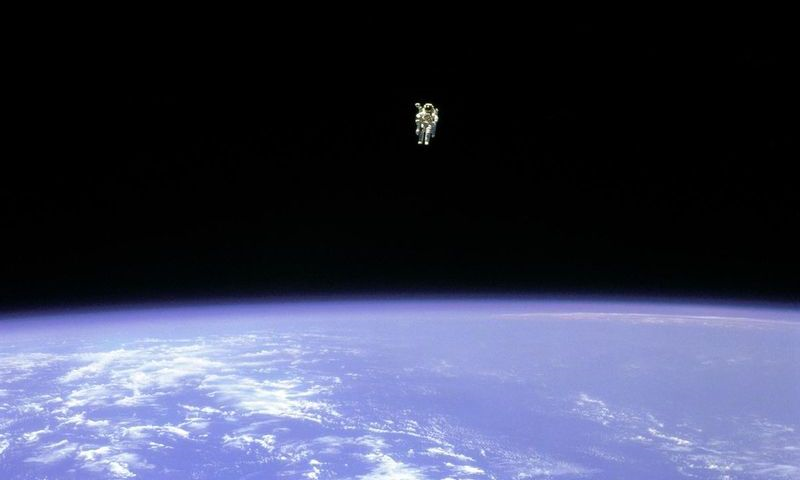

If you are an adult living in Seoul you can travel to most parts of Seoul, but not to all parts. We only go where we go. Sometimes I go to a new neighbourhood to visit a recommended restaurant or shop, but I need to commit to that decision. People who live in Gangbuk, the district north of the Hangang River, Seoul, complain that every time they go to Gangnam it feels like passing through a magnetic field, to the south of the River, while those who live in Gangnam ask, ‘Can there be such a [good] place in Gangbuk?’ While we may install a map on our mobile phones, or recognise how every nook and cranny of reality linked with SNS has developed, or find the hidden stores in Euljiro, Seongsu, and Yeonhee, the gap between the map and reality still exists. Of course, they are not actually empty but there is a place that does not exist for life even though it is right next to you.

In the early 2010s, I worked as a night guard at Seoul Square across from Seoul Station. I worked there for a short period of time, but I walked around whenever I had time. A few years later, Seoullo 7017 opened, and suddenly there was this hip place and cultural complex Piknic in Sowol-ro. I often walked around this area, even after I quit the night guard job. I strolled from Baekbeom Square to Namsan Library, crossed Seoul Road to Piknic, and thought about my days as a night guard while looking out across Seoul Square. However, I never went to Dongja-dong, even though it is located between Seoul Station and Namsan Mountain, near Seoul Square. I did not know the name Dongja-dong, nor the fact that there was housing for the homeless in this area.

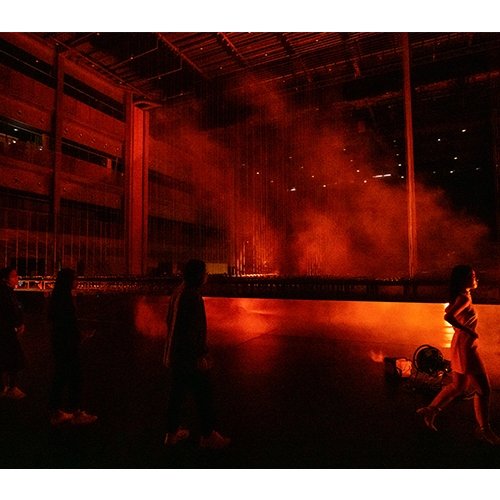

Red Flags

After seeing Lee Bul’s exhibition ‘Beginning’ at the Seoul Museum of Art I walked through Jeongdong-gil with a friend. There was time left until evening, and my friend asked if we could go to Dongja-dong. He said he was curious about the redevelopment of a Dongja-dong homeless shelter he had read about in a newspaper. When I checked, it was familiar in there neighbourhood. ‘Is there a homeless shelter here?’

A shelter is often the final port of call for people with no place to go to, offering housing below the minimum standard. Although the environment is so poor that it is registered as a ‘dosshouse’ under ‘JiOkGo’ (Korean acronym of the basement room, rooftop house, and Goshiwon--tiny accommodations for students), it serves as a safety net to prevent the poor from becoming destitute. Sometimes, they can even serve as social footholds.

Dongja-dong was underdeveloped, but it was not that different from any other neighbourhood. However, it was unusual that each house should be displaying a red flag. There was a warning on the wall not to damage the flag because it was for the vulnerable. We thought the flags were intended to protest unfair redevelopment. Wouldn't it be an excellent sign of demonstration if red flags filled the alleyway in 2021?

But it was not. No, I do not know whether to say no or to say yes. Let's briefly summarise the situation of Dongja-dong. Dongja-dong was selected as a public housing project district by the government in February 2021. Landowners and landlords opposed the government's decision. What they want is private developments. The reason was simple: they bring greater financial benefit. They argue that land and buildings are private property.

So the red flag has been hung by landowners and landlords. It feels like something is reversed -- wasn't the red flag a communist thing? That's the situation anyway. What is important is that those in the shelter, who are actual residents of Dongja-dong, are now alienated from the local community. Most tenants are likely to lose their homes and to be evicted if the area is developed by the private sector. On the other hand, around 10 per cent of the owners live in Dongja-dong. Owners sometimes receive a high monthly rent from those occupying these homeless shelters, unable to pay a lump sum. According to statistics, the average rent per square metre of a dosshouse is 55,318 Won, well above the average monthly rent of 11,939 Won for apartments in Seoul. In many cases, the dwellers receive housing aid from the state, and the owners hope to exploit this to their advantage. This is called the poverty business.

If you search in the Dongja-dong homeless village, you will see conflicting points of view. One side claims to guarantee the survival and housing of residents in dosshouse villages. The other calls for the chance to achieve great success in real estate, investment opportunities and to halt the infringement of private property. Some blogger hashtags are as follows: #DongjadongDosshouse #BecomeABillionaireByAuction

The Philosophy of Tourists

The Japanese philosopher Hiroki Azuma published A Philosophy of the Tourist in 2017. ‘What philosophy do tourists need, those who are neither travellers nor pilgrims’, one might think, but that's what Azuma was aiming at. To briefly explain the philosophy of tourists, this book notes, a light approach meets coincidence, and these coincidences open the possibility of solidarity. Speaking of which, this becomes too simple, but it is a philosophically and politically complex and sensitive issue. Hiroki Azuma published the ‘Fukushima 1st Nuclear Power Plant Tourism Plan’ before publishing A Philosophy of the Tourist, and he was severely criticized. As the title suggests, the book calls to turn Fukushima into a tourist destination. One can guess the nature of the reaction without even attending to the details of the criticism. Suppose someone suggested making Jindo Port a tourist destination in memory of the Sinking of MV Sewol… However, according to Azuma, we are already practising this brand of tourism. Parks, museums, and tour programmes exist on sites of historical tragedies and disasters, such as Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Chernobyl, Gwangju. Thousands to hundreds of thousands of people visit these sites each year. It is just that the word for travel to these places is one of an entirely different implication to that of tourism, such as memorial, memory, and pilgrimage. So maybe there is a language problem here, and language limits our thinking. A gap between the frivolous associations with tourism and the solemnity of mourning -- it is this divisive attitude that Hiroki Azuma’s book provokes. It is impossible to meet the case in real terms from the existing perspective; the memorial fetishizes tragedy. The visitors see only what they want to see. On the other hand, tourists with a much lighter attitude ensure people encounter events through unexpected routes, like a kind of flâneur.

Of course, this is a somewhat conceptual and philosophical story. It is not known which will actually happen or which will be more meaningful. However, when I went to Dongja-dong, I remembered Hiroki Azuma's philosophy of the tourist. I went there with a light heart, but I met with an unexpected place and learned things I didn't previously know. Isn't this what he means by coincidence and solidarity? It is like discovering hidden spots on a map, and encountering hidden reality. Azuma said he was surprised when he visited Chernobyl and Fukushima that people were still living there as if it was ‘normal’. The daily life of people who experience the real smells, volumes, and bodies different from those encountered in the media made him realise that tragedy can happen to anyone and that they are no different from us in spite of physical distance. Richard Rorty wrote in Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, ‘We must constantly strive to expand our sense of being as much as possible’, adding ‘This is a process we must continue. We must try to find marginalised people, those we still instinctively think are “them” rather than “us”. We should try to pay attention to our similarities with them’.

1 Hiroki Azuma, Genron 0: A Philosophy of the Tourist, trans. Ahn Cheon, Seoul, Luciole, 2020, p. 74.