Architects in each country have taken their own steps and launched their own challenges to the generations that preceded them. Taiwan has witnessed a change in architectural topography in respect to the historical environment. To reflect upon the present situation in Taiwan, I have chosen to interview Shen Ting Tseng, one of the young architects in the fourth generation of Taiwanese architecture visibly expressing his own language. I was curious to hear his thoughts on architectural processes and the expansion of architectural boundaries.

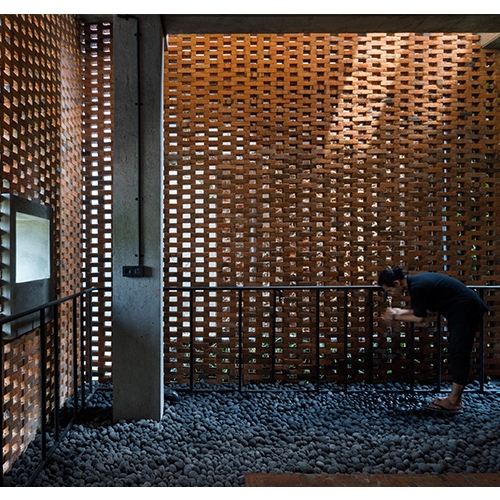

ⓒShentingtseng Architects

interview Shen Ting Tseng principal, Shen Ting Tseng Architects × Park Changhyun principal, a round architects

Park Changhyun (Park): Taiwan and South Korea have undergone a great deal of political and historical change since World War II. Architecture has also evolved in remarkable ways during this period. I would like to hear about Taiwan’s celebrations after World War II, and a brief introduction the current trend of Taiwanese architecture.

Shen Ting Tseng (Shen): Taiwanese modern architecture started before World War II, during the Japanese colonial rule. Between 1930 ‒ 1945, the Japanese introduced concrete and steel construction techniques while building vast infrastructural networks and facilities such as train stations, railways, the Monopoly Bureau, and sugar refineries. While post-war Taiwan experienced a renaissance in Chinese culture, in which the government encouraged the production of architecture with Chinese features, the idea of Western modernism had also begun to blossom simultaneously, resulting in clashes or independent occurrences of both concepts in architecture. 1970 ‒ 1990 was an era of rapid urbanisation—with the rise of local businesses and real estate, cities developed a higher density and further modernisation. At the end of the 1990s, as society had become more liberal as a whole and political ideologies had strayed from China, grassroots movements slowly gained momentum. As a consequence, architects turned their focus to real living spaces, attempting to create designs suited to Taiwan, sparking a diverse regional architecture movement that would stretch out over the years. After 2010, Taiwanese culture has been probed wide and deep, creating a colourful array of subcultural and online media, which in turn has shifted the boundaries of architecture. Art, temporary installations, exhibitions, and more others have become elements in architectural designs, whereas architectural thinking has strayed from regional limitations and morphed into a more basic, simpler, purer version of what it once was.

Park: This is connected to history of Korea, and the identity and interests of each generation follow the same historical stream. What do Taiwanese young architects choose to focus on and how is this focus changing?

Shen: The first generation of Taiwanese architects originated in 1915 ‒ 1935, predominately born in China and educated in the Western world, so their architecture was a discussion of the modernisation of Chinese architecture. The most significant architects during this era were Da-hong Wang and Chi-kwan Chen. The second generation of architects were born in 1935 ‒ 1955. They faced a rapidly developing Taiwan, when the economy was just taking off and cities grew with the development of real estate. As a result, they struggled to break through the boundaries of culture, business, construction techniques, modernism, and postmodernism. The representative architects are Chu-yuan Lee and Kris Yao. The third generation was born in 1955 ‒ 1975, when the political atmosphere became more liberal and people worked towards a democratic society. At this moment, regional architecture movements drew inspiration from people, the land, and the environment, attempting to open architecture up to and encourage the public. The representative architects are Sheng-yuan Huang and Jay Chiu. The fourth generation were born in 1975 ‒ 1985. In my opinion, this generation of architects were influenced by the former generation in terms of environmental thinking. However, regional influences were lessened as they accepted the world as a whole and fought against themes such as standardisation, globalisation, and capitalism. Perhaps it was modern art and the revival of architecture ideology, along with the privileging of architecture on a smaller scale that had the greatest impact on these architects, so they redirected their focus on internal expression and on sensory engagements with architecture, forming the basis of their attempts to return their labours to architecture.

Park: Architecture cannot exist alone. Considering architecture as emerging from the combination of culture and structural programmes, what attempts that concern cultural values are presently being undertaken in Taiwan?

Shen: Although architecture cannot be separated from culture, it becomes overly rigid when it is too eager to express cultural values. It is difficult for me to define the value of Taiwanese culture as people are still exploring the possibilities and values across every field, and even though people in Taiwan do have a unique lifestyle, Taiwanese culture is facing a time of rediscovery and reconstruction. For architects, a single reliable cultural source does not exist. We are retracing our steps to focus on individual experiences, no longer anxious to express our culture, but to continuously reflect and make new attempts.

Park: There are many of your projects that intend to create new spaces whether in existing buildings or in the city, to introduce greater dynamism for residents in the city. What do you think of buildings that bring people together and create new energy in the city centre?

Shen: Architecture sometimes accidentally obstructs living possibilities, so I like to think of architecture as a catalyst, deriving a livelier lifestyle from architectural assemblages, sometimes providing a chance for people to experience the exhilaration of change. Whether it is temporal or permanent event, the core idea of architecture as a catalyst is the same. However, this sort of architecture is often very noticeably decorated, like a cardiotonic that produces only an instant of life. I am against this approach; I want to create architecture that will coexist, depend upon or even collide with its existing environment, creating a new but profound flow in life.

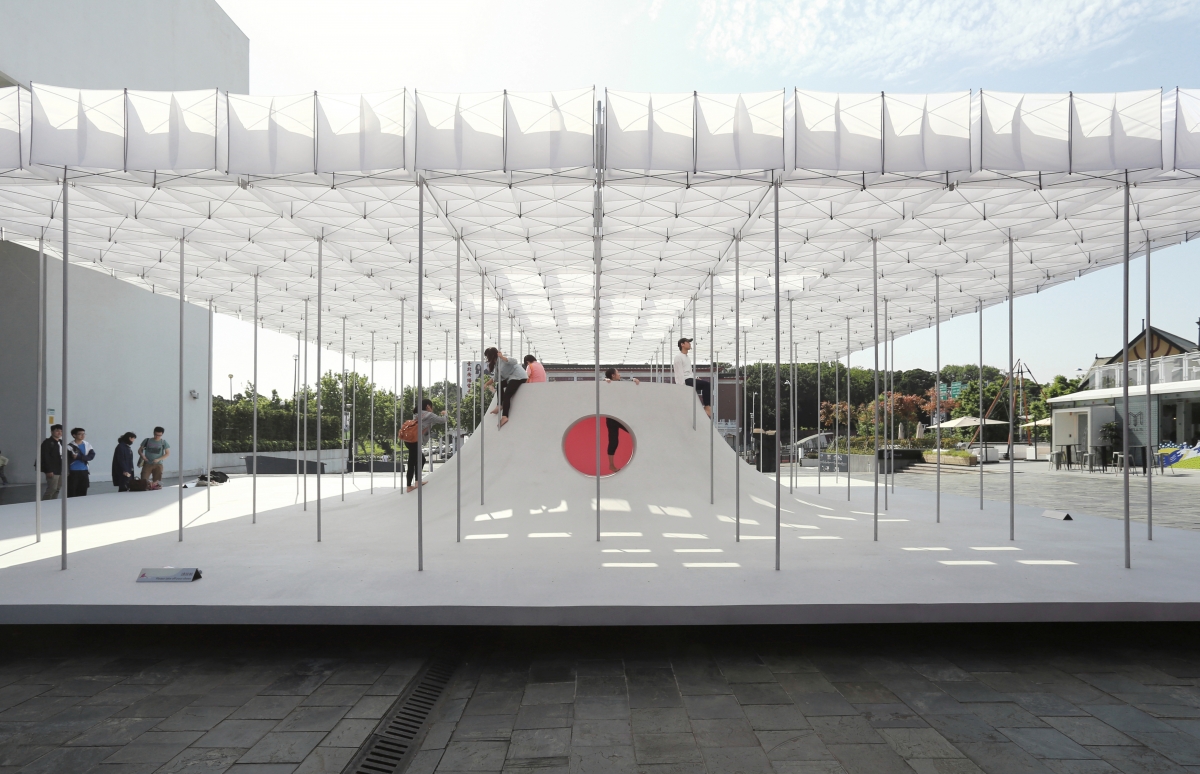

ⓒShawn Liu

Park: The extent of architecture’s impact on society is expanding. Regardless of the time when the results made in the place are present, I think the influence becomes more intense. In this sense, Floating Pavilion (2016) has the power to be approached by anyone and to subvert or change one’s existing impressions of the previous square. Keeping in mind the Floating Pavilion installed in TFAM Square for three months, can you detail any different situational changes?

Shen: Due to the strong winds and scorching sunlight acting on the pavilion, people could not experience the space in an ordinary way. During the three-month exhibition of the Floating Pavilion, we tried to capture this extreme bout of weather through half-transparent kites, turning this experience into one that could be felt and remembered. Once enraptured by a unique feeling in a space, people get attached, and this plays a major part in the pavilion’s sense of place. Temporal architecture tends to be more vulnerable and unstable, which further enables correspondence between the project and nature. On the outside, this pavilion may appear lacklustre, but it is home to rich natural elements of wind and light. When unstable architectural elements are met with natural elements, together they form a soft field on a scale suitable for people.

Park: At the time of the Floating Pavilion installation, did you have any thoughts about the connection of TFAM Square to the Taipei Fine Art Museum located nextdoor?

Shen: I attempted to create continuity in the architectural elements of TFAM, for example the grid the box kites created was a response to the grid beams in the lobby. Though familiar, the two kept their distance, one large and one small, like a parent and a child. Perhaps I wanted the pavilion to float independently, like a carousel in a fair.

Park: It is interesting to use kites that function only when there is wind, and I think it is a smart idea to create a public place that acts as a shadow at the same time.

Shen: The box kites take flight due to the wind that blows through its dimensions; equipped with flexibility, instability, dimension, and a translucent, light appearance, the kite has a strong connection with the site conditions. It brings a lightness to the structure, and creates playful shadows. In addition, the decision to use kites implies thinking on an individual scale, and after the exhibition, the three hundred kites that were used will become toys for children.

ⓒShawn Liu

Park: A pavilion is a functionally ambiguous, non-permanent building of various purposes, and I think the roles it can adopt within the city are so diverse. What activities can you actually discover in that space while also providing people with a shared space?

Shen: On site, we observed that there were parents and children, people that just sat there experiencing the wind, chatting, or reading. By not limiting the project to a clear purpose, and insisting upon a strict but persuasive scale, people that approach this project feel free and relaxed.

Park: The shape of the curved island under the canopy seems to welcome not only curved sides but the various shapes created by visitors. And there’s also a change to sound quality inside, what was the intention or process behind designing such content?

Shen: When planning open spaces, I always hope something will converge silently, calling forth a ‘lively peace’. The outside of the curved island provides a space for people to lean on, while the interior is like a bowl that gathers natural elements like the wind and sound.

ⓒStudioMillspace

Park: I’m also curious about your latest project, Sahne Elementary: Semi-outdoor Activity Space (2021). Semi-outdoor building in which people can shelter from the rain was added to the existing school. I felt it was important to establish a stylistic, formal, structural, and material relationship between the existing and new buildings.

Shen: The playground on the site is a source of creating connections. There are poinciana trees and recreational equipment that naturally draws children into the playground, so I wanted to extend this natural playfulness to the new activity space, as it should not only be used during classes, but also during recess. To create the ideal connection with its surroundings, I had to imagine architecture as a freeform, plastic boundary, interacting with the existing exterior elements, then enclosing it within a stable architecture mass.

Park: I think it is important to alter the surrounding relationships and the perception of users when a new building is built in an empty place. I feel like that this project reestablishes the existing surrounding order and spatial relationships with some simple suggestions.

Shen: Architecture indeed possesses the ability to create inner space, but at the same time it harbours the infinite potential to regulate exterior relationships. In my opinion, these two are not contradictory elements, and yet during the designing process we are often faced with contradictions. I do hope this activity space adopts a special orientation, which can also reestablish the existing surrounding order.

Park: As the layout is determined, tasks are divided into what is left on the ground, what needs to be erased, and what needs to be modified. That approach connects necessary development smoothly with existing buildings or contexts. What criteria did you use to decide what to leave, erase, or modify in the new space?

Shen: If the existing elements are encouraging of activities, I leave it be, or to even emphasise its essential properties. On the other hand, if it obstructs the flow of activities, it should be erased. Another essential reason is the view that we wish to see it from the inside.

ⓒStudioMillspace

Park: Is there a view that you considered important at the level of the existing building and the level of the new building?

Shen: A single viewpoint in this design does not exist as it is a multi-directional structure, and people will gradually discover new spaces while moving through them. The existing slope on the northern edge is a great activity space for children, so we were troubled by how the design could best respond to this slope. In the end we decided to create an even wider staircase, to connect the building with the columns, and to extend the existing slope for children so they could run freely through new and existing spaces.

Park: You have reduced the width of the eastern stairway and installed a wall. I would like to hear your thoughts on the separation between the parking lot and landscaped area.

Shen: The concrete walls on the southern edge were the earliest structures to appear. The initial outline was for the architecture to embrace the power of the land by penetrating the existing soil wall, and in addition creating an east-west connection. Coincidentally, the parking lot cannot be seen from the inside, leaving only the view of the mountains and the tips of the trees.

Park: The location of cantilever beams in the existing building and the structure of the newly built space has not been connected. Is the gap between structures considered separately?

Shen: The scale of the existing corridor and the newly built eaves almost overlap on the plan drawing but are separated by different heights. From a structural viewpoint, if an earthquake occurs, the new building will not affect the existing buildings. However, the independence of the new building is more significant to me, as I wanted them to differ in terms of personality but still communicate with one another.

Park: The difference in level across the cross-section of the existing building in the North is interesting. On the first floor, the space was planned to be flat, and on the balcony on the second floor, the interior of the new building could be seen, while the roof level was also planned with subtle changes. What was important about the connection between the existing buildings and playground levels?

Shen: Enabling people in the second-floor corridor on the west to look into the activity space and also the playground on the upper levels creates a dramatic relationship between different levels, and also bestows a flexibility of usage around the activity space. This further creates a connection of the senses across the entire schoolyard. My intention was for people to move through a transitional spaxe before entering the building. In addition, the design elements at each edge were an attempt to imitate existing structures, to extend space and devise an architectural language.

ⓒStudioMillspace