SPACE November 2023 (No. 672)

[DIALOGUE] Architectural Intuition in Ken Sungjin Min’s Ananti Projects

John Hong professor, Seoul National University × Ken Sungjin Min principal, SKM Architects

In many situations, a prelinguistic utterance precedes formal language: it can be an intuitive, ‘instinctual’ response before a structured sentence is formed. Because babies communicate with utterances such as babbles and cries, the assumption is that these prelinguistic vocalisations are merely ‘primitive’ speech acts. However, linguistic philosophers Deirdre Wilson and Dan Sperber, who continue to theorise the utterance, state that ‘we have many more concepts than words. […] in most relatively homogeneous speech communities in human history, less than a dozen new words […] would stabilise in a year. On the other hand, the addition of new concepts to an individual’s mind is comparatively unconstrained.’▼1

If we suspend the idea that utterances are inherently less developed versions of structured thinking, they can be seen as an emergent form of communication—a kind of proto-language. And in this way, they can be seen as inferring multiple and layered meanings that resist reduction into clearly defined terms. In terms of architectural language, utterances can be forms and spaces that are beyond the explanatory capacity of diagrams.

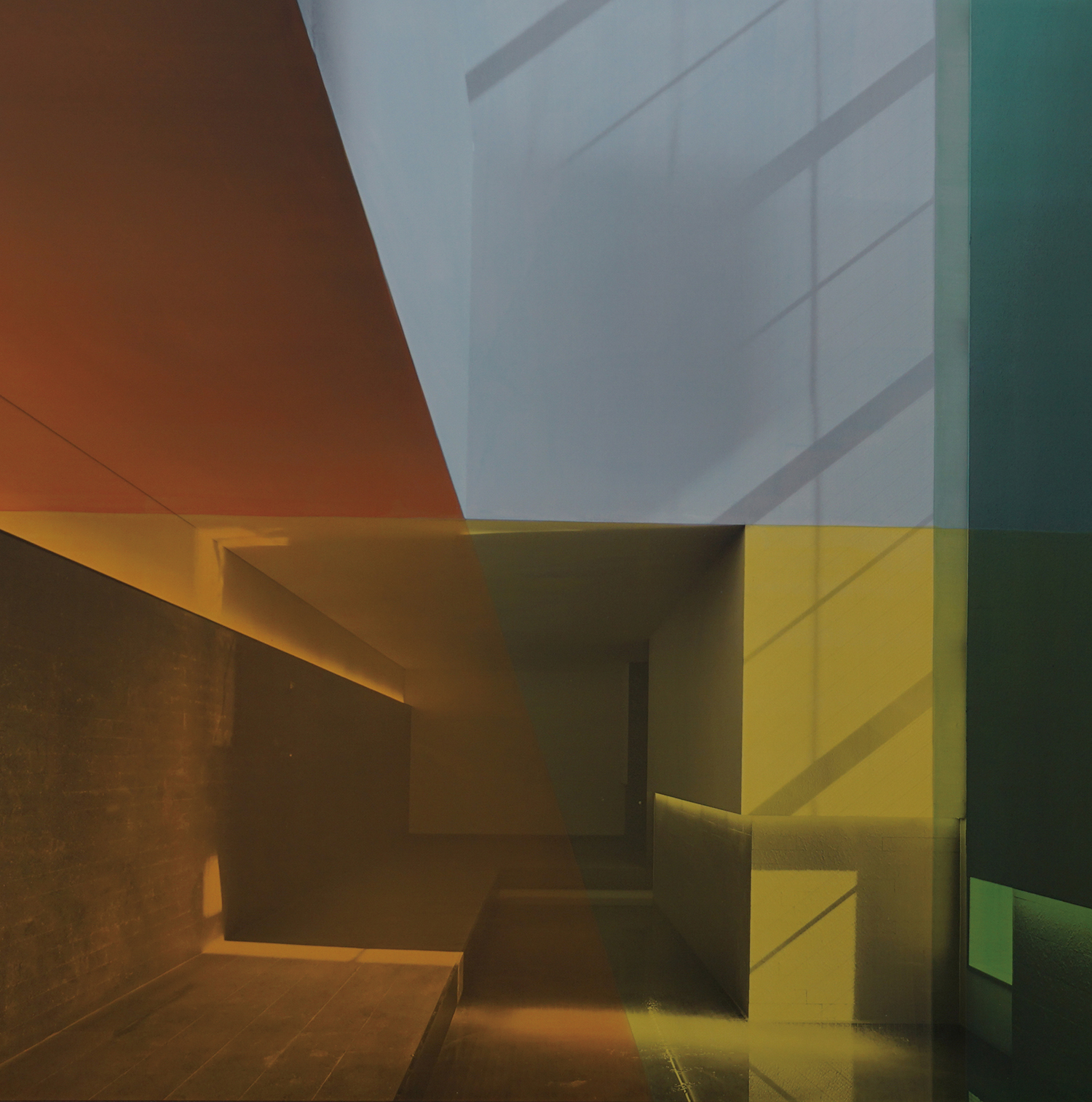

For example, the recent Village de Ananti and Ananti at Gangnam projects are embedded with the quality of utterances in their formal arrangements, experiential qualities, and the processes through which they were designed. When speaking with the architect Ken Sungjin Min about these architectural themes, there is never one simple answer to a question: his responses are derived from a mix of logical reasoning, personal memories, and speculative possibility. Moreover, rather than a vertical hierarchy of architectural elements where smaller details are contained within the logic of the larger project, his deployment of the language of form and spaces seems to place elements into horizontal relation: the scale of a railing becomes just as important as the scale of the entire urban arrangement.

This is not to say that the SKM Architects’ resulting design is a ‘random’ assortment of ideas. The intuitive architectural and urban forms in the recent Ananti projects are born from a deep reservoir of experience. For instance, when we visit a historical section of the city that has transformed over time, it is difficult to point out one cause and effect that shaped it. Diversity has evolved from multiple forces—some of which might on the surface be contradictory. Even though it is challenging to interpret the many ideas within the utterances embodied in the Ananti projects (the very nature of pre-linguistic communication is that organised sentences do not easily come to mind), it is an important step to unpack the layers of design decisions so that they can inform and develop new avenues of discourse.

Dialogue

John Hong (Hong): Where there are a large number of dwelling units as in the Ananti projects, there is always the challenge of how to aggregate them in a meaningful way. Without some concept of how to arrange units, we’ll end up with repetitive apartment blocks. Therefore, architects will typically inject some kind of system into the repetition to create variation: a set of rules that might include rotating, shifting, scaling, etc. In the case of the Village de Ananti, however, there are multiple, subtle permutations in place: there seems to be an ‘utterance’ here that guided you—an unexplained intuition that preceded formal rules. Can you explain your overall planning strategies?

Ken Sungjin Min (Min): Village de Ananti can be said to be a ‘village’ consisting of a large central plaza-like lawn and the sea in front. Five towers composed of various units including six duplex units occupy the front of the site facing the sea, low-rise mansions, and an arrangement of detached villas are located at back of the site. This is similar to a city composed of a variety of elements that then forms a community cluster. Just as people are drawn to the diversity that one can experience in cities like New York or Paris, the overall plan of Village de Ananti was designed with this diversity in mind. In that sense, I thought this was a very urban space—even as we’re surrounded by nature. I come here often, but it always offers new experiences with various activities and spaces, and at the same time, it gives me the comfort of a village. In the end, if you can give someone the feeling of ‘I want to come and live here,’ wouldn’t that be the best compliment?

One of the most important aspects of the site plan is that people can have a different experience with each stay—they can visit multiple times while changing their accommodation each time. In particular, the strategy for the Manor House complex, which consists of single-family homes, was to give the impression and feel of a village that has existed for a long time. Taking advantage of the terrain, the homes are quietly hidden among the surrounding trees rather than standing out as individual objects. To avoid the sight of repetitive, identical houses lined up in a row, ten courtyards offer different experiences of the journey to each accommodation block. With old villages in Korea, when you enter from the main road, you come across a large courtyard with trees. People will gain a sense of orientation from within this area. This sequence of discovery was important to our design—the entire complex was arranged by changing the angle and orientation of the roof geometries. To create a village atmosphere, the roof height is set at around three to four metres and takes on a variety of appearances: not too high or too low compared to the surrounding trees.

Hong: You mention the importance of heightening human experience in design, but how do you know what people seek? For instance, the design for both Ananti at Gangman and Village de Ananti stems from your own personal experience, but these experiences resonate with many visitors: the materials and architectural forms seem to communicate at some visceral level.

Min: We value designing for people’s experiences over being good at drawing diagrams. I start with my own experiences and memories of what I thought were good spaces as a stepping stone. I tend to remember aspects of scale as it relates to comfort—these collect in my mind in what we might call human-scale space: irregular yet regular patterns, angles that conform to the terrain rather than arbitrarily set to geometries. Could it be that these characteristics come from experience? Looking back, I think I designed the entire complex while thinking about establishing strong figural principles, enhancing the sense of nature, and human experience—all at once from the beginning of the design.

Architecture is not about creating an external appearance, but organising the actions of people contained within it. It was a valuable experience to be able to check people’s actions and reactions to our design during the duration of multiple projects. We were able to reflect our experiences incrementally from one project to the next. Meanwhile, people’s tastes change all the time. Even if you conduct a survey to understand customer needs, once it is reflected in a finished built work, choices must become more diverse. Having many choices is linked to ‘freedom’. This is in line with the values we ultimately pursue in the Ananti projects.

I am the third of five siblings. When I was young, my mother, worried that the five children were growing up wild and insensitive, made us take care of dogs and plants. We raised a fairly large dog outside, and one day I insisted that she stay inside. If I brought a dog inside the house with paws dirty from being raised outside and fur that would shed, it would be difficult to clean up after her. Logically, my mother could have objected—but in this case, my mother gave me ‘freedom’ and accepted my request. Thanks to this, I was able to sleep together with our dog on a mattress on the floor for a few days. This is just one of the many instances where my mother let us try something outside of the boundaries—to let us test the limits and, importantly, the responsibilities and consequences of freedom. At Ananti projects, I also want to give people options to let them creatively experience a sense of freedom. Architects’ intuitive decisions are similar. They challenge themselves to do things they don’t necessarily want to do in order to achieve better creative results. The problem-solving experience that follows these decisions nourishes them—just as my mother anticipated and allowed for the problems that her son’s choice to sleep with a dog would bring. Elements of this intuitive decision-making are present in the Ananti project, from the master plan to the details. Someone might find a genetic connection between the curves of the towers, the curved surfaces of the restrooms, and the curved finishes on the ceilings of the guest rooms. (laugh)

Hong: When talking about an intuitive ‘utterance’ in terms of the design process, there is never a direct line that leads to the final design solution. The design process is inherently ‘inefficient’ because it needs to be exploratory. However, in the final product, there is a tight efficiency to your work: one example is the curve incorporated into your tower masses (hotel & condominium)—in elevation it is very gestural, but in plan, one can see a highly efficient use of space. How do you converge the intuitive utterance and the rational final design?

Min: Since I directed the entire process from initial planning to master plan and interior design, it was an opportunity to coordinate parts within a whole. You may think that I have a strong sense of form-making based on the curved surface of the back of the tower, but this external form is the result of consideration from the initial planning of the tower, rather than adding a shell after the internal programs were determined. In order to express a village-like sequence that naturally follows the terrain, we created pedestrian movement that rises slowly up the site through stairs and escalators. Since the towers rise from the middle of the site, it was important to reflect this same sense of movement and flow in their design, even though they are vertical structures. However, the expressive curve at their back cannot be created unless the stair core is laid out efficiently in plan from the beginning. Yes, from a functional perspective, it would be possible to place the guest rooms in the front, place the core parts such as the elevator, staircase, and equipment room in an ‘L’ shape in the back, and then finish this part in a box shape. However, the curved shape is the result of considering both the plan and elevation simultaneously, rather than considering either one first. Rather than moving in a logical and orderly manner according to a perfectly fitting system, a model was created and continuously modified to organise it into its current state. The curved surfaces in the towers were poured in layers of custom-made, elaborate metal gang forms, saving money.

During the six years of creating Village de Ananti, I wanted to explore materials, colours, and planes rather than simply following the design vocabulary of Ananti Cove in Busan, which I had worked on for the previous five years. Isn’t intuition the difference between humans and artificial intelligence? Architects and designers are people who suggest lifestyles for the near future and even 100 years from now through their own experience and intuition. This is why I experimented with and challenged colours, materials, and the planes where they were applied, both on the interior and exterior of the rooms. An additional challenge in terms of the finish materials was the use of cement tiles within the hotel rooms, rather than something ‘domestic’ like carpet. Contrary to concerns that this might be too out of the ordinary, I heard many people praise it in terms of both aesthetics and maintenance.

Conclusion

One of the most important aspects uncovered in this discussion is that intuition and spontaneity in the design process do not lack conceptual depth. In architecture, particularly, the opposite is true, because there are necessarily multiple complex factors to simultaneously consider such as materiality, codes, behaviours, natural forces, to name a few. In the case of the Ananti projects, an intuitive response projects through, then synthesises layers of entangled characteristics.

This is exemplified in Ken Sungjin Min’s discussion on ‘elements and components’. Where ‘elements’ are the basic architectural fragments that we are all familiar with such as windows, ceilings, and cladding, ‘components’ are their imaginative combination. The way a roofline is shaped, the way water and hardscape come together, and the way different types of residences form a community, are all based on multiple layers of micro and macro decisions based on previous experience, current technologies, and future projections of societal needs. This is why the architectural utterance – the very way a wall is curved or the way angles in a site plan are derived – defies a simplified description: their multiple significances differ per context and by who is experiencing it.

In this way, Ken Sungjin Min uses the term ‘genetics’ to describe the result of layered ideas and experiences. The intuitive process demonstrated in the recent Ananti projects is a culmination of three decades of design research conducted in his office, historical precedents that he continues to study and rediscover, and personal interactions with the many cities he has visited over the years. These ‘genes’ appear as similar but transformed components that are shared in both the Village de Ananti and Ananti at Gangnam. Rather than just surface similarities of materiality or geometry, they share deeper relational principles with the overall sequence of experience.

An utterance is not a struggle to communicate per se, but rather the difficulty in reducing multiple ideas into a formal sentence that abides by current rules of grammar and vocabulary. As Wilson and Sperber theorise, ‘What is explicitly communicated by an utterance typically goes well beyond what is said or literally meant […]’▼2 Similarly, could we look at an architectural utterance as a more advanced proto-language that cannot yet be explained by current norms? In this way, the multiple layered ideas represented in the recent Ananti projects are nascent. They come into existence by their relationship to connotations and contexts; therefore, it is the receiver rather than the creator that ultimately performs an imaginative interpretation in assigning meaning. This is an important aspect of the new Ananti projects: rather than binding the design to what can be diagrammed and readily explained, Ken Sungjin Min leaves the final action of inferring the meaning of his architectural form-language to us.

1. Deirdre Wilson and Dan Sperber, Meaning and Relevance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 44 – 45.

2. Ibid., p. 14.

Architecture. His work bridges the scales of architecture and urbanism and merges the mediums of drawing, materials research, theory, and computation. He was associate professor in practice at the Harvard University GSD and has held visiting professorships at other major universities including the University of Pennsylvania.