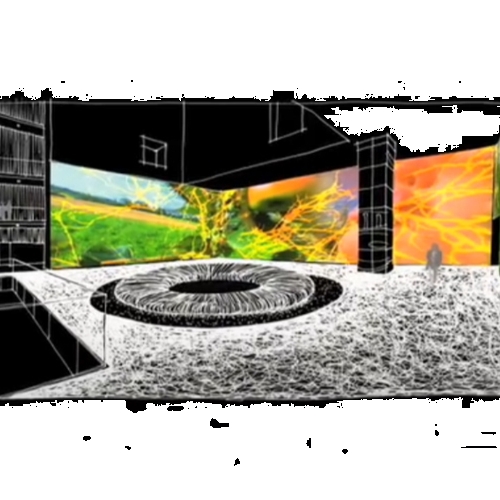

(upper image) screenshot from YouTube channel of MoMA

Museums Are Where You Can Find Yourself▼1

I was long an admirer of the White Cube. Considering that this as a gallery space has become something of a cultural cliché, I must be a layperson in contemporary art discourse. However, there are practical reasons why I, a cinephile who loves black boxes, came to love the museum's white cube.

A Private History of the White Cube

I had never been to an art museum until I entered a university in Seoul because I was raised in a local family with a high Engel coefficient. I was around 23 years old when I first visited a commercial gallery in Samcheong-dong with a friend. It was a shock. They pose such clean, pleasant, comfortable, and pretty spaces, but you don't have to pay an admission fee? The toilet in the museum was cleaner than that in my own flat, to the extent I could lie on the floor. The urinal had a fly sticker aimed at the nudge effect, and the hand wash smelt like musk. To be honest, I think that was when I experienced luxury hand wash for the first time. At that time, I thought, ‘I’m going to live here’. Sitting on a designer-made bench, I never got bored, even after many hours. A friend said, ‘Let's go home, please’, and I said, ‘But this is my home...’

There are numerous reasons why I liked the White Cube so much. It maintained a pleasant temperature regardless of the season, fellow visitors of a refined and friendly impression, there was no timetable like in a cinema and there is no-one eating nachos beside you. Moreover, it doesn't appear to matter whether you look at the work or not. Two hours can be interminable if you choose the wrong movie or play. If you don't like the exhibition, you can just pass. Regardless of the work, you can walk through the space, look at your cell phone, meditate, date, and take pictures. Of course, there are people who think you are pathetic. However, I don’t care! There is no place as comfortable as an art museum for a student without money. It is a space of escape from the loud noise of the world and the mess of your home, an autonomous and utopian white temple.

The features of the white cube listed above mirror those advocated by modernists such as Adolf Loos and Le Corbusier; a neutral and unpolluted sacred white space. Behind the aesthetics of the White Cube lies the legacy of Western imperialism and concealed colonialism, which is now the subject of criticism. See the truth that perfect white has hidden and expelled! Art museums began to pursue change, such as complicating their discourse or introducing black boxes.

A Private History of the Black Box

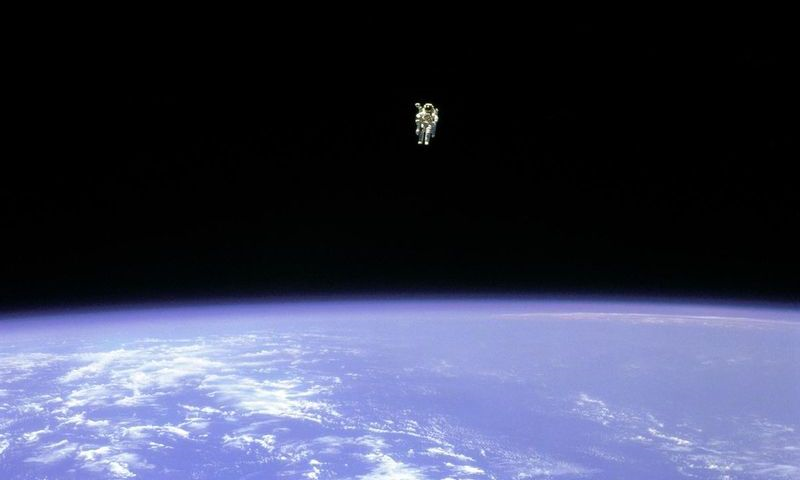

There is nothing distinct about a black box. In the eyes of media theorists like Lev Manovich, the black box in a movie theatre is a ‘large cell.’ In the genealogy of the screen, the cinema can be located at the apex in the history of visuality that originates with Plato’s cave. The black box that requires the immobility of the body and a fixed gaze causes the confinement of the subject. Therefore, it creates a passive and acritical crowd or consumer.

Of course, this is only a theoretical assumption. Even after I became an admirer of the White Cube, I often went to the black box, the movie theatre. The way I use the theatre is as follows: buy tickets for late-night time on weekdays; don't buy popcorn, but I do buy a coke; sit in the ergonomically designed multiplex's fluffy seats, sip a sip of cola, and I expel a sigh of satisfaction in this tranquillity. When the movie starts, it's not long before I fall asleep... and after waking up, I go to the bathroom. At this point, the running time remains for about an hour. In the middle, I looks at my cell phone and wait for the movie to end. When the movie is over, I slowly walks through the empty streets and returns home. They also look for reviews about the film on the portal. It's better if you don't see (one star). ‘Tsk. So, why did you go and see that?’, I murmur. The friend who listened to my movie watch said the same thing. ‘Tsk. So, why did you go and see that?’ I answer, ‘To drink a coke’. ‘You can drink a coke at home’. ‘Well… I wanted to walk a little’. ‘You can just walk?’ ‘Well… I wanted to take a nap?’ ‘That also can be done at home! Hold on a second, why are you going to the theatre?’

The Third Place

There is something strange about the discourse comparing the white cube and the black box. Artists and critics elaborate on the origins of the two spaces and analyse the concepts behind artists using these spaces. Still, there is not enough mention of the people who use them. Or, it is said that the autonomy of the white cube has become a tool for selfies by the unthinking viewers embracing a neoliberal market logic, or the visibility of the black box has become a tool for the unquestioning gaze of thoughtless audiences. Whenever I hear such theories, I think, 1) Is the audience so negligent? 2) This concerns space, so why is there no consideration of space? To elaborate on 2), the discourse about the white cube and the black box seems to account for the characteristics of the space, but in reality, it is about the way the work is reproduced and the way the work is experienced within these spaces (or the about the artist who produced the work). In other words, in both cases, they are obsessed with visuality (as a metaphor). However, people may not be going to see the work. You may have thought that you should watch go to an exhibition or watch a movie, but in reality, you may be going there because the context or ritual surrounding the space is comfortable and formed by habit. Serious reviewers may contend that you came to a museum (or theatre) and didn’t really engage with the work. But is the work that important? Really? For me, the white cube was a living room on the street, and the black box is a bedroom on the street. When the work is pushed back, another possibility for space opens up.

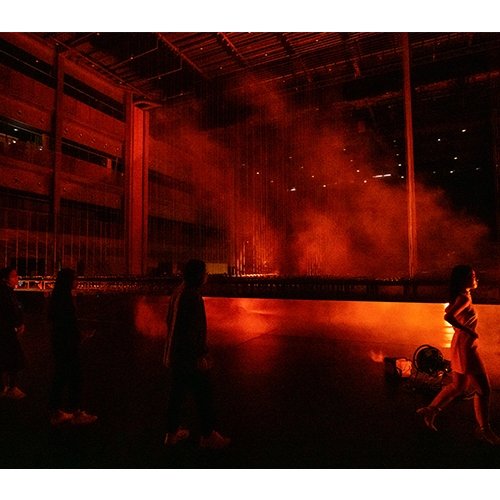

Ray Oldenberg, an American urban sociologist, emphasises the importance of informal public life. People need spaces other than those found at home and in work. The place where such informal public life takes place is called the ‘third place’. Are the white cube and the black box these third places? Of course, there is a big difference between the two spaces and the features that Oldenberg suggests. Oldenberg said that conversation was essential to the third place, but these are almost absent from the white cube and black box. Nevertheless, the two spaces were the exits that allowed me to enjoy an ‘informal public life’. The process of entering, exiting and passing by without any direct interaction with people and the ritual behaviours of receiving brochures and buying a coke is a kind of social exchange. The Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist said in an interview on the huge video installation, Pour Your Body Out (2008): ‘In life, you are often alone, but when you gather in an imagined room in a “museum”, you become a common body’.▼2

1. ed. François Bovier and Adeena May, Exhibiting the Moving Image: History Revisited, trans. Kim Eungyong, Seoul: Mediabus, 2019, p. 93.

2. Ibid, p. 111.