Living Sejong, Reading Sejong: Question After One Year

1. The Development Background and the Current Situation

2. The Characteristics of a Planned City

3. Vitalizing the Local Community by Promoting Food Culture

4. The Old Downtown and its Neighbouring Areas

5. Roundtable: Understanding Sejong Today

New Town: Differences between Ideas and Implementation, Architects and Planners

How can we justify planning strategies or design solutions that are used to implement an city idea in a physical environment? The concepts promoted by Sejong, by inviting a renowned progressive geographer David Harvey as a jury to select design competition entries, were democracy and equity. How could we explain the urban development process in Sejong, in which cities ideas proposed by architects at design competitions were brought down to earth and institutionalised after having gone through the phases of a master plan, a development plan and a construction plan? There is always dissonance between the two sectors of architecture and urban planning in discussing new town developments in Korea. Architects complain that planners have ruined the city with their lack of design sense, but planners argue that the city may not be operable solely through design ideas by masterpiece-mind architects. On the basis of documented city ideas and design competition proposals as well as the contents of official development plans for the Multifunctional Administrative City (MAC), this report explores how we approached new town projects, which include conflicts between those two parties.

Developed with the aim of ‘constructing 2 million housing units’ to ease a housing shortage in Seoul, Bundang functions as a bed town of the capital area. However, Sejong is a new town developed by relocating the main functions of Seoul with a national agenda of ‘achieving a balanced national development’ and ‘easing overpopulation in the capital area’. The time, background and objectives of the two developments are all different, but they seem somehow similar in appearances. How much do you think our society understands the development process of a new city? Under circumstances in which a serial process of planning, programming, design, construction, and sales is not properly studied, the era of third phase new town projects has suddenly begun. I suspect that our city development system represented by Bundang and Sejong has not changed much, but maintained a similar structure over the last 40 years. When a social problem emerges, politicians establish public initiatives, government agencies take actions, promotion/advisory committees are set up, and the Korea Land and Housing corporation becomes a main development agency and builds a new city in a flash. At some early stage of this process, urban planners and designers make master plans, but in most cases these plans are set up by relevant academic associations or research organisations, not by individual experts. Then private engineering companies turn them into a construction plans through district unit plans. There is very little opportunity for architects to take part in this system. Some may raise questions over whether architects must always be involved in it, but before that we have to ask why the system has developed in a way in which architects can’t participate. This firmly established system offers a huge advantage when building a new city in a very short period of time.

However, the development process of Sejong has some unusual aspects. Before starting New Administrative Capital Establishment, we tried establishing a concept more openly to define what kind of a city we might want. And we sought the answer from a number of architect’s proposals collected through International Urban Ideas Competition for the New MAC. Inviting architects who had been routinely excluded from city development processes and asking them for new ideas was a huge change that broke away from the more conventional approach. Nevertheless, considering the fact that the announcement date of the design competition was the 27th of May, 2005, and the start date of devising the master plan was the 26th of May, 2005, it was ambitious to expect that the design competition would bring about a significant change to the conventional development process of a new city. The winning entry to the competition was selected on the 15th of November, 2005, and in the meantime, the Korean Research Institute for Human Settlements, which was commissioned by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport to make the master plan, worked simultaneously on the master plan of Sejong. It couldn’t just wait and do nothing during the competition period. Yet its working process of how the master plan was established which shows how difficult it would be to implement innovative city ideas in our new town building system and to make them work properly.

The winning proposals translate the more abstract concepts of democracy and equity into various terms such as the centreless, the emptied centre, natural environmental conservation, ring-type circulation system, and a collective entity of 25 small towns with a horizontal hierarchy. After the competition, these terms were shared with architects and planners, but the freshness, delicacy, and complexity of the winning proposal’s city ideas were interpreted using a different tone at the master plan stage and then replaced with safety, familiarity and banality at the development and construction plan stages. Could this process, that I have observed, explain the essence of materialisation or execution in our new city making projects? It seems we are missing something here. What would that be?

If we can’t stop prioritising speed when completing the New Administrative Capital Establishment projects in the shortest time, would the conventional process of any new town developments not always remain the same? This discourse on speedy city-making implies that there exists a conflict of various interests, including profit. Before blaming planners for their lack of understanding concerning design or architects for their impractical, artistic ideas, should we not ask ourselves whether we can accept the abolition of the fast-building system that ensures the continued existence of the conventional city development method? Unless a collective consensus gathers around the notions that ‘it’s okay to build slowly’ and furthermore ‘it must be built slowly’, filters naturally into our everyday life, wouldn’t it be difficult to change today’s solid city-making culture represented by speed? When would be the right time to build a consensus to bring about change? Would such a time ever come? Perhaps, shouldn’t we accept the ‘fast-building’ culture itself as part of ourselves and find an alternative solution from there? The previous generation’s recipe for ‘success’, which helped them to overcome poverty in a very short time and to achieve rapid development, must have entailed some benefit in a return that would be paid off slowly and properly. However, with the unpaid bill left behind, we were forced to find solutions so quickly, again obsessed with speed. This irony can be found in Sejong too.

SPACE No. 620

Nature: Green Area Ratio, Environmental Preservation, and Landscape Design

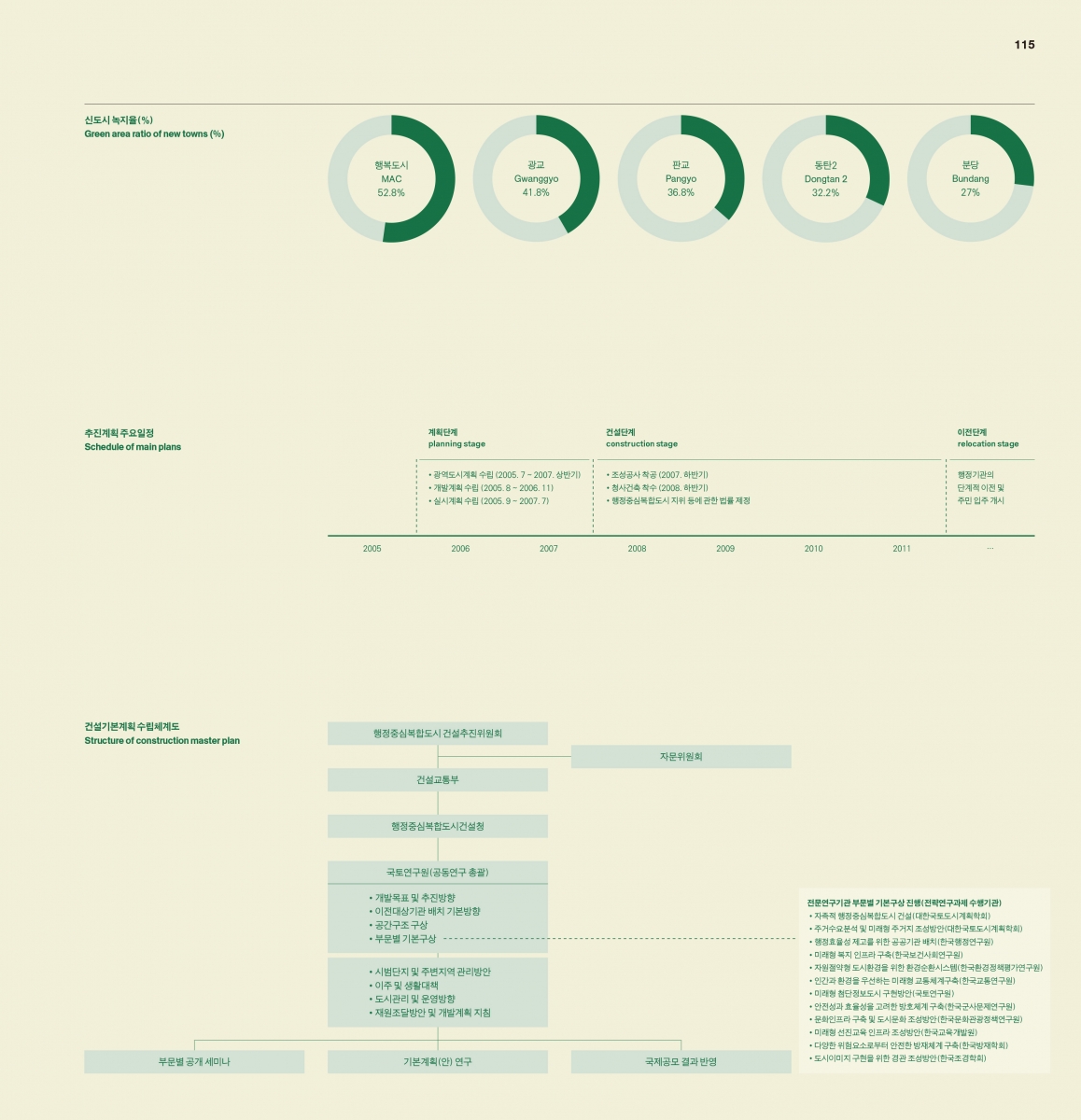

As a planned city, Sejong’s appearance is not that different to other existing new towns like Bundang and Ilsan. However, if you look at it more carefully, you can see the unique characteristics of its own in many places. One of those is the city’s park and green area ratio which is set to 50% and above. If we compare the green area ratios of new towns, Bundang is 27%, Dongtan 2, 32.2%, Pangyo, 36.8%, Gwanggyo, 41.8%, and MAC, 52.8%.▼1 Our new town projects have shown a constant increase in their green area ratio. It’s true that the number, 52.8%, was achieved after including riverside green areas in the calculation. Yet, it’s very noticeable that the ratio has exceeded 50% in Sejong. From a practical perspective, what does it mean to design a city using more than half the land area as parks and green spaces?

As a creation of man, the city has essentially always been in an antagonistic relationship with nature. Modern cities most especially took over natural territories and turned them into urban spaces. As Le Corbusier argued, the radiant city remodels inefficient premodern urban spaces in a practical way, efficiently providing new collective residential spaces and allowing all citizens to enjoy pleasant views and public greens. His vision of the ‘Towers in the Park’ addresses both the necessity of a planned city and the ambiguous identity of an artificial green area. New towns bring about a very complicated and ironic discourse on nature. Haven’t we tried to increase green area ratios as some kind of a compensation for having destroyed nature in order to build a new town rapidly? Hasn’t a unique perspective of our construction culture on cities and nature affected the increase of green area ratios in a distorted way?

It’s hard to define what comes first: if high-rise, high-density housing ensures an increase in green areas or if the attempt to provide more green areas leads to building higher and denser housing. In the case of Sejong, at its early development stage, in which housing types were determined, it was suggested that it should provide various kinds of low-rise high-density housing including town houses of five stories or less. However, it was not accepted due to a lack of available construction land and skepticism about the feasibility of its business practice. As a result, Sejong is now packed with high-rise apartment complexes. How much should we bear the hidden costs to achieve a higher green area ratio? Are new towns trying to prove that they are improving each time in this game of a green area ratio? We need to rethink these.

The city definitely has a high green area ratio. So then why can’t we find those areas in our everyday lives, and why do they only appear in certain places when they look as vast to seem too much? Quantitatively achieving a green area ratio of 50% or over is one thing and providing a welldesigned green space is another. Following International Urban Ideas Competition for the New MAC in 2005, International Design Competition for Central Open Space in MAC was held in 2007. Proposed at the competition, a cluster of a large-scale central park, arboretum and lake park is one of the features of which Sejong is proud. The winning entry ‘Ancient Futures’ suggested the basic design direction and placed a vast green space at the centre of a ring-shaped urban structure with an empty centre. Drawing in rivers and plains, connecting neighbouring areas with certain programmes, promoting the mutual development of city and nature, and using farms as a productive use of parkland rather than just providing a green space, the entry’s concepts seemed quite innovative. In 2011, however, the endangered Korean Golden Frog was discovered, and this meant certain changes to the initial plan. Environmental organisations, civic associations, and public institutions formed a consultative group, and they are searching an alternative solution. It means we need more time to see the completion, which would be discussed later following completion. On the other hand, the already completed lake park is now regarded as an iconic attraction in Sejong and is actively used by local citizens and visitors. Wellknown landscape architect Adriaan Geuze, who recently visited the Architecture & Urban Research Institute (auri) expressed his thoughts on Sejong, saying ‘Sejong looks quite interesting because the city itself is full of dynamism, but the lake park is rather disappointing, because of its insensitive treatment of the nature and its lack of design creativity’. In my experience, Sejong’s green spaces look more apparent around the Community Center and Welfare Center positioned on the other side of main streets, and along a pedestrian walkway-cum-greenway connected internally to commercial areas. The rich green pedestrian networks are indeed contributing to improving user convenience, even if their planting arrangements and the details of flooring materials are somewhat unsatisfactory. Ensuring convenient and safe use for wheelchair riders or the weak and the elderly, this green space creates pleasant scenery which cannot be easily found in other cities.

Daily Experiences: A Democratic, Citizen-Centred Idea, an Exclusive Government Complex, and an Entertaining Rooftop Garden

Contrary to my expectations, the most fun place in Sejong’s green parks that I visited during the last year was the rooftop garden of the Government Complex Sejong. It’s been promoted as the world’s longest rooftop garden, which is recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records for its length of 3.6km. Besides, the process of how this unique space was created is quite interesting. The identity as MAC can be manifested most effectively by the Public Administrative Town building. In this regard, the International Masterplan Competition for the Public Administrative Town of the MAC was held in January 2007, and ‘Flat City, Link City, Zero City’ was selected as the winner. Promoting democracy and equity as its overarching urban concept, Sejong set design guidelines for the competition to have a democratic, citizencentred government complex. They asked for proposals for a low-rise multi-use building design which would differentiate itself from other authoritative and exclusive complex-type office buildings, by providing an accessible place for the public and interacting with residential, commercial and cultural facilities nearby. I read these guidelines again, and it’s still surprising to see how progressive the concept of the Government Complex Sejong was for its time. Stating that government office buildings have to be open spaces for the public and local citizens, and provide a place for different departments to communicate and collaborate, and that they have to be low-rise individual buildings which can be interlinked with the city’s various functions and display the attitude of a servant not a ruler, these innovative guidelines are truly impressive even today. Are civil workers in these buildings designed under the concept of performing their work with democratic, citizen-centred approach and an open mind? I think I’ve heard the answer indirectly, and that was ‘no, not at all’. The completed Government Complex Sejong has inherited a low-rise curvilinear exterior from the initial masterplan, but the reality tells a different story by showing how confined, crowded and restricted it has now become. The tumult witnessed throughout the Design Competition for New Government Complex Sejong which occurred recently, seems to convey the same story. If the chief architect really respected the initial visions for Sejong and its design competition ideas for Public Administrative Town, then I think the right time for him to throw in the towel was not the day of the final screening but the day on which the site and scale of New Government Complex Sejong were determined, or, at the latest, the day when the competition design guidelines were drawn up.

The Government Complex Sejong reveals the differences between proposed design ideas and the physical environment in which they are implemented, and, furthermore, between concepts and practices. Even today, staffs across all departments are complaining about the inconvenience of the complex. Government Complex Sejong may occupy the centre of the Public Administrative Town and revert to an efficient and ordinary office building design. We should probably admit such a scenario was already preordained.

After the master plan ‘Flat City, Link City, Zero City’ was selected, ‘Hill Fantasia’ was chosen as the winner at the International Project Competition for Government Complex in MAC held in December 2007. It then entered the construction design stage and went through a process of modification, compromise and distortion. And all of these added up to the current form of today’s government complex. The rooftop garden is a place where you can trace the small fragments of the once impressive but now completely vanished initial design concepts of Public Administrative Town. Leaving these complicated discourses aside, the journey to the rooftop garden, in which I wait for my turn in a queue and walk all the way up to the rooftop garden, is just full of fun. Seeing well-trimmed flowers and trees neatly planted and grown on the hills of the rooftop is amusing. And more than that, walking along the meandering rooftop walkways and observing the scenery of Sejong at each scenic point on the way, presents unexpected pleasure. I wonder, does this rooftop garden count towards the green area ratio of Sejong?

Sejong Lake Park (Image courtesy of National Agency for Administrative City Construction)

Green path in the centre of Sejong(©Park Sohyun)

Rooftop garden of the Government Complex Sejong(©Roh Kyung)

-

1. The green area ratio have referred to the followings: the National Agency for MAC Construction; Korea Land & Housing Corporation; LH MAC Sejong Exhibition; Oh Sunghoon and Lim Donggun, 50 Years of Planned Cities in Seoul Metropolitan Area 1961 – 2010, auri, 2014

publications include Neighborhood Walking Neighborhood Planning (SPACE BOOKS, 2015) and ‘Seoul Streets—Ironic 5 Places of Urban Stories’ (SPACE, Mar. – Sep. 2017).