Living Sejong, Reading Sejong: Questions After One Year

(1) The Development Background and the Current Situation

(2) The Characteristics of a Planned City

(3) Vitalizing the Local Community by Promoting Food Culture

(4) The Old Downtown and its Neighbouring Areas

(5) Roundtable: Understanding Sejong Today

Prologue

Since I was appointed the president of the Architecture & Urban Research Institute (auri) in May 2018, Sejong has been my weekday hometown. Daily urban experiences in Sejong are full of wonder. Experts in architecture, urban planning and landscape architecture tend to express their dissatisfaction with this city, but many social indicators reveal that the satisfaction level of local citizens is not low at all. Despite numerous controversies around the ‘unconstitutionality’ of the capital relocation plan and the concept of the ‘New Administrative Capital’, Sejong has evolved into a home with a population of 320,000 within 10 years of its construction on site, representing the consummate ‘instant city’. I don’t have the ability to properly explain this city based as it is on decent urban theories. Instead, I try to briefly introduce what makes Sejong distinctive, even if the way I’ve experienced it may seem fragmentary. Communicating very personal thoughts and experiences, I have dared to write a series of articles as records because I am afraid to see my vivid impression of this city dissolve into a lost memory. I was abroad when heated debates erupted over the development of Sejong. As I was disconnected from those debates and was not involved in the construction process, I think I am able to make an objective and more whimsical observation of the situation. This series aims to readdress a number of oftdisregarded questions about urban phenomena that have become embedded in Sejong. I hope my discursive observations and questions can lead us to an earnest urban study someday in the future.

©Park Sohyun, 2019

Sejong is commonly associated with images that reveal it to be an extremely planned Korean city. The name reminds us of a landscape in which there are government office buildings of radical freeform design and vast green areas surrounded by highrise apartment complexes clustered in planned living spheres. I used to have similar thoughts about Sejong. But given the city’s total area, these images form a very small portion of the city. Sejong, officially called ‘Sejong Metropolitan Autonomous City’, has one eup (Jochiwon-eup), nine myeons (Yeongi, Yeondong, Bugang, Geumnam, Janggun, Yeonseo, Jeonui, Jeondong and Sojeong-myeon) and nine administrative dongs (Hansol, Dodam, Areum, Jongchon, Goun, Boram, Saerom, Daepyeong and Sodam-dong). So, Sejong is a new but also old city with many eup, myeons and dongs. Furthermore, Jochiwon-eup is considered as the city’s old downtown. The total area of Sejong is 465 km2 and the current population is 329,700.▼1

There are a number of interesting social indicators which are helpful for understanding the characteristics of Sejong. According to the Korea Happiness Report 2019 (2019), the place that shows the highest average happiness index in Korea is Sejong.▼2 In 2018 the national birth rate was 0.98, and Seoul, 0.76 whereas Sejong recorded 1.57 which was the highest in the country.▼3 In the Korean context, it’s a relatively young city with a lot of children. The Statistics Korea’s satisfaction survey on school life shows that the satisfaction level of Sejong’s middle and high school students is 68.3%, which is higher than the national average of 58%. The city has gained a high score particularly in the categories of school facilities and equipment and in school environment. We can grasp the meaning of these positive indicators, yet the reasons behind them have not been explained properly, only to the extent that they shirk alternative assumptions. It’s another factor that makes Sejong intriguing.

The Sociology of Opposing Movements in Relocating the Capital (2004) and The Making of Sejong City (2016) are two of the most interesting books about Sejong, which I read during my stay there for the last one year. The latter is a collection of writings by experts from various fields, who participated in the development of Sejong and later organised a club called ‘Sang-Saeng Hoe’, which means the winwin group. It has memoir-like writings which recollect the process in a delightful and boastful tone to mark its 10th anniversary. It informs us about who played what role during the construction process. The former, on the other hand, is a collection of 78 articles from among the writings of 48 opposition experts, published in major newspapers between 2002 when Former President Roh Moo-Hyun suggested the Administrative Capital Establishment as a presidential campaign promise and 2004 when the Constitutional Court declared the plan unconstitutional. It shows what kind of intellectual discourses existed at the time on the importance of a capital city and Seoul. While reading these books, standing on the sidelines from the present perspective, I could find new and surprising notions underpinning how we plan and build cities in Korea. Looking back over the supporters’ bright expectations as well as the opposition groups’ bleak predictions, some seem to make sense while others are merely nonsense.▼4 Predicting Sejong would become a prestigious global new town, an environment-friendly city promoting national unity and balanced development, or a sustainable city for symbiosis and growth, these positive expectations seem to ring hollow even today. The notion that negative forecasts made about the city will cause a huge slump in real estate prices in the capital area or will become a huge obstacle in terms of national unification or security have turned out to be completely wrong. This naive optimism or these groundless concerns are all embarrassingly interesting to me.

Overpopulation in the capital area and balanced regional development, the two largest discourses around urban problems in Korea, lie behind the development of Sejong. Let’s turn back the clock to the 30th of September, 2002. At that time, Roh Moo-Hyun officially announced that he would establish an Administrative Capital in the Chungcheong province region to relocate the Blue House and the Cabinet for the first time at an inauguration ceremony for an election polling committee. The goal was to ease crowdedness in the capital area and lead a more balanced regional development. I think the majority of people, both then and now, regarded the overgrowth of Seoul and the stagnation or decline of provincial areas as a serious social problem.▼5 However, there have always been disagreements on the correct strategies or methodologies for solving these problems. The opposing arguments against the development of Sejong obviously clashed particularly over whether capital relocation should be accepted as the main strategy for solving the two problems. With rapid modernisation and industrialisation, the population concentration of the capital area emerged as a problem in the 1960s. The so-called ‘Blank Paper Project’, an interim administrative capital development project in the 1970s, was also an outcome of these efforts to solve the urban problems of an overcrowded Seoul.

Here I begin to wonder why and how seriously we should regard the rural-urban or local-central imbalances, related to the population and industry concentration in the capital area or large cities, as a problem. Isn’t achieving a perfect balance practically an unattainable ideal? And wouldn’t forcing a balance become a more realistic goal when a certain degree of imbalance is permitted? In this context, what specific visions are we pursuing for our living environment from the perspective of balanced regional and urban development? Do we or did we have a solution through which to define and realise them? And can we translate and materialise such answers into spatial policy or design?

The slogans of this plan are based on the idea of balanced development, such as balance, equality, fairness and justice, are very important superordinate concepts indeed. But in reality, it’s not easy to find appropriate policies or specific methodologies that can implement them in practice. Until today, we haven’t tried hard enough to ensure efficient communication or to find a consensual solution. There must have been political considerations. Also, it must be acknowledged that every public policy and urban planning project has a political background.▼6 Nevertheless, the initial Sejong establishment plan, which suggested relocating the Blue House and the Cabinet, was indeed a progressive idea that could relieve overcrowding in the capital area and ensure a more balanced rate of regional development. Compared with the ‘Blank Paper Project’ in the 1970s, which had different approaches to political and planning cultures, and with the urban planning strategies of the first and secondphase new town projects, the discussions around the development of Sejong left traces that show the idea of balanced development was seriously considered and discussed with a much broader perspective in mind. But of course, through all ages, there has been no guarantee that the intention of a project will successfully lead to the outcome in reality.

Roh Moo-hyun, who made a promise to relocate the capital, became the President of Korea on the 19th of December, 2002, and the New Administrative Capital Establishment Planning and Support Group was launched on the 14th of April, 2003. After then, on the 29th of December, a special law for the New Administrative Capital Establishment got approval from the National Assembly by an overwhelming vote of 167 yeas to 13 nays. If a candidate with certain pledges won a campaign, then how much authority and binding agreements could those pledges have? And if a law was approved by the National Assembly, how much representativeness and legitimacy could the legislative institution have? Based on that special law, the New Administrative Capital Establishment Committee was launched on the 21st of May, 2004, and on the 11th of August it officially selected the Yeongi-Gongju region from the four candidates to be the project site. Here our uniquely fast-paced construction culture proved its speed again.

On the other hand, against the New Administrative Capital Establishment, opposition experts from various fields launched a professional forum in July 2003 in which share concerns on the project. The forum changed its name to the Capital Relocation Rejection Forum on the 2nd of January, 2004 and later evolved into Capital Relocation Rejection National Union while cooperating with civic groups on the same side. And this organisation played a key role in requesting a judicial review on the special law on the 12th of July, 2004. The Constitutional Court ruled that the special law was unconstitutional on the 21st of October, 2004, stating that the position of Seoul as the capital of Korea was covered by the customary constitution, and therefore the relocation of the capital required a constitutional amendment. Since the special law hasn’t followed this procedure, it is against the customary constitution. Through this ruling, we came to re-acknowledge the status of Seoul. As the capital of Korea, Seoul is as great as it’s covered by the customary constitution. What do we know about and want for the nation’s capital? Experts who expressed concerns about the New Administrative Capital Establishment can be largely classified into two groups: one has a dispute with the project itself, and the other doesn’t oppose the idea of relocation but finds problems in its procedure. Reasons for disputing the relocation of the capital are varied. According to some argumentative points of views in urban planning, they could be grouped as follows: ‘Relocation doesn’t ensure the ease of overpopulation in the capital area or balanced regional development’; ‘Relocation will cause a huge slump in real estate prices in the capital’; ‘National security will be problematic’; ‘Such a project must be based on a national consensus, but it’s ignored’; ‘The idea of relocating the capital to the Chungcheong region is anti-unification and will solidify the division of South and North Korea’; ‘There is confusion over social and regional disparities’; ‘We don’t have to keep all campaign pledges’; ‘The status as a hub in northeast Asia will be lost’; ‘Capital relocation means changes in the ruling powers’; ‘A capital is not something that we can build indiscreetly’, and so on and so on.▼7 These experts felt relieved, anticipating that the relocation project would be halted due to strong opposition and the ruling of the Constitutional Court.

However, it didn’t stop. The initial Capital Relocation Plan, which relocates the Blue House and all government institutions, was revised under the title the ‘Multifunctional Administrative City (MAC) Establishment Plan’. Another new special law for promoting this plan was legislated and promulgated on the 18th of March, 2005. This administrative city, in onomatopoeic words, ‘Happy City’ changed its title to ‘Sejong Metropolitan Autonomous City’ on the 21st of December, 2006 and officially announced its establishment on the 1st of July, 2012. And it has become what we see today.▼8

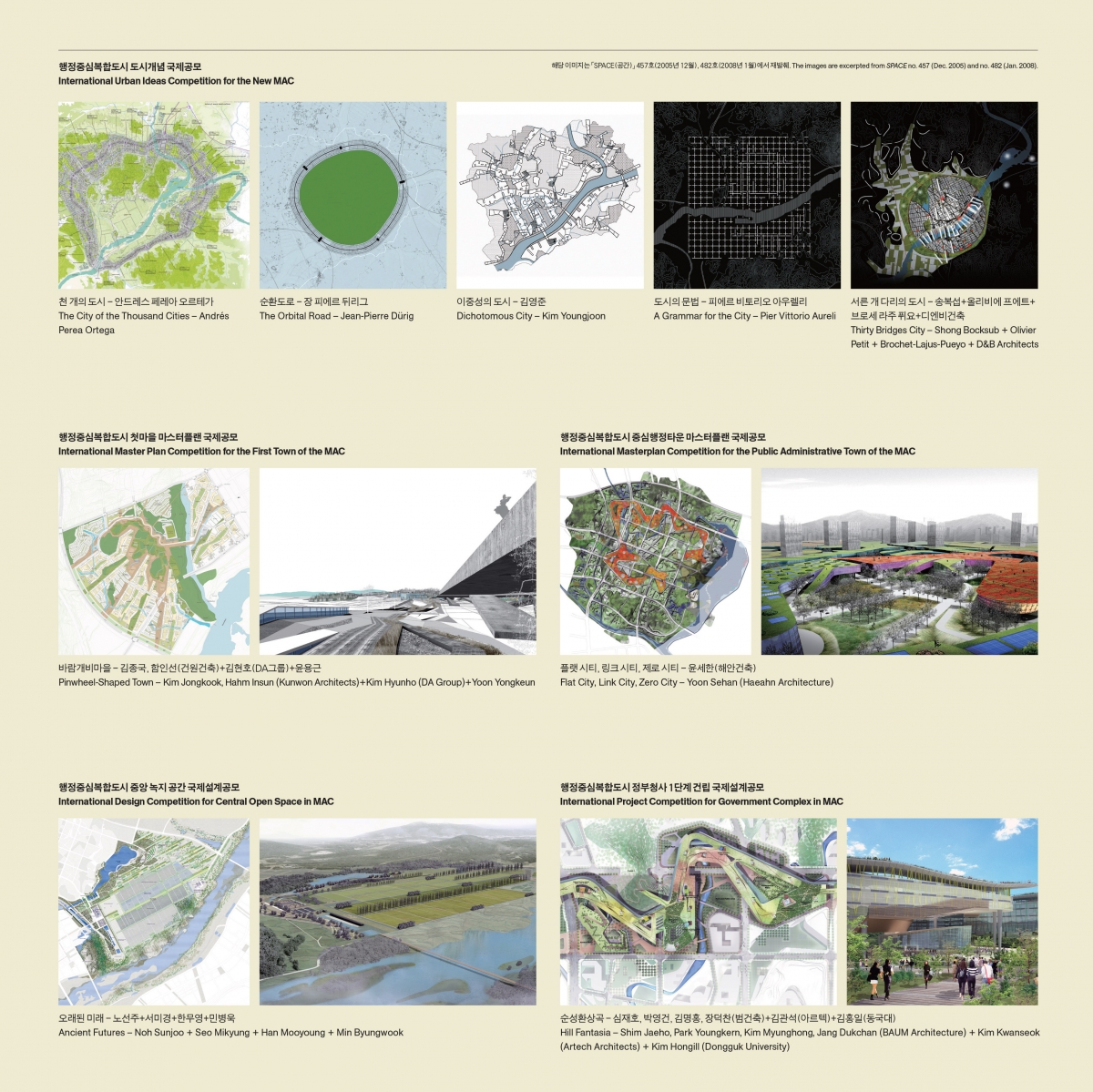

Since May 2005, when the new special law was again established, various urban design competitions for Sejong’s urban environment began to spring up. To make up for the fact that the New Administrative Capital Establishment Plan had been found unconstitutional, due to the absence of a national consensus and procedural problems, various kinds of international design competitions were held one after another with the aim of promoting cooperation, communication and the project itself, and also to confirm whether it’s truly an innovative solution. To name a few, the International Urban Ideas Competition for the New MAC held from May to November 2005, the International Master Plan Competition for the First Town of the MAC held from May to August 2006, the International Masterplan Competition for the Public Administrative Town of the MAC held from September 2006 to January 2007, the International Design Competition for Central Open Space in MAC held from February to October 2007, and the International Project Competition for Government Complex in MAC held from June to December 2007. The winning proposals of these competitions have been discussed in various architectural, urban and landscape design journals, including the special report in the January 2008 issue of SPACE. ▼9

Another noticeable reference on the development background of Sejong is a study of 2003 on the New Administrative Capital Establishment Plan. Through a public study proposal contest, a total of 37 subjects including 25 designated subjects and 12 free subjects were selected.▼10 If we look into the details, we see a section of intellectual mindsets in our society, in terms of how we regard national research and development projects in city building. They seem to demonstrate a shameful reality, in which doing research is one thing and implementing it is another thing. The professional research is not being used effectively and its results are volatilised. But still, there are some interesting studies. It is worth reviewing them to see what antirelocation authors and non-anti-relocation professors were concerned about, how their outcome helped to garner public support or consensus, and especially what meanings they convey to the present.

Despite many complications, Sejong has become an irreversible reality. It has grown to host a population of 320,000 in just 10 years after its on-ground construction began in 2007, based on the outcomes of a series of various design competitions. It is anticipated that it will soon become a home for 500,000 citizens. Unlike 2004, when the anti-relocation campaign arose, active discussions about constructing branch offices of the National Assembly and the Blue House are currently on-going. It’s time to analyse and grasp the current situation of Sejong more precisely as well as fully, and to re-examine its prospects for the near future. It will surely become a very interesting object of urban study.

-

1. The Sejong Metropolitan Autonomous City website, Sejong Statistics, [www.sejong.go.kr].

2. Choi Inchul et al., Korea Happiness Report 2019, Book 21, 2019.

3. Statistics Korea website [kostat.go.kr].

4. The next report covering another subtopic will introduce some of them.

5. Except for some urban economists, who disprove of the concept of growth management itself, including senior scholars such as Professor Harry Richardson at the University of Southern California, most experts see urban-rural disparities as a problem and do not deny the need for policy intervention by public bodies. Those who do not see imbalance as a problem tend to argue that such imbalances will exist anyway, and that population and industrial migration will continue until the market, not a public intervention, can settle the situation.

Peter Gordon and Harry W. Richardson, ‘Are Compact Cities a Desirable Planning Goal?’, Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol.63, 1997.; Marcial H. Echenique et al., ‘Growing Cities Sustainably’, Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol.78, 2012.

6. Various textbooks state that urban policies or planning are essentially not apolitical but political. John Levy, Contemporary Urban Planning, 11th ed., Routledge, 2017.

7. Complied by Kim Hyungkuk et al., Sociology of Opposing Movements in Relocating the Capital, Nanam Publishing House, 2004.

8. The contents about the development background of Sejong have referred to the followings: New Administrative Capital Establishment Committee et al., 2003 New Administrative Capital Establishment Propel Book, 2004.; Compiled by Kim Hyungkuk et al., Sociology of Opposing Movements in Relocating the Capital, Nanam Publishing House, 2004.; Compiled by Kim Anje et al., The Making of Sejong City, Bosung Publications, 2016.; The Sejong Metropolitan Autonomous City website, Sejong Statistics, [www.sejong.go.kr].

9. ‘The Public Administration Town: The Intermediate Connection in Building the MAC’, Space, no.482, 2008. The journey of developing from an urban planning idea into the framework of Sejong of today via the preliminary design and development planning stages is described in the July issue. 10. New Administrative Capital Establishment Committee et al., 2003 New Administrative Capital Establishment Propel Book, 2004.