SPACE July 2025 (No. 692)

Rapid population decline is shaking the fabric of small and medium-sized cities to the core. To rebuild these cities, we need to move away from the inertia of regeneration and take a perspective that acknowledging change. This is where the Mid-Size City Forum comes in. They look at phenomena outside the metropolitan area and seek urban and architectural alternatives to the crisis.

[Series] The Possibilities Inherent in Extinction, Mid-Size City Forum

01 What is Happening Outside the Metropolitan Area

02 Thinning Phenomenon

03 Urban Perforation

04 Erasing Plan

05 Ad-Hoc Architecture 1

06 Ad-Hoc Architecture 2

07 Global Mid-Size City

08 Temporary Mid-Size City

09 Mutation of Facilities 1

10 Mutation of Facilities 2

11 Outside the Mid-Size City

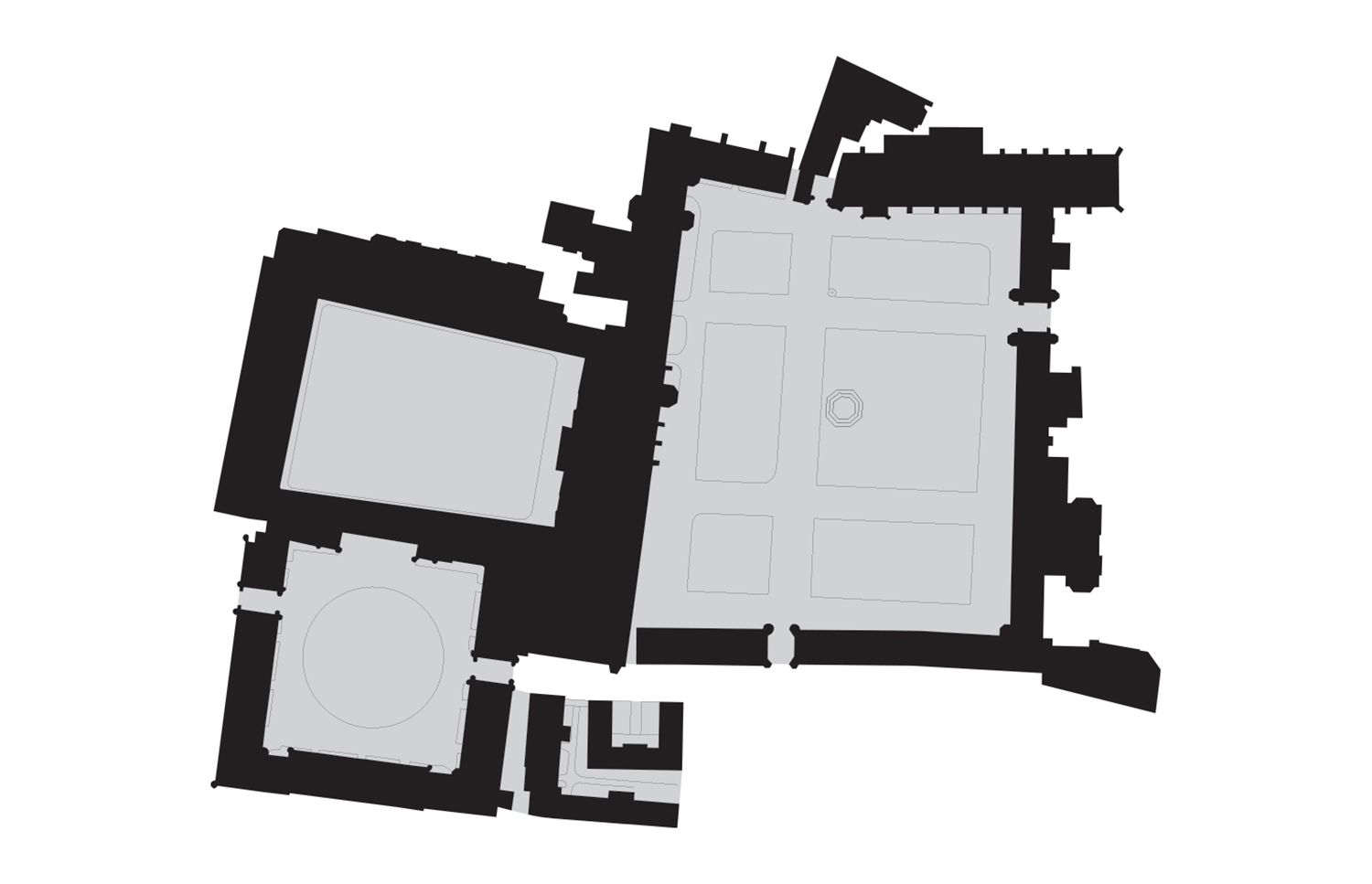

The quadrangle of Trinity College, Cambridge

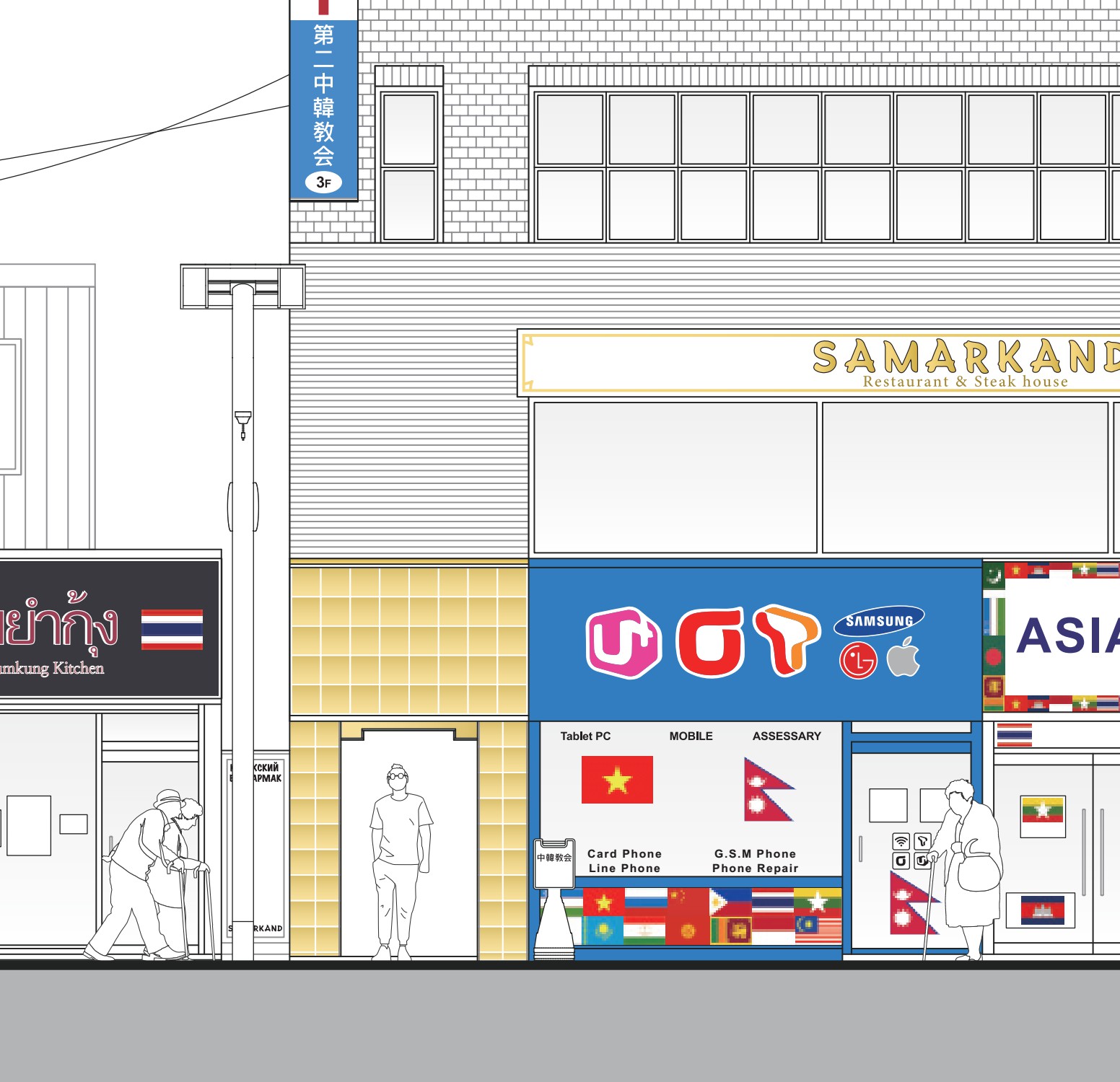

In the previous two instalments of the Mid-Size City Forum, ‘Global Mid-Size City: Cracks in Homogeneity’ and ‘Temporary Mid-Size City: A Tear in the Residential Fabric’ (covered in SPACE Nos. 687, 689), we examined the heterogeneous landscapes resulting from the influx of foreign residents as well as the profound changes to urban systems caused by seasonal fluctuations. This article identifies local universities and their international students as a meeting point between these two phenomena. International students residing in university dormitories serve simultaneously as temporary residents and a labour force within the region. At the same time, the university operates both as an educational institution and as a temporary labour camp for these students. This study reinterprets the university campus from the perspective of its unique urban and architectural structures in small and medium-sized (hereinafter mid-size) cities and proposes new modes of relational engagement.

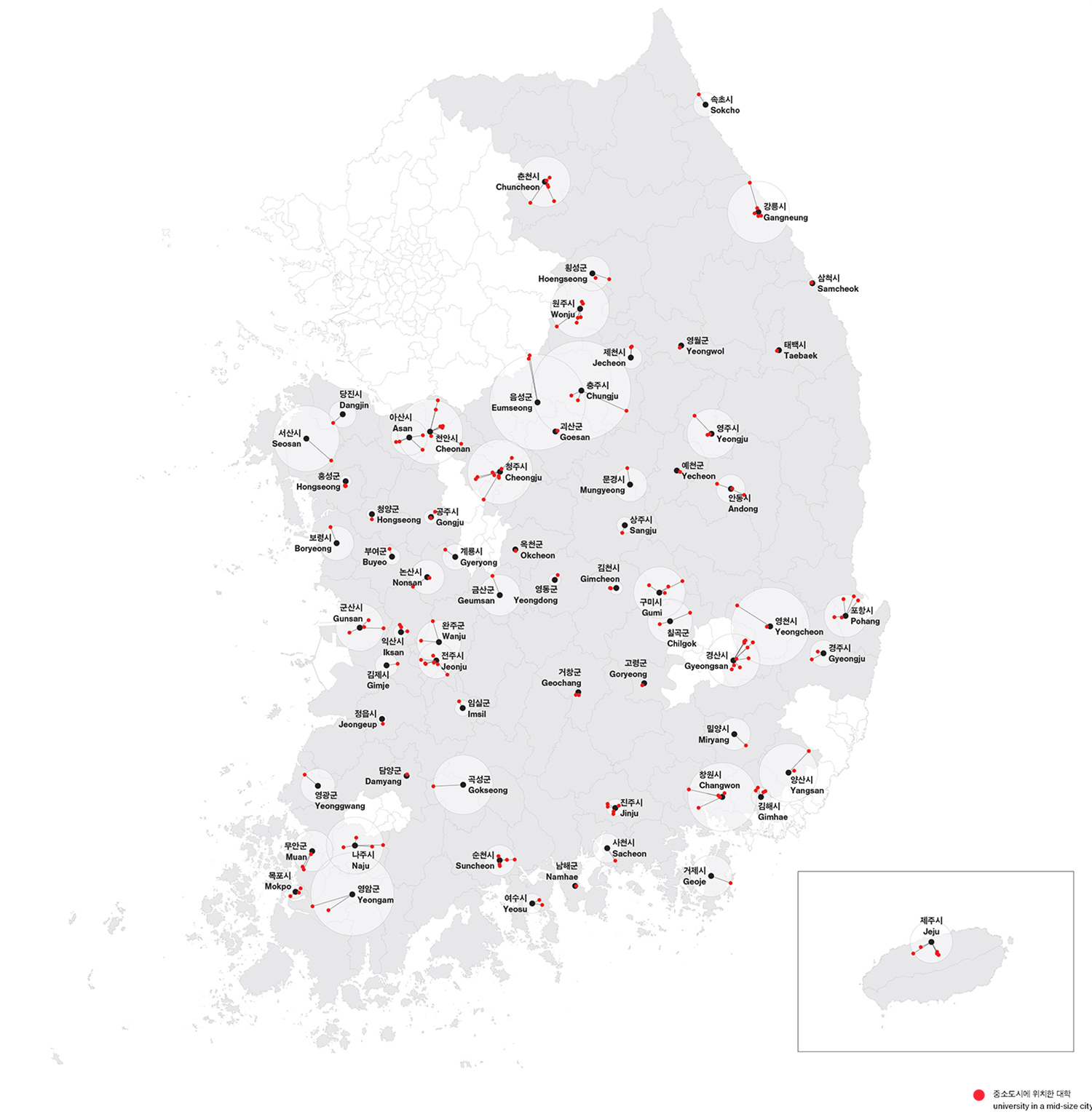

Distribution of universities outside the metropolitan area. A large number of new universities were established in these regions in the late 1990s and early 2000s following the expansion of the University Enrolment Deregulation Policy.

The mutational phenomena observed in mid-size cities pose a fundamental challenge to established notions of urban identity and permanence. They compel us to reconsider how we perceive and conceptualise the urban condition. What, then, becomes of a city in which such transformations are realised in their most extreme form? This issue focuses on the mutations of facilities occurring in Sokcho, Gangwon-do. As a city whose population fluctuates markedly with the tourist seasons, Sokcho provides a compelling case study of how traditional facilities are being redefined and used in mutational ways. By examining this shifting functionality, we may begin to discern the contours of a new typology for such facilities.

Tourist City Sokcho

Sokcho possesses both the natural environment and sensory experience required for a true resort destination. In contrast to Seoul – where the annual temperature range exceeds 28°C – the city enjoys a relatively temperate climate, with average seasonal temperatures of 22.4°C in summer and 1.5°C in winter. This comparatively moderate annual variation affords Sokcho a climate particularly suited to leisure. Moreover, with its proximity to Seoraksan Mountain, the East Sea, beaches, lagoons, and hot springs – all features seldom found within highly artificial urban environments – the city offers a setting that stands in stark relief to the increasingly systematized and anxious character of metropolitan life. In this sense, Sokcho presents itself as a refuge from the excesses of urbanisation. Historically, Sokcho was a city that relied heavily on fishing. In 1972, the number of fishermen in Sokcho stood at 32,224, approximately 43% of the city’s total population of 74,485. By contrast, in 2022, that figure had fallen dramatically to just 492, accounting for a mere 0.6% of the city’s inhabitants. The economic role of fishing, once dominant, has been all but eclipsed.▼1 In stark contrast to this, the tourism sector in Sokcho has seen steady growth since the late 1970s. In 1972, the annual number of visitors stood at 446,069, yet by 2024;▼2 this figure is projected to reach an astonishing 25 million.▼3 The transformation of Sokcho’s industrial structure, from fishing to tourism, can be traced back to the initiation of building development in Seoraksan National Park in 1976. The construction of Korea’s first condominium followed shortly thereafter, attracting a surge of urban tourists. These large-scale resort developments were closely intertwined with the rapid demographic expansion of the metropolitan area. As urbanisation accelerated and urban incomes rose, demand for leisure pursuits intensified. The introduction of a five-day working week further expanded available leisure time for urban residents. This, coupled with enhanced accessibility between Seoul and Sokcho, solidified Sokcho’s position as a pre-eminent resort city. The Seoul-Yangyang Expressway, completed in 2017, significantly reduced travel time between the two cities. Prior to its construction, travel to Sokcho from Seoul required transit via the Yeongdong Expressway and took approximately three hours and forty minutes. With the new route, that time was cut nearly in half to just one hour and fifty minutes. This sense of proximity between Seoul and Sokcho is set to intensify further with the anticipated completion of the Chuncheon-Sokcho Line in 2027. Operating at speeds of 260km/h, the KTX line will link Yongsan to Sokcho in a mere 99 minutes.

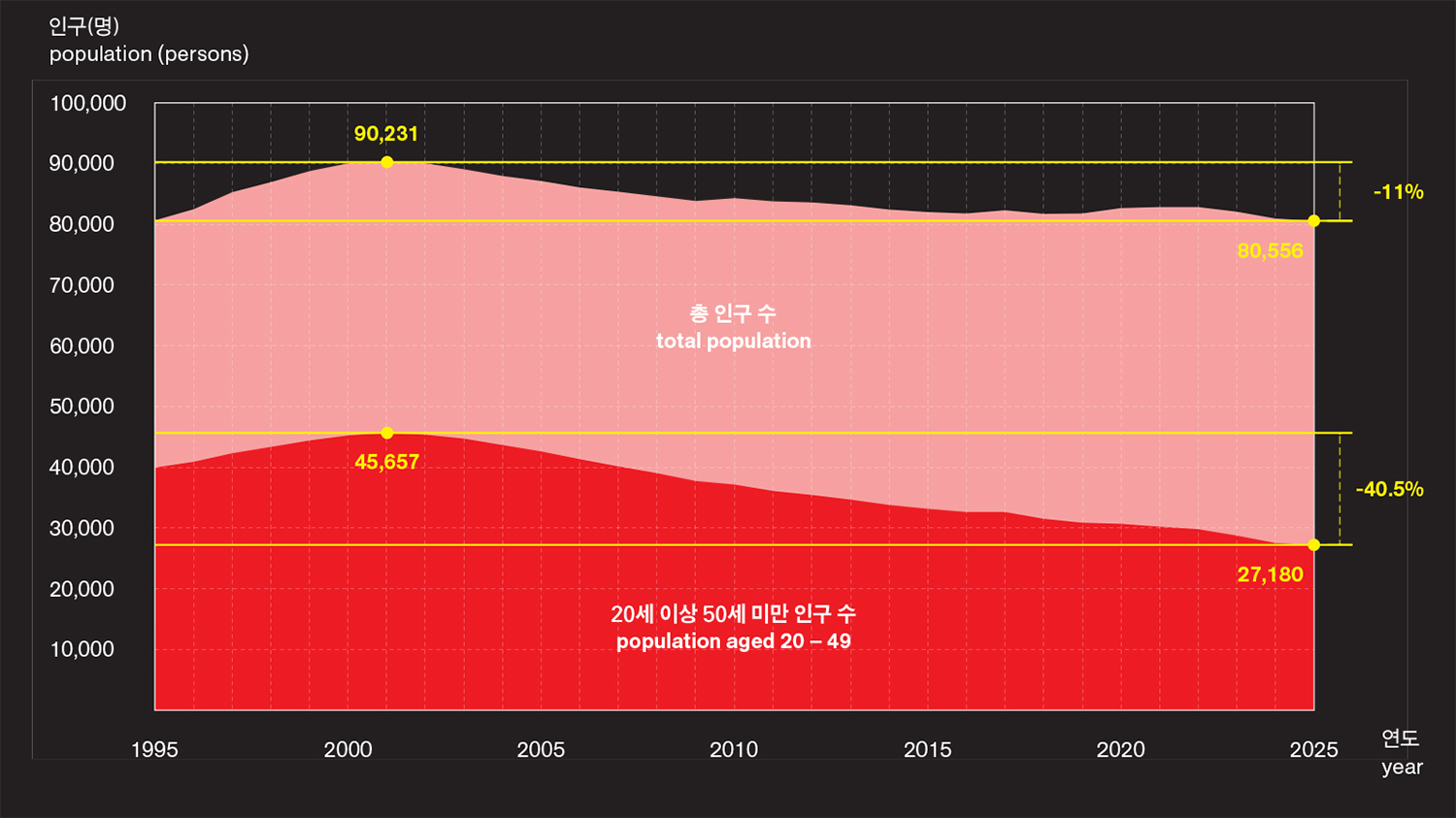

Trends in total and economically active population (ages 20 – 49) in Sokcho (1995 – 2025, data source: Resident Registration Statistics by Statistics Korea). While the total population decreased by 11%, the economically active population fell by approximately 40.5%.

The Supply-Demand Impasse

In the context of a nationwide decline in population,

a common strategy for preserving national competitiveness lies in the spatial concentration

of people and resources, thereby enhancing productivity and efficiency. Such a trajectory

inevitably accelerates the aggregation of the population in locations where

employment opportunities and industrial infrastructure have already been

established. Hence, even as the national population contracts, the demographic concentration

in the metropolitan area is likely to persist. However, the more vigorously productivity

and efficiency are pursued, the more intensely their antitheses are also desired.

Sensation in opposition to reason, transgression in contrast to routine, nature

against artifice, and slowness in defiance of speed—such desires emerge in

parallel, drawing increasing attention to environments capable of accommodating

them. Areas with excellent accessibility from the capital, in particular, are ideally

situated to serve as sites of leisure and respite for urban populations. Sokcho

is a city that meets these criteria with remarkable fidelity.

According to statistical data, the number of annual visitors to Sokcho reached 25,029,277 in 2022, 24,860,045 in 2023, and 24,779,951 in 2024. This is approximately 300 times the population of Sokcho. Although such a large number of tourists visit, they tend to be concentrated during specific periods. In the peak summer months of July and August, Sokcho receives 2,351,758 and 3,163,948 visitors, respectively. In contrast, during the off-season month of March, the figure falls to 1,676,560— approximately 53% of the August peak.▼4 This stark fluctuation between high and low seasons renders stable labour provision increasingly problematic. A large workforce is needed only for a brief window of time, while at other times the scale of this workforce is superfluous. As such, a stable and flexible source of labour capable of responding to these shifting demands is indispensable. Yet for smaller regional cities, particularly those experiencing declining birth rates and an ageing population, sourcing a young and renewable labour force is no straightforward task. The population of Sokcho, which peaked at 90,231 in 2001, has since undergone continuous decline, reaching 80,556 in 2025. More critically, when one isolates the economically active population aged between 20 and 49, the figures are even more revealing: from 45,657 in 2001, this cohort dwindled to 27,180 by 2025. That is to say, while the total population contracted by approximately 11% over this period, the economically active demographic shrank by a dramatic 40.5%.▼5 This precipitous decline in the labour force makes it ever more challenging to accommodate the rapidly growing demand from tourism. In response to this impasse, a new form of mutation is beginning to take shape in Sokcho.

The Crisis of the University

There are currently 422 universities across Korea, collectively enrolling 3,007,242 students. As recently as 1990, that figure stood at half its present scale. The surge in enrolment is directly attributable to the implementation and subsequent expansion of the University Enrolment Deregulation Policy beginning in 1996. Under this scheme, the number of students rose from 1,580,571 in 1990 to 3,130,251 in 2000 immediately following the introduction of the policy.▼6 In tandem with deregulation, the number of universities increased significantly, with 83 new institutions established. Admissions quotas were also expanded, rising from 388,000 in 1990 to 839,000 by 2005. Most of these newly founded institutions were situated outside the metropolitan area, as regulatory constraints rendered it difficult for Seoul-based universities to increase their intake.

However, a pronounced decline in the birth rate – beginning in earnest around 2002 – has precipitated a sustained reduction in the schoolage population. This demographic contraction has led to widespread under-enrolment across the nation’s universities. Over the past decade, first-year university enrolment rates have demonstrated a clear downward trajectory: 99.9% in 2000, 94.3% in 2010, 87.6% in 2020, and 86.2% projected for 2025. The pace of this decline is expected to accelerate, particularly given the renewed decline in birth rates that began in 2016. Annual births fell precipitously from 406,000 in 2016 to 230,000 in 2023, passing through intermediate lows of 358,000, 327,000, 303,000, 272,000, 261,000, and 249,000. This demographic downturn directly impacts university enrolment capacity, rendering it increasingly difficult for institutions – particularly those lacking competitive appeal – to fill their quotas. Since 2000, a total of 23 universities have been closed, and 34 others either merged or absorbed into other institutions. The overwhelming majority of these were located at considerable distances from the metropolitan area. Therefore, it is more and more evident that a university’s geographical proximity to the metropolitan area strongly correlates with its likelihood of institutional survival. In the face of these challenges, many universities are expected to pursue new strategies and breakthroughs in student recruitment.

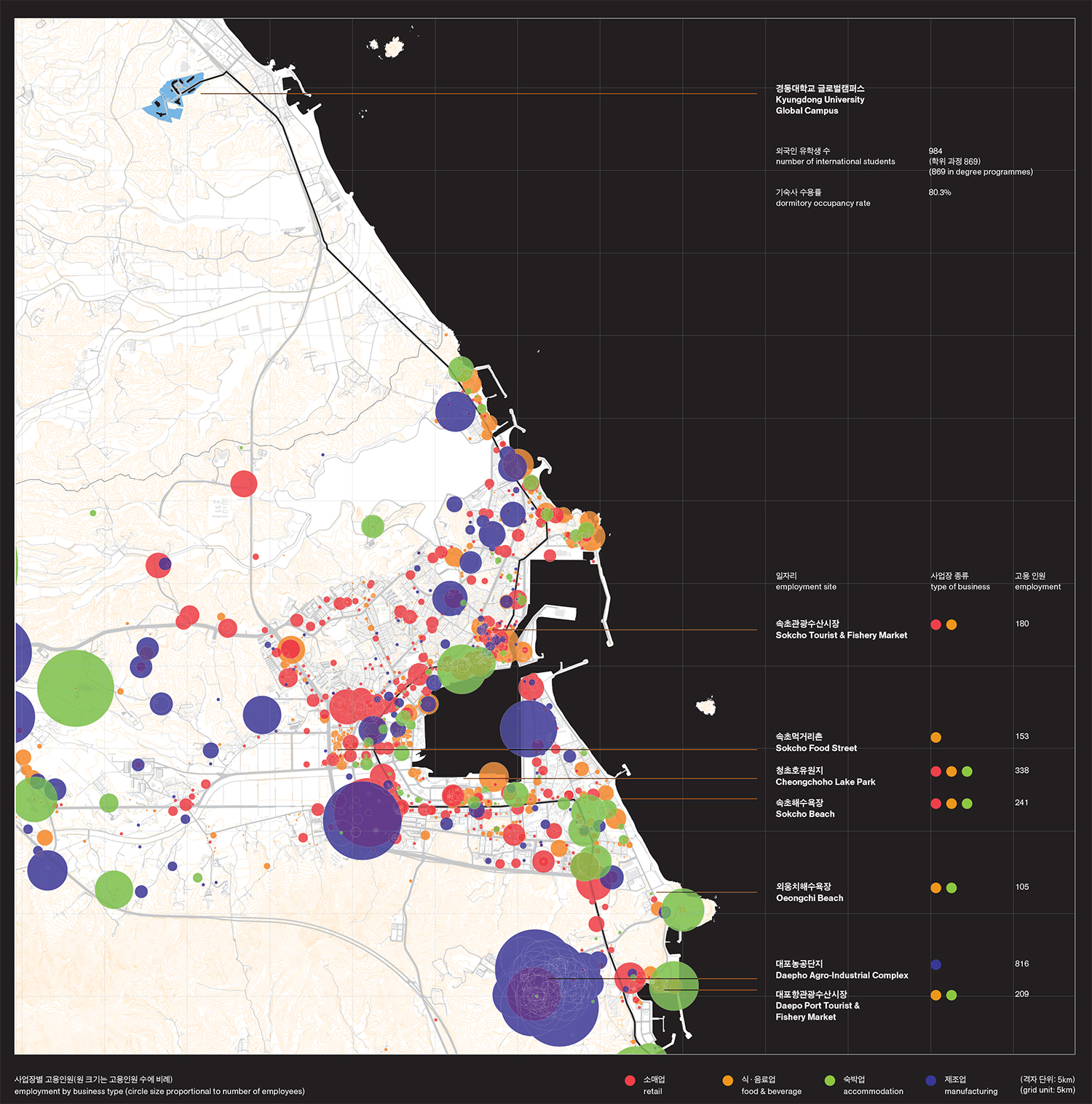

Map of Kyungdong University Global Campus and surrounding employment zones (employment data source: 2023 Employment and Industrial Accident Insurance Registration Status by Korea Workers’ Compensation & Welfare Service). Many international students at Kyungdong University earn income through part-time work in Sokcho’s city centre or nearby industrial estates.

International Students as Labourers

The economic impact of a single university on its local community is far from negligible. Universities contribute directly and indirectly to regional economies through student and staff expenditure and local procurement for institutional operations. A salient example can be found in the case of Seonam University, located in Namwon, Jeollabuk-do, which closed in 2018; it generated economic effects equivalent to approximately 4.5 – 6% of Namwon’s entire municipal budget.▼7 It demonstrates that the existence or closure of a single university can have a significant ripple effect on the local economy of a relatively small regional city. Recognising this impact, local governments and residents are working tirelessly to prevent school closures and attract new universities. (...)

_

1 Statistics Korea, 2025 Census of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

2 Sokcho City, The 11th Sokcho Statistical

Yearbook, 1973.

3 Korea Tourism Data Lab.

4 Korea Tourism Data Lab.

5 Statistics Korea, Resident Registration Population

Status.

6 Ministry of Education and Korea

Educational Development Institute, Statistical Yearbook of Education, 1990;

2000.

7 Moon Namcheol, ‘A Study on the Influence of Closure of University on Local Economy and Community: A Case Study of Seonam University’, The Geographical Journal of Korea 55.3 (2021), pp. 261 – 274.