I Am Going to Be More Mobile with My Motor▼1

1.

There was a time when I commuted from Mapo-gu to Gangnam in Seoul, while working as an intern at a large company at Seonneung Station. I took Line 2 at Hapjeong and I thought every time I took the subway: commuting hours should also be included in working hours. I was serious, even though of course it would not work for the employer. If you want someone to work at a fixed time from nine to six, then a company should also be responsible for the time and effort people make to keep that time. Of course, no one listened to me. It was similar to when I was commuting from Mapo-gu, Seoul, to Paju Publishing Complex in Gyeonggi-do. At first, I took a wide-area bus, and later I used my own car, but I couldn’t rid the feeling that something was wrong: what is this waste of time? Why does everyone drive out at the same time and suffer the traffic jams? The person who created this system must be crazy. My mother, on the other hand, told me that my way of thinking was stranger. My mother believed that every man should drive his car to get to and from work in the morning and evening, marking a transition to adult life.

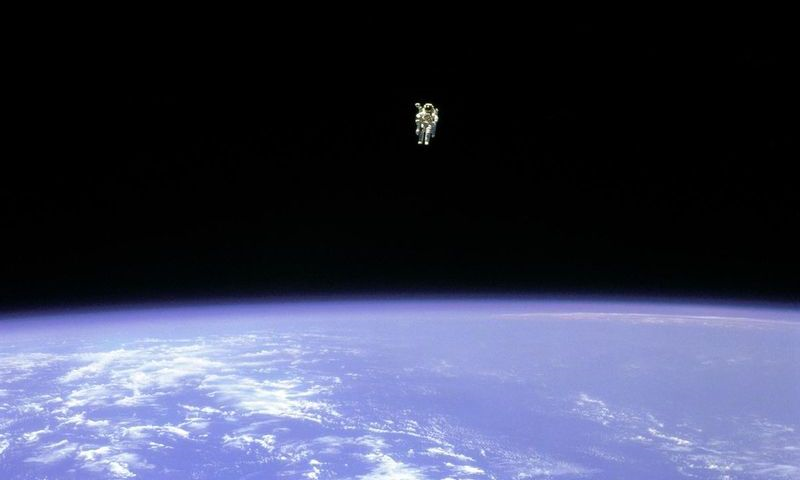

Berna Yazıcı, who studied the problems posed by rush hour from an ethnographic approach, analysed traffic as a ‘social condition in which urban inequality occurs’. Istanbul spans Asia and Europe with the Bosporus Strait between; there are two bridges used by a million commuters, or 10% of Istanbul’s population, every morning. Labourers are transported in truck compartments, office workers are on packed onto buses, and wealthy people drive their own cars. What was interesting was people at the extremes of class. The elite travel by helicopter or by ambulance-taxi across the city to avoid the traffic jams. An ambulance taxi is a personal ambulance owned by those in the highest class. The poor, on the other hand, just walk. Despite the city's harsh environment, such as security issues and intense weather, there are no alternatives but to walk. One is exempt from urban transport, and the other is excluded.▼2 In summary, mobility is identity, power, and ideology.

2.

Most of my travel routes these days are limited to Mapo-gu, Seoul. I travel from Mapo-gu Office to Hapjeong, Mangwon or Yeonhui-dong and use a shared bicycle or kickboard. It is faster and simpler than using buses or cars, but it is inevitable that one is threatened by cars or looked at curiously by people. I felt guilty after the enactment of a law concerning kickboards and sensational articles in the media suggesting kickboards are a urban tyrant and a weapon deployed on the streets, as seen in articles published almost every day such as ‘Electric Kickboard Accidents on the increase 8 fold in 3 years’▼3 and ‘A famous comedian almost got into an accident by “recklessly driving a kickboard” during a shoot’.▼4 But if you think about it a little deeper, this is weird. Really? Is the kickboard that dangerous? What about the car?

Geographer Tim Cresswell says movement consists of three parts: physical movement, the reenactment of movement, and the embodied and experienced nature of movement.

In the reenactment of movement, movement is always divided into good and bad by the state, institution, or media. Developing countries reproduce railroads and automobiles as suitable transportation methods, while developed countries encourage walking as a good transportation method. Following this aspect of reproduction, the kickboard becomes an evil that threatens the existing order. Who gave them the power to occupy roads and sidewalks! Kick the kickboard out! But the real problem isn’t a small kickboard running at 20km/h; it’s a car. It is also cars that cause accidents, encroach upon the sidewalks, pollute the environment, and defile the appearance of the street. Who gave that authority to the car?

Cars rule the urban landscape in Korea. The power of automobiles is so severe that we don’t even realise they have such significant power. This phenomenon is known as naturalisation; a particular ideology has become the established order, like heterosexuality or the patriarchy.

Debates related to the Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Crimes, also known as the Minsik’s Act after a child victim of a car accident in a child protection zone, are also to be considered in line with the perceived authority of the car. The act is a law that strengthens the safety of child protection zones. At the same time as the law was enforced, an article was posted on the Blue House national petition to abolish the Minsik’s Act (a petition for the revision of the Minsik’s Act on March 23, 2020). The main point of the petition, which has the support of 350,000 people, is that aggravated punishment is against equity and that the driver is considered a potential criminal. Anonymous drivers claim it is a fool’s errand with the phrase ‘Minsik’s Act play’ at a core of their argument, claiming that there is a trend among elementary school students to jump in front of cars to put drivers in trouble. According to their assertion, elementary school children are worse than a protest group that threatens self-injury. This attitude was further promoted with the article ‘Spreading Fears of ‘Minsik’s Act Play’: Earn Some Pocket Money by Touching Cars in Front of Schools’.▼5 But, of course, there is no case in which this play has been proven to exist. Why are the Act and children so reviled? The way drivers think of themselves as victims is strangely similar to that of men connected to sexual crimes: not all men should be considered potential sex offenders. The fear of imaginary threats and hatred of minorities and the weak, which has intensified due to the COVID-19 and the economic crisis, are no exception to locomotive power.

3.

It is fortunate in that sense that cars are being recreated in a way that is increasingly negative in terms of circulation. The media and the government also encourage walking and cycling and reproduce impressions of them in a positive light. But in fact, the point is not which mode of movement is good or bad as demonising cars to an extreme extent is also a one-sided view. Cars can also be a means of increasing women's power and shaking the gender hierarchy. The film ‘Thelma & Louise’ offers the most famous example of this; Neil Archer claims the film has shown the potential to explore complex questions about identity, desire and pleasure.▼6 The same goes for racial issues. Until the 1960s, black drivers were blamed, but the black bourgeoisie, who acquired a new economic position, enjoyed freedom on the interstate highway designed by President Eisenhower during the Cold War. Even in the conflict between indigenous Australians and white settlers, the automobile takes on the aspect of complex representation. Mobility was a major factor in the establishment of the colony. White people created an image of aboriginal groups as car-fearing savages, but the native people created their own automobile culture. In a sign of resistance, the aborigine Murumyu Wallabara declared that they would drive to the capital Canberra with a tribal license plate as a sign of resistance. It re-contextualised the power of automobiles.▼7

Mobility is a dynamic through which institutions, industries, gender, race, and class intersect. In this network, movement is bound to be reenacted while at the same time surpassing it. Virginia Woolf praised the car’s movement as much as the walk; her interest was in the mix of diverse connected to the fluidity of the androgynous spirit connected to the fluidity of the androgynous spirit’.▼8 Therefore, if you want an egalitarian society in which diversity is respected, the means of transportation must also be equal. Movement by changing devices, and not travel by one means: Perhaps the intersection of different kinds of movement makes our identity more flexible. Using multiple means of transport means meeting a more diverse range of people and encountering urban landscapes with greater intimacy.

1 Peter Adey, Mobility, trans. Choi Ilman, Seoul: LPbooks, 2019.

2 Rivke Jaffe and Anouk de Koning, Introducing Urban Anthropology, trans. Park Jihwan and Jeong Heonmok, Seoul: Ilchokak, 2020.

3 The Financial News 3 July 2021.

4 The E-Daily 3 July 2021.

5 The Korean Economic Daily 6 July 2020.

6 Neil Archer, 'Genre on the road: the road movie as automobilities research', Mobility and the Humanities, ed. Peter Merriman and Lynne Pearce, trans. Kim Taehee, etc., Seoul: LP, 2019.

7 Georgine Clarsen, ‘“Australia – Drive It Like You Stole It”: automobility as a medium of communication in settler colonial Australia’, iMobility and the Humanities, ed. Peter Merriman and Lynne Pearce, trans. Kim Taehee, etc., Seoul: LP, 2019.

8 Peter Adey, ‘Mobility’, trans. Choi Ilman, Seoul: LP, 2019.