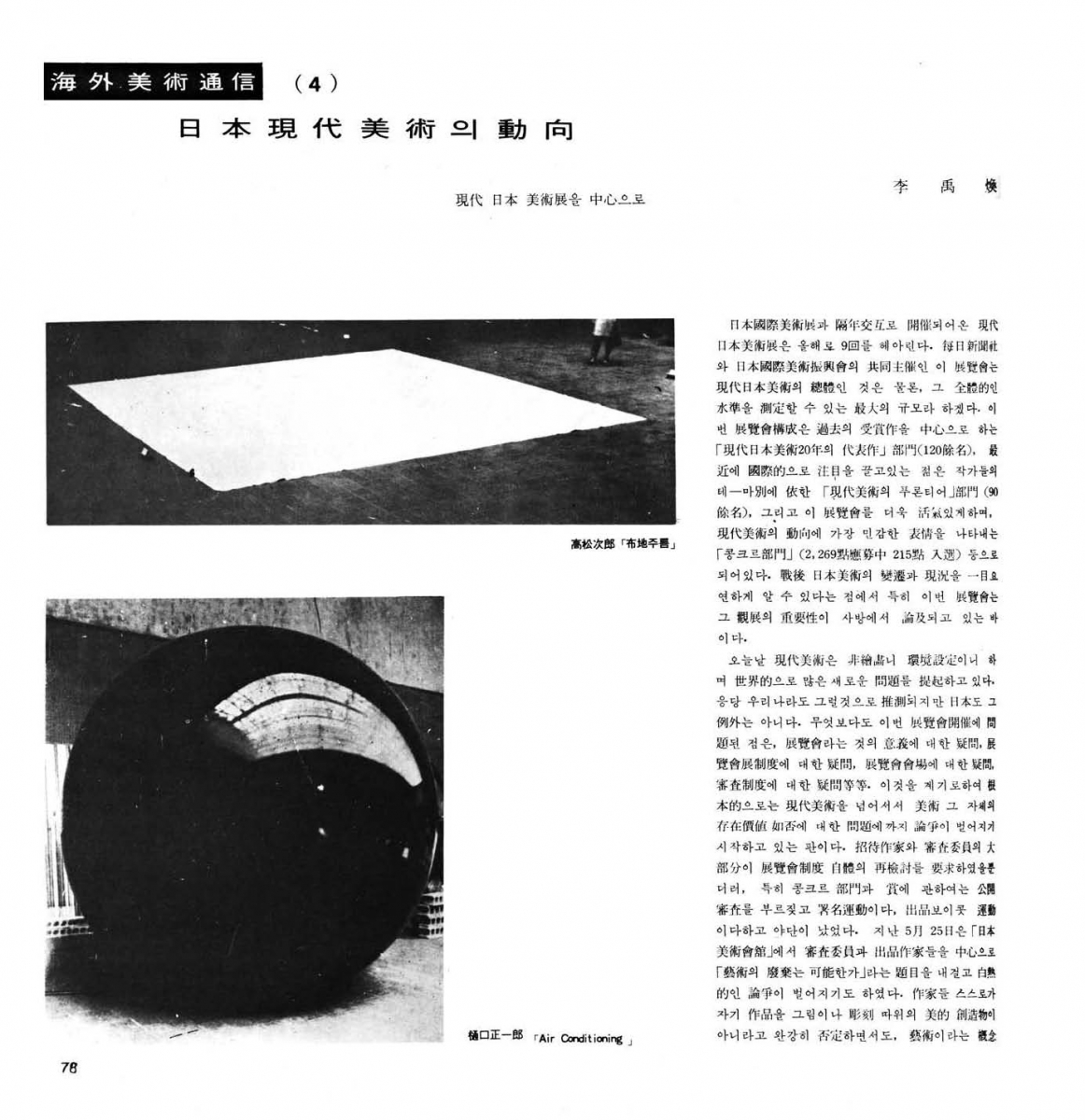

SPACE No. 32, p. 78.

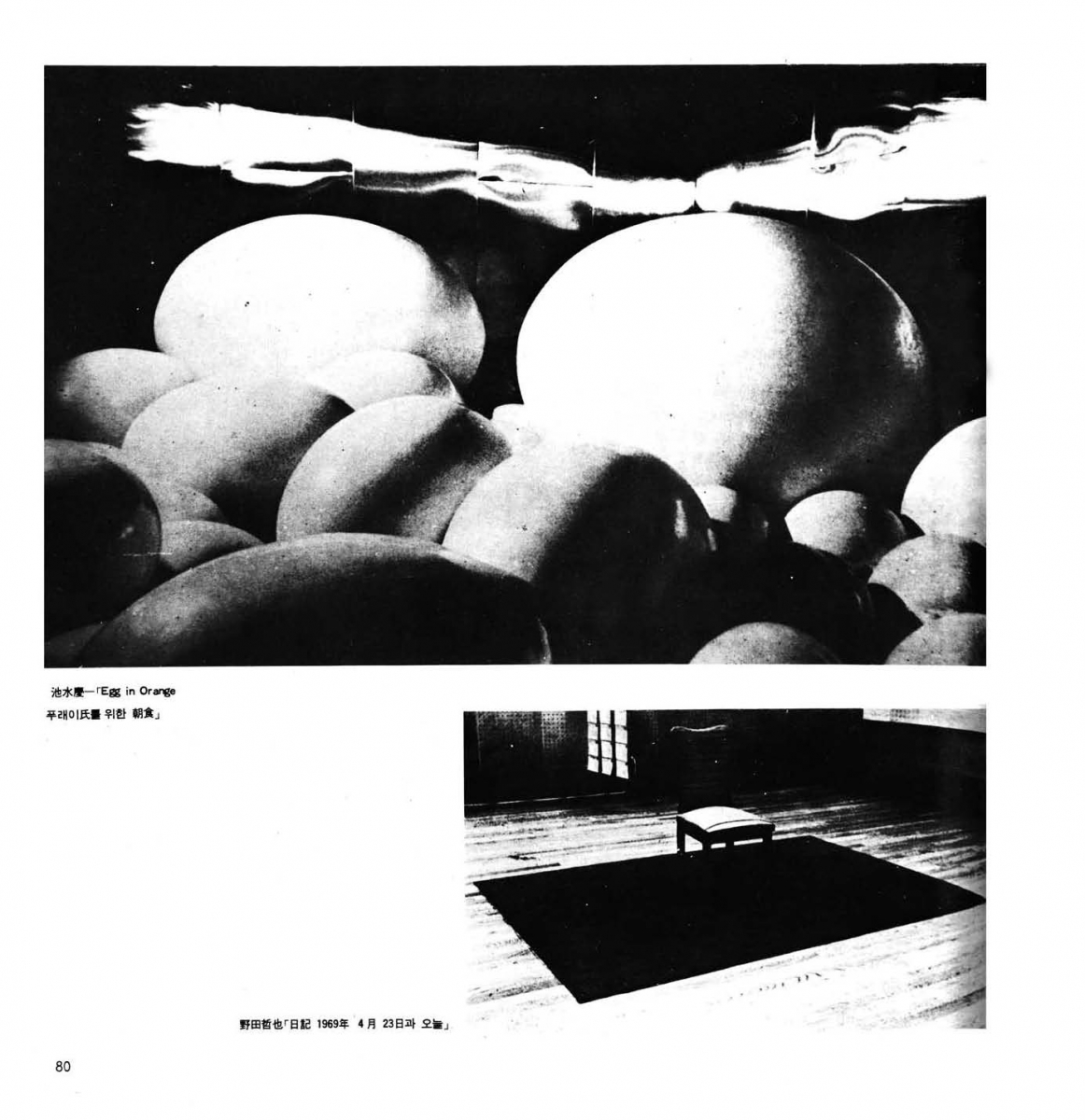

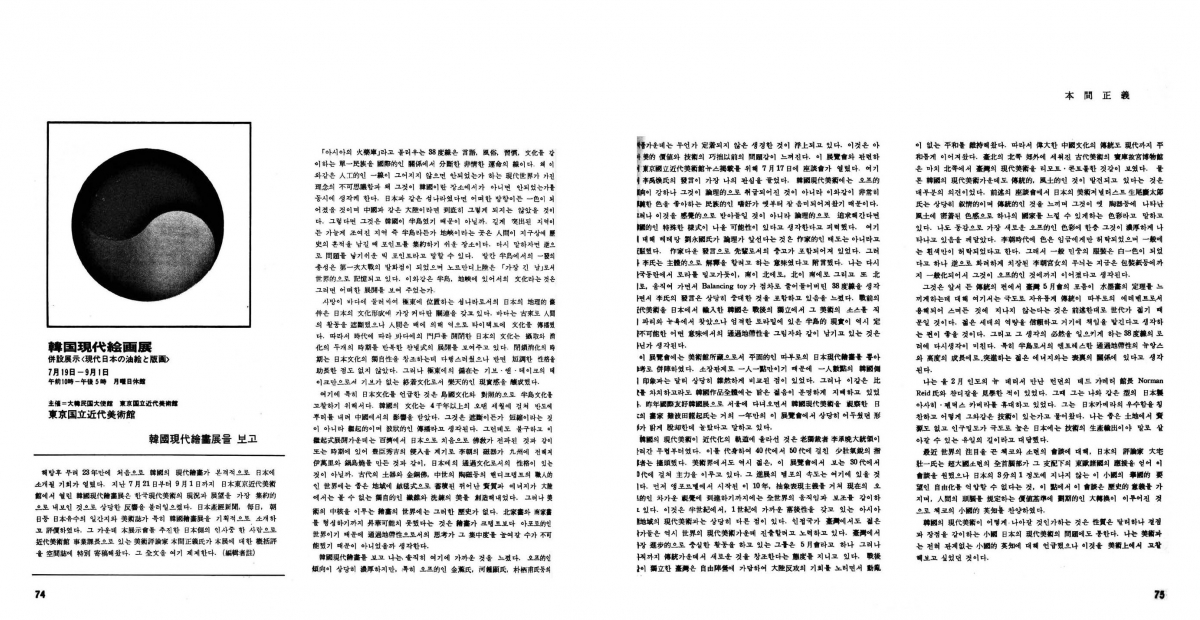

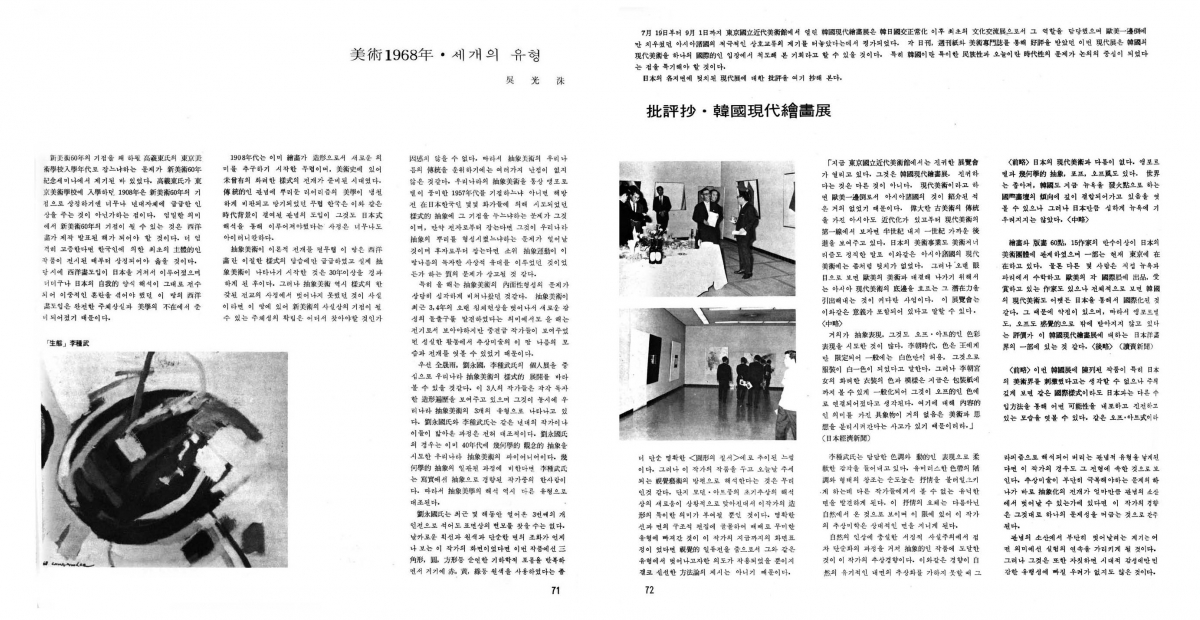

Lee Ufan (1936 – )’s ‘Trends in Japanese Contemporary Art: Focusing on the Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition’, published in SPACE No. 32 (July 1969), is a flare that sends a signal of the ‘Lee Ufan Effect’ that lit up Korean art in the 1970s. This article, in the form of a review of ‘The 9th Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition’, offers a vivid impression of the rapidly changing state of Japanese art. It suggests that institutional-critical attitudes were prevalent in Japan (‘Having doubts about the significance of exhibitions … controversy over the question of whether art itself – beyond just contemporary art – has a value for life, essentially’), and the threedimensional structure, which does not belong to any fine art mediums such as paintings and sculpture, predominated (‘Oil paintings, Japanese paintings, and Three-dimension A [sculpture] are declining, and Three-dimension B [Three-dimension] is dominating’). But this anti-artistic attitude is not so new or surprising. The problem is that something beyond that gesture of denial or resistance was taking place. Most of the works submitted as ‘Three-dimension B’ consisted of untreated, artificial or natural objects such as cloth, steel plate, sponge, paper, balloon, water, soil, and wood—presented without any specific or visible manipulations. Takamatsu Jiro lays a huge cotton cloth wrinkled on the floor, and Sekine Nobuo fills the rectangular and cylindrical containers made of black steel plates with water. In another exhibition, he placed a large and thick steel plate on top of a huge cylindrical sponge. Ikemizu Keiichi filled a room covered in stainless steel with huge polyester eggs and turned on a light bulb. Noda Tetsuya placed a chair on a black carpet.

SPACE No. 32, p. 80.

As if aiming at capturing a public that understood the aforementioned works as influenced by American pop or minimalism – due to the use of readymade products or their simple forms – Lee Ufan stated that they do not express objectivity like pop-art nor a self-contained nature like minimalism. Instead, he indicated that they were ‘works that enable the perception of a structure that seeks to recognise something larger and more holistic than itself’. According to him, they do not create another kind of an image or object, but rather provide an encounter with the world itself, which is revealed only when those things that have always been anthropomorphised and objectified are discontinued. In that world, the distinction between the subject as the creator, the objectified shape, and the space in which it takes place disappears. In fact, the phenomenological experience of these works is not reduced according to the artist’s intentions or plans, but rather follows the actions of various forces. The physical properties of cotton cloth encounter gravity, and the water that is filled in the cylindrical container reflects the changing sky. The polyester egg structure that moves every moment is reflected across the stainless steel. People who walk by the chair to sit on it leave their footprints in the carpet. Moreover, though not mentioned in this article, the ice works submitted to this exhibition melted over time. Who is the creator of the work? Is it the artist, material, gravity, audience, or temperature? Lee Ufan also introduces the work that he submitted: ‘I laid three large pieces of rice paper (2.1m × 2.7m × 3) without overlapping them, without any manipulation, intact on the floor of the exhibition hall. But I will leave it to the audience to imagine how they will feel’. The tip of the rolledup rice paper will continue to make a subtle movement in response to the movement of the audience and the flow of air. The experience of these works diverges from an assumption of the artists’ control and allows for the action of external influences. In this way, a work always reveals a world beyond itself. As such, the emergence of art as ‘a Dharmakāya that is both a medium to enlighten the world and the world itself’ is not a trend that is triggered by chance. It is an aesthetics of the present, when production is automated due to the ‘development of technology’ and the smallness of the earth is recognised anew with ‘the advent of the space age’, and thus human beings are no longer ‘the scale of all things’ or ‘the centre of the world’—namely, an aesthetics of extinction of human life. The title of his aforementioned entry was ‘Things and Words’. With this, he pays tribute to the anti-humanist Michel Foucault, who elaborated upon the death of human beings, with a slightly twisted title derived from the title of Foucault’s The Order of Things (Les Mots et les choses, 1966).

SPACE No. 23, pp.74 - 75.

Consisting of refined concepts, a clear logic, and a solid argument, this article is not a mere review of an exhibition. Rather, this exhibition was used to affirm the writer’s own narrative. In fact, in March of the same year, Lee Ufan received a prize after submitting ‘From Things to Existence’ to the call for art criticism at Art Publishers in Japan, coming to emerge as the most noteworthy art critic in Japan. Here, regarding the recent trend in Japanese art in which unprocessed materials such as wood, stone, and paper are installed in their original state, he claimed that this approach sought to reveal a sense of ‘existence’ as it is in the world, unlike other methodologies or approaches that present the ‘thing’ as a proxy for the artist’s conception. And he says that such an attempt goes beyond a colonialist modernity that distinguishes between the subject and the object and that objectifies other person according to the ideas and needs of us all. In his writing, which summarises the aesthetic and philosophical meaning of this trend known as ‘Monoha’, he suggests that Japanese art is no longer a variant of Western art but rather one formed of a distinct philosophical foundation which he criticises in order to encourage a transformation in civilisation. How Lee Ufan came to earn a page spread in SPACE may not be unrelated to his success story in Japan. It is unknown whether he was recommended by Kim Swoo Geun or proffered by Oh Kwangsoo, but SPACE promptly introduced Lee Ufan – who has emerged as Japan’s best critic of his era – to Korean readers. This is distinguished from the case of confirming his verified reputation by publishing his ‘Introduction to the Phenomenology of Encounter’ in AG No. 4 (1971), an issue of the magazine of the Korean Avant Garde Association, and ‘The Identity and Direction of the Idea on Objet’ in the first issue of Hongik Art (1972).▼1

SPACE No. 25, pp.71 - 72.

However, aside from his recognition in the Japanese art world, he had already received attention in the Korean art world. He participated in the first largescale Korean art exhibition ‘Korean Contemporary Painting Exhibition’ (The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 1968) held in Japan after the normalisation of diplomacy in 1965, along with artists from Korea including Yoo Youngkuk, Lee Seduk, Jeon Sungwoo, Park Seo Bo, and Youn Myeung-Ro. However, it was his words rather than his works that made him more widely known. In an exhibition-related roundtable talk, Lee Ufan mentioned that Korean works tend to have something that is ‘off’, but this is not logically captured, and rather simply accepted as a national preference for favouring particular colours. He also indicated that sensuous elements must be interpreted logically. The advice of a young Korean-Japanese artist, who went to Japan shortly after entering Seoul National University College of Fine Arts in 1956 and has since been toiling in obscurity, must have quite bewildered them. On this, Yoo Youngkuk (1916 – 2002) responded that it was not an artist’s attitude to set upon the most logical solution, and retorted that, in such a case, the work is impoverished. This argument appears to have been the highlight of the roundtable talk, or the exhibition. Both articles – Honma Masayoshi’s ‘After Seeing the Korean Contemporary Painting Exhibition’ published in SPACE No. 23 in September 1968 and Oh Kwangsoo’s ‘Art in 1968, Three Types’ published in SPACE No. 25 in December of the same year – focus on this anecdote.▼2 A young artist’s bold comment and a senior’s sententious response must have been a highlight in itself. But, beyond that, Oh Kwangsoo’s comment that the argument refers to a ‘clear generation gap’ and ‘a difference in ideas facing the present age’ is accurate.

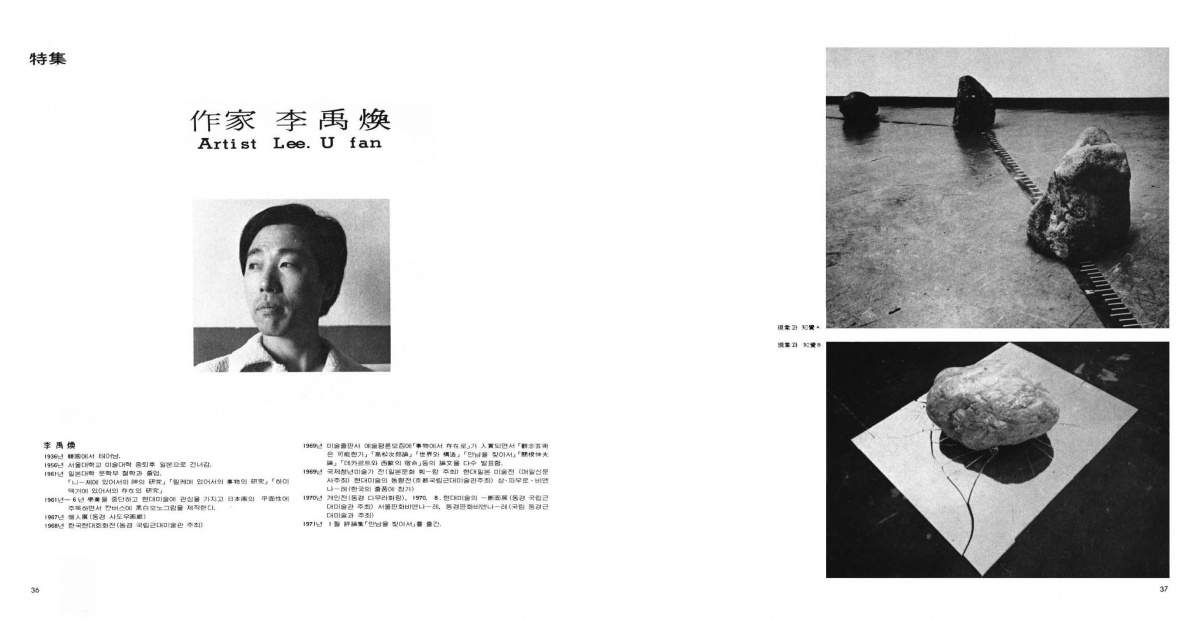

SPACE No. 100, pp.36 - 37.

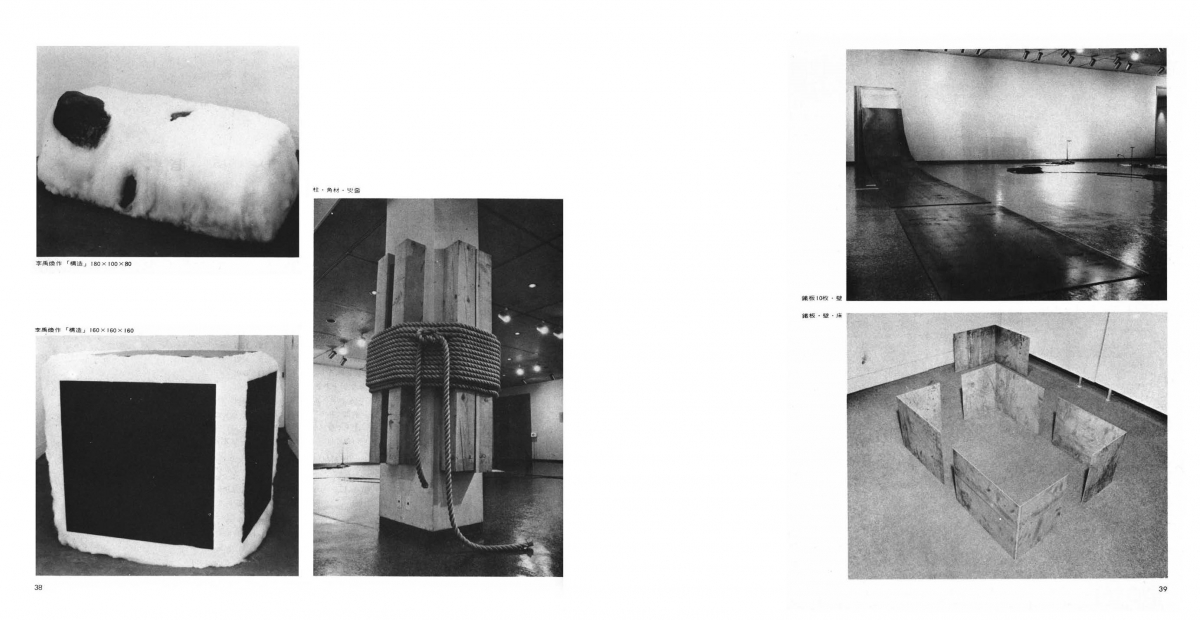

In fact, during the transition to the 1970s, Korean art was forced to be something that could be understood through contemplation rather than relying on a familiar sense of modelling to which one is accustomed. The ‘Lee Ufan Effect’ in the 1970s can be found at many different levels. One of the more direct examples is the emergence of wood, soil, and cloth in Korean art of the early 1970s. More fundamentally, in the mid-1970s, the work was increasingly reliant upon repetitive drawing, the trace of paint pushed out from the back of a sack of rough wool, or a trajectory of a drawing according to the measurements of the artist’s own body. Whether it is ‘monochrome’ or ‘event’, in this final visual action, the artist’s arbitrary decision-making was minimised, and ideas of expression, subjectivity, artist, or creativity become foremost formal challenges. Then, it was possible to say ‘I do not draw’, which is paradox. Now art had to be more logically explained and persuasive than simply providing aesthetic stimulus. In September 1975, SPACE No. 100 featured a special issue on Lee Ufan, announcing that he, who used to ‘incur such displeasure by squarely putting forth his art theory’ (borrowing the expression of Park Seo Bo, who was the author of the retrospective published), had now been hailed as a significant artist.▼3 The writings that reflect on personal relationships, such as being his colleague or fellow student, or that analyse his impact on Korean art, tell us that he is at a short distance from us in both the public and private realms.

SPACE No. 100, pp.38 - 39.

In our next issue Hyon-Sob Kim will cover ‘Discourse on Korean Contemporary Architects: Architect Yoon Seungjoong’, which featured in SPACE No. 236 (Apr. 1987).

------

1 Lee Ufan, ‘Introduction to the Phenomenology of Encounter’, AG No. 4 (1971), pp. 5 – 14; Lee Ufan, ‘The Identity and Direction of the Idea on Objet’, Hongik Art No. 1 (1972), pp. 86 – 96.