ⓒChoon Choi

Noryangjin Sewage Walk: Thoughts on Emptiness

The drainage crossings, or culverts, discovered under the railroad tracks in Noryangjin between 2008 and 2011 are now open to the public. Traversing over a hundred years of history, it is now an underground passage permitting pedestrian access to the fish market. The oldest segment has a horseshoe-shaped section with an elegant brick vault supported on solid granite walls and crosses under the railroad tracks for the Seoul-Incheon Line, which opened in 1899. Including this 20m vaulted segment, the passage includes five different sections, each designed in a distinct structural shape and technique, spanning 92m. A square-shaped concrete box extends the brick vault by 11m under the portion of the railroad that doubled the number of tracks for the Seoul-Incheon Line in 1969, coinciding with the beginning of Korea’s rapid industrialisation and local cement production. The next segment, built under the tracks added between 1995 and 2006, has a gothic vault section and may predate the square-shaped segment. It is assumed to have been introduced for the electric streetcar network, which extended its service area beyond Noryangjin in 1952. Several underground sewage tunnels from the early 20th century still survive and are protected by the Seoul Metropolitan Government as historical sites. However, the Noryangjin Sewage Walk is the only place open to the public. It is not merely open but fully accessible as an integral part of the local pedestrian network. Neither a museum nor a monument, it is an authentic heritage site that now carries pedestrians instead of rainwater.

ⓒChoon Choi

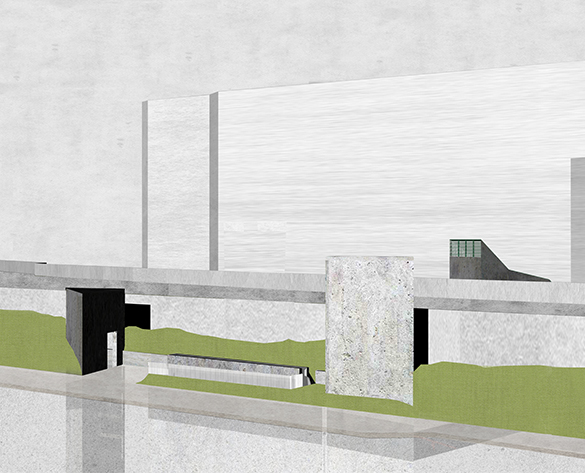

The entry pavilion for the Noryangjin Sewage Walk is conceived as an extension or protrusion of the underground civil infrastructure rather than an architectural object. The goal was to create an assemblage of misfits foreign to the adjacent streetscape. The triangular towers were initially conceived to be tall enough to be seen from the passing trains but have been lowered for cost control. One tower houses an elevator and ventilation shafts, and the other is an exhibition room. A crack appears between the two towers for a stairway, and midway down the stairway, the landing is extended to become an exhibition space with a circular skylight that resembles the maintenance hole, which used to be the only means of access for the drainage crossings. An intense ray of light enters to fill the space with a mysterious glow. The lower half of the stairway is shaped like a half vault with a crevice at the top for faint natural light that dims as you continue your descent. Once your shadow merges with the darkness, a long tunnel appears with a series of vaults that glow without an apparent light source. No outlet is visible, and there is no artificial obstruction. Only a violent rumbling sound of the trains chugging along overhead periodically interrupts this emptiness.

ⓒChoon Choi

Emptiness is often the feeling that accompanies the completion of a design project. This emptiness can be attributed to a sense of shame from untold failures and shortcomings. But what if emptiness is the intended goal of a project? Can a sense of accomplishment coexist with a sense of emptiness? Can one say, ‘I haven’t done anything’, not out of modesty but with a sense of pride? The project’s official title for the Noryangjin Sewage Walk was the ‘access facility for underground pedestrian passage’. It is technically a road, not a building. The Flood Control Division of Dongjak-gu Office managed the project. Civil engineers oversaw the construction. There was no scope of work for architects. My involvement was officially advisory and practically voluntary. In other words, my job was to do nothing and leave no trace. If emptiness is the pre-existing condition for a heritage site, its preservation efforts should aim to protect the residual values of an empty space. The passage of time eventually dilutes architectural concepts and gestures, but the heritage sites retain what is essential within them as testaments of collective will and social consensus. The process of preservation is a filtering process for disparate voices, both human and non-human. All voices should have equal weight, and the architect must assume a posture of passivity with a muted voice until the dissonant noise is transformed into music. For silence and emptiness to remain within public spaces, architects sometimes need to hide or disappear. The faint traces of more humble architectural thoughts may be harder to erase from the memory than monuments and landmarks. Architecture may be understood as a state of being if an architectural thought can seep through the crevices within pre-existing emptiness to become part of its permanent past.

The Noryangjin Sewage Walk is unique among other heritage sites because it is part of the underground infrastructure, never intended for human occupancy or public viewing. Not an architectural object built as an implicit symbol of power and capital, it is a mythical place outside collective historical memory. It is not a public statement but a personal soliloquy. To make a place that will be immediately hidden upon completion, bricks were carefully laid to enclose a void, and now a ghastly ray of light enters through a crack that has appeared within emptiness. (written by Choon Choi, edited by Bang Yukyung)