Upon seeing a work of Vietnamese architecture, one notes its many historical connections with Korea. Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and Chinese characters have had a significant influence on broader society and culture. It has much in common with the design features of the colonial period through various dynasties, the Civil War, and that of the rapid economic development of the modern period. The Vietnamese architects creating their own architectural foundations on such layered and interconnected histories can be uncertain of their identity and face unexpected challenges. With the current state of Vietnam’s architecture in mind, I had a conversation with Dam Vu, the co-principal of Kientruc O.

interview Dam Vu (co-principal, Kientruc O) × Park Changhyun (principal, a round architects)

Park Changhyun (Park): The name of the studio, ‘kiên trúc’, means architecture in Vietnamese. As you use the word ‘architecture’ in the name of the studio, the structural concepts you want to implement must be clear. I wonder what topic you work on in architecture with the meaning of ‘O’?

Dam Vu (Dam): The word ‘kiên trúc’ is understood as partly the name of our studio and partly in the sense of its true meaning in our language. The letter O implies a figurative meaning rather than a simple letter. It is a perfectly incomplete circle. As expressed in the studio logo, it seeks to convey what is extensive, universal, but also essential and original, through architecture.

Park: Does the expression ‘perfectly incomplete’ mean you experience a kind of insatiable appetite for architecture? If so, how would you characterise this appetite specifically, and what are you doing to feed it?

Dam: The perfection we seek is natural and humanly sentimental, one which can be found in the true nature of things. To this end, we discern the core meaning of the project and then set about finding the most natural way of building the architecture. I devote my time to this process and to demonstrating a certain caution. The design process always weighs up whether we will find and infer the architectural meaning of the project from external elements or express what is already being shown. In general, when a project becomes a reality, it becomes an independent entity with an identity in and of itself. We look at whether the project has the potential to express its own meaning, but do not consider the type or size of the building at the outset.

Park: I think architecture has also entered a turning point in Vietnam, as it has recently grown in economic terms. What are the defining characteristics of the changes this has brought about in the country’s architecture?

Dam: Vietnam extends geographically in a latitudinal direction. Vietnamese architecture is under the influence of every region of the country, and local traditional elements are still preserved and used. In particular, Hồ Chí Minh, located in the south, coexists with an architectural heritage derived from various historical periods and phases in modern architecture. In a broad sense, Vietnamese people have openness and flexibility, but each has region has its own defining character and tone depending on how they live and where they live. I think this comes from the relationship between the human and natural worlds. In line with Vietnam’s extensive urban development, a great many changes and increased rate of progress has developed in order to adapt to and follow general trends. But there are also traditional elements that are ignored and forgotten in the process. For us, tradition is an important reference point when working on new things and when analysing what is happening around us.

Park: Is there a traditional element of particular interest to you?

Dam: Yes, the construction of Đính, traditional houses, and of Hue royal architecture, which is mainly located in northern Vietnam. These buildings have their own architectural principles and are always built to exist in harmony with nature. In terms of the essential meaning of architecture, I think public architecture or traditional houses in the north are at the highest level—their spatial proportionality, purity, and symbolic expression are excellent. The size of the space consists of tâm, which serves as a traditional module that corresponds with Vietnam’s typical body proportions.

Park: Please give me a detailed explanation of the aforementioned Đính. What is purpose of these buildings and what are its architectural features?

Dam: The main purpose of Đính is a place of worship, but it can also be a daily gathering place, a court, a concert hall, etc. While performing many functions in the same space, the original nature of the space remains untouched by external influences. The same is true of traditional houses. The large space within the single solid structure houses is an adaptable and suitable space in which single-generation and multi-generation families can live together. Adding a room to the house does not affect the harmonious beauty of the house’s structure, order or space. This flexibility and adaptability is actively expressed in the structure because they can be assembled and dismantled for transport to other regions in Vietnam, and reused in other regions and contexts. In Vietnam, the natural environment varies from region to region. To live on land, its people must adapt to the climate of the area and coexist with nature. At the national level, we share some common characteristics, but there is regional diversity in which climate is a determining factor, and as a consequence the architecture responds to these differences between different regions.

Park: Along with recent economic changes, social changes are likely to be experienced due to the present Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) global pandemic. What do young Vietnamese architects think about this situation?

Dam: According to our observations, housing and residential building projects have not changed much under COVID-19. The primary pressures that affect architecture now are how people perceive their lives and how they live them. Many agonise over how to live, whether to pursue a slow, well-being-oriented life, and this change is revealed through client needs and building users. People are actively discussing and expressing the need to prioritise the quality of life and moving away from viewing architecture as more of a material possession.

Park: These changes are not yet widespread in Korea, so I envy this consideration. Therefore, how is Kientruc O moving with the flow of Vietnamese architecture?

Dam: Architecture is a human product . Inevitably, it is linked to the geographical and social diversity of the region in which it is located, and its endurance, along with the practices and expressions of the generations depend on the conditions of the place. However, even if the wider societal situation changes, the essence does not change. The East is considered to have mysterious potential, and I think this is because of the general principle of operation. Asia is becoming a centre of attention and intrigues in many ways, including in terms of its contemporary architecture. I’ve been thinking about the ‘behavior signal’ theory for a long time, a concept strongly linked to human civilisation. This seems to be a broad concept, but it’s not a matter of nature, it’s a vital imperative for humans.

Park: How would you describe the concept of the ‘behavior signal’, which you state above?

Dam: When we look at flowers we experience aesthetic appreciation. We look into the reasons for making us feel this sense, how it is developed, by analysing the senses and their properties. We are often surprised by the results. It is possible to appreciate flowers through their colours and subtle scents, even though you have no theoretical knowledge of plants. It’s a ‘behavior signal’ that experiences and appreciates beauty without any preconceptions. There is a similar phenomenon created by humans in our human world. Aesthetic refers to a universal feeling regardless of culture and context.

Park: Let’s move on to talk more specifically about the project. I am particularly curious about House 304, which was completed in 2015. Where is this building located?

Dam: The house is located on a long, narrow plot, and the exterior is simple, considering its surroundings. At the heart of this house is the happiness and serenity of its residents. In other words, the focus was on how they would interact with the spaces over the course of their daily lives.

Park: Are you saying that the focus is on the house itself rather than on its relationship with the surrounding environment? We are deeply concerned about the relationships structures strike up with their neighbours and spend a lot of time working on this topic. Do you think the concept of the neighbourhood affects one’s quality of life?

Dam: Your question is very interesting, and you are absolutely right. However, the micro-context is very different for each site and this diversity gives us flexibility in our design. House 304 is located in an area with height restrictions and regulations on building setback lines, so as to create an orderly neighbourhood. We wanted to create a house of a high standard that would inspire greater diversity and interest among the homes in the neighbourhood by focusing on the building itself and enriching its architectural characteristics. It is hoped that this will begin to resonate throughout the area over time. It’s

one thing that belongs to the whole area, and it’s getting better.

Park: I think there is a distinctive architectural feature in the form of the rectangular shape of land often seen in the city centres of Vietnam. One of the most significant things that determines the price of a rectangular plot in Europe is the width of the building facing the road. What about in Vietnam?

Dam: Yes, this is a typical type of Vietnamese urban structure. The façade of the building has considerable economic value and gives small businesses the opportunity to use or rent. Even if it is the same area, it has higher economic value than when it is in a small alley. However, this type of housing is considered one of many new types, such as apartment blocks, double buildings, and complex buildings.

Park: In terms of Vietnamese city house, there is often a narrow, long but also high-rise Nhà ống. House 304 has the area of 3.5×12m, roughly similar to that of Nhà ống, so what was important when designing a house under these conditions?

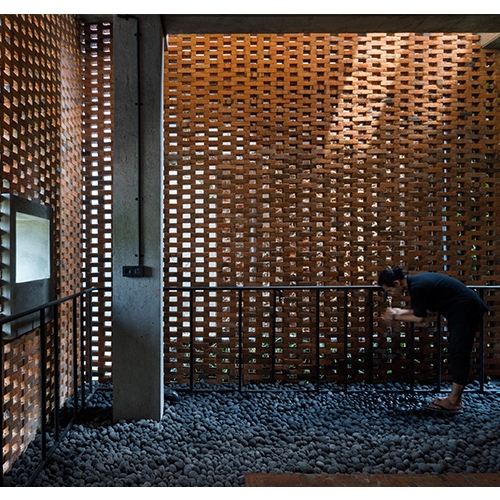

Dam: Building regulations are applied according to designated areas in Hồ Chí Minh City because of the typological diversity of the long and narrow residential tube house. In particular, there are regulations on building regression lines, the number of floors, and the height. The site of a tube house is often too limited and narrow. In general, residents want to supplement these land restrictions by securing a large available area, but this not only prevents communication between families but also lowers the quality of light and air. Usually, a tube house has one or two sides exposed to the outside. One side faces the road and the other side faces the site’s perimeter or a neighbouring house. When the building area is maximized, stairs that divide the front and back of the house are usually placed in the middle of the house, which makes the house dark and poorly ventilated. As a result, this spatial stratification reduces human connection between people living under the same roof and further distancing themselves from each other.

Park: Japan also has a lot of these tiny houses. When I see tiny houses in Japan, I think there is a tendency to focus on the composition and spatial transitions between interior spaces, including movement and experience. What is the difference between the Nhà ống in Vietnam and tiny houses in Japan?

Dam: I think nature and human are in a symbiotic relationship. Vietnam is a hot and humid tropical country, and as such interspaces and natural ventilation are considered important architectural factors. Even if there are similarities between Asian countries, from a broader perspective, the friendly nature of the Vietnamese has lead to the simple, original, perhaps rustic and honest personality common in Vietnamese tube houses. As the city developed, the type of rural garden housing became narrower and longer to suit the new urban environment. This development is evident in Hà Nội and Hội An. Traditional garden houses usually consist of two levels of wooden structures, which serve to keep the whole area in order without harming it. The opening in the middle of the house helps with natural ventilation, provides a sense of openness in long and narrow areas, and serves as a chimney to let air out.

Park: As you go upstairs, the floor area decreases, and each floor has an external terrace, which seems to bring variety to the simple plane. Functional spaces are arranged one floor per floor, separating each space, but all floors are connected as one through indoor void and exterior terrace. It also seems that two layers devise a room. Is the relationship struck up between the front of the house and surrounding neighborhood valid?

Dam: Setting buildings back from the boundary line is the result of agonising over details and studying elements in order to create shade and space between them. Instead of installing vertical louvers, each layer was set back using shade made by planting. In a way, this approach is smoother and more natural and creates positive energy for the residents. On the other hand, it effectively opens up the interior space while promoting individual connections with the exterior environment.

Park: As I mentioned earlier, the internal void seems to play a very big role in this house. A corridor circulating the void surrounds and connects each layer into one movement.

Dam: House 304 is a good example of how a space of natural ventilation and natural light can be devised in tropical climates. The key to this house, however, is the way it reconnects people and renews human-natural relationships. This spatial composition is reminiscent of a typical Vietnamese traditional house; a long, single-story structure surrounded by gardens. In a house that is open to its surroundings, residents can connect with nature in a sensitive manner. However, the quality of this space seems to be obscured by tight spaces, skyscrapers and the need to maximize the floor area for functional purposes. The function of the void is similar to that found in traditional two-storey townhouses in Hà Nội and Hội An. However, since House 304 is a four-storey building, it had to gradually increase the size of the void in order for natural light to reach the bottom. In addition, the void was treated as a very important spatial component in which family members could meet visually and physically in all areas of living indoors.

Park: The void is drilled under the circular ceiling on the top floor, and the void circulation space inside the house is exposed to the outside atmosphere without any separate windows or barriers. In particular, the living room and kitchen, which feature the most public characteristics in the house, are located, offering another crossing point between inside and outside.

Dam: The vertical void gives the house a sense of openness. However, the interesting spatial situation of this house is that the traditional horizontal space is gradually readjusted to a vertical space that spreads out into the sky. The opening of the roof allows air to flow naturally into the house, with an automatic glass ceiling system to protect the house from heavy rain. The first floor with a terrace is the place where the experience of horizontal space is the most obvious. The most comfortable space for people is a space composed of shadows, light, wind, and sensory connections to nature.

Assist in interview: Ju Han Seul (Korea University, Department of Architecture)