The cover of SPACE No. 31 (June 1969)

Although private housing projects aren’t always under the direct influence of the political and social currents of the time, they are undoubtedly informed by philosophical and ideological influences, joining an explicit yet intimate artistic will with an owner’s preconceived ideas. Given that Villa Savoye (1931) and Vanna Venturi House (1964) are high points in Modernist and Postmodernist design respectively, they can be used as critical anchors from which to ponder the evolution of residential projects over time.

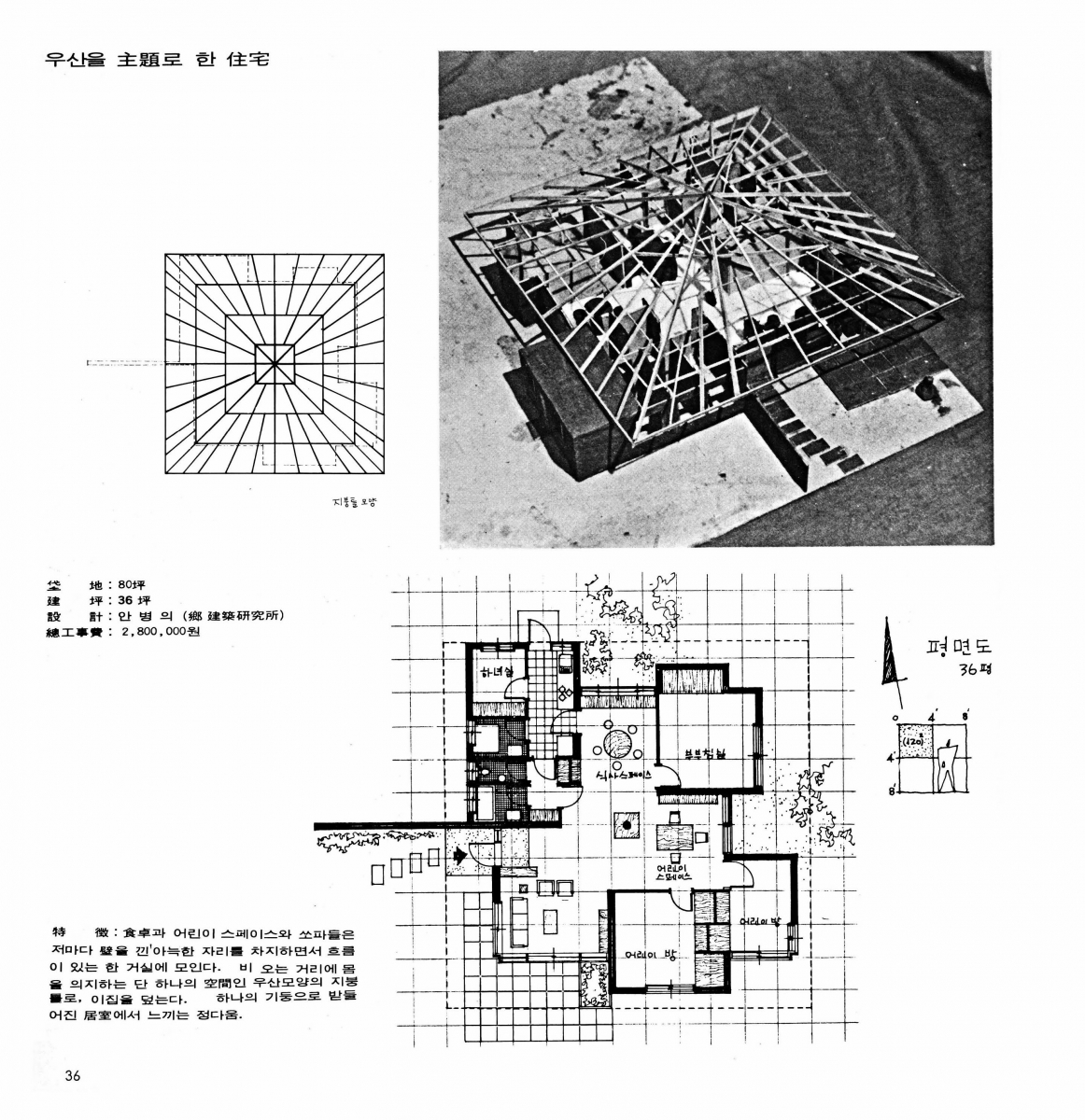

In this regard, ‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’ (covered in SPACE No. 31 [ June 1969]) by the architect Byung-ye Ahn, is a singular project crafted under the national construction boom of Park Chunghee’s administration, and the subject of our attention in this feature.▼1 Please note as a disclaimer that personal preference might have influenced the selection of the project. As a matter of fact, this project can be easily overlooked as it is covered on just one page amidst 20 other residential projects in the same issue. Nevertheless, our attention lingers as the building is subtly misaligned in terms of its modernised floor plan and a roof structure that resembles an umbrella—just as its name suggests. How naive and yet bold a name can be! It stands out among other projects. While houses are typically named after their owners’ family name, such as ‘K house’ or ‘Chairman Hong’s Residence’, this project explicitly underscores the architects’ intention through its name; ‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’. In addition, an amiable sentiment is expressed in the project descriptions of brief paragraphs, communicated in a humane and warm tone.

‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’, SPACE No. 31, p. 36.

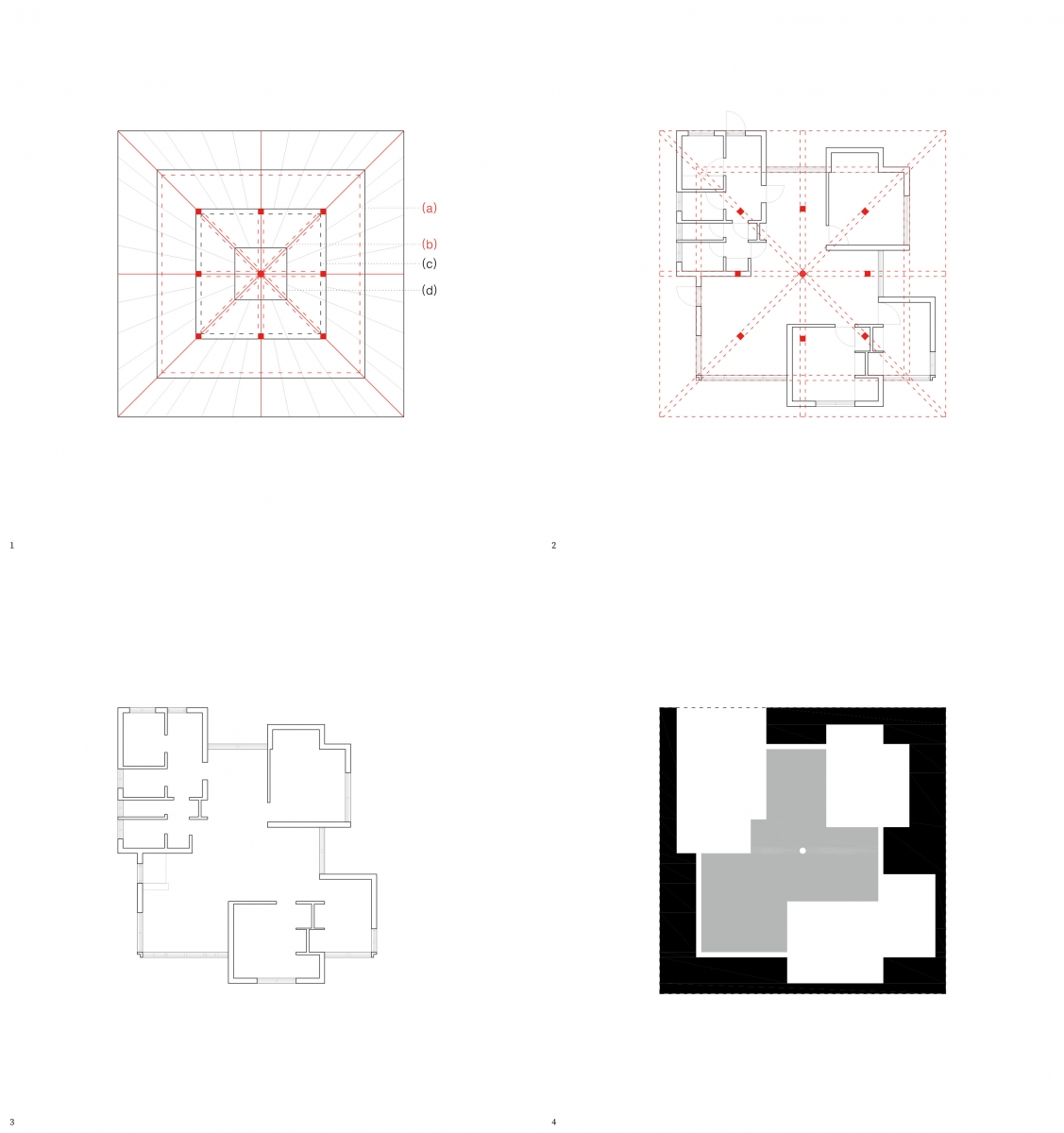

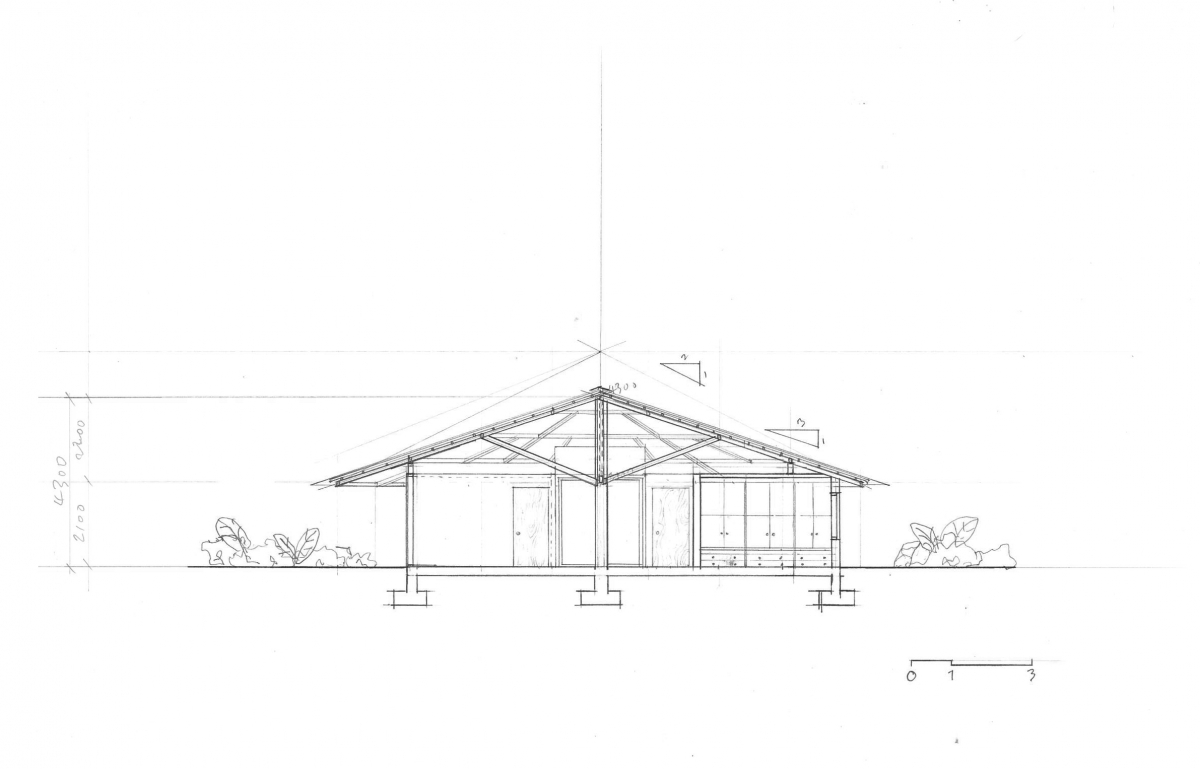

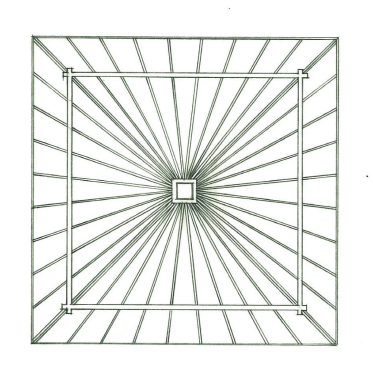

This house has an area of 35-pyeong with a square roof of approximately 13 × 13m (44 × 44ft). Provided that other detached houses in SPACE at that time were about 80-pyeong on average, it can be regarded as a rather small-scale project. This type of project seems to have been determined through the architects’ interest in ‘working-class homes’ but it also seems to be trained upon achieving the best method of applying an umbrella structure.▼2 Unfortunately, it is likely that the plan has never been realised, given that the project was not covered in any issues of the same year or beyond and the photos during a series of studies show slight differences, which only fortifies such speculation. According to A History of Residing by Park Cheolsoo, the ‘a housing type for cultural house’ and a ‘French-style house’ were in fashion between the late 1960s to 1970s, with a huge increase in the number of apartment buildings impelled by government policy at the time. This prevailing sentiment might have inspired the architect Byung-ye Ahn to design a house on a smaller-scale.▼3 One of the interesting points of note at the time can be found in a survey of citizens’ housing preferences; the majority prefered sloping roofs made of baked gi-was, cement gi-was,and asbestos slate gi-was.▼4 Those roofing styles are likely represent wealth. Most houses featured in SPACE around the time are constructed in reinforced brick walls with sloped gi-wa roofs on top of timber trusses, and the main characteristic noted in these houses is that the shape of the roof is subordinate to the wall module due to the characteristic of the wall structure, so usually, the floor plan and the roof shape are the same. Indeed, the ‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’ stands out at a time in which the ‘French-style house’ was the governing trend. Perusing the architect’s sketches on the ‘roof frame shape’, the geometrical integrity of the mathematically arranged members is distinctive. It seems to connect the eight structural members to the central pillar like an umbrella, lifted at the centre of the roof while gradually reinforcing the increasing gap in between. It is suspected that the second horizontally-arranged rectangular structural member on the roof periphery (a) functions as beam that supports the roof, and it is also concerived as a support for the wall that borders the interior and the exterior space. The visible diagonal members when unfolding the umbrella are in use, whether as direct support or as indirect support through horizontal members such as beams. Although both options are credible, the latter might hinder a more intuitive experience of being under an umbrella as it sections off the structural members. Therefore, it is highly likely that each member is supported directly as a gentle slope might lack in structural integrity. However, it is too early to draw conclusions as photographs of study models show the diagonal members on top of the horizontal members. Given the fact that added horizontal members do not have any supporting functions as horizontal members nearest to the pillar (d) or in the architect’s sketches, as well as the fact that the architect placed a unique emphasis on the spatial sense of the umbrella, it is assumed that the umbrella structure has been employed in a literal fashion. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Structure concept of truss (drawing: Sunwoo Uk)

Figure 2. The relationship between the roof and the plan (drawing: Sunwoo Uk)

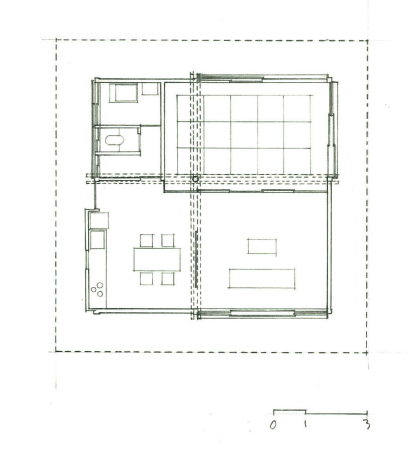

Figure 3. Plan layout with columns removed (drawing: Sunwoo Uk)

Figure 4. Changes in the depth of the eaves according to spaces (drawing: Sunwoo Uk)

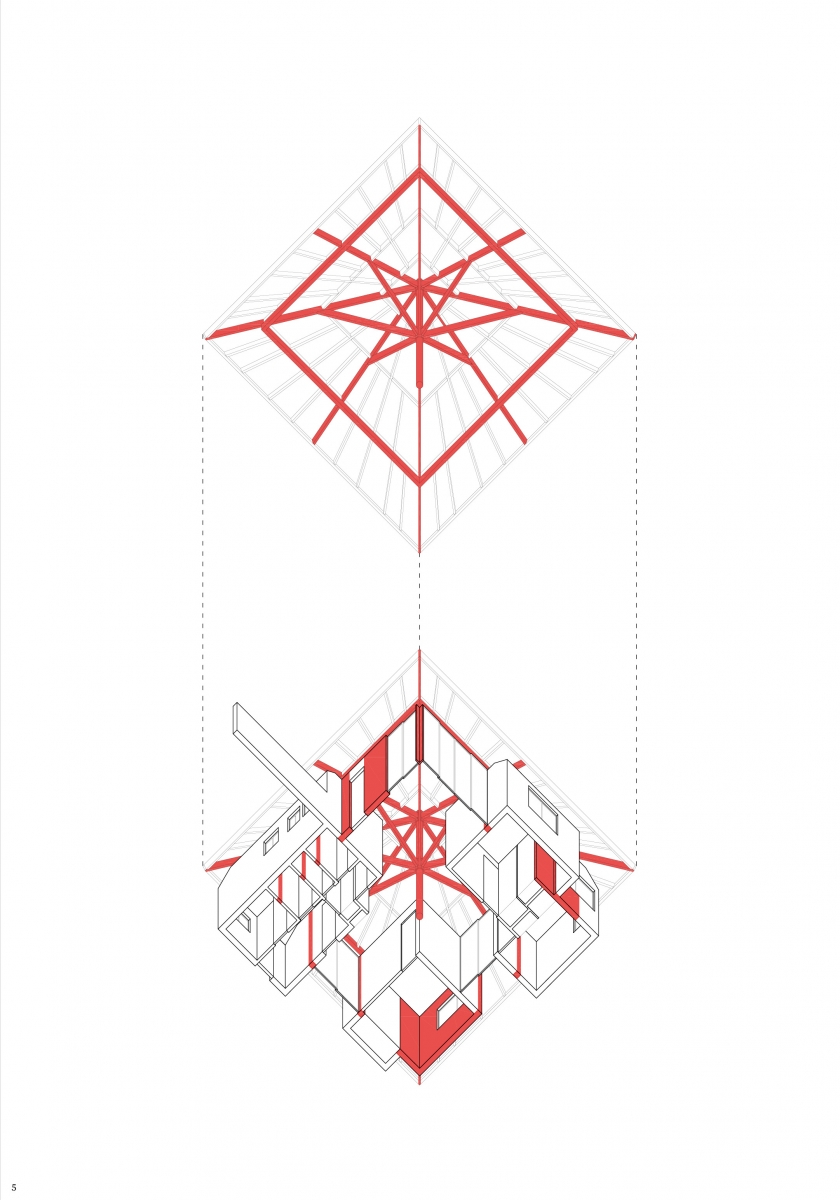

Figure 5. ‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’ axonometric (drawing: Sunwoo Uk)

Figure 6. Cross-sectional view of ‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’ (drawing: Suh Jaewon)

When looking at the project, one cannot help but think of the Umbrella House (から傘の家) built in 1961 by the Japanese architect, Kazuo Shinohara (1925 - 2006).▼5 Despite the eight year gap between them, this comparison establishes a better understanding of Byungye Ahn through work using the same motif. Both houses are very similar in that they have a square roof with a point in the middle, but Kazuo Shinohara’s house is slightly smaller (10 × 10m) than Byung-ye Ahn’s. Above all, the way this house supports its roof is different: in short, Byung-ye Ahn’s house has an umbrella stick, while Shinohara’s house does not have a pillar that supports its roof. (Figure 7, 8) This does not mean that there are no pillars at all, but the pillars exist away from the center and only support the beams passing through the air in a cross form at the intersection. In other words, while ‘Umbrella House’ seeks Japanese characteristics by deconstructing textual meanings and borrowing from the mechanics of traditional Japanese paper umbrellas (karakasa), the ‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’ symbolises an existential aim, to interpret the fluctuations of daily emotions with sensitivity.▼6 This is a literary attempt to translate the meaning of an umbrella through a spatial terminology derived from the Korean literary sentiment of ‘amiability’ – meaning the only space to rest one’s body in pouring rain – as written by Byung-ye Ahn in his project descriptions.

Both architects took different approaches tio their floor plans under the symmetrical roof. ‘Umbrella House’ maintains a perfect square volume, while ‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’ is an incomplete asymmetric volume. (Figure 4) Of particular note is that Byung-ye Ahn’s house possesses a different roof shape and plan, and it is difficult to imagine the shape of the roof once the pillars are removed from the plan. (Figure 2, 3)

Figure 7. ‘Umbrella House’ truss floor plan (drawing: Suh Jaewon)

Figure 8. Floor plan (1st) of ‘Umbrella House’ (drawing: Suh Jaewon)

It comes to me as a typical Korean sentiment, one that shuns being tied to anything. Koreans prefer an open ending rather than a closed ending, and often say, ‘There is no virtue in being squared up’. There are chapters here entitled ‘Let’s Live Optimistically’ and ‘Charming Rather than Pretty’, all collated in Byung-ye Ahn’s 1996 essay collection The Snail and the House..., and these notions help us to understand the background to his projects. It doesn’t come close enough to explaining the contradiction between the strict roof frame and self-deprecating floor plans, but this is quite interesting from a postmodern point of view. If this is as intended, it will be classified as ‘design’, but if it is not, It remains a difficult task for us since it can be interpreted as inmmaturity. Scrutinising all of this very closely, we find traces of not only Le Corbusier, but also Mies van der Rohe, as well as Frank Lloyd Wright and Alvar Aalto. He was a 43-year-old architect when he designed this project. It makes me reflect upon my own work, imagining him lighting up a cigarette at 3 a.m. while sitting in front of his drawing board, finding his way as a young architect. I was cautious about writing this article, one focused on the work of a senior architect who practicing long before I was born and based on the little data gleaned from a one page report from 1969, even though I have conducted in-depth observations and investigations. Only can he who has passed away can answer whether the description given above is true. Nevertheless, the reason I was able to author this essay with confidence was down to the question of whether the history of our modern and contemporary architecture has been neglected and flattened. One day, if the day comes when students bring the ‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’ to class for use as a housing design case study, this article will grow in meaning. (written by Suh Jaewon / edited by Kim Jeoungeun)

A view of the dining area from the living room of ‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’. 1:30 model (production: Jun Joonho) ©Suh Jaewon

A living room viewed from the dining area of ‘A House Inspired by an Umbrella’. 1:30 model (production: Jun Joonho) ©Suh Jaewon

In our next issue, Cho Hyunjung will cover ‘Architecture, Sculpture, Poem and the Public’, which first featured in SPACE No. 93 (Feb. 1975).

1. The architect Byung-ye Ahn was born in 1927 in Yonggang-gun, Pyeongannam-do, and died in 2005. After graduating from the Department of Architecture at Seoul National University in 1952, he worked at the Ministry of Transportation’s Facilities Bureau, Kim Chung-up Architecture Research Institute, and the Korea Housing Corporation. After studying architecture in the Netherlands, he returned to Korea and built up Hyang Architects designing about 50 houses. He worked at the Los Angeles design office in 1975, returned to Korea three years later, opened an architecture practice again, and designed the Hyatt Regency Busan. He served as the principal at the Kim Chung-up Architecture Research Institute, but the exact term of this position is unknown. Byung-ye Ahn, The Snail and the House…, Jeongwoosa, 1996.

2. In his solo exhibition held in March 1969, Byung-ye Ahn defined social life as ‘stress’ and asserted his vision of the home as a shelter. Of the houses he exhibited, those of 15-pyeong and 24-pyeong were included. See ‘Growing House, principles for extension projects found in housing exhibition by Byung-ye Ahn’, Joongang Ilbo 13 Mar. 1969.

3. In ‘Housing Theory’, Byung-ye Ahn reveals his skepticism of the apartment as residential unit, which was then a pioneering residential type in Korea, believing it to be an unpleasant space that renders the human life robotic. In the conclusion, he envisages the conundrum by referring to the raccoon’s den or the bird’s nest. Byung-ye Ahn, ‘Housing Theory’, Architecture 10.23 (Dec. 1966), pp. 4 . 9.

4. Park Cheolsoo, A History of Residing, ZIP Publishers, 2017, p. 44.

5. See ‘Kazuo Shinohara Houses’, 2G 58/59 (Sep. 2011); ‘Kazuo Shinohara’, JA 93 (Spring 2014).

6. Both architects happened to release articles almost simultaneously: ‘Housing Theory’ by Byung-ye Ahn (aforementioned thesis, 1966) describes more realistic architectural ideas while Kazuo Shinohara’s ‘Jutaku-ron’ (Shinkenchiku 42.7, 1967) explores architectural ideals in detail.