So Dongho’s works don’t seem to have a uniform formal language. Living objects ranging from lighting, chairs, tables, storage furniture, magnets to posters, and are all the result of different approaches and processes. He sets the starting points of his designs not at the function but at the selected material and technique. Although he has presented work with a strong Korean identity, the definition ‘vernacular design’ is not enough to explain the character of his work. Combining natural and industrial materials, traditional craft and machining techniques at the right moment to create works of both familiar and unfamiliar impressions. As head of ‘studio sodongho’ in Sallim-dong, Euljiro, he is now working as an independent designer.

So Dongho, Ban-sang lamp, ash, Korean lacquer, 27×16×40cm, 2013 (©So Dongho)

Interview So Dongho × Choi Eunhwa

Choi Eunhwa (Choi): At first, you presented work that focused primarily on traditional craft. Is tradition the crucial basis of your works?

So Dongho (So): Much of my work is inspired by the techniques, materials, and images of Korean traditional craft, and I have participated in workshops and chased local artisans to learn the particulars of various traditional crafts. I have done so to employ the diverse attributes of traditional crafts as my design sources rather than mastering tradition as a craftsman. I believe I can establish my own identity while combining a sense of both tradition and modern design, and I hope I can have in-depth discussions when I collaborate with artisans.

Choi: What is your particular motivation for reinterpreting tradition and integrating it within your own design?

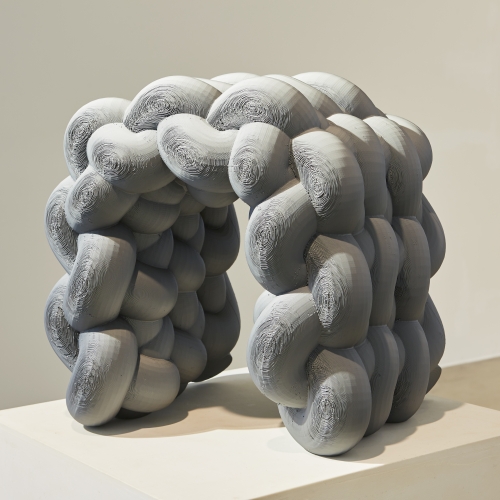

So: While craftsmen typically concentrate on the specific material or technique, I enjoy a variety of attempts in order to imagine what kind of effect could be created when a specific material is combined with a new technique. In the Origami series, the pendant and lighting of a geometric volume have been created by folding traditional Korean paper, and the Ban-sang lamp, a table stand lamp, has been made by reconstructing a rice bowl, soup bowl, spoon and chopsticks on a Korean lacquered table for one person. Works such as the Nak-dong series drew upon the Nakdong technique, burning the surface of paulownia wood to give a dark colour and hardness when lacquering in making tables, partitions, and chairs. While I work, I try to figure out which technique best display the characteristics of the chosen material, which effect could be made by using materials with contrasting natures, and what kind of harmony could be achieved by combining materials, techniques, and forms.

Choi: Since opening ‘studio sodongho’ in Euljiro, you have used more materials than ever before. Your selection of industrial materials such as brass, iron and plastic is remarkable.

So: In Euljiro, the starting point of any one work is usually the technique. A walk around Euljiro will reveal to you that there are so many techniques. One of them is Sibori. Once I find one technique, I try to figure out the exact definition of the technique, why the metalworking specialists don’t adopt the technique, what materials the technique can be applied to, and what form it can take, and so on. This led to the creation of lightings Sibori series. There are a lot of vague industrial terms such as ‘Sibori’ and ‘Pau’. Until now, Japanese terms from Japanese colonial period have been used. I could satisfy my curiosity as I summarized those words like dictionary definition.

Choi: You seem to have a special affection for Euljiro.

So: I have had a sustained affection and interest in Euljiro. At first, I tried to figure out how to use the abundance of materials and techniques. Now, however, I have come to think about even what I can do in Euljiro. Nowadays, Euljiro is abuzz with redevelopment. My favourite pub, Eulji OB Bear, also escaped closure, and I cooperated with acquaintances to create a performance work communicated through my personal social media platforms.

Choi: What do you think is the most Euljiro work?

So: My room could only really be realised in Euljiro. At the request of the Junggu Office, I installed a landscape lighting fixture on the exterior wall of a building to symbolically express the specialized Euljiro lighting street. With the hope of realising the coziness of a dark room by using only one lightning fixture in a city corner, I made the simplest work of lighting on a huge scale. I wished to produce it in Euljiro but I couldn’t find a workshop large enough to handle an object over 3m, which meant I had to manufacture in Paju and bring it to Euljiro. In fact, I was worried at first as I had never done anything bigger than my own height, but if I don’t have my own building, how can I attempt objects on such a scale? Although I had many difficulties, from finding installers to considering the potential risk factors of the lighting to the building and the street, I managed to complete the project with a great deal of support from others.

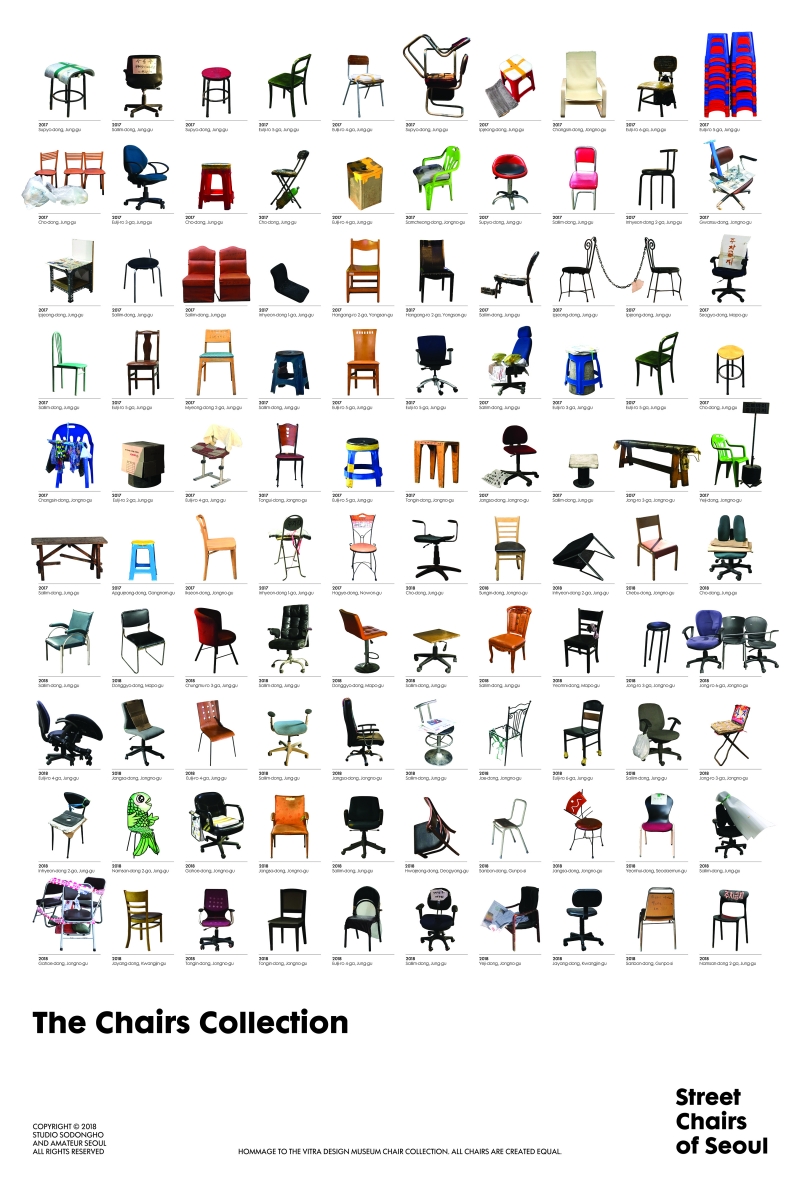

Choi: Street Chairs of Seoul is interesting that you yourself are a furniture designer but that you chose to draw a line between the chairs out on the streets to the archive instead of designing your own.

So: I took pictures of chairs I found on the streets from 2017 to 2018. Unlike that of ready-made products, it was interesting to find that some elements had been removed or added to the chairs, depending on who used them and where they were placed. As this archive began to increase, I decided to create a poster showing 100 chairs at once, as an homage to the Chair Collection Poster at the Vitra Design Museum. Seeing the poster from a distance, quite a few people take it for the Vitra’s own, as it is in the same format. A closer look however proves that they are not quality chairs made by European modern designers, but contemporary ones in the streets of Seoul. The contrast of these two contradictory branches is enjoyable. My final goal for Street Chairs of Seoul is to collect 224 street chairs and produce a larger version of the poster, as in the Vitra posters. I am planning to complete it next year.

Choi: You are extending your scope of observation from Euljiro and Seoul to the whole of Korea. I would like to know more about the background to Pojangmacha Seoul, with its theme of the orange coloured cart bar that can be easily observed on the streets in Korea.

So: I think one of the most unique identifying characteristics of Seoul and South Korea is pojangmacha, the cart bar. When you meet it in a dark alley you may experience a warm atmosphere, as if one as left just one light on. With love for this feeling, I made a scaled-down lighting fixture in the shape of the cart bar. I also produced shoulder bags with the cart bar covering. Some say that they remind them of the Freitag bags made of recycled truck waterproofing material, but they are not made of this real covering used for cart bars. I used the same material to show how the identity can fully embrace local culture. I also worked with graphic designers on the booklet, featuring the images and stories of pojangmacha.

Choi: I would like to hear about your future plans.

So: These days, I am committed to more projects related to exhibitions and planning as opposed to strict design work. I am participating in the Euljiro Light Way this October and the Seoul Design Festival this December as the Art Director.

So Dongho, Sibori series, copper, Korean lacquer, Ø31×20cm, 2016 – 2017

So Dongho, Nak-dong series, Korean burnt paulownia, Chinese mahogany, Korean lacquer, 44×44×80cm (chair), 50×30×49cm (tables), 68×33×160cm (partition), 2015

So Dongho, Pojangmacha Seoul, tarpaulin, tarp sheet, paper, 35×27cm (bag), 148×210mm (booklet), 40×20×21cm (lamp), 2016

So Dongho, Street Chairs of Seoul, poster, 610×915mm, 2018 (©So Dongho)

www.sodongho.com