The cover of SPACE No. 93 (Feb. 1975)

SPACE was launched as a comprehensive art magazine covering various fields from across art and design and throughout tradition and modernity rather than as an architectural journal introducing contemporary architecture. ‘Architecture, Sculptures, Poem, and the Public’, published in SPACE No. 93 (Feb. 1975), a talk by architect Cho Keunyung, artist Oh Yoon, and the art critic Choi Min, elucidates the design ideals promoted by SPACE, which provided public debate to artists from various fields. The talk centred around the mural relief series in the Commercial Bank of Korea (CBK) designed by Cho Keunyung and made by Oh Yoon, Oh Kyunghwan and Yoon Gwangjoo. Of the three branches with murals, including CBK Samgakji, Guui-dong, and Dongdaemun, the only existing building is the Dongdaemun branch (current Woori Bank Jongno 4-ga Financial Center). The building is a simple two-storey concrete structure with no particular decorative features. However, it is not easy to grasp the building’s overall impression, perhaps because of the large mural (3.4 × 32m) attached to the ship-shaped structure at the front of the first floor. The second floor, which is situated above the relief, forms a geometric pattern with deeply retracted rectangular windows which repeat along its length. S-shaped stairs connecting the first and second floors create two cylindrical shapes. Some may feel a temptation to locate the origins of the architectural style of Cho Keunyung, defined by a geometric preciseness, aggressive verticality, and acute angles as noted in the CBK Dongdaemun. As Cho Keunyung’s significant works, such as the JS Building and The Hankyoreh Office Building, were mostly built in the 1990s, CBK Dongdaemun – designed in his mid-20s – is genuinely a valuable reference. In the same way Choi Min describes Cho Keunyung as a ‘functionalist’, emphasising function over signs and symbols, the building barely reveals the touch of the auteur. Instead, the architect’s humility yields the entire façade to a large-scale mural relief of a different colour and texture, arresting the eye. The mural, entitled The Peace, used 1,000 Jeondol squares (traditional bricks) of the same size with 3cm of thickness, to form simplified shapes of figures, mountains and clouds. The relief continues inside the building. This 4 × 6m interior mural took its motif from Tile with Divine Landscape Design in Buyeo. Unlike that of the outer wall which foregrounds the sculptural character of a high relief, the inner creates a picturesque effect by mixing variously coloured and shaped Jeondol with cement. When the Culture and Arts Promotion Act, Article No. 9 (also known as ‘1 percent for art scheme’)▼1 did not yet exist, what was the reason for installing a massive mural onthe front of the building and investing the extra cost? At that time, Cho Keunyung was an unknown architect in his mid-20s, and Oh Yoon and Oh Kyunghwan had just graduated from the art college. This project was made possible because the father of Lim Setaek, their fellow alumni and a member of the Hyeonsil Dongin group (1969), was the head of a CBK. They were known to persuade their friend’s father into creating a beautiful building like Jagyeongjeon in Gyeongbokgung Palace and to be in charge of the building mural project. They worked on the project with Cho Keunyung’s Kiin Architecture (later Kisan Architecture) office in Gwanghwamun, and Yoon Gwangjoo, son of Yoon Gyeongryeol, the master of Silla clay figurine, also joined the project.

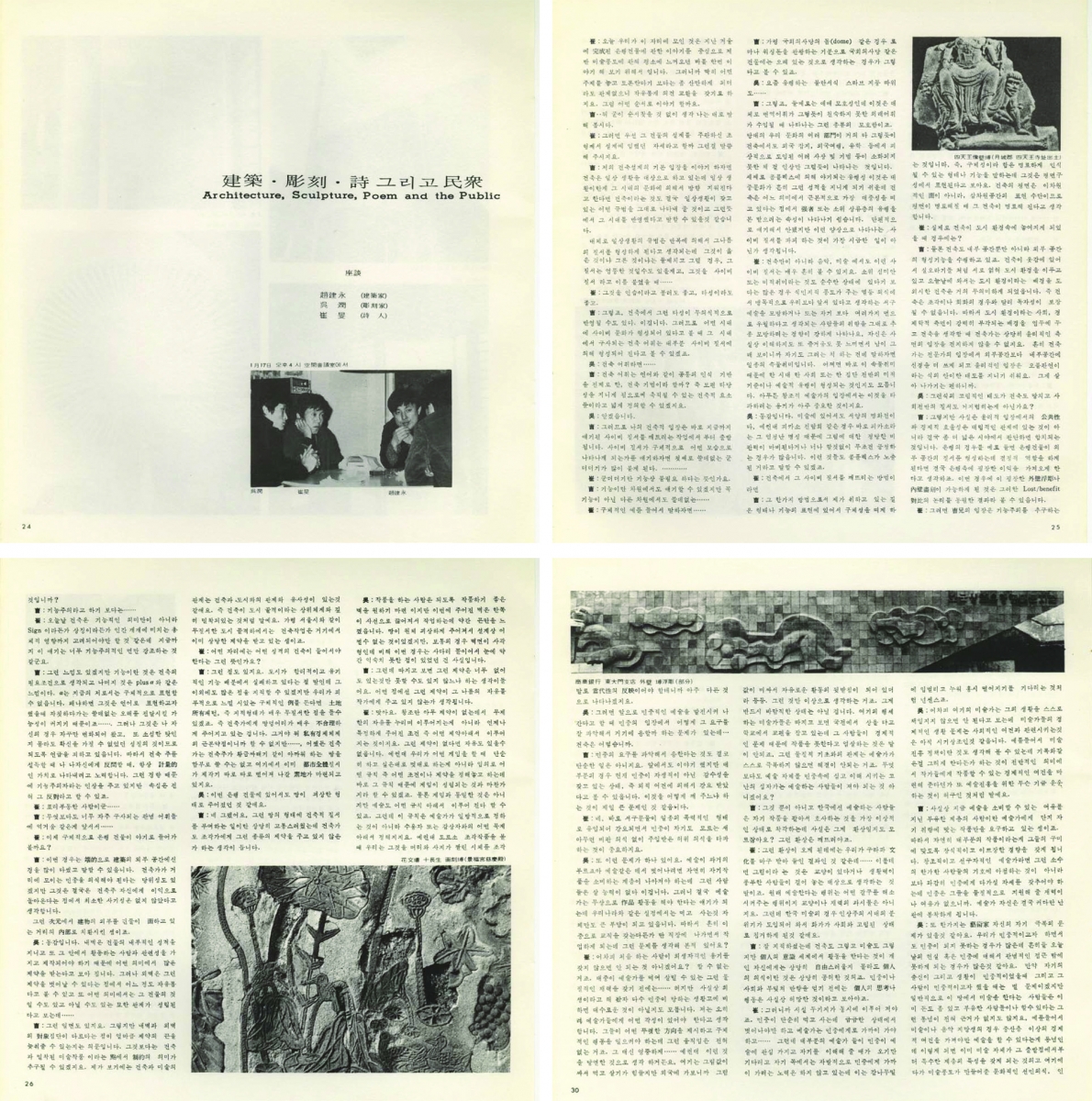

‘Architecture, Sculpture, Poem, and the Public’, SPACE No. 93, pp. 24 – 26, 30.

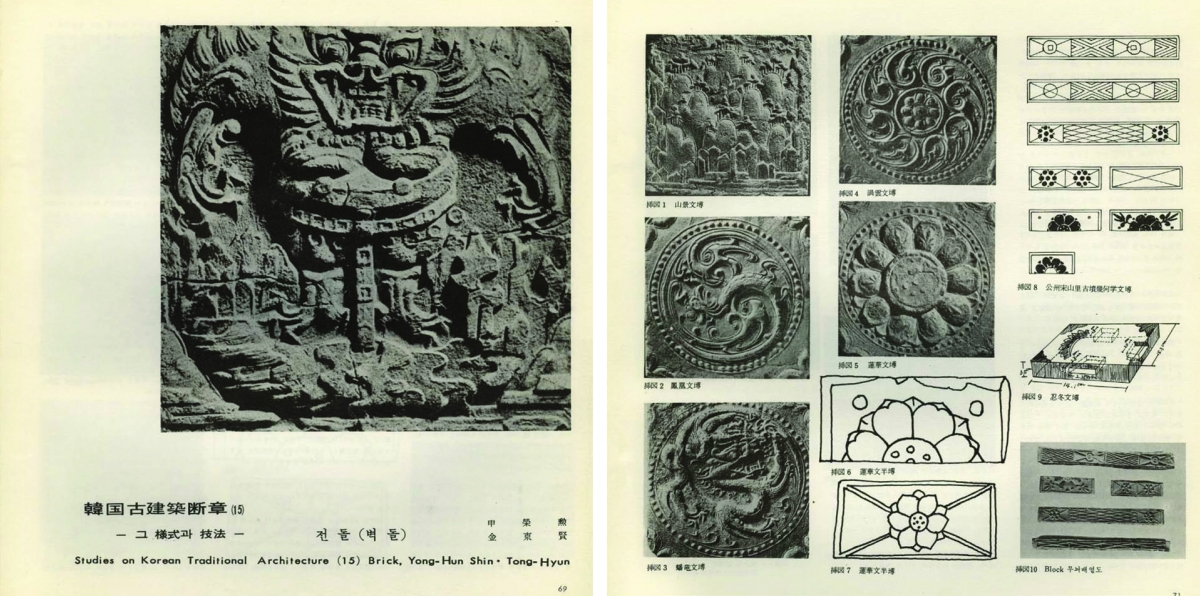

‘Studies on Korean Traditional Architecture (15) Brick’, SPACE No. 49 (Dec. 1970), pp. 69, 71.

The significance of the conversation in SPACE No. 93 can be understood in terms of a pioneering attempt by which progressive artists from across disciplines gathered to discuss the nature of the public and the democratic arts. The participants focused on the public character of the relief. Choi Min concluded that museums are a mausoleum for artworks and suggested that art should pass into the street to meet its public. Of course, it is not the first created in collaboration between architects and artists so far. Several relief works that decorated the rough surface of exposed mass concrete with multicolour porcelain chips were presented in the 1960s, such as on the French Embassy in Korea built by Kim Chung-up (1961, the mural created by Youn Myeungro, Kim Chonghak and Yoo Kangyul), the Oyang Building by Kim Swoo Geun (1962, by Jeong Kyu) and the Sewoon Plaza (1967, by Kim Yeongju). However, while the murals installed in the French Embassy in Korea and Oyang Building complement the architecture in terms of their aesthetic character and formal relationships, the mural of CBK Dongdaemun questions the extent to which art should encounter its public and tell a story; in other words, it raises questions about the democratisation of art and of the cultivation of a popular style. Oh Yoon had taken a keen interest in the murals of Mexican artists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco and was deeply affected by their artworks. It is no coincidence that Oh Yoon formed an art group, ‘Hyŏnsil kwa Parŏn’ (Reality and Statement), with Choi Min, Sung Wankyung, and Kim Jungheun in 1979 and emphasised communication based on realism beyond the cliquishness of modernism. The activity of Hyŏnsil kwa Parŏn marked the beginning of the art movement in the 1980s, and Oh Yoon’s interest was more in the print that could be mass-reproduced rather than the mural. However, for many Minjung Art practitioners, murals were an alternative and political medium that made artwork present in people’s lives, and crucially were not an art made exclusively for the privileged class. Nevertheless, it may be an anachronism to limit the murals of CBK Dongdaemun to forming a direct precedent for Minjung Art. In fact, it wasn’t until the 1980s that the public began to be widely discussed as an active historical subject with the possibility of overthrowing the regime. The keywords that characterise Korean society in the 1960s and 1970s were none other than that of nation and tradition. The emergence of a modern consciousness, including the theory of the Capitalist Embryo and Silhak (Realist School of Confucianism) in the late Joseon Dynasty, excited researchers from various fields, including history and literature. This led to the rediscovery of the traditional masked dance, Pansori, and folk songs, shamanism, folk paintings and crafts. A nationalist craze swept the country, from the ruling clique to the progressives. Kwon Boduerae and Cheon Jeonghwan pointed out the characteristics of nationalism in the 1960s. They explained this with the following: ‘If the Park Chunghee regime combined development theory with that of the nation, the critical forces introduced it as a spatio-temporal coordinate with the ability to expose the injustice of the existing state system through the representation of the “nation”’.▼2 Since its foundation in 1966, SPACE also promoted the discovery and modernisation of tradition and the rise of nationalism. Immediately after its publication of the first issue, features included ‘Studies on Korean Traditional Architecture’ (1966 ‒ 1967) by authors Choi Sunu, Hwang Suyong, and Kim Won-ryong. The ‘Rediscovery of Our Beauty’ (1968 ‒ 1970) series aroused interest in traditional arts and culture, while the essays of architects and folklorists, such as ‘Some Thoughts on Korean Traditional Architecture’ by Shin YongHun and Kim Tonghyun and ‘The Stage of Korean Folk Drama’ of Shim Usung, have had a long-lasting impact. The murals of CBK Dongdaemun using Jeondol can be understood through the continuing editorial stance of SPACE of the ‘discovery and modernisation of tradition’. The fact that Oh Yoon established a brick factory immediately after the mural project and devoted himself to the modernisation and mass-production of Jeondol shows that his interest in Jeondol was not simply a one-off. This interest was not exclusive to Oh Yoon. ‘Studies on Korean Traditional Architecture (15) Brick’ published in SPACE No. 49 (Dec. 1970) dealt with the history and production methods of Jeondol dating back to the period of the Three Kingdoms. The authors, Shin Yonghun and Kim Tonghyun, emphasised the high value of bricks by Park Jiwon, a scholar during the Joseon Dynasty, and introduced Chinese and Joseon literature that explored Jeondol. These documents also became essential references for Oh Yoon’s implementation of traditional bricks. The excavation of the Tomb of King Muryeong in Buyeo in 1971 was a groundbreaking event that imprinted the importance of Jeondol on our cultural conscious, as a kind of conventional brick as well as a decorative building material.

Greater attention to Jeondol held many parallels with the more general disbelief of the time regarding concrete. The most crucial issue in the dispute concerning the Buyeo National Museum (1967), which lit up the Korean architectural world, was whether it was possible to convert traditional wooden structures into the concrete.▼3 In this argument, Cho Keunyung pointed out that ‘As concrete is used in architecture, traditional Korean materials have been ignored, and exterior walls have been formed as foreign and fashionable materials. However, this case is meaningful in that the possibility of bricks has experimented’. Oh Yoon was also looking for an alternative to expensive marble or foreign industrial materials from a traditional outlook. Art historian Cho Insoo paid attention to the fact that Oh Yoon read The Chosunilbo by Kim Hyo-shin, which expressed the opinion that the cement pavement in the Hyeonchungsa Temple is hideous.▼4 Kim Hyo-shin was a Frenchman named Alexandre Guillemoz, who came as an exchange professor to Seoul National University to teach French literature and study Korean shamanism. He defended the beauty of traditional bricks in the article. A few days later, an item that actively agreed wit his argument was published in the same newspaper. Oh Yoon had scrapped both pieces.▼5 While Kim (Guillemoze) praised the beauty of the traditional stone as ‘elegant and simple, delicate yet strong’, Oh Yoon stressed that it was a material that could flexibly change the size and shape of buildings and sculptures, as well as obtain various colours and effects depending on the temperature and materials at which the bricks are baked, rather than through its appearance. The person who longed for new construction materials that were both ‘Korean and modern’ was Kim Swoo Geun. In the 1970s, he marked the beginning of the ‘Brick Age’ along with the completion of the SPACE Group of Korea Building (hereinafter SPACE building). As a human-scale building in brick, the architect conceived of his unique style beyond the monumental structure of exposed concrete, a characteristic of Kim Swoo Geun’s architecture in the 1960s. His ‘Brick Age’ concerned the search for traditional practices not only in architecture, but also in arts, crafts, folklore, and literature. The black brick used in the SPACE Building was provided by Kim Younglim, a master artisan of traditional roof tiles and bricks who founded the Hankuk Tohyong (1966) and devoted her life to researching traditional tiles and bricks. Kim Wonsuk, who participated in the construction of the SPACE Building, noted that bricks derived from the soil are in harmony with nature and act as a friendly material suitable for human-scale constructions. Brick walls of unique textures are arranged ruggedly to maximise the unexpected characteristics of the building.▼6 SPACE Building is often discussed as a decisive opportunity for architects to change their interest in traditional architecture from ‘form’ to ‘space’. However, it is also worth noting that the building contributed to the theory of tradition in terms of its ‘materials’, and that the discussion was developed in the spirt of exchange and collaboration between artists encouraged by the magazine. That is the significance of the talk in SPACE No. 93. (written by Cho Hyunjung, professor at KAIST / edited by Bang Yukyung)

In our next issue, Hyon-Sob Kim will cover ‘Two Architectural Exhibitions’, which featured in SPACE No. 59 (Oct. 1971).

1. A Law that obliges the expenditure of an amount at a particular ratio (1 percent) of the construction cost of the building on the installation of artworks.

2. Kwon Boduerae and Cheon Jeonghwan, Questioning about the 1960s: The Cultural Politics and The Intellectual in the Park Chunghee Era, Seoul: imagine1000, pp. 289 ‒ 290.

3. A controversy concerning the museum building and the main entrance design resembles the structure of Japanese shrines and Torii gates. The plan was partially revised, and the museum opened in 1971.

4. Cho Insoo, ‘Oh Yoon Achieved Minjung Art’, Oh Yoon: People Around the World, People in Neighbourhood, Seoul: Hyunsil Munwha, 2010, p. 35.

5. Kim Hyo-shin, ‘Bulguksa Temple and Hyeonchungsa Shrine’, The Chosunilbo 21 October 1973; Heo Sul, ‘The Transmission and the Use of Bricks: After Reading ‘Bulguksa Temple and Hyeonchungsa Shrine’ of Alexandre Guillemoz’, The Chosunilbo 3 Nov. 1973.

6. Kim Wonsuk, ‘The Thoughts and Creation of the Brick Culture’, Architecture 41.8 (Aug. 1997), p. 4.

Present view of the Commercial Bank of Korea Dongdaemun