Park Semi (Park): When I looked through the list of BARE¡¯s projects, I observed how different your projects are in terms of type, method, and orientation from those of other architectural firms. Over the course of about 20 exhibitions and research projects in the seven years since BARE¡¯s establishment in 2014, you have produced architectural meaning, blurring the boundaries between buildings (reality) and exhibitions (representation), unlike other architects who deal with display as supplementary. I would like to hear more about the background to the orientation in your work.

Jeon Jinhong (Jeon): We met each other in the Crossings Workshop at Hooke Park when we were studying at the AA School in the UK in 2006. Staying together there during the vacation, this workshop had been planned to make students create a new structure in the forest. What I found most interesting about this brief was that we had to do everything ourselves in order to realise something in a self-sufficient way, such as selecting the trees in the forest, cutting them, moving them, and installion. Rather than planning and executing everything in advance, we had to cope more immediately with situations in the field, examining conditions and actively drawing upon them. Throughout this process, I was able to keep exercising my imaginative faculties to create with my mind and think with my hands, and in this way, I think that it was no different from BARE¡¯s recent work – in that I think in an integrated way without separating design from making. What makes the Hooke Park workshop more meaningful to us is that by holding several exhibitions over three years since the first installation, we had the opportunity to observe the research materials documenting a series of processes be given new life as lively new projects. At first, the exhibition, which simply celebrated the award mainly through concepts and sketches, developed into a photography exhibition, showing the process behind the workshop and a group exhibition with models. Through this, I learned that the exhibition could have significant meaning independent of the original creation. This experience also served as the background to our recognition that exhibitions and installations, considered as creative works, produce architectural meaning and will continue to do so. While practicing separately after graduating, we agreed upon the necessity of a different way of thinking and a production system rather than privileging large-scale projects created in the flow of huge capital. So we decided to establish our own business.

Park: Your attitude to the integration of design and making is interesting. I would like to hear a little about how you deal with conflicting concepts such as the physical and the digital, the virtual and the real.

Choi Yunhee (Choi): The educational environment that I experienced encouraged me to handle various digital media for communication with skill, but at the same time prompted greater awareness of the threat of indulging in the latest gadgets. While I cut down trees and worked on installations in the woods, I had to perform script-based design through a computer programme when I returned to London. Although I was engaged in architectural practice for a large architectural firm, I also experienced a more collaborative environment formed of individuals from across various fields in the small studio of Jason Bruges, an artistic architect who works with interactive lighting. The studio had a workshop space that was spacious enough to make mock-ups, and the members included not only architects, but also designers, engineers, programmers, fabricators, all supported by a system that helped collaborative experiments as well as operation and installation on site.

Park: I think that you may use different media to convey a series of processes from research to installation to project, and you select materials to ensure your projects are visibly different from those achieved through conventional architectural methods.

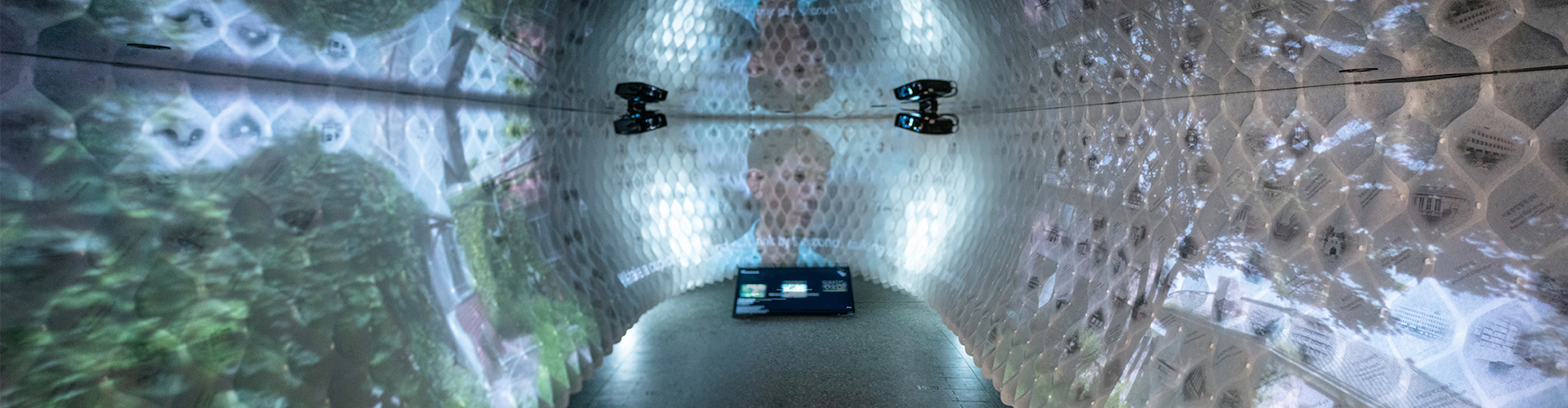

Jeon: I think people often take us for audiovisual producers. (laugh) While working on research-based projects, I tried to figure out how to most effectively deliver a large volume of information learnt throughout the process. We came to naturally select video as the most suitable medium. At the same time, we were interested in how images with digital properties could meet with structures with physical properties to become spatialised within a 3D image environment. In the case of the tunnel-like Dream Cell, presented at the ¡®New Perspectives on Architectural Assets¡¯ at the 2019 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, we wanted the exhibition to enable people to experience spaces of significant architectural value not usually accessible to the public. After trying to figure this out, we combined a 3D scanning technique and shooting with a 360-degree camera to allow visitors to experience stereoscopic images and structures. We try to find the optimal medium and communication methods under the given conditions.

Crossings Workshop is the result of collaborative works by students who voluntarily participated in from all units at AA school. Considered as the ancestor of AA Visiting School currently operating all over the world, the workshop was led by Valentin Bontjes van Beek and Nathalie Rozencwajg who won the Custerson Award in 2006. ©Crossings Workshop

Dream Cells ver.1, The 16th Venice Biennale Korean Pavilion ¡®Spectres of the State Avant-garde¡¯, 2018 ©Kim Kyoungtae

Dream Cells ver. beta, ¡®New Perspectives on Architectural Assets¡¯, The 2th Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, 2019 ©BARE

Park: I would like to understand how BARE produces, evolves, and implements its projects in greater detail. Dream Cell was first presented at the Architecture Exhibition in the Venice Biennale Korean Pavilion of 2018, and then subsequently at the homecoming exhibition of the Venice Biennale in 2019, an exhibition for the second Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, the 50th Anniversary Exhibition of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, and the ¡®Collecting Architecture for All¡¯ in 2020, and adapted on each occasion to the characteristics of each exhibition or exhibition hall. Please explain how you designed a work that was both site-specific and mutable at the same time.

Jeon: We used the first Korea Trade Fair (1968), a project hosted by Korea Engineering Consultants Corp. (KECC), as a reference point through which to examine the ways in which the Guro area has evolved over time. In the process, we interviewed individuals who were excluded from the perspective of the developing countries and those who had migrated for economic reasons in pursuit of their dreams, in order to capture a spectrum of voices. We tried to explore the possibility of continuing vitality in facilities that were prepared for the past exhibition by transposing them into new contexts rather than regarding them as temporary structures that disappear without leaving any trace after a certain period. Dream Cell is a white fabric structure designed as a modular structure that can be folded into a suitcase that represents the immigrants of Guro, which allows for the removal, transformation and expansion to adapt to new places. We call this possibility ¡®place-adaptiveness¡¯, and, conceving of the exhibition hall as a site we have tried to establish a complementary relationship in our works. For example, Dream Cell, installed in the exhibition hall of the Korean Pavilion which is transparently connected to the Giardini della Biennale in Venice, could not be presented in the same way as in the Arko Art Center in Seoul, which has a dark and low ceiling. Instead, we stuffed a curtain-type structure on the level 1 wall by archiving itself, and turned 180-degree upside down on level 2 and hung it on the ceiling to create a black mirror effect forming a hemisphere. In the Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture, we transformed it into a long tunnel in line with the long, narrow corridor space, and but in the massive circular exhibition room of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, we moved the black ceiling to create a mirror effect to the wall while retaining the shape of the intact dome. At the Seoul Museum of Art Nam-Seoul, which currently hosts the exhibition, one-twelveth of the work is on display along with a miniature model of the Venice Biennale version. In the process of changing the shape of Dream Cell, the faces and images on the screen also changed according to the content of the exhibition. Initially, the faces of the figures were presented only by laser engraving, but later, colour could be captured by using printable lamination.

Park: Looping City, an attempt to overlook the entire production process through the by-products discarded in the manufacturing process by shedding new light on the recycling industry in Euljiro area, and particularly Sewoon Plaza, was first presented at Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2017, followed by ¡®SHIFTING GROUND¡¯ in 2019, ¡®Contemporary Korean Architecture, Cosmopolitan Look 1989 – 2019¡¯, and TUBO 2020 recently. The project seemingly shows the strength of BARE¡¯s works in that its application has been extended to practices beyond the exhibition hall.

Choi: Looping City, a new recycling system based on local self-sufficiency, reflects our hopes that a new industrial infrastructure will build an alternative proposal to improve quality of life by connecting local industries with people. The new industrial infrastructure is TUBO, an unmanned mobile robot which collects and sorts the waste of various production lines; the TUBO Station, where these robots are charged and stored; and the Docking Station where collected by-products are processed as raw material for 3D printing. The first exhibition included just videos and drawings of observations and recordings of local area, but since then we have developed our approach thanks to invitations to overseas exhibitions. We finally presented TUBO as a mockumentary in 2019 by using 3D printing and a RC car body. Thanks to the help of the Sewoon Community, we managed this year to build up our size large enough to interact with people. The webpage for TUBO, which became smart enough to go around on its own to collect and sort recyclable items on the deck of Sewoon Plaza, will soon be available. Please watch and pay attention to TUBO.

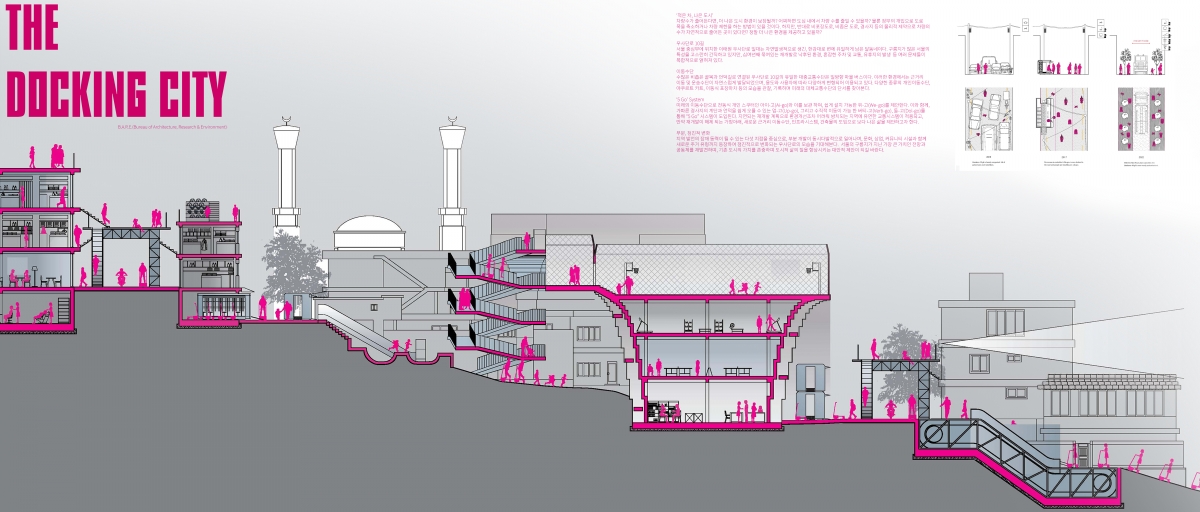

Park: Docking City is a project that proposes a future alternative form of transport by observing and recording the traffic and the transport of Usadan-ro 10-gil in Itaewon. Also beginning life as an exhibition, this project even proposed a working prototype that could be deployed in the field. It seems significant in that you have designed a system that can have commercial impact in a city beyond the simple design of a vehicular structure.

Jeon: Docking City is our first collaborative work that resulted from the Arumjigi Heritage Tomorrow Project in the Usadanro area of Itaewon, which has a mosque. ¡®Less Cars, Better City¡¯ was the theme, but of this we asked a question: ¡®Is our city going to be better if there are less cars around?¡¯ As we had a good understanding of this area based on two-years of research, we were able to develop an in-depth project with Minsuk Cho (principal, Mass Studies) and Park Kyung (professor, UCSD), who were members of the jury during the competition period held as a six-month workshop. From a private scooter to a system for storing and return, Ai-go was proposed in stages from the perspective of social infrastructure. It was a strategy to respect the existing topography and strengthen local self-sufficiency in spite of cancelled development planning. We produced a working prototype and brought it to the site so that local people could have a trial ride, and we also imagined a different future with them. The charm of our job is that we can imagine with many other people. This is often the driving force behind our work, to present something and make it work. Most of all, it helps us find the gap between public and private sector in our society, and anticipates the potential of an architect who take the role of the medium and intervene in the situation.

Section of Docking City ©BARE

TUBO 2020, Looping City ver. 3, To be installed on the Sewoon Walking Deck and will be released online, 2020 ©Bae Hansol

Park: Tracing the Plan is also an interesting project, which was introduced in ¡®Contemporary Korean Architecture, Cosmopolitan Look 1989 – 2019¡¯. It is a digital book that responds sensitively to the movements of our body. It is refreshing to find that architects can design such small objects. What does the design of objects mean in terms of architecture?

Choi: Installed on the wall of the exhibition entrance, Tracing the Plan is a digital book that shows different images on round screen according to the speed of a sliding bar controlled by the audience. I wanted to help the overseas audience understand the context of the exhibition more intuitively by scrolling the content on this round screen. Audience participation always plays an important role in our work, and we try to expand upon the possible breadth of communication by inducing a sensuous experience rather than simple visual appreciation.

Jeon: When we planned this exhibition, we had to take a more flexible approach in anticipation of some changes to content as we were considering the possibility of a touring exhibition and its expansion as an architectural platform in East Asia. Seen from the viewpoint of things, architecture naturally leads us to raise the question again about so-called life cycle of a building: construction with a fixed form and function, demolition after a certain period, and ultimately reconstruction. We would like to continue our exploration of architecture in which space accommodates rapidly changing situations through objects combined with digital technology. Now, we are focusing on what lies between furniture and a building.

Park: What do you think marks out the difference between industrial designers, developers, and even artists when architects carry out their design work from the perspective of things?

Choi: While artists present their own themes and stories in an exhibition, we usually make suggestions based on context or conditions, which seems the influence of architectural education. When we ask questions as artists and try to solve problems as designers, we find we can create imaginative works based on our research. Although the classification of by-products as in Looping City is not appropriate in terms of economic logic, thinking from the perspective of intelligent things leads to a completely different way of thinking. We need to understand that things occupy a city or building space just as people do, but they have different behaviour patterns. Moreover, when we design a space that is to be reorganised around those objects, we will inevitably require a different approach.

Park: One can¡¯t keep carrying out their work without considering the issue of survival. Architects are paid for their designs. To ask the question a little coarsely, how does BARE mean to survive? This question could be rephased as follows; ¡®How large is the Korean architecture exhibition market?¡¯ And moreover, what role do art galleries or exhibitions play for the architects of today?

Jeon: Contributing in some way to the expansion of the art world by challenging the typical white cube exhibition spaces, and closing the distance between the audience and society, architectural exhibitions flourish in the art system. Many, such as those at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, have established themselves as a new genre in contemporary art. In addition, architectural biennales from around the world, including the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, treat the host city as a testing ground and the subject of broader discourse, and have produced a huge amount of research, policy proposals and provided opportunities for architecture to intercede in various urgent urban and social issues. Such quantitative expansion in the 2010s elevated the importance of expert architectural planning in the field of architectural criticism, across history, theory and publication, and the role to be plated by professional architectural curators and architectural institutions to manage and study architectural collections. In particular, we are looking forward to future discussions about collecting products from the exhibition and the archival system in terms of the formation of a new ecosystem for architectural and cultural industry in conjunction with the construction of the Korean Museum of Urbanism and Architecture scheduled in 2025. We participated in all commissioned work, including architectural exhibitions, urban research, and public art, which amplifies the experience and maturity of architectural exhibitions in Korea. Thankfully, we managed to complete all of them thanks to the help of our collaborators and those striving to create a healthy architectural culture, all of which has produced valuable experiences different from any other architectural exhibitions that are often considered to be exhausting.

Park: BARE¡¯s architectural practice calls to mind some grandiose questions. Do you think it is time to redefine the scope of the function of the architect? Or does this practice make architects return to their proper function? Or is the title of architect itself meaningless?

Choi: I think these issues are to extensive to answer with our limited experience. I hope it is still meaningful to say that this interview has provided an opportunity to share such thoughts. What we can say here, however, is that since the establishment of our own business in the early thirties, we have constantly challenged ¡®what we can do now and what we won¡¯t be able to do later¡¯ from a sense of desperation rather than a grand plan. As the name BARE (Bureau of Architecture, Research & Environment) implies, through a focus on architecture, we will continue to practice and implement architecture that can capture the various ¡®wishes¡¯ of the public founded on our firm conviction that research is vital, as is consideration of its impact on the environment.

Tracing the Plan, ¡®Korean Contemporary Architecture Cosmopolitan Look 1989 – 2019¡¯ ©László Mudra