Over the course of the past year, beginning with our preparations last September and proceeding with 12 interviews of Southeast Asian architects, this was the final interview in the series. When I first discovered Divooe Zein’s projects, it became evident that there was a unique approach and sensibility distinct from the work of other contemporary architects. My curiosity was piqued in numerous ways when the project mentioned the diverse means of understanding, approaching, and interpreting nature, and this compelled me to conduct this interview. The interface between nature and the artificial in The Forest BIG (2018) is a good starting point for our discussion.

interview Divooe Zein principal, Divooe Zein Architects × Park Changhyun principal, a round architects

Park Changhyun (Park): Although you may have been influenced by the Taiwanese climate, it seems to me that there is a lot of interest in the project’s contact with nature. The Forest BIG has a more tranquil atmosphere compared to the siu siu – Lab of Primitive Senses (2014). What is the most pronounced difference beween the two projects, seeing as they were structured with a similar approach and choice of materials?

Divooe Zein (Zein): The siu siu was a research plan initiated by our team in the Taipei Mountains. Centred on the theme of a ʻlearning domain in nature’, various elements of the project were organised with the help of a wide range of experts, including botanists, traditional medical researchers, indigenous peoples, climatologists, perfumers, spiritualists, and yogis. In this sense, siu siu is the predecessor and the source of the conception of The Forest BIG. To this effect, we used similar materials and programmes derived from siu siu that could be readily incorporated into this new project.

Park: My first impression of this project isn’t one of its artificiality, but of the natural connections it forges between nature, the existing building, and the circulation that separates the surrounding spaces. How did you intend to communicate an intimacy with the natural world to your visitors?

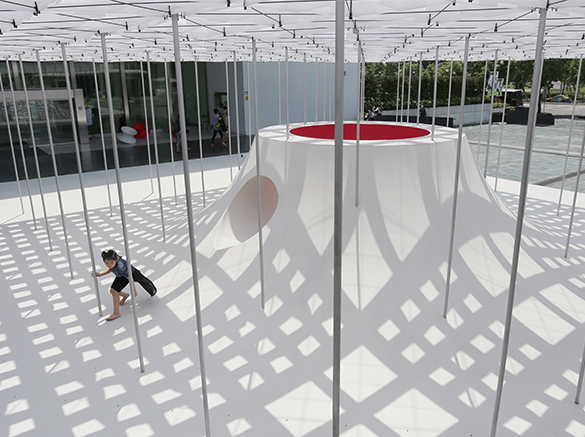

Zein: The foremost aim was to separate the forest from human activities, facilities, and buildings. As a result,

we tried to render the 300m circulation as a circular net greenhouse structure to define a clear boundary between nature and humans. This also acts as a protection system for visitors. I believe that people should maintain an appropriate distance from nature and not create disruptions, much like the architecture we find in the forest area.

Park: The journey to The Forest BIG is also worthy of note. The 10-minute walk to the site after approaching the area via transportation seems deliberate. What are some of the design decisions that went into these transitional spatial and experiential elements?

Zein: In my experience, walking alone into the woods, even if only for a few minutes, is like meditation and helps our mind and body grow calm through natural phytoncide. Therefore, the width of the path was designed only for individuals. During this 10-minute walk, one will encounter an eco-pond, a tree house, and vast tree areas all arranged along this little path.

Park: The main event space divides the courtyard and the pond. How does this mass interact with nature amongst the temporary structures and forest vegetation?

Zein: The main event space building was a ruin that has long existed. We actually found that the pond is of a reclaimed water system. It does not look always clean or smell pleasant. As such, we covered the building with netted mesh, and we complemented this with Lianas covering the rooftop to create a natural blurred effect.

Park: Our typical estimation of nature doesn’t include structures or defined paths but rather freer and looser movements. However, the defined circular circulation leads me to believe that there was a curator ordering a more purposeful experience. How did you balance the ideas of a freedom of movement and more delineated navigation?

Zein: The way humans receive messages through hearing and lighting, of an illusion from the glow, leads to irrational thinking. I think that this is what prompts your sense of singularity presented by the materials in the galvanized structure and the glossiness that makes up the entire space. Walking around, one will bear witness to the distinctiveness of the space and its materials.

Park: This project was designed in connection with the existing building structures. Could you say more about the existing site conditions and the modifications made? For example, why was the old bridge preserved?

Zein: The Forest BIG was a 10-hectare amusement park 40 years ago. Lots of entertainment facilities and play sets had been left behind, such as a carousel, a roller coaster, and a turtle pond bridge as well as many strange objects and an aquarium. My curiosity and nostalgia asked me to preserve some of these objects and to devise absurd combinations to create new designs, which were like archaeological traces of that former time in the site’s history. This approach, contrasting the design with the surrounding landscape, creates an experience that will otherwise never be consciously understood. The main building became the aquarium and the forest theatre was converted into the amusement park pumpkin greenhouse. The original trees were transplanted and a hole was vacated in the canopy to allow light in so that they will grow. Even the more sensory elements were considered as the pine bark floor connects the outside experience to the interior space.

Park: The most prominent material used is vinyl, which can also be commonly found in Korea on greenhouses. I am curious as to why you chose this particular temporary material for a project so deeply rooted within the natural environment and whether you questioned its sustainability?

Zein: Taiwan’s mountain climate is humid and rainy, making it difficult to control pests and crop diseases. In addition, the heavy rainfall brought about by typhoons causes further crop damage. Therefore, a preventive system of plant shelters assembled with nets is the most common agriculture construction in Taiwan. I believe that these familiar materials create an atmosphere unique to this location.

Park: Just as important to the project as the given environment and architecture are its programmes. What do you want visitors to take away from this place? How do you think the experience inside and outside the building differs?

Zein: If this place can provide visitors with a moment of peace and serenity, no matter the type of activity or programme, that would be a great achievement. Viewing and feeling through nature in a serene space is one of the most important aims behind this project. I intended to provide an experience of rediscovery, exploring familiar natural elements in a safe environment. To a certain extent, it also serves as a ʻnature workshop’ or a ʻforest ecology school’ that provides creative experiences with real, untreated gardens to help educate citizens on nature, plants and insects. To provide visitors with a partially comfortable experience, we imagined short journeys between a number unique interior spaces that add up to around 600m2. Visitors appeared to want the sense of a ʻnature classroom’ throughout the project.

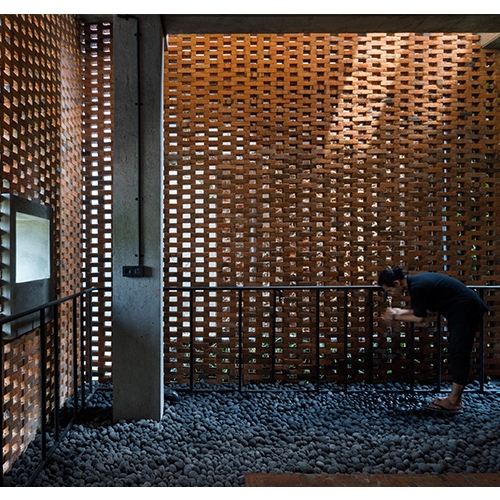

Park: There is much attention given to the atmosphere. Why were details such as the vinyl, which increases in transparency upon one’s approach, interior floors that reflect the heavy stones, and frosted glass and fog that blur the exterior view, emphasised in your design?

Zein: The primary function of the main building is the restaurant. It was designed to be a wholesome image of people picnicking in this wild sitting by the rock next to a stream. For this, we collected the huge rocks on site and gathered them for use as chairs, tables, and land art, while the frosted glass of a low, sacred lighting, instead of a simple transparent pane, was installed. I wanted the visitors to focus more on their deepest emotional connections with these spaces.

Park: Do you hope to bring this experience of nature into our bustling urban spaces or do you intend to maintain such projects as exclusive experiences that can only be appreciated remotely?

Zein: If we could create a place of serenity and calm in an urban area, that would benefit those living in the city. We live absent-mindedly in our everyday city life. However, when the environment changes, the body responds to adapt to our environment. The sensations and reactions of the body would strengthen and deepen our experience of place. When one returns to the daily life of the city after this experience, they already would have experienced a change of self. Therefore, city life and experiences here will form a connection. It was hoped that those calm, reverent, and compassionate feelings could be communicated and felt through the programmes here.

Park: I am curious as to how these programmes have been maintained during the pandemic. The scale suggests that it may be suitable for isolation and social distancing, but it must have affected the number of admissions.

Zein: We have suspended all activities as per the rules after the pandemic. In a way, it seems to be the providence of nature. We’ll soon be back with our originally scheduled programmes and events.

Park: The ‘Primitive Migration from/to Taiwan’ at the 2021 Venice Biennale enjoyed great success. Can you tell us about the experience of curating an exhibition of the projects that you have previously worked on, from planning to construction? Designing the circulation and experience of exhibitions must have been very different from your usual architectural work.

Zein: The concept behind the projects we designed, organised and exhibited at the Venice Biennale was consistent with our guiding architectural concepts. I hope that the atmosphere of the exhibition helped people to experience the glow of bodily sensations and a sense of serenity. Fundamentally, we started this project by exploring the effects of interactions between humans and nature. As such, the project exhibited at the Venice Biennale closely integrates into our usual work and concepts.

Park: The collaboration between various teams to stimulate the five senses through audio- visual simulations is very intriguing. Do you think it is possible to integrate the experiences of nature that you pursue in your own work into city buildings, and to foster cooperation between humans, nature, and technology?

Zein: That would be wonderful! Any effort or attempt to balance or rethink the relationship between our skills, mind, and technology would be critical in terms of engaging with nature in the city.

The two and a half years from planning to interviewing have not been easy. Unfamiliarity with different languages and cultures was one of the biggest sticking points. However, as I have talked to Southeast Asian architects based in Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Taiwan, I became acquainted once again with work that develops its country’s culture and architectural traditions through their own unique lens. I hope the twelve interviews will become a starting point that helps us to both stand in solidarity with others and to be aware of our current situation. In this spirit, I finish this series. I’d like to express my gratitude to all of my interviewees and readers.

Divooe Zein

Divooe Zein is the director of Divooe Zein Architects. He was raised in the Palau islands and studied at the international school SDA. After engaging in architectural practice for some years, he established Divooe Zein Architects in Taipei. In 2003 he began the journey and a range of field studies back and forth between the Balinese islands in Indonesia and Taiwan, to which he still commits his energies today. In 2014, he established the Siu Siu Lab of Primitive Senses in Taipei, and began teaching work in the Shih Chien University Department of Architecture in Taiwan.

Park Changhyun

Park Changhyun did his M.Arch and at the Graduate School of Architecture, Kyonggi University. He is currently the principal at a round architects. He won the 32nd KIA Award for his SKMS Research Lab, the Seoul Metropolitan City Architecture Award for his Joeun Sarangchae, and the Kim Swoo Geun Preview Award for his Jeju Mujindowon. He is also the winner of the Iconic Award held at Germany in 2019 for his Jeju Seoho-dong Residence. He has taught students at Kyonggi University, Hongik University, and Korea University from 2002 to 2018, and he is currently leading a project mapping the Korean architectural landscape by interviewing about 60 architects from Korea, Japan, and Portugal.

42