SPACE September 2023 (No. 670)

ʻI am an Architectʼ was planned to meet young architects who seek their own architecture in a variety of materials and methods. What do they like, explore, and worry about? SPACE is going to discover individual characteristics of them rather than group them into a single category. The relay interview continues when the architect who participated in the conversation calls another architect in the next turn.

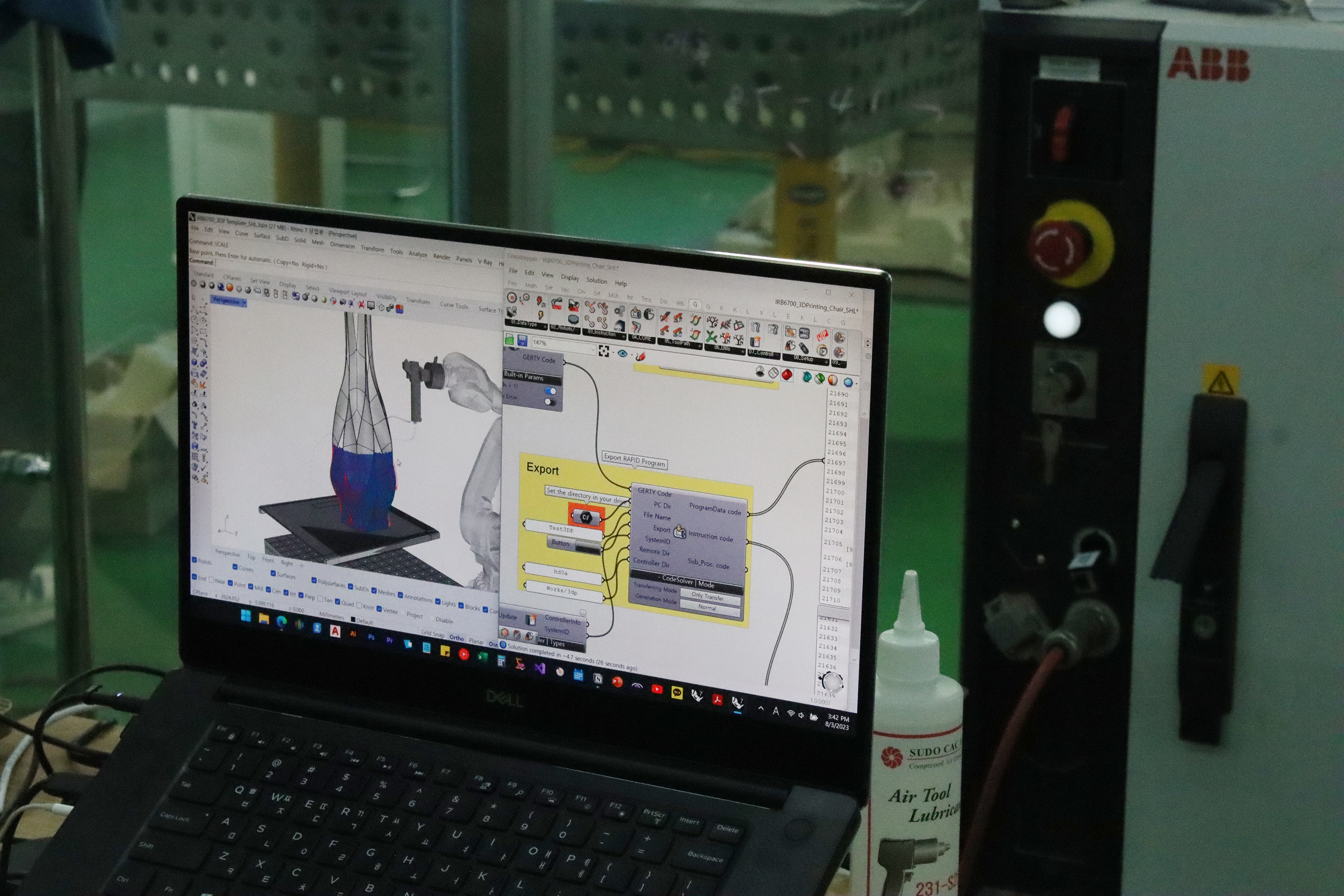

WAAM experimental model

interview Park Hyungwoo principal, B.A.T × Youn Yaelim

In Search of Helpful Hands

Youn Yaelim (Youn): Is this place your office? There is a hint of a factory-like atmosphere.

Park Hyungwoo (Park): This must be your first time visiting such an office. (laugh) There is also a research lab in Seoul; however I invited you here to introduce you to our real working space.

Youn: The person working hard on the robot inside is director Ko Minjae, right?

Park: Yes, it is. There is not much time left on the delivery due date. Since he is concentrating on his work, I will be in charge of the interview.

Youn: I heard director Shin Donghan is currently in Canada for a while. Everyone seems busy. How do the three of you divide your roles?

Park: It is mainly my job to figure out which method to use in the production process and how to handle details. Director Shin develops the appropriate software per the method, and director Ko then applies the software to operate the robot.

Youn: The current three members are also the co-founders of B.A.T. Please tell us how you embarked on this together.

Park: Shin and I known each other for a long time, from our undergraduate years to graduate school. I believe we were both skilled at making things with our own hands. We always regretted the limitations of technology in expressing what we imagined, even though tools in architecture were increasing in numbers and advancing. At this point we agreed to try to differentiate ourselves from other architectural design firms.

Youn: So you found the solution in robots?

Park: ʻDesign and buildʼ. Looking around for a machine or a facility that could make this possible, we found that robots were a perfect fit. As we were not professionals in robotics nor programmers, there was need for a tremendous amount of research. We started to research the means of and techniques behind using robots in

architecture. We met Ko at a workshop in the process. He was an outstanding participant.

Youn: There are other imaginable possibilities when conceiving new means of production. Why did it have to be a robotic arm?

Park: Construction is largely done by human hands. That is why we wanted something close to a human hand. A robotic arm can be controlled like a human arm as it is mobilised on 6-axis and replaces various processing devices at the ends. Normally machines are programmed to perform one task. However, robotic arms can perform different actions such as additive manufacturing, subtractive manufacturing, and stacking.

Youn: What do you mean by 6-axis?

Park: Hold out your arm and try rotating it. The shoulder joint rotating is the first axis, the elbow joint is the second axis, the third axis being your wrist, with the joints on your fingers following as fourth, fifth, and sixth axes. A robotic arm similarly has six axes, yet is much more capable of practicing delicate work.

Youn: Can it exceed 6-axis?

Park: You can use more attachments to add axes. This can be achieved by a positioner that spins around like a pottery wheel. It can result in a freer form, however currently there are limits to such attachments. This is an area that needs further development.

Everyone Has the Right to Create

Youn: Now I believe that it is now time to share what technology B.A.T is developing.

Park: We develop and provide a software named GERTY, which controls industrial robots. Simply put, tools such as pencils and hammers held by robots are called end devices. We design these end devices and produce software which control them.

Youn: How does this technology controlling industrial robots connect to the architectural field?

Park: Industrial robots have been actively used in manufacturing production lines for a very long time. However, it was mainly used for some repetitive processes. Those robots are moved by a programming called ʻteachingʼ. When a person teaches the robot the route and movement to move, it moves as it is taught. On the other hand, GERTY controls the robot based on shapes. If you freely design a shape with a 3D design programme, it extract the shape based on the modeling data. It is a CAD CAM system that integrates CAD (Computer Aided Design) for design and CAM (Computer Aided Manufacturing) for manufacturing. It is a technology that easily realises a shape based on input data, and because it significantly cuts the amount of man power and costs in production. I believe that this will be much needed in the non-standardised architectural design field.

Youn: When thinking back to the days of my studies, a friend who could freely use modeling tools had no qualms adopting or devising atypical designs. Along the same lines, GERTY may open up a whole new world of creative possibilities for designers who use the technology.

Park: I believe that it enables broader lines of thinking and expression. Currently we provide software packages that are subdivided by appliance, such as lamination and cutting. However, there is an entry barrier as it requires a proficiency in tools such as Rhino and Grasshopper.

Youn: Is more time needed to become more widely used by regular users?

Park: In order to be used universally, the software market and our technology still needs to develop. One day, I hope that the day will come when anyone can use it, whether they be architects or artists. B.A.Tʼs operating philosophy is often referred to as the ʻdemocratisation of designʼ. We want everyone to be able to create their own designs and drawings.

Mediating Imagination

Youn: B.A.T. demonstrates a different use compared to previous uses by combining familiar materials such as plastic, metal, tiles, etc. with robotic arms. How did you achieve this originality from familiar ingredients?

Park: I am always thinking when I see architecture. If I see an atypical building I ask myself, ʻif we were to construct this building how would we build it our way?ʼ We start with existing materials but explore different ways to employ and reimagine them, expanding their range of use.

Youn: Design and production are organic processes. How does the working methodology of B.A.T allow a freer flow between the two?

Park: The questions concerning how to manufacture something starts with a design. Designs can of course emerge after thinking about a manufacturing method first, but it is more interesting to contemplate production methods when someone comes up with a sketch and asks, ʻIs this possible?ʼ B.A.Tʼs current goal is to be the intermediary

between designers and manufacturers. We are the bridge that connects them after bouncing around the unknown barrier between design and production.

Youn: Do you ever feel the urge to design yourself, instead of existing as the mediators?

Park: I had an urge when we first opened. But we decided that we could not take on the designing roles as designers and have a somewhat authoritative or decisive tendency. Dictators cannot be mediators! I believe it is meaningful that our technology made it possible to realise a complex design conceived by the architect. Dreams, Universe, and Architecture

Youn: I read a recent article about the construction of the largest building in Europe using a 3D printer in Germany.

Park: It is basically the same technology, yet it is a different destination from where we are heading. The printing equipment will be directly on site and actively stacking up the building. However, we are not yet confident in directly controlling the robot on site. It is important that it is operated under certain conditions. Maybe itʼs because our technology is still developing. In fact, the reason why I sought such a large workspace was because I imagined a robot building a building in it. The images of robots building a large building, moving via the rails laid on floors. However, the more we research and develop our technology, the more our initial thoughts have changed as we face the realities.

Youn: What were the limitations you faced in reality?

Park: Applying our technology will require various experiments in diverse ways, but the problem is that the architectural and construction industry is rather conservative. There needs to be an R&D process in which one can experiment, confirm, research and develop, while continuously exchanging information with the construction companies. However, on construction sites no one is willing to allow for an R&D period. They just want to see the results. Without research, there is no choice but to get involved in superficial things that do not require a structural solution. It would be best if we could grow our technology together, but it is not easy.

Youn: It is an environment in which is not easy to accept new attempts. There may also be cost issues.

Park: The first areas to show interest are on the manufacturing side. As we designed a programme that was best suited to customisation of each different architectural design, and this coincided with the needs of the manufacturing industry. In particular, Wire-Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) is widely used in the automobile industry.

Youn: In that respect, it seems like the possibilities for use in various industries are endless. What field interests you most in these days?

Park: At present, we are focusing on WAAM and Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF). We have conducted several experiments using an eco-friendly PLA plastic in the form of pellets. It seems that there are possibilities for using plastic in the architectural field as concrete forms. However, this is one of the areas that needs further R&D. Once we overcome present difficulties, we would like to expand from the automobile industry to ship building and the space industries. Recently, in the U.S., a space craft using a similar technology was launched, with investment from NASA.

Youn: You are already up there just through technology alone.

Park: Through technology, yes! (laugh) We want nothing more than to be actively involved in architecture. We are waiting for the conservative nature of the architecture market to shift. Currently it has a high threshold, and so we are waiting for the right time while still trying to keep our toes in the market. One day, we would like to construct buildings by using robots alone. This may not be easy in the next life either. (laugh)

Park Hyungwoo our interviewee, wants to be shared some stories from Lee Younjeong, Jeon Piljoon (co-principals, Studio李心田心) in October 2023 issue.