http:/http:///

▶ See the SPACE No. 79 (Oct. 1973)

One particular house caught my eye when scanning a large sample of 1960 ‒ 1970s houses, and made me laugh a little, emphasising a time in which all sorts of baseless abstract forms seemed to have been let loose. This is a design phenomenon which persists to this day. The house, labelled Residence of Mr. Song at Hannam-dong, first captures the imagination as a result of its form. The house could easily be read as a cartoonish form with an animal leaping out of it in the forest, owing to windows that suddenly protrude over the roof like pop-up headlamps on a sportscar, or even frog’s eyes, and a gabled roof which overwhelms the entire house. With the rooftop continuing down to the floor, the house emits an extremely foreign yet lovable charm, creating the unique impression of having been wrapped in a blanket or even appearing to be an ancient hut. Of course, from an architectural perspective, while it does come across as rather extravagant in terms of its form, it does also seem to clearly differentiate itself from other residential projects which doted upon the notion of ‘space’ in line with a Le-Corbusian ‘section intervening on volume’ or the Wright-school’s ‘organic – horizontal’ under the maxim ‘form follows function’. The design process whereby ‘function is forced into form’ seems to strike at the heart of the anti-formalist tendency, which is a unwritten law among majority of architects. The pages of SPACE No.79 (Oct. 1973) in which the house was introduced, reinforces the hypothesis that only elevation sketches can be featured with an absence of cross-sections, the so-called crowning glory of blueprints, and this is further reflected by the fact that scarcely any of the portfolios left by the architect thereafter feature cross-sections.

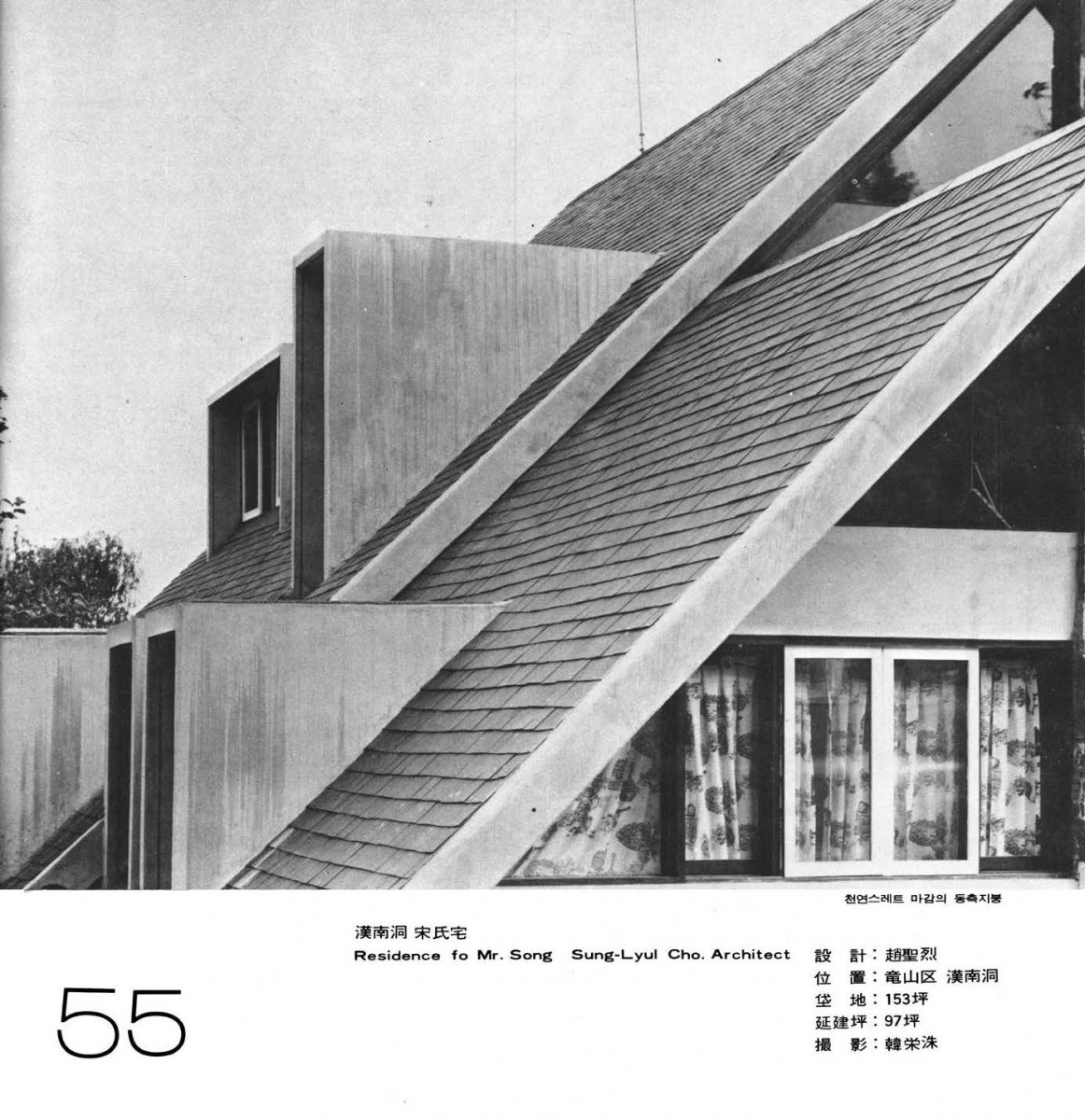

‘Residence of Mr. Song’, SPACE No. 79, p. 55.

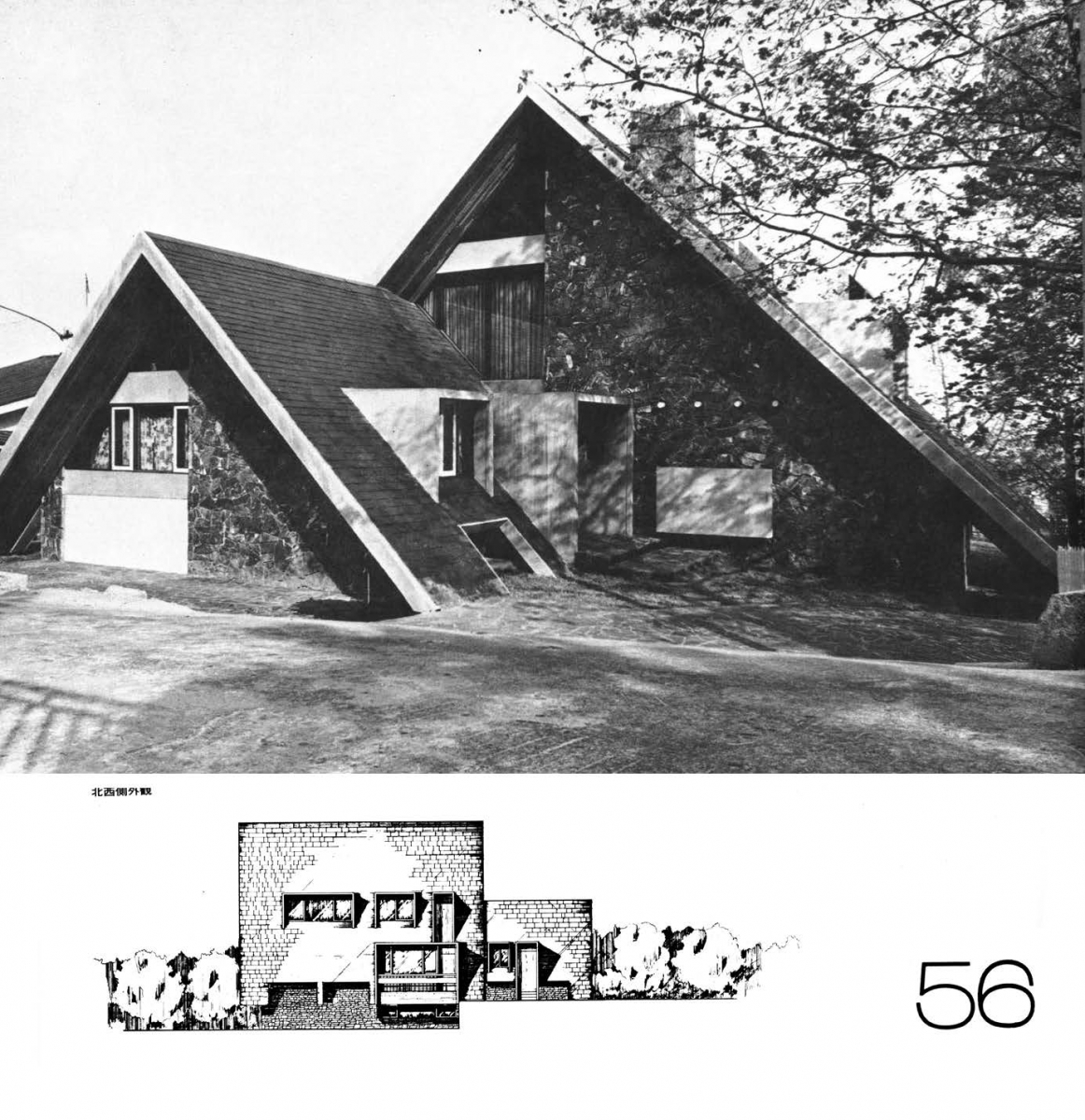

‘Residence of Mr. Song’, SPACE No. 79, p. 56.

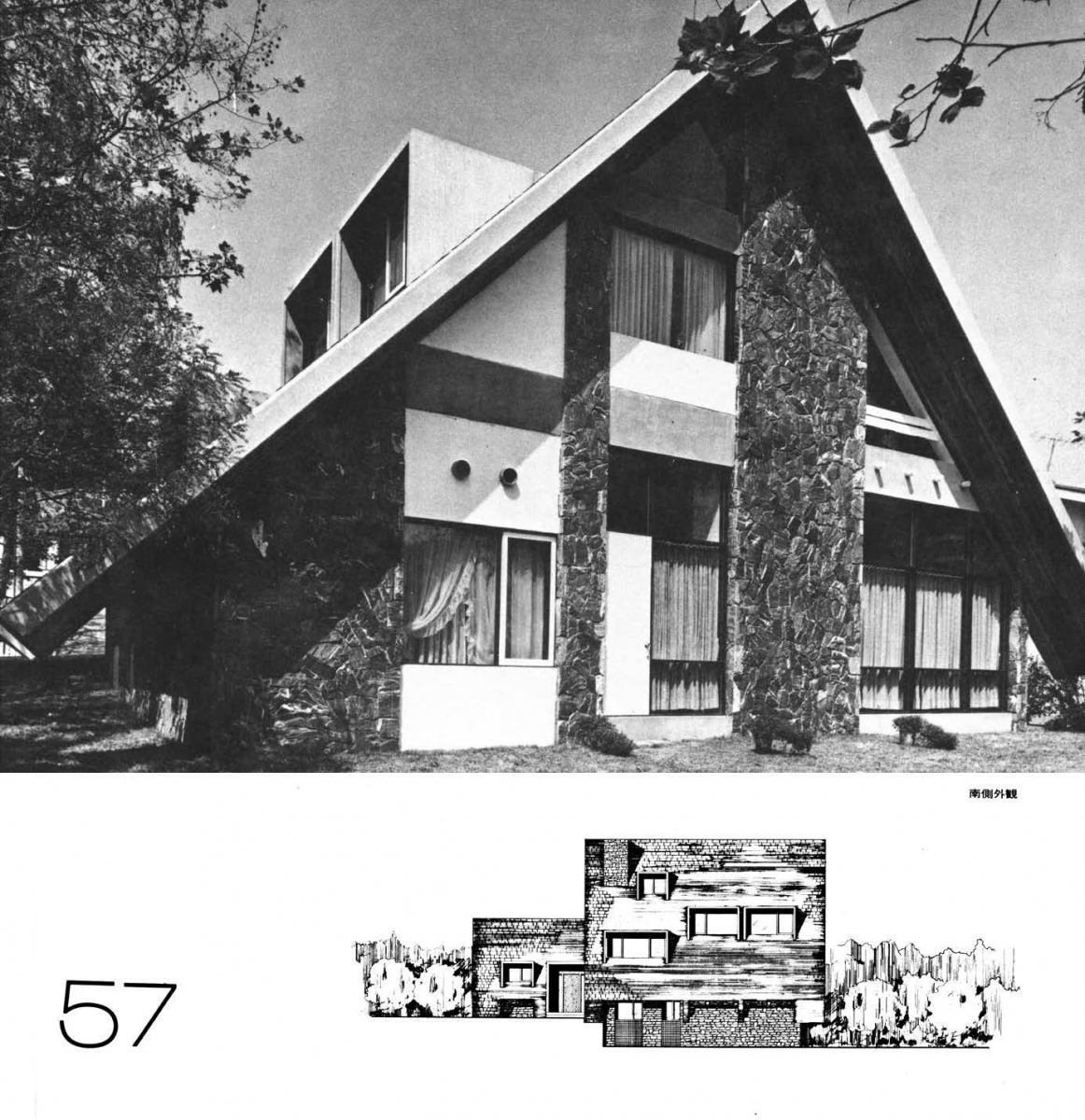

The Residence of Mr. Song at Hannam-dong features two similar large and small rightangled triangles joined together, facing downwards in a convivial manner and featuring a play of fractal geometry when observed alongside windows of various sizes which suddenly protrude perpendicularly from the roof. What augments this visual effect is the 45 degree angle of the roof, which can be seen as extremely unprecedented in a structure of this nature. While a gabled roof itself was a common form at the time, as they were mostly built with wood except for in particular circumstances, the slope would not exceed three tenths on average due to material and financial constraints, as well as the governing climate and cultural sentiments in Korea. However, the angle of the roof, put in place with a certain tenacity in the Residence of Mr. Song at Hannam-dong, derides all of the epochal compositional and cultural norms and can be seen to abide by distinct principles of its own, when considering the intense efforts put into the geometrical image—going so far as to create a 45 degree sloping slabbed roof. As a result, the house succeeds in appearing like a hut, of basic shapes and simple form, as the architect intended, expressing a mysterious tension between the figurative and the abstract. The house is intends to appear as such to all entering the site.

‘Residence of Mr. Song’, SPACE No. 79, p. 57.

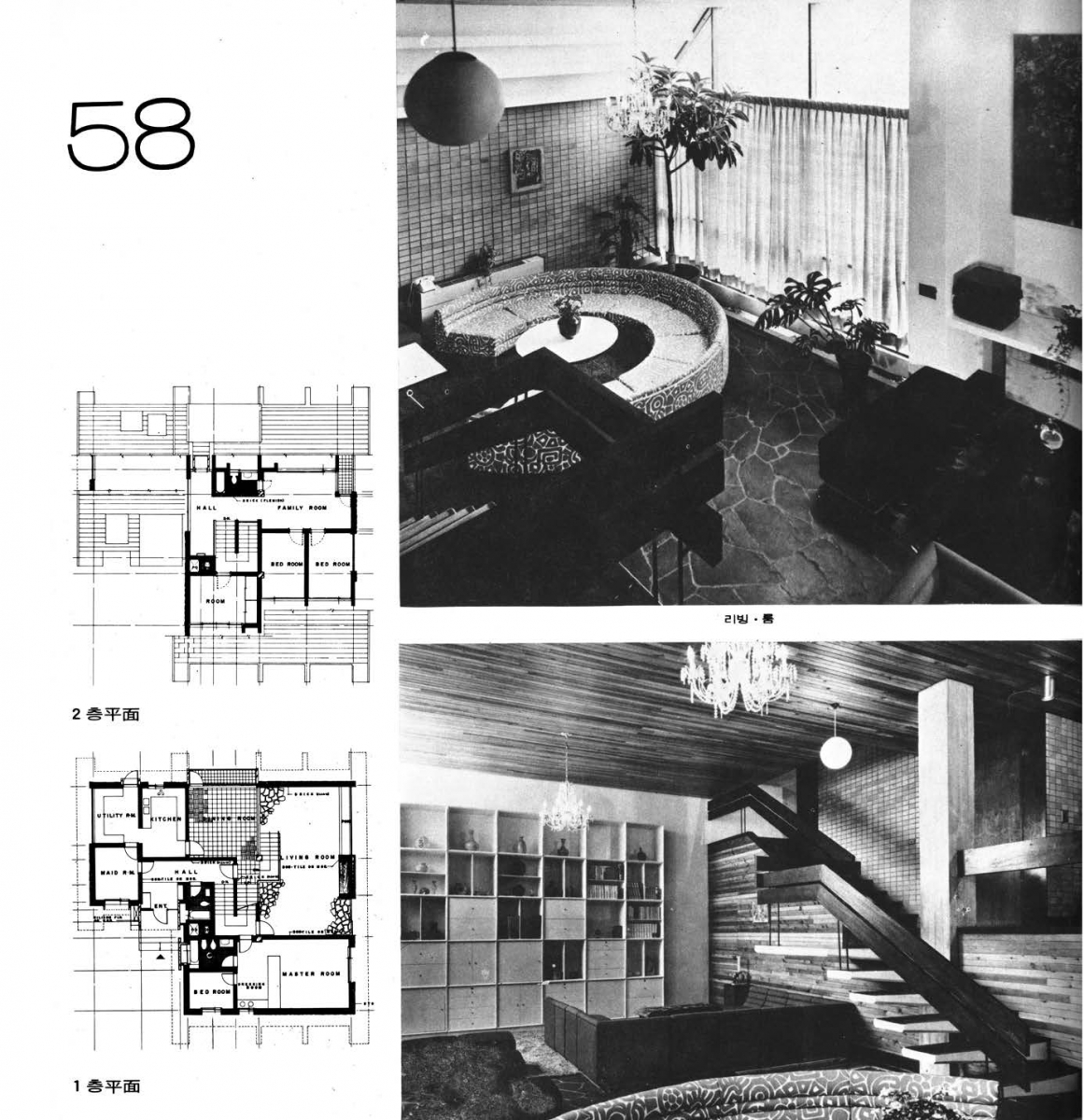

‘Residence of Mr. Song’, SPACE No. 79, p. 58.

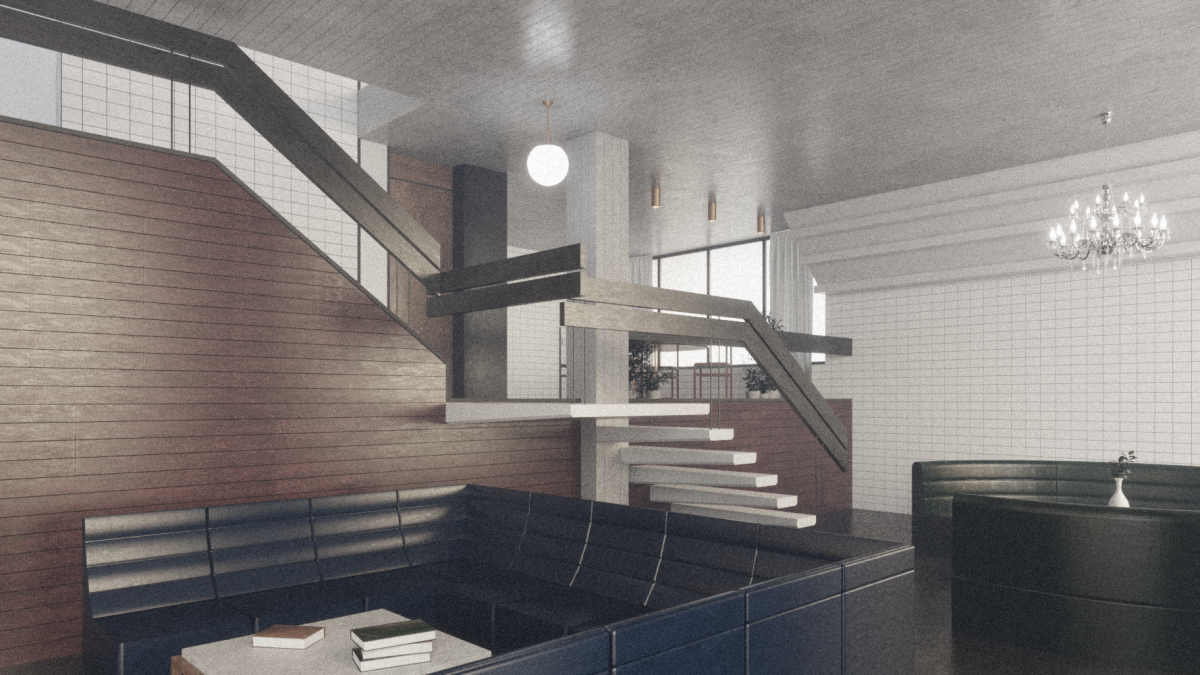

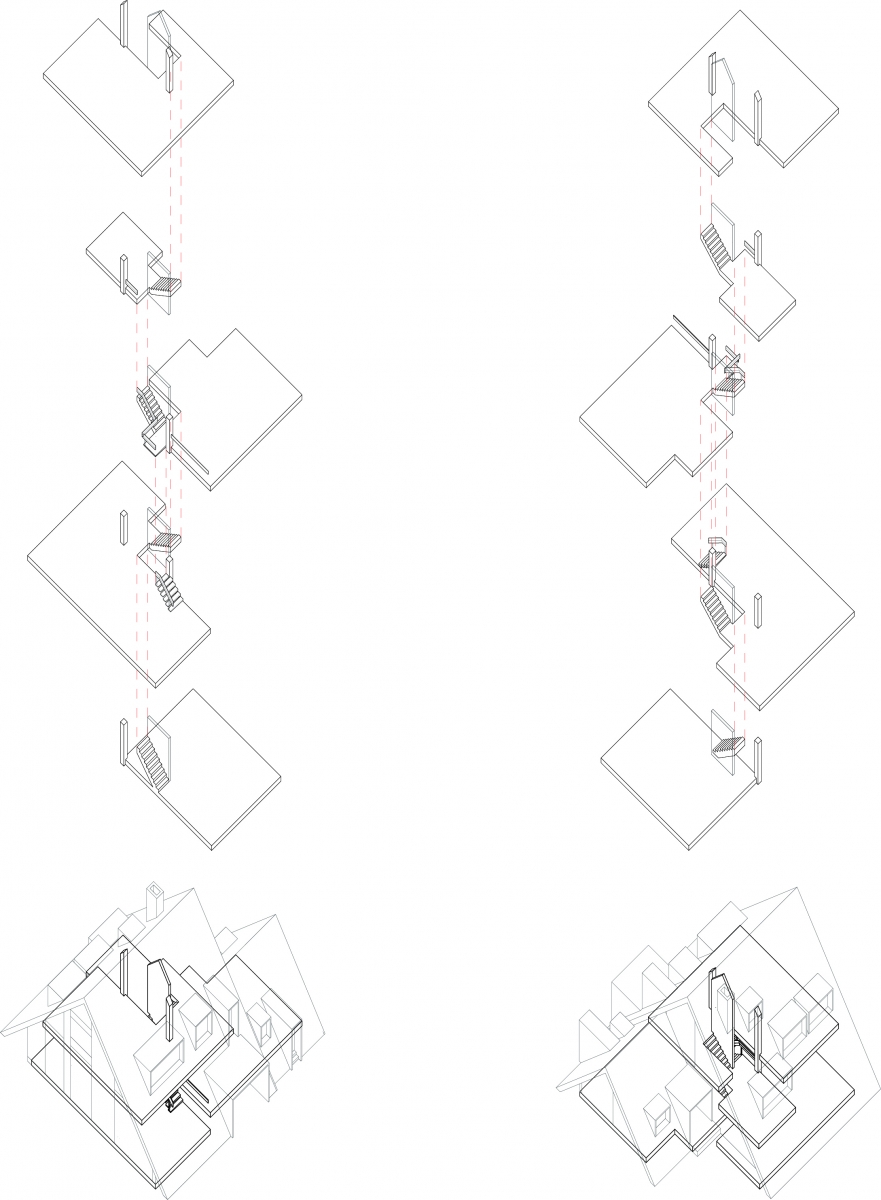

In cases where design conduct is determined by strict formal principles, the issue becomes one of resolving the function of the project, while the spatial composition featured in the plan provides an extremely interesting spatial experience as well as an overt function. Of course, the pre-existing difference in levels throughout the site plays a determining role, and yet the discerning eye of the architect, who has resolved these challenging conditions with vibrancy is something of note. The internal spaces are composed in a clear way, including the lower level thought to be to the south, the common areas like the living room which connect to the garden, and the higher level with service spaces such as the corridor, kitchen, and room for the guardian. The children’s rooms are gathered together on the second floor above the living room, completing the mass of the larger triangle when seen from the outside, while the kitchen quarters are single level which form a smaller triangle, with zoning and form naturally creating a sense of unity. Above all, attention must be paid to the stairs placed at the centre of the two spaces; while they seem to be nothing out of the ordinary, appearing like typical spiraling staircases, the spatial experience they provide is not so simple. With landings, the stairs are connected to diverse spaces, appearing to be a continuation of the corridor. Continuing on from the dining area, where a L-form wall which splits the middle, the skipped floor spaces connect to each other yet remain visually shut, resulting in a long perpendicular corridor within the house. This raises a sense of emotional tension by making it difficult for the residents to read the structure of the space at a single glance. Also, the protruding stairs on one side of the living room is more ornamental than functional, loosely deconstructing the functionality of the spiral stairs. This creates an image that one is observing part of a residential project by Adolf Loos, which in turn makes it regrettable that the two firmly blocked spaces (due to the wall placed on the lower level) are located at the same level. While it may not seem out of the ordinary, what was of undeniable fascination to the author was the floor just in front of the staircase which divides the living room and the corridor. This door cleanly dissects ‒ perpendicularly as well as horizontally ‒ the house, and it comes across as unfamiliar due to the location of the door. In most cases, an inner gate is placed in front of the entry to divide the entry and the living room areas, whereas, in this house, the inner gate is placed in the square middle of the house. Despite the fact that this ‘inner gate’ could have easily been drawn back towards the entrance, creating an open relationship between the dining area and stairs, a more conservative composition reveals that the interests of the architect were not solely focused on formal play. This simple gesture heightens the contrast between the mazelike internal spaces, disrupting a one to one relationship between form and space. Upon entering the living room, one passes through a quite low and dark corridor, opening the door facing one at the end, to be presented with a low set living room, and this would have been sufficiently attractive to the residents. Descending a couple of stairs down to the living room to sit on the sofa, then mounting up a little higher towards the dining area would also have given the sensation of a pleasant unfamiliarity.

A view of the living room (rendering: Jun Joonho)

A view of the dining area (rendering: Jun Joonho)

Spatial composition with central staircase (diagram: Jun Joonho)

When observing the overall relationship between form and plan, the Residence of Mr. Song at Hannam-dong is composed of a form in which spaces are divided up according to the form, rather than composing the form through the addition of spaces, and this can be seen as a quite different approach to the quite sentimental process of architects at the time. It is closer to the Villa Stein, proposed in the second architecture of the four compositions suggested by Le Corbusier in 1927, which Le Corbusier describes as the most difficult yet intellectually satisfying method. One might say it’s a type of game. The Residence of Mr. Song at Hannam-dong even adds a little wit, where the rectangular volume of the second principle has been changed to a triangle. As such, the house can be seen as a masterpiece which provides not only intellectual satisfaction, but also a sense of pleasure, a sense of completion of form, mathematical discipline, coordination of space, as well as kitsch attractiveness to the observer. The project is completely atypical, stemming from a different trajectory of thought, the (un)-ethical approach, which was more familiar when creating work directed by aesthetic scale by slightly altering a form which would have been discovered with dedication from space and function. Then, who precisely was the owner of this house?

The fashion designer Troa Cho (original name Cho Youngja), a major figure in the South Korea fashion scene in the 1960s, commissioned her brother, the architect Cho Sung-Lyul, for a residential home. Cho Sung-Lyul recounts this in his portfolio which was published in 1992.

architectural design must begin with a human understanding between the architect and the client. The architect can design better houses through an understanding and affection (jeong) for the person who is to live there. When the person to live in the house is someone close or familiar, one develops a sense of play (heung) from the onset of the discussion of building the house, which allows one to work with excitement (shin) to build a house of one’s dreams, a house which is good to live in.

For Cho Sung-Lyul – who had always emphasised the need for clients to develop a sense of discernment and refinement in the production of good architecture as an art – his little sister, a fashion designer who spent time working abroad, would have been the perfect client, offering a great opportunity to play out his skill in design. The Residence of Mr. Song at Hannam-dong, which was completed in 1973, was the last project that would coincidentally give proof to his architectural theory of ‘cubism’, as well as acting as a pilot project for him to properly launch the ‘cubist movement’. Cho Sung-Lyul would open a solo exhibition at the Shinsegae Gallery in 1972, and publish his portfolio at the age of 36. Here, as Kim Swoo Geun contests in the introduction, as ‘the first artist to publish his works in a single book’, Cho is ‘a perfectionist who has strictly managed his inner world without fault from the approach of a pure artist’. Cho Sung-Lyul would have been as acute a strategist as an artist.

Cho Sung-Lyul, who was born in Beolgyo of Jeollanam-do in 1936 to an agricultural home without many means, received church scholarships to graduate from Christian middle and high schools. Noticed for his talent in drawing from a young age, he was awarded in many an art competition, and this led him to dream of becoming an art teacher, whereby he immersed himself in graphic design and descriptive geometry, then belatedly joined Hongik University architectural department to study ‘architecture’ from Chung Inkuk, Um Deokmun, and to observe ‘architects’ from Kim Swoo Geun. He graduated in 1964, but experienced difficulties in gaining employment, meaning that he worked all sorts of part-time jobs at a printing house in Euljiro district, then entered Shinsegae Department Store in their yearly recruitment. Thereafter, he naturally concentrated on interior design and display, becoming known for Samsung Pavilion at the Korean Trade Fair (1968), external lighting ornamentation for the end of year at Shinsegae department store (1969) and his own work at his personal studio Apple Salon (1966), New York Shoe Store (1972), Pine Hill (1971). After officially founding the Cubic Design Institute from 1973, he launched himself into the second chapter of his life, and was awarded Korean Institute of Architects Awards for his Sunken Garden Building (1982), Yeun Kyung (1987), Troa Cho Art Center (1988) among others, and rose in the ranks through favourable recognitions for projects in Korea and abroad, such as design of the exhibition for the Independence Hall (1983) and the promotional exhibition for the 88 Olympics (1985). Nevertheless, there seem to be those who regarded this critically on the one hand, and it is highly probable that the seemingly basic cubic form, super graphics, bold tonal contrast and extravagant lighting and ornaments, would have been willingly dismissed as those of ‘a talented interior designer lost in shallow commercialism’ by his architectural peers who had followed what had long been as the ‘right path for (Korean) architects’. In particular, a great deal of gossip emerged from Cho’s direct management of the Pine Hill restaurant for which he adopted the slogan of a ‘sponsor business’, to which Cho directly responded:

why on earth should commercialism be critiqued so harshly? It is rather the effort to foster a health and righteous image within the confines of a strict and perfect commercialism. I am sure that hiding one’s intentions, and doing so in the shadows in a clumsy manner, gives way to more corruption.

Simply from the titles of the articles he wrote in the several published portfolios, one can say, without a doubt, that he was more than anyone else an artist, an architect, a designer, an idealist, and simultaneously a ruthless realist and opinion leader. I was left with many thoughts, after observing the cold manner with which a peer architect of the times wrote a one page critique about Cho in 1992. Even while it may be that I am aimlessly losing myself in delusion, as if I know it all…. (written by Suh Jaewon / edited by Kim Jeoungeun)

In our next issue, Cho Hyunjung will reflect upon the French Embassy in Korea by Kim Chung-up, which featured in SPACE No. 302 (Nov. 1992).

-----

1 ‘Feature: Works of Cho Sung-Lyul Architcture + Interiors’, SPACE No. 69 (October 1972), pp. 1 ‒ 51.

2 ‘Special Issue: The Modernism in Korea’, SPACE No. 306 (April 1993), pp. 21 ‒ 95.

3 Editorial team, Cho Sung-Lyul; the formal world of cubism, Hollym, 1992.

4 Cho Sung-Lyul, CHO, SUNG-YUL ART & ARCHITECTURE, Industrial Books Publication Public Agency, 1999.

5 ‘Architect Cho Sung-Lyul (Exploring Figures of the Century: 145)’, Seoul Shinmun, 6 September 1997.