One’s desire to get closer to the natural environment and the public demand to enhance the conditions of urban life have given rise to artificial nature in the city. The desire for natural space within the urban context has never diminished. Regrettably, this artificial nature rarely settles within the city structure, and often ends up dependent upon other urban facilities.

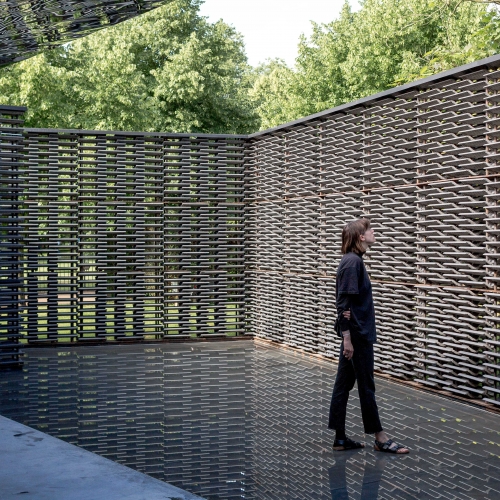

Every year, the Serpentine Gallery invites architects whose work has never been realised within the UK to Hyde Park and offers their front lawn to them. The recipients strive towards a new sensibility through mounting several spatial experiments, pushing the envelope beyond that of a simple architectural message. The pavilion is packed with guests every summer, members of the public who are keen to experience a new spatial experiment; therefore it becomes a kind of contemporary museum. The presence of the park is little affected as just another urban amenity, and the pavilion inevitably sits as a good object.

©Norbert Tukaj

This year, Serpentine Gallery invited Junya Ishigami to design the temporary pavilion. Ishigami pursues architecture as a part of landscape instead of as an independent building. He argues for architecture as landscape, not as an independent object. This issue has always been uttered in’s and around his projects. For example, the Kanagawa Institute of Technology’s KAIT Workshop (2008), his first architectural project, is set between nature and architecture, like a forest without a circulating promenade. That made me even more intrigued to see how he would manage to design a pavilion in the park out of an artificially created landscape. My sense was that if the pavilion succeeded as a natural space within this scenery, then the park must have grown into a new type of natural space set apart from the urban context.

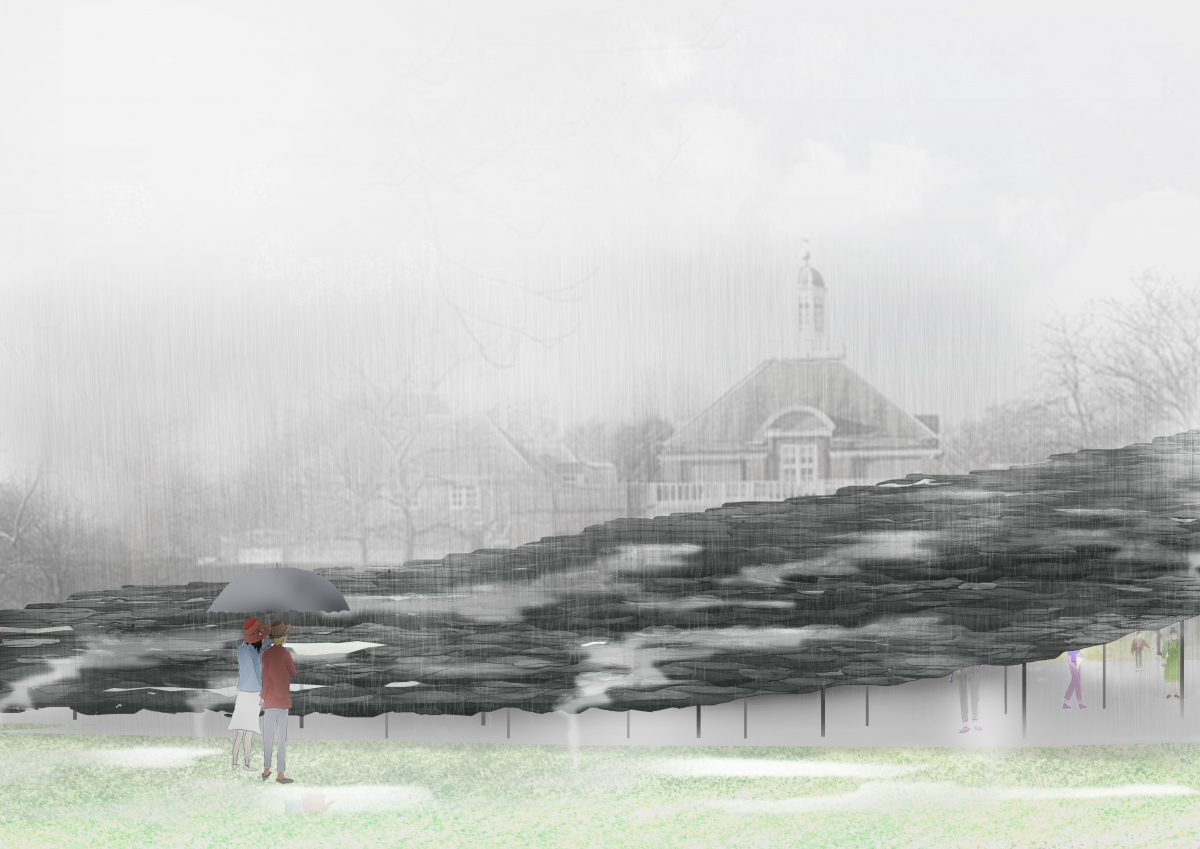

The image of the collage worked by Ishigami reveals a pile of stones wet and black in the drizzling rain. This abstract image, without details of materials or construction methodology, portrays two people holding an umbrella in the rain, staring blankly at the pavilion. However, it was a clear day when the talk between Hans Ulrich Obrist (artistic director, Serpentine Gallery) and Ishigami was held. Waterproof membranes between stones and the steel frame were emboldened in the clear sky. Obrist mentioned the very collage that I had in mind: ‘We need a collage which paves the way to a different perspective rather than presenting a regular one’, suggested Ishigami. His remark highlights the importance of image in materialising his imagination. His saying ‘I pictured the rainy day’ reveals to us that the black of the pavilion when wet was a scene he desired. The abstract collage depicting the image of the stone roof in the rain allows visitors to relax within their own aesthetic appreciation just as they can experience varied emotional moments in a dense forest.

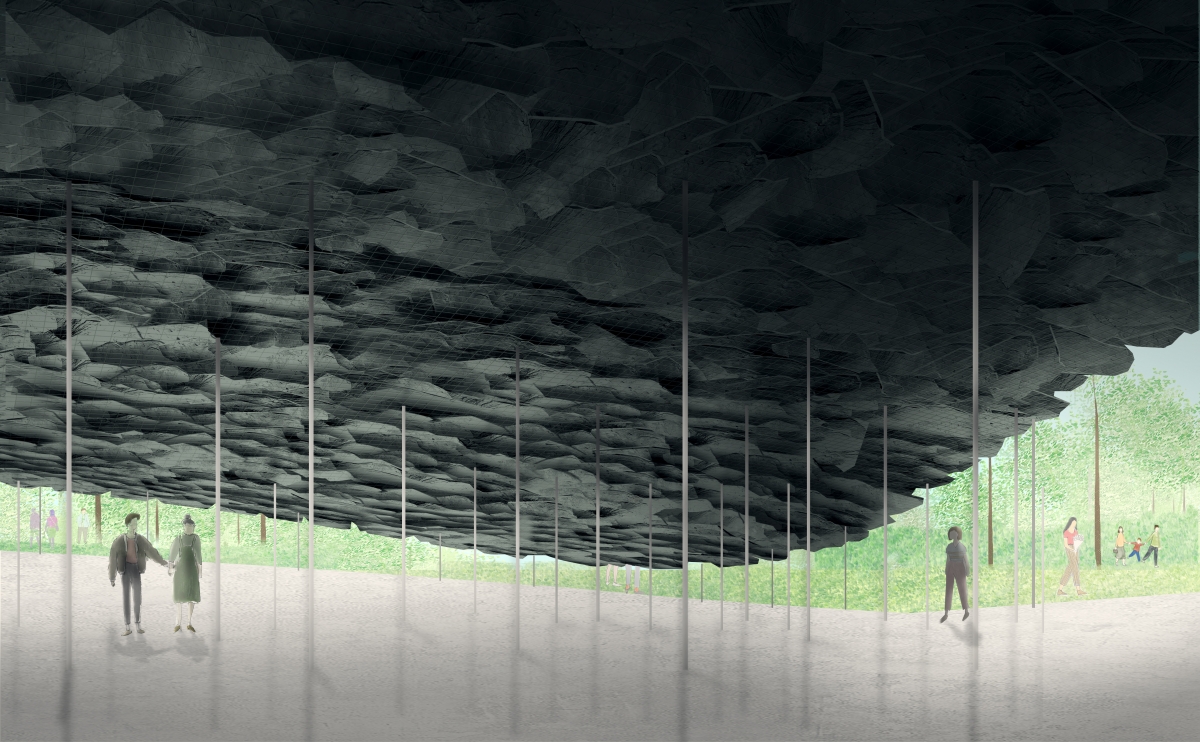

The cave-like interior reveals the objective facts of the materials and its construction by making the dark stone-clads and thin columns that support the roof visible. Ishigami noted that ‘A stone creates a landscape, and a landscape usually sits outside of a building. I wanted to create a landscape inside the building’. However, can a pile of stones change the overall atmosphere of the park? What about the surrounding space of the park that remains untouched by the pavilion? Maybe we can simply blame this separation on the necessary size of pavilion. As soon as we perceive the entire structure in one glimpse, we regard it as an individual object. The moment the pavilion is reduced to an individual object, the park automatically reverts to galleries.

©Junya Ishigami + Associates

©Junya Ishigami + Associates

In the past, Ishigami has worked on distorting the proportions of scale, such as width, height, thickness and length. Projects such as Chapel of Valley (2017), a chapel with a 1.3m width by 45m height, and University Multipurpose Hall (2016), with a 100m hall enclosed with 10mm material, frankly delivers a hope: ‘I wish to think freely; far beyond the simple stereotypes that restrict what architecture is considered to be’.▼1 His work is performed on a free scale whilst maintaining an extreme precision in dealing with his materials and construction methods. However, the pavilion seems rather ordinary in terms of materials and construction compared to his previous works, and its perimeter can be grasped at a glance. There is a lack of wow-factors derived from distorted scales. The absence hints to us that he was focusing on other areas, leaving us with the question ‘why?’, rather than ‘how?’

Explaining why he chose stone as his main material, Ishigami reflected, ‘I found that ancient buildings from across the world share certain similarities. You can observe stone roofs in Japan, China and Europe. So I started to focus on those ancient techniques that have that universality’. In addition, he explained that he ‘decided to use stone to make this building and when I thought about the context of the Serpentine site I decided on slate. This decision was also made because it is a readily available British material’. The material in the stone roof, Cumbrian slate, which is widely used in the UK, and the most basic method of construction is layered over. His pursuit of universality conjures a sense of the ‘as found’ conceived by Alison and Peter Smithson, but Ishigami seeks universal materials to extend the everyday environment of park landscapes, and not to enact new discoveries or values in everyday life. This reconfirms that his focus was on the landscape created by architecture. His resolute attitude resonates with his words that ‘I want to make buildings look old as if they had already been’.

It is less convincing to claim that architecture has turned into a kind of scenic design by pursuing universality. Instead, we need to pay attention to scenery in that it is always a relationship with the surroundings. Ishigami and his team have proved that they are capable of converting the surroundings. A 3mm-thick-table featured in Kirin Art Project (2005) generates a sensation of weightlessness by its overwhelming 9m length, and a structure of 0.9mm carbon fiber at the Venice Biennale, architecture as air (2010) left people visually dazed when roaming between the object and the background. What kind of sensibility did he want to twist in his Hyde Park project?

The stone-cladding ‘possesses the weighty presence of slate roofs observed around the world, and simultaneously appears so light that it could blow away in the breeze. The cluster of scattered rock levitates, like a billowing piece of fabric’.▼2 Ishigami added, ‘it can make a stronger surface because it is made of small-sized stones’, brushing off of the outmoded concept that ‘stone is heavy’. Layers of thin, black stones, as the architect put it, stimulate our senses as they surrounds us with shimmering lightness. Shedding new light on the concept of weight, he envisions that the ‘expanse of the scenery’▼3, completed by the atypical pavilion, will refresh the park’s atmosphere. It sometimes becomes ‘a blackbird’▼4 flying in the sky as well as a cave that opens out of the earth. It reshapes the park by belonging with varied perspectives.

The moment we look at the pavilion as a part

of the scenery, his magic twists our senses

once again. It restores our basic senses,

allowing us to realise that it is no longer an

urban space while transitioning from city to

park and park to natural scenery. The pile

of stones, which seems to have taken off

from mother earth, reveals itself as if it has

always been there. If his past works are like

acupuncture, delving into the depths with

extreme precision, the pile of stones is a

work of psychotherapy that extends infinitely

to the surroundings. For even a huge park is

reinvented as a new environment for itself, not as mimicry of nature. The scene from

the inside is no longer dependent on the

city. The Pavilion, which has become its

own unique scenery, functions in the milieu

of a context. Unless the scenery inside

is separated from its surroundings, the

Pavilion is no longer an object belonging

to the museum. This pile of rocks is more

than a simple shelter and exists as a part of

landscape.

1. Foundation Cartier website [www.fondationcartier.com/en/exhibitions/junya-ishigami]

2. Serpentine Galley website [www.serpentinegalleries.org]

3. Ibid.

4. Sebastian Jordahn, ‘Serpentine Pavilion designed to be “part of surrounding landscape” says Junya Ishigami’, Dezeen, 2019.

©Norbert Tukaj

©Taran Wilkhu

©Iwan Baan