Living Sejong, Reading Sejong: Questions After One Year

(1) The Development Background and the Current Situation

(2) The Characteristics of a Planned City

(3) Vitalizing the Local Community by Promoting Food Culture

(4) The Old Downtown and its Neighbouring Areas

(5) Roundtable: Understanding Sejong Today

extracted from SPACE no.621

Food and City Experiences

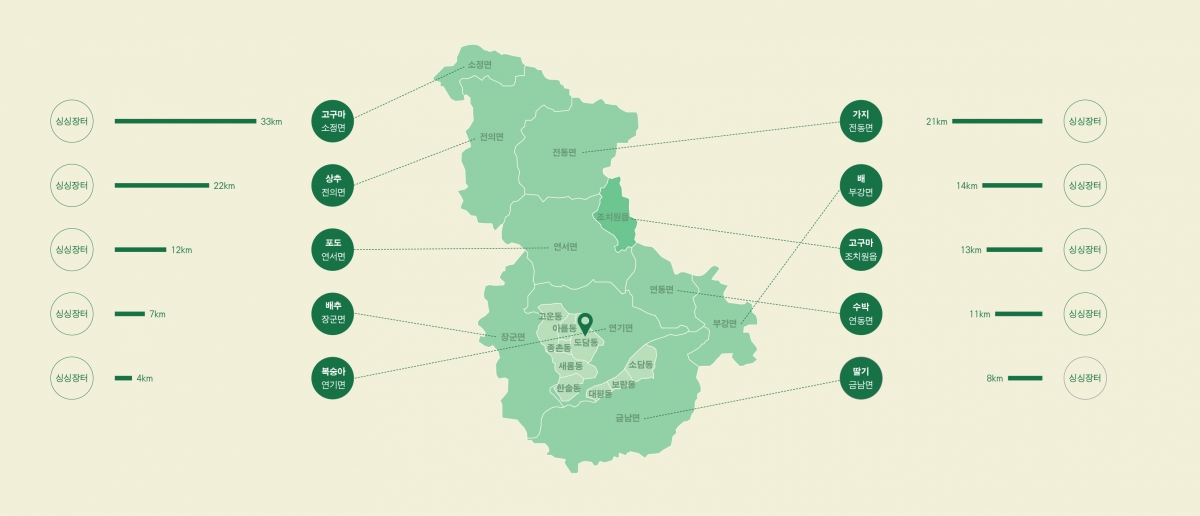

The sense of having settled in a city is often marked by familiarising oneself with where best to procure food, both in terms of dining out and shopping for groceries. Of all cognitive urban theories, the daily ritual of consuming food can be considered one of the most significant ways of establishing an image of the city. When I first moved to Sejong, it was not at all easy to buy ingredients. There was no problem when it came to buying a bottle of water or milk or ice cream, mainly due to the numerous ‘planned’ convenience stores or small mom and pop stores at each and every corner. However, the attempt to buy a certain type of apple or tomato would require diversion from this route. As a resident of Beomjigi village 10-danji, I had to take my car and drive to buy groceries at the large supermarkets in Cheotmaeul or Haengjeong town, which I found myself frequenting less and less. Not only was it quite far away, but my lifestyle and family routine did not require buying in bulk. It was around this time – when I had become used to a more minimalist mode of grocery shopping, which involved walking to the mom and pop store just by my house to buy a few pieces of fruit at a time – that I learnt of the nearby Shingshing Marketplace, a local food store in Areum-dong. It came as a surprise to find such fresh, delicious, and affordable fruit and vegetables, as well as rice cakes, so close to home. Only 15 minutes away by foot, it was also possible to buy a little fresh produce at a time. My daily diet began to consist of onions and tomatoes from Janggun-myeon, blueberries from Yeonseo-myeon, corn on the cob from Jochiwon-eup, crunchy peppers and tofu from Jeonui-myun, pumpkin leaves from Yeondong-myun and sticky black rice-cakes from Bugang-myeon. The Sejong local food store was first launched in September 2015 in association with the Dodam-dong Shingshing marketplace. The second store opened in January 2018 in Areum-dong, followed by two more, which are planned for completion by 2021. In 2018, South Korea recorded 229 local food store nationwide, with a recorded total annual revenue of 433.5 billion KRW in 2018.▼1 This is equivalent to an annual revenue of 2 billion KRW per local food store, and considering that the two Sejong Shingshing marketplaces grossed an annual revenue of 23.8 billion KRW in 2018, one can estimate and approximate an average of 11.9 billion KRW per store.▼2 This shows that Sejong local food stores are significantly more active than in other districts. Recently, food has begun to emerge as a central theme in both urban and architectural discussions. Experts stress how food can establish regional identities and increase the vitality of regions. Food can be thought of as a unified system that encompasses the processes of production, distribution, consumption and disposal, impacting the city’s existence and the allocation of urban space. In the year 2000 the article ‘The food system: a stranger to the planning field’ was published, which has become something of classic in the literature and forming a returning point of debate when discussing the relationship between food and urban planning. As the title hints towards, the discussion of food in the field of urban planning has been, more often than not, ‘unfamiliar’ or a ‘stranger’.▼3 However, the last 20 years have seen a change in circumstances, with food re-established as a central element in contemporary urban planning. The New Urban Agenda (NUA) adopted at the 2016 UN Habitat III Summit includes food security and nutrition in its Declaration on Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements, hence the calls for the reinforcement and diffusion of urban planning and design methods related to food.▼4 Some time later, in 2018, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) published an official report titled Integrating Food into Urban Planning. This report introduces the issues at stake influencing how regional food movements, including local food, have been integrated into urban planning and design, pointing to positive case studies from all over the world. The UN has promoted the importance of food systems in the establishment of better human settlement environments and in enhancing the quality of life. If so, what would be the appropriate way to publicize and discuss the relationship between food and the city in South Korea? While all of this had been loitering at the back of my mind, in the real world Sejong’s Shingshing marketplace had been growing at a phenomenal rate each year through growing customer satisfaction. This was a moment of revelation, my daydreaming aside.

The Urban and the Rural

Meanwhile, local food in Sejong is inherently different from the food justice paradigm proposed by the human rights based framework advocated by the NUA or FAO of the UN as a basic model when discussing food and urban issues. The phenomenon of the Shingshing marketplace can be interpreted as an extremely case-specific and exclusive example in which a new town with a central demographic of young middle-class intellectuals have used food to realise the potential of the coexistence of the urban and rural. Within this framework, a plethora of Sejong specific factors come into play, such as the demographic society, spatial environment, local governance and regional politics. From the beginning, Sejong was an urbanrural complex city that came into existence by forcefully shifting the administrative functions of the central government to a rural environment. The project departed under the premise of applying a fresh approach to resolutions and to turning away from existing methods concerning the issue of rural and urban co-existence. The majority of attempts, which were previously carried out in order to integrate or enforce coexistence between the urban and the rural, have mostly followed a pattern of zero-sum games in which basic services and public assets establish a game of cat and mouse. In comparison, Sejong has grown over the past five years by employing the familiar medium of food as a means of allowing the urban and the rural to coexist, yet this case has hardly been investigated in relation with Sejong’s urban and architectural environment. While the agrarian population and cultivated area (farmland) of the urban and rural complex city Sejong continues to decrease, customer membership, daily average consumption, annual revenues, and even the number of farmhouses registered to supply products have been increasing each year.▼5 What does these phenomena signify? Actively drawing upon the specificity of the spatial environment of Sejong, in which the urban districts and rural districts are connected through a unified administrative network, the local food movement has been influenced by regional politics. The regional politics of Sejong have been tooled towards promoting the successful cohabitation between the original residents of the rural districts and the migrants in the urban districts, and seeking solutions through food have become much more feasible than any other existing approaches with relatively small risks. Before the Shingshing marketplace opened its doors, Sejong opened sam-iljang and oh-iljang, directsales farmers market, in public land or the outdoor spaces of apartment blocks. Local food became one of Sejong’s central agendas, due to Lee Choonhui (mayor, Sejong Metropolitan Autonomous City) and the local food act that was legislated in April 2015, along with the establishment of the corporation Sejong Local Food as an agricultural corporation in June 2015. A collective investment fund was set up through a production corporation, SK, with a livestock cooperative, agricultural cooperative, and Sejong city, which resulted in the establishment of the Sejong Local Food.inc. A governance system was formed by producers, consumers, experts, government officials, and Sejong Local Food.inc, activating Shingshing marketplaces. Here, the specific local governance culture also contributes. Citizens use online forums to provide honest yet detailed feedback about food production and the quality of produce. For example, remarks on issues such as the quality of certain fruits produced from certain districts are here exchanged. The system of governance at play ultimately facilitates communication between the urban and the rural, sustainably supporting the growth of Sejong Local Food.

Food Systems and Urban Planning

Concluding with the sporadic outdoor markets, characterised by direct sales, the first branch of Shingshing marketplace at Dodam-dong came into being as a permanent market in a new building in September of 2015. Thereafter, the local food manufacturing support centre and the Shingshing cultural centre would respectively build and move into new buildings in April 2016 and November 2017. The second branch of the Shingshing marketplace at Areum-dong would also open its doors on a new building in January 2018. This was the result of providing a local food manufacturing centre to increase the added value of the food, and to activate a food culture by opening a cooking class in the Shingshing cultural centre, rather than limiting itself to direct sales of agricultural produce. An attempt to create a food cluster in the Shingshing marketplace Dodam branch, which even included a spacious parking lot for the convenience of its users, was a rational attempt and a meaningful evolution from the perspective of improving the food system. However, participation numbers in the cooking classes at the Shingshing cultural centre have not increased as much as the number of customers shopping at the Shingshing marketplace. This has been observed through the act of classification — consuming certain food products and participating in certain cooking classes are considered to be part of different cultural phenomena according to the specific cases of the Sejong demographic group, calling into question the need to search for a different, more appropriate approach. On the one hand, when comparing the urban and architectural characteristics of the Dodam and Areum branches, one notes in the dimension of the spatial composition of the architecture and the use of the boulevards, the fabrication of the Areum branch benefits from a better design including a public parking lot in the upper levels of the building. The Dodam branch may benefit from a spacious culture centre, parking lot and store, yet the arrangement and the association of each of these facilities, as well as the composition of the internal spaces, is pitiful due to their lack of attention to detail. This is not merely a problem specific to the Dodam branch, but also applicable to the urban spaces of Sejong. While Sejong provides largescale public facilities, such as the complex community centre, the details in the spatial design of urban blocks when it comes to an individual building integrating with the urban tissue of public open space and a street environment can become considerably awkward and banal. The fresh services proposed by Sejong Local Food as a new type of urban movement are particularly inspiring, yet the lack of novelty in the design of the local food stores and surrounding urban blocks as architectural or urban spaces to embrace these services is quite regrettable. However, both customer satisfaction and the number of customers at the Shingshing marketplace continues to rise, and hence, perhaps the regrets concerning good urban planning might not be the most pressing issue at hand.

1. Hong Yongdeok, ‘Rapid increase of 13 fold revenue in 5 years...yet, there’s still a long way to go for “direct sales of local food”’, Hangyoreh, (15th January 2019).

2. Sejong Metropolitan Autonomous City, Sejong Local Food Movement, 2019, unpublished report materials. Sejong-si documents; Kang Seungil, ‘Sejong, Shingshing Marketplace achieves 50 billion KRW gross revenue in three years and three months’, Sejong Times, (9th December, 2018).

3. Kameshwari Pothukuchi and Jerome L. Kauman, ‘The Food System: A Stranger to the Planning Field’, Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 66, 2000.

4. UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Integrating Food into Urban Planning, University College London Press, 2018. p. 22.

5. Sejong Statistics show that the agricultural population reduced from 16,335 in 2015 to 14,821 in 2017 while the area of cultivated land decreased from 8,260ha in 2015 to 7,958ha in 2017.