Tropical Space, led by Nguyễn Hải Long and Trần Thị Ngụ Ngôn, continue their work from their base in Hồ Chí Minh, southern Vietnam. They were introduced in issue 625 of SPACE through a focus on their interest in the history of Vietnamese architecture and more specifically in connection with their reinterpretation of the ‘Nhà ống’ that appeared during the French colonial period. Here, we hear more about how

they see their experimentation with changes to traditional houses in urban areas and consider new possibilities.

interview Nguyễn Hải Long, Trần Thị Ngụ Ngôn co-principals, Tropical Space × Park Changhyun principal, a round architects

Park Changhyun (Park): I’m curious about Vietnam’s slender urban house, known as the Nhà ống. The shape and layout of these narrow sites are common in many cities throughout Southeast Asia, which were colonised by Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but have disperese and developed differently depending on the characteristics of each city. I heard that the characteristics of the Nhà ống vary depending on when an example was created. Can you illuminate their differences? I wonder what the advantages and disadvantages of this form are in the urban setting?

Tropical Space (TS): The Nhà ống is a very distinctive type of house: a long and narrow tube-like shape. It is often found along main streets and alleyways. Initially, it appeared mainly on the streets near the canals or the river, where there are markets and various businesses. In the early days, the building was typically lower than it is now and was of deeper form in from the road. Some of them are more than 100m long, facing both the front and rear roads. There are mainly shops on the first floor, while roads, pedestrian routes, buyers, and sellers are close neighbours to create a bright and lively market space. The Nhà ống is narrow and long, with many inner gardens and spaces for each scale defined by different functions to reduce the overall span. The courtyard plays a role in creating layers in the space, attracting natural light into the rooms and allowing ease of ventilation. This architectural style is consistently applied throughout the street. It was economical and easy to use, especially in commercial districts, and it also played a large part in planning Vietnamese cities.

Park: According to the origin story of the Nhà ống there are many advantages, but how has it changed recently?

TS: As Vietnam becomes more of an urbanised country, the Nhà ống is also undergoing significant changes. Types of architecture are diversifying, with the length shortened to less than 10m or the height rising to seven stories, but on the other hand, this freedom can be confusing. Instead of following the principles of traditional spatial composition, it often focuses only on façades from the front and places air conditioners and lights without even a courtyard.

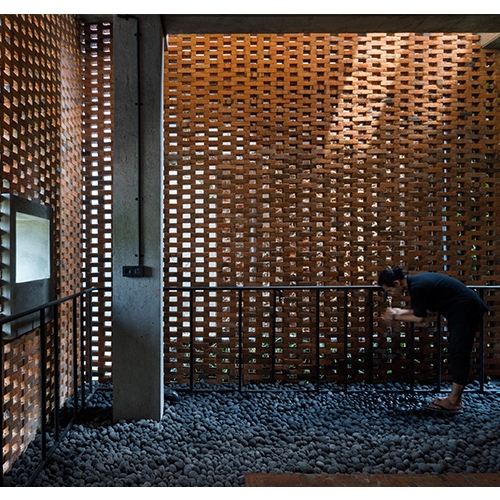

Tropical Space, Long An House, 2017

Park: Urbanisation is a problem that also affects Korea. Vietnam is currently actively concentrating on the city, but I wonder if the low density-oriented Nhà ống can co-exist with today’s social and contemporary needs? Or does it contradict them?

TS: Areas in which the Nhà ống are densely packed into the city fabric can cause problems such as busy sidewalks, traffic congestion, lack of green space or community playgrounds. It will also affect the health and quality of life of local people. In particular, the population of Vietnam is growing rapidly every year and the demand for housing is also increasing. Urbanisation occurs rapidly, and there are many difficulties in terms of the direction, coordination, administration, and operation of urban planning. However, we consider the Nhà ống to be one of the key features that we want to maintain in the city because we think they make the city more friendly and vibrant. However, in order to increase green space and leisure space in the region, it is also essential to control the density of the Nhà ống and to establish an appropriate urban design strategy that attends to quality of life and public health.

Park: Without the urban planning strategy currently under discussion, reckless urban development and sudden changes to urban spatial structure could also result in significant challenges to the daily lives of citizens?

TS: The trend for high-rise residences is inevitable, but I believe it is desirable in any urban context to hold several types of dwelling in balance, such as the Nhà ống, villas, and apartments, in order to meet social needs, economic growth, and consideration of urban and natural environments. A reasonable plan that takes into account individual homes, neighbourhoods, and even cities should be proposed to adjust density, designs suited for tropical climates, and also revitalise the city based around the Nhà ống. Architects need to study, practice and lead traditional housing in order to design good residential spaces. Traditional houses not only adapt well to local climate conditions, but they create comfortable interior spaces and reduce pressure on the external environment.

Park: What are some housing-related policies being advanced by the government?

TS: There is no clear housing policy in Vietnam at the present time. I don’t think the current choices and designs in urban planning are creative enough, particularly considering the complex relationship between nature, cities, buildings and people.

Park: If the rules are not clear at the national or urban level, attitudes to individual buildings will be important. Is there a space that Tropical Space thinks deserves particular attention in Vietnamese resi- dential architecture? From what I’ve seen of typical housing layouts and design so far, the composition of the spaces is similar to those found in Korea, such as the living room, kitchen, yard, and bedroom, but is there a more distinctive space in Vietnamese homes?

TS: As seen throughout Asian architecture, Vietnamese houses often have spaces for Buddha and the ancestors, usually located in the highest point in the house. As a consequence of the complexity and strong smell exuded by Vietnamese cuisine, the kitchen tends to be large and connected to an outdoor area. In the kitchen, especially in a large house or a house with a power source, there is a wet floor space. This is a place to wash ingredients when cooking at home or for preparing parties or meals for many people. Lastly, because Vietnamese people love nature very much, this space is also characterised by flowers, trees, gardening, and raising livestock and poultry.

Porous wall made of bamboo of traditional house in northern Vietnam ©Trieu Chien

Porous wall of Cuckoo House designed by Tropical Space

Park: What aspect of traditional Vietnamese residential architecture particularly interests Tropical Space?

TS: Vietnamese homes have different characteristics between the southern and northern regions—it is a very long country. The characteristics of traditional houses in northern Vietnam include a main room in the centre and additional rooms on both sides. The boundary line separating the interior and exterior spaces is ambiguous, and the tiled roof is low and long, casting shadows deep inside the house. This large sloping roof means the front porch area is less affected by rain and the sun, and, moreover, the porous wall structure allows wind and light to pass through. This is made of bamboo woven by the older generation and serves as the wall separating the space. These two factors are climate response methods adopted in traditional housing, which have changed in various ways, such as through thin curtains or light partitions with screens found in modern architecture.

Park: The aforementioned sloping roofs and spatial composition divided along from the centre and on both sides can also be found in your works of architecture. This is the case with Long An House (2017) with one floor above ground and one basement floor located in Đức Hòa, the rural district of Long An Province. When I read the plans, I found the symmetrical spatial composition and sequential arrangements, which are gradually arranged from public space to private space, impressive. The floor plan and narrative of the structure are look similar to that of your previous work, the Termitary House (2014).

TS: Our designs generally begin symmetrically, and the rules of order are softened by sunlight. Empty and full spaces are mixed proportionally with each other, and buffer spaces created in this process reduce any direct impact from the external environment. We usually embark upon the design phase by contemplating modules that have a sufficient bedroom and aisle area. In plan layouts, our spaces are designed to facilitate ventilation while avoiding rain and sunlight, specifically depending on the client’s way of life. In fact, this spatial composition has existed for a long time and is a method of deployment in harmony with nature and the environment. However, it seems that the lifestyle and technology have gradually disappeared due to modern changes.

Park: How do you expect symmetrical housing spaces to affect residents? It is also feared that this may produce a rather rigid experience because it is symmetrical in the spatial layout.

TS: I think the rich layers of inner and outer space, which are made of these symmetrical structures, allow people, trees, sunlight, materials, and walls to come together in one space, and these factors enrich the senses and experiences of residents. People define themselves through life experiences and the senses as much as through their ability to experience the world. Architecture is a catalyst of experience. Like all art, such as music and painting, architecture has a symmetrical structure, but it is very flexible and presents a variety of experiences.

Tropical Space, Long An House, 2017

Park: On the other hand, the building looks very closed off from the road. How was the boundary between the building and the surrounding area set? What is the role of a boundary in the Nhà ống? It is surely a very important physical expression, considering the relationship between neighbours and the space beyond the house itself?

TS: In high-density urban areas, the Nhà ống tends not to have fences. If there is a fence, it may have been temporarily built by residents to protect their homes so that their land will not be reclaimed due to future road expansion. On the other hand, fences are an essential means of securing safety, parking and landscaping areas and determining land boundaries in old urban areas or low-density residential areas. A fence can demarcate a social space of a house or a place to communicate with neighbours. A boundary is a matter between safety, privacy and social relations. In the old days, many generations lived together and formed communities, and the relationship between neighbours did not change much for centuries because they did not change much for centuries. The relationship of the community in the past was clear and stable. Most houses were divided by beautifully trimmed bushes, and some were able to communicate with those in the local area. Today society is developing, and much is changing as the movement from the provinces to the cities forms new residential communities. In this climate, people are not well aware of the meaning of living together, leading to conflict, envy, doubt, and security insecurity, which flows in a way very different to that of before. This has led to a change in the conception of boundaries and the development of a completely isolated and defensive attitude from the outside world. Instead of fences, we have trees inside and outside and various landscapes to induce connections with our neighbours.

Park: In that sense, Korea already has the same social problems, and architects are working together to improve them. The spatial composition of the Long An House is internally clear in terms of the functions of the rooms, but it looks like a space because it is not clearly opened and closed with walls or windows. Were there any difficulties in controlling each function? What architectural approaches have there been for blocking visual, auditory or olfactory contact?

TS: The clients are an elderly couple, who wanted as much privacy as they need. We tried to enact connectivity with the surroundings and necessary privacy through design. Private and closed spaces make it more difficult to relate, so I wanted to open more spaces up to draw traditional connections. Division between spaces was possible with the empty walls, light division, transitions between high and low spaces, and transitions between light and darkness. And considering the air circulation, the functional room is arranged to eliminate unwanted odors in the house. All bathrooms and kitchens are located in the open air.

Park: In your last issue of SPACE, I read the interview in which you said, ‘We aim to achieve various activities and create positive community relations through the “empty space” of the building’. Who can be said to be the ideal subject of this empty space?

TS: Both family members and local communities residing in the building are foremost in our minds. Living spaces with empty spaces help family members bond. The hollow wall structure also reduces the use of electrical equipment because it blocks heat, and reduces the impact on the external environment and local communities by creating space between them. I think living in a house full of positive energy will also be beneficial for family members to participate in local communities.

Tropical Space, Cuckoo House, 2019

Park: I would also like to ask about the empty space in the Cuckoo House (2019). The house, located in Đà Nẵng, is divided into the parents’ room and the children’s room based on the outer space on the second floor, and I wonder if the outer space serves well as the empty space you intended. How did you imagine the outer space of this house might differ from the empty space of Long An House?

TS: Empty spaces create relative distances so that attractive forces between spaces can be manifested. It also forms additional spaces between fixed spaces. Cuckoo House and Long An House have two different sites, requirements and uses. While the former is the house for a family of three children with an empty space for the children to vent their energy, the latter is the house for two elderly people, and the empty space at the centre is a place for concentration and self-reflection.

Park: How do you define the interior space and the exterior space? In the case of Long An House, there seems to be an intermediate area between functional spaces and so an empty space is naturally formed.

TS: The concepts inside and outside are relative. It depends on how the central object is selected. In the Long An house, the interior and exterior can be defined as relative spaces along the surface of the wall without being distinguished too overly according to the exact physical space. It can vary depending on the environment, past experiences and memories, and future potential. We only predict the possibility of multiple activities. This is how we create a relationship between relative space and interspace as well as boundaries with wind and sunlight.

Park: The Long An House, built of masonry, does not seem to have a water space inside the house. I think the experience of reversal will be intense, but what function does the water space have in this house?

TS: People are more interested when things don’t go according to logic or their assumptions. The unknown is always interesting, while functionally this water space lowers the temperature in the house.

Park: When I see pictures of the Long An House, I am able to visually experience various layers – like when one looks at plants, which are located in the inner space – through several walls in one space. I feel a sense of openness spatially and at the same time, as walls overlap with each other, I feel like spaces are gradually piling up.

TS: Layered spaces give the impression that trees are planted in layers. The architecture we create has many layers in its structure. These layered structures penetrate several layers, some are tightly blocked, others are empty, and become increasingly distinct and then fade. Here, people can face the sun’s light, and feel the wind and sound.

Assist in interview: Ju Han Seul (Korea University, Department of Architecture)

tropicalspaceil.com