SPACE January 2023 (No. 662)

Magok Cultural Center: Remembrance of Spaces Past

Architectural heritage sites as artifacts frozen are seldom more than inorganic apparitions or the virtual image of a place that has ceased to exist. They are representations of the past imagined by the living observer of the present moment. A feeble intervention within the faint illusion intensifies as the inorganic phantasm is transformed into an object of desire. On the other hand, spaces embedded within freshly excavated artifacts and newly discovered heritage sites transcend the burden of historicity, moving into the realm of the sublime. When we realise that the vastness of our universe will remain forever beyond the human capacity for recognition and recollection, we accept the possibility that natural history exists independently from human presence and that human history is a mere representation of an objectified past, soiled by the narrator’s nostalgia.

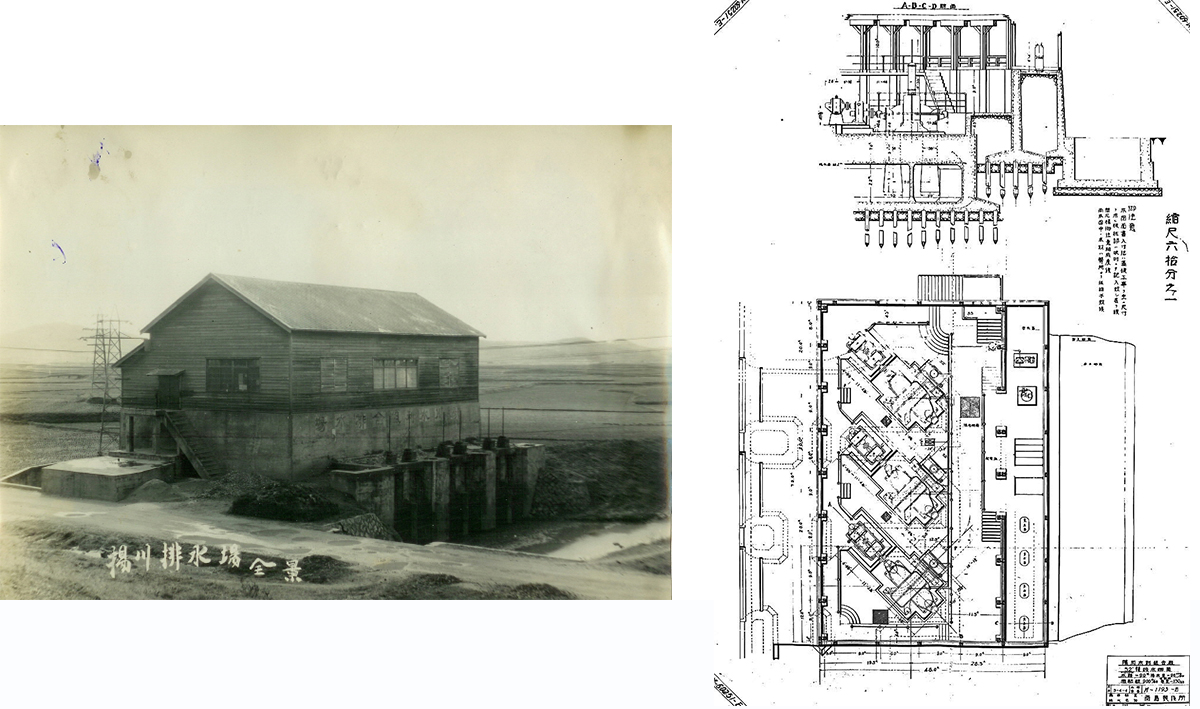

(left) Drainage Pumping Station of former Yangcheon Irrigation Association, pictured after 1928 / (right) Improvement construction drawing of Yangcheon Irrigation Association, 1928 (collection of National Archives of Korea)

The Magok Cultural Center was built in 1928 as a pumping station by the Yangcheon Irrigation Association, founded in 1923 to manage the surrounding rice paddies of Gimpo. Designated as a registered cultural heritage site No. 363 in 2007, it is the only agriculture-related facility among all the historically registered industrial sites. The timber frame structure with king-post trusses was preserved and refurbished, while the interior spaces were left empty in their found condition. The design team hoped to maintain its meditative emptiness for private contemplation instead of recreating a false version of the disappeared past. If the preservation of the timber structure above ground respected its historical value, the rehabilitation of the underground spaces was an effort to protect its authenticity as a pumping station. The underground space had remained buried and hidden since the 1990s when the building was leased as a factory. The exhumation of the underground space was also a willful act of converting a spectre of the hidden past into a physical reality. No one had any memory of the space that had been buried for over 30 years, and there was no proof that anything remained. The design team had to rely solely on a few original drawings. When we finally entered the space for the first time shortly after the excavation, the space, strangely familiar yet foreign, instantly transported us back to the time encapsulated within the drawings. The sublime interior of the excavated space leaves a pure, unfiltered, and indelible impression, reminding us that inorganic matter is also subject to the passage of time. The disembodied space of non-subjective abstract memory is brought to life in the present.

ⓒChoi Seungho

ⓒChoi Seungho

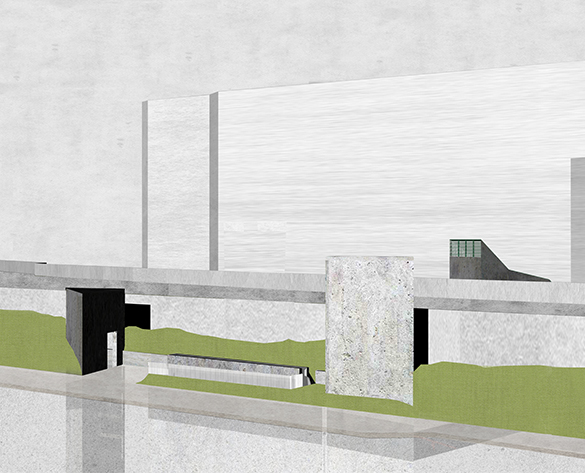

The design team divided the work into three vertical layers. The restoration layer on the top had to follow a specific set of rules and regulations specified by the heritage protection guidelines, which mandated that the timber structure and other original elements above ground be faithfully preserved and restored. Distinctly different materials were used for newly added elements, such as access ramps and stairs, all of which were separated physically from the original surfaces and independently supported. The middle layer is the concrete plinth above ground, designated as an exhibition zone. The large opening made for the factory became the main entry door, and a series of retaining walls were added around the plinth to set it apart from the surrounding landscape. Taking advantage of the new structures, multiple entry points were added on various levels through the courtyard, terraces, ramps, and stairs. Graffiti was left in its place to avoid privileging an arbitrary time in the past. Lastly, the underground space was preserved as an excavation layer where the memories of the inorganic matter replaced human memory to present an unfamiliar scene of nonhuman historicity. In addition to the symbolic value of exhuming the buried past and rehabilitating it into the present time, it served as a more authentic exhibition content.

ⓒChoi Seungho

ⓒChoi Seungho

The circulation pattern overall follows the paths of water in and out of the building. It offers a rare opportunity to witness human beings, non-human beings and matter coming together to form a composite historical narrative. The willow tree, with its roots penetrating the cracks in the concrete, succinctly demonstrates the mystic pull of the space within, blurring the boundary between the organic and inorganic worlds. The history embedded within industrial heritage sites cannot be limited to human experience but also includes the world without humans or the material world in itself, suggesting a possibility that human and non-human beings and things may have equal agency in historical recollection and ecological reconciliation. (written by Choon Choi, edited by Bang Yukyung)

ⓒChoi Seungho

ⓒBang yukyung