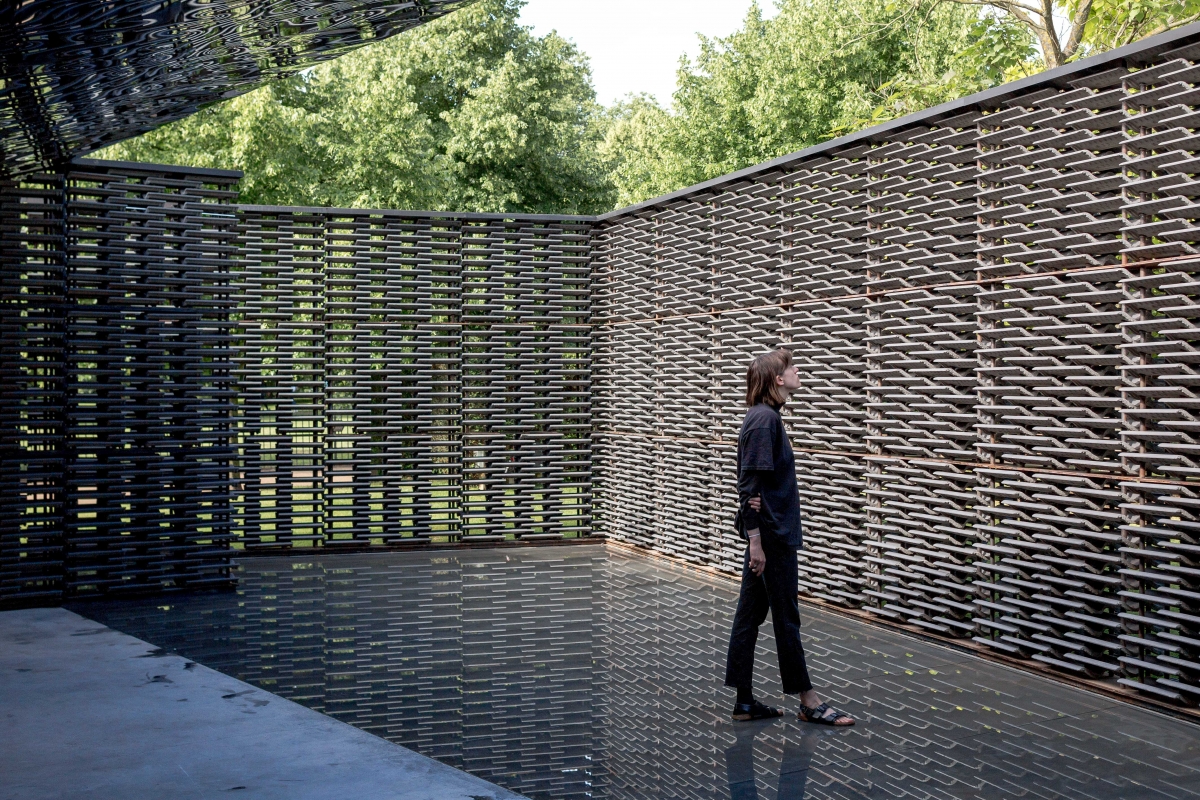

Walking up West Carriage Drive towards London’s Serpentine Gallery, bordered by the lawns of Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, I see a dark grey wall rising like a mirage above the green horizon. From this distance two façades are bristling with the heat of this July day, sunlight glinting through thousands of small openings. There’s a rippling effect to the surface of this wall, an unreality that becomes more solid and palpable as I draw closer. An enclosure that seems to breathe into its surroundings through these multiple perforations nevertheless almost completely obscures what takes place inside. Those already inside the structure are seen only as shadows, creating shifting, spectral impressions from behind the walls.

Frida Escobedo, the architect behind this year’s elegant pavilion, is only the second solo woman architect to be chosen to design a temporary pavilion on the Serpentine Gallery lawn in Kensington Gardens, London, preceded by Zaha Hadid who designed the first Serpentine Gallery Pavilion (hereinafter Serpentine Pavilion) in 2000. Born in 1979 in Mexico City, she is also the youngest architect to accept the invitation for this prestigious annual commission. Serpentine Galleries artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist and CEO Yana Peel selected Escobedo, with advisors David Adjaye and Richard Rogers, and their selection is a reflection of the Serpentine’s efforts in recent years to place greater emphasis on new, dynamic architects from around the world, such as Smiljan Radic and Diébédo Francis Kéré. Escobedo studied architecture at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City before completing a master’s degree in public art at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, and has written of how her work seeks to explore the relationship between art and architecture. Adhering to Kersten Geers’ advice, to ‘stay slippery’, the active blurring of boundaries across her practice is the way she achieves her singular vision. This woven perimeter wall turns out to be a series of interconnected porous partitions that encase a concrete courtyard, mirrored ceiling and shallow pool. Two rectangular volumes have been placed at an angle against the central courtyard: ‘it’s a compression and an expansion, and then a compression again’, Escobedo explains. The outer walls align with the Serpentine Gallery’s eastern façade, but the axis of the internal courtyard is oriented directly to the north. The courtyard is a popular feature of Mexican residential architecture, which is of course also familiar to Korean homes in the form of the Hanok. Effort has been made to make this courtyard a place of repose and contemplation, with delicate black folding chairs and tables spread across the concrete floor. As I entered I saw visitors teetering at the edge of the narrow, shallow pool at the far end of the space, as if eager to step a little way in and cool their feet. The space is full of reflections. A mirrored ceiling arches over the courtyard and ends at the line of the pool below, allowing the sky to be reflected in the sheer surface of the water. People cluster to look up at themselves in the curved mirror plates, which have been dented throughout with slight circular depressions. This effect distorts the reflections, warping the stacked tiles into whorls of shimmering grey, the chairs and tables below into inverted spidery lines, the bodies of visitors into fantastical convulsions. Even the natural wear of the concrete floor takes on otherworldly wavelengths, its marks and abrasions blurring above with each step.

‘I think I’ve always been fascinated by the relationship between interior and exterior’, Escobedo noted in a recent interview. ‘I grew up in an apartment that looked out on other apartments. I was an only child for a long time, so my entertainment was to look out the window… The apartments had the same structure on the outside, but on the inside they were all different’. Observing the lives lived all around her from this vantage point, she developed a keen eye and a curiosity for the individual amidst the vast urban network. Each of the many windows offered a tiny glimpse into a unique moment of a life lived in the city, all of which existed in proximity to her own life, space and time. Memories of details such as the peculiar ornaments or vivid colours that furnished certain of these spaces stayed with her from childhood, presumably going on to inspire the hive-like energy of many of her building façades. ‘In Mexico we have this constant juxtaposition of layers’ she notes, ‘and that has informed a lot of my practice. It’s a way of understanding time and space.’ Intriguingly, one of the operative values of the space, the north-facing courtyard, was guided by the site’s proximity to the Greenwich Meridian Line, the line from which all international time zones are measured. ‘We remembered that the Greenwich Meridian is just a few miles away from here’, Escobedo explains, and inspired by this notion, ‘this idea of abstract time, of social time, of scientific time versus social time or duration’, she decided to orient the space in salutation to this line. ‘This very subtle shift allowed us to make this small gesture towards an abstraction of what time is. This alignment is highlighted by the ceiling, it’s directed in parallel to the Greenwich Meridian and it allows the sun to go through the pavilion in that specific direction so you can actually see the passing of the day.’ Knowledge of this design decision throws new light on how visitors see their time within the space, a shelter that acts as its own timekeeper. Lines typically drawn between binary oppositions such as light and dark, rough and smooth, open and closed, certainty and doubt, real and unreal, all seem to blur into indistinction in this illusory pavilion, abstractions that have little relevance inside its walls, much like time itself.

One aspect of the architecture of her native Mexico City has proven to be pivotal for this year’s pavilion. Escobedo has taken inspiration from the celosia—a traditional breeze wall very common in the residential architecture of Mexico City. These walls or screens are typically latticework breezewalls that are incorporated into structures to moderate the intensity of Mexico’s sunlight hours, allowing enough light and air into the home in a filtered way but also the shelter of shade and the promise of privacy. The undulating patterning across the walls of Escobedo’s pavilion is like a tapestry made from stacked cement roofing tiles threaded onto steel poles, standing dozens high. As the result of Escobedo’s commitment to sourcing local materials in her projects, the tiles were sourced from a local British company and chosen for their rich grey colouring and textured surface. The effect is of small, simple fragments building a powerful, sophisticated whole. As Escobedo explains, ‘we’re creating this pattern that allows us to create a lattice instead of a wall that has different degrees of transparency depending on whether the light is hitting it on the front or in the back so it becomes more translucent or more opaque as the day comes through.’ Like the shutter of a camera lens, each of these small openings appear to open and close as you walk past, blinking in the sunlight. From the outside, bodies ripple across your line of sight, while from inside looking out all is the dappled blue and green of the park. ‘It’s more about these little frames, it’s more like a montage of spaces that happen, one right next to the other’, Escobedo has said of her design. I don’t think Escobedo means for her projects to be read as cinematic, but rather that they are experienced, in all of their intricacy and detail, as momentary spectacles readily committed to dream and to memory.

Since setting up her eponymous firm in 2006, she has explored the potential of screens and latticework in other projects. In 2010 she partnered on renovations to the Hotel Boca Chica in Acapulco, updating its chic white lattice brickwork, and in the same year, as her first solo project, she created the El Eco Pavilion in Mexico City, a site-specific installation of stacks of pale concrete blocks that could be moved and reorganised by visitors to accommodate talks, gatherings, or performances. In 2014, Escobedo transformed the former home and studio of the Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros into a public gallery, La Tallera in Cuernavaca, by encasing the complex of buildings within perforated concrete walls. The wall grouped the buildings together, extending around the perimeter of the site originally built in the 1960s, but also allowed daylight to penetrate the spaces within, illuminating the exhibition rooms, workshop, and artists’ residency. Her intervention on the campus of the Stanford Graduate Business School, completed in 2016, took a more playful approach, devising a russet-coloured Solanum steel screen that can create melodies. Inspired by the sound patterns achieved by children as they trail sticks along metal fences, ‘A Very Short Space of Time Through Very Short Times of Space’ is an interactive structure that is as visually impressive as it is conceptually engaging. Sounds can be produced as one passes by, by moving alternate closed fragments of one’s choosing. However, there is no one unifying style in her projects to date, and this desire to constantly adapt and find new inspiration at the human level of both material and experience is testament to her agile design intelligence. ‘Architecture is always the ruin of its own idea’, Escobedo has said, and in an era of perfectability this is refreshing, as it speaks to the architects ultimate lack of control once the pen leaves the drawing board or the final brick is placed. Escobedo is more interested in the operative value of a space, of the ways that it might empower, prove adaptable, shift expectations, uncover truths and inspire. In a recent interview with the magazine The Fabulist, Escobedo spoke of her passion for adaptability and flexibility in architecture faced with the possibility of natural disasters, such as the 2017 earthquake in Mexico: ‘I think one needs to plan for change. Make everything more flexible in every way, so that the building becomes more like a palm tree and less like a completely rigid structure, because that’s the one that will fall down. Rigid things collapse. The rest can move, yes, it transforms, it may lose sections, but its spirit will remain.’

Of course, the nature of the Serpentine Pavilion commission is that it is for a temporary structure. I hope the spirit of this project will remain long after it departs for other climes. This serene, humane and ruminative space is a welcome refuge from one of the busiest parts of the city. Escobedo has crafted a highly sensitive space, attuned to the imaginations of those who enter. Within its walls time warps along with the play of reflections, and through all of us the line is redrawn.

Frida Escobedo’s Serpentine pavilion is at the Serpentine Gallery, London, from 15 June to 7 October.