SPACE October 2023 (No. 671)

ʻI am an Architectʼ was planned to meet young architects who seek their own architecture in a variety of materials and methods. What do they like, explore, and worry about? SPACE is going to discover individual characteristics of them rather than group them into a single category. The relay interview continues when the architect who participated in the conversation calls another architect in the next turn.

interview Lee Younjeong, Jeon Piljoon co-principals, Studio李心田心 × Youn Yaelim

Art and Architecture

Youn Yaelim (Youn): Studio李心田心 (hereinafter LeesimJeonsim) is comprised of two principals who majored in fine art and architecture respectively.

Jeon Piljoon (Jeon): Principal Lee majored in printmaking, and I am an architect. We work on product design, furniture design, interior design, and architectural projects together. For product and furniture design, we have a separate brand named 李心田心Design (LeesimJeonsim Design), which is led by Lee. We have different specialties in separate areas, but at the ideas stage, we talk a lot without distinguishing between architecture and products.

Lee Younjeong (Lee): Whether it’s at home or in the studio, we have developed a natural exchange of opinions. Then, once the idea is consolidated and in production, we develop it through our respective areas of expertise.

Youn: I heard you started working together when you were studying abroad.

Jeon: Lee majored in fine art, but she was interested in architecture and the city. If you look at our graduation work, her work is as if from architecture, and mine is like painting! (laugh) We were able to develop our ideas by overlapping our fields, and organically, LeesimJeonsim was created.

Youn: The expression ‘creating objects that urban spaces need’ noted in principal Lee’s profile impressed me. Why did you begin to focus on cities and architecture while majoring in fine art?

Lee: When I moved to Seoul for my undergraduate studies, I saw a cityscape that was different from where I had lived before. It was like a mass-produced product on a shelf. I traveled to many other countries and felt that ‘cities’ were part of a monolithic culture, with only the language as the differentiating factor, and that the same architecture was repeated. It seemed like all cityscapes were structured in the same way. I wanted to paint the landscape around me informed by the similar visual structures found between cities and commodities. At the time, I was working in two dimensions, dealing with architecture and cities, but now Iʼm focusing on making three-dimensional pieces and furniture.

Youn: Principal Jeon, on the other hand, was interested in paintings. (laugh) Where did your interests intersect?

Jeon: The common language in both of LeesimJeonsim’s architecture and product design is simple, geometric form. One of my favourite photographers is Michael Wesely. Wesely takes long-exposure photographs with very small apertures, over months and years. So, the old things are clearly visible in the photo, the new things are blurred, and above all, the simple trajectory of the sun is clearly visible. We often think of nature as very complex, but if you observe it over a long time, you realise that what you end up with is very simple, geometric shapes. We are looking for the same original shapes created in nature.

Youn: Is that why the buildings of LeesimJeonsim follow geometric principles?

Jeon: We try to view all the elements of our surroundings, including architecture and people, as single entities. We think about the nature and presence of a building not only in terms of the architecture, but everything that surrounds it as an consistent or egalitarian entity. This allows a much more expansive way of thinking than approaching a structure in context. For instance, the skylight of Triple Square House (covered in SPACE No. 627) is not a means of taking in the landscape and daylight in the way typical of architecture, but acts as a visual device that uses the projectivity of light to create geometric shapes, giving the space a rhythm as the light through the skylight shifts and creates tracks in the centre of the space 365 days a year. We tend to think about how each element can have a pure presence that occupies and dominates a space.

Entities, Not Contexts

Youn: I feel that whether it’s architecture or product design, the scale or the medium through which the idea is realised is simply different. It doesn’t seem to have a big impact.

Jeon: Sometimes I hear architects around me say, ‘Your design appears indifferent to the surrounding context,’ but I think there should be a lot more buildings that individual as opposed to highly sensitive to context. Context is not a goal, it’s a result of the process.

Youn: It’s refreshing, since architects often make a virtue of how a building responds to its context.

Jeon: I think it might be a kind of debt awareness, because Korea has a short architectural history, and a lot of heritage has been destroyed and lost over this time. In Europe, there is so much meaningful architectural heritage, but their history is long, and the buildings that have been selected and chosen for preservation over hundreds of years have remained and become the places that people visit in the present. So, I felt that the meaning and role of architecture is clear, and the reasons to respect its contexts are also clear. However, in Korea, I wonder if context can be a criterion that can be valued as the absolute norm and category of value judgement.

Youn: What got you into that mindset?

Jeon: A lot of my architectural thinking was shaped by my time at Foster + Partners. I was really impressed with the way they define the shape of architecture. It records the geometry and shape of the building, the DNA of the shape, so to speak. It creates a trajectory that is detailed enough that anyone can build on that data and create the same shape of building. Itʼs interesting to be able to first establish the order in which buildings are put together.

Youn: In your diagrams as well, one is able to discern the DNA of the shape.

Jeon: My interest in ‘shapes that can be defined’ continues to this day, as I donʼt begin designs with the functions of a building or the arrangement of a programme, but rather by asking questions of how to combine simple architectural elements into shapes that can be diagrammed and designed. I do the same when teaching students.

Youn: It would be interesting to learn architectural design from you. (laugh)

Jeon: Students find it interesting and challenging at the same time. Last year, I assigned a site for the Gyeongsanggamyeong Park in Daegu, which is a place where a lot of elderly people gather. Instead of analysing the site, I asked them to scavenge for interesting objects. Some students found old cassette tapes at a junk shop, some brought in a record player, and from there, they started designing.

Youn: How can new design be sparked by a record player?

Jeon: Normally, you would start by analysing the context of the site and the adjacent buildings. However, I try to get them to explore visual structures on a broader scale. I think there’s a periodic homogeneity in the shapes of objects and architecture. For example, thereʼs an odd resemblance between the archetypes found in products like old disks, cassette tapes, and record players, and the design of the architecture of the time. The archetypes change with time, place, and circumstance, but I think there is something that’s always consistent, and that’s what I want them to find.

Youn: What have you discovered as the visual structures defining our present era?

Jeon: I have been paying attention to the way minimalist artists look at objects: they create pure forms that are not connected to any object, so that the individual nature of the work becomes evident. Recently, repetitive, geometric shapes are also present in the work of various architects, and I think this is a common grammar that is related to experimentation across neighbouring artistic fields.

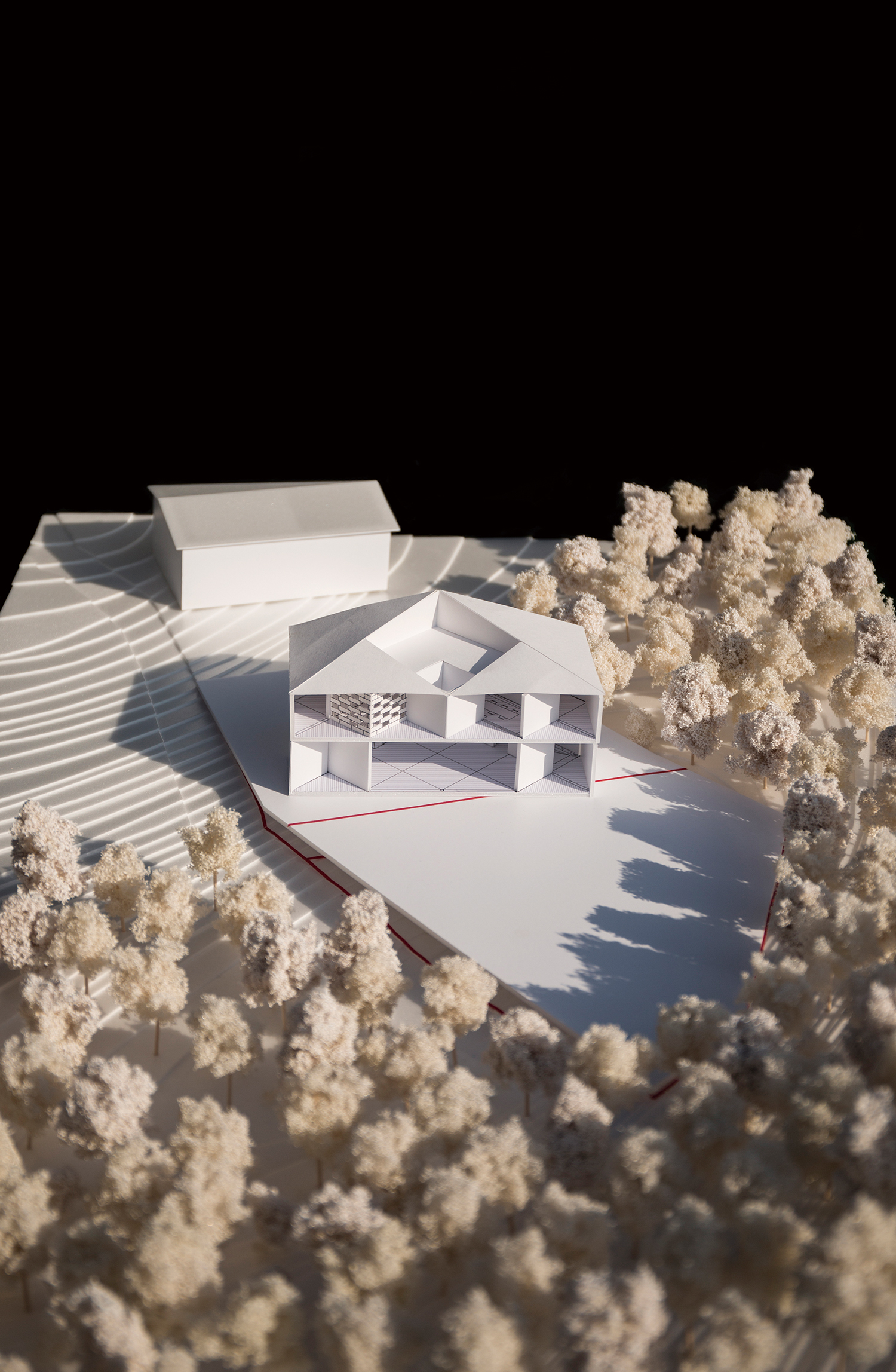

The model of Two in One House ©Studio李心田心

Not the Same Way

Youn: The more I hear from you, the more I am reminded of two of your graduation works, architecture-like painting and painting-like architecture. (laugh) Now I understand why the two of you continue to work together.

Jeon: Different architects seem to have different perspectives on cities and architecture, but I often feel that they are homogeneous in some ways. When we design programmes, functions, and the size of specific spaces according to the needs of clients, it is easy to end up with a ʻbuilding like a buildingʼ. However, when we find the emphasis on the presence of each entity rather than the elements that are emphasised in architecture, we can work in a different way through the eyes of artistic fields. I am trying to create a ʻbuilding that does not look like a buildingʼ through communication with Lee.

Lee: In fact, despite the meaning of name ʻ李心田心ʼ, which is a homophonous idiom meaning ʻthe communion of heart with heart,ʼ we often disagree with each other. (laugh) But I think itʼs the disagreements that make us think outside the box. This is probably the reason why we maintain our identity as a duo that has its own separate scope but shares ideas. Apart from the outcome, the aspect we value the most is the the process of sharing ideas and developing them together.

Youn: Do you plan to continue operating the way you are now?

Lee: I have been making specific things, a soban (tray table), for a while, and now I’m interested in working with objects again. My goal is to find a way to implement my ideas architecturally, while still being independent of the architectural work of Jeon.

Jeon: There are definitely challenges in terms of how the studio should operate. We are practically working as an independent design duo, and I’m wondering if that’s going to continue, because right now we are partnering with different architectural firms for the practical aspects of the post-design phase. My concern is that in the future, when our projects are more in demand, it will get to a point where it is difficult to handle it on our level, and we will have to figure out how to produce them. We will keep our working process and design philosophy, but we will have to continue to explore what we want to do beyond our work.

Youn: Perhaps, in the future, it might no longer be the two of you alone.

Lee Younjeong, Jeon Piljoon, our interviewees, want to be shared some stories from Kim Myoungjae, Choi Yeojin(co-principals, Plot Architects) in December 2023 issue.