A Museum Beyond Heritage Preservation and Tourism

We applaud the objective of the museum ‒ introduced in the competition brief ‒ to become ‘a “dynamic museum” that can sustain evolution and growth by accumulating and producing a wide range of content through linking its archive, exhibitions, education and research activities’, as it embraces the ambiguous, double-sided character of the architectural profession as an agent of cultural production on the one hand and as a creative profession on the other. We appreciate the ambition of the Korean Museum of Urbanism and Architecture (KMUA) to become a place for more than the display of artefacts, historical heritage, and the production of cultural identity, in its choice to support the quality of spatial design, education and experimentation. This creates a cultural institution that does not only add a new icon to the local architectural landscape but might also give a boost to the architectural creative economy in general.

The implementation of an ‘institutional heavyweight’ like KMUA, however, has significance that exceeds architectural value. Large cultural institutions have the potential to generate new economic impulses and reconfigure established power relations. The choice about where to implement the new museum therefore also has strategic significance from an urban planning perspective. The new museum can for example be employed as a tool to improve the image as well as the livability of a‘young’administrative city like Sejong by diversifying the local economy and broadening the resident structure. Moreover, improving the attractiveness of Sejong with new cultural programmes might help to overcome the imbalance in regional development. Ignoring the potential of the new cultural institution as a strategic planning tool would be careless.

Planning Aspects of Cultural Policies

Seoul is at the centre of a pattern of urbanisation that has facilitated an excessive concentration of people, as well as of economic and cultural activities. This imbalance has presented economic challenges such as excessive land prices, which have led for example to housing unaffordability and a lack of social overhead investments. Even if these issues are not directly felt by all of us, they impede universal economic growth and therefore influence our quality of life in the long run. This problem will not simply go away or automatically solve itself. Market mechanisms tend to reinforce agglomeration processes and will only exacerbate the problem. That is why there is a need for government intervention and active decentralisation efforts.

These interventions may take the form of improvements to cultural facilities and the creation of employment opportunities in secondary cities but could also involve softer policies related to image management and livability. Cultural institutions can be used as pertinent instruments for the promotion of decentralisation because they address both goals: the need for physical improvements from an urban planning perspective and the necessity to improve the public perception of cities from an image management perspective.

To enhance the competitive edge of cities, culture is often used as a driver for economic growth. The example of Bilbao in Spain illustrates a culture-led urban transition rather well; the so-called urban renaissance experienced by Bilbao is only in part the result of the construction of Frank Gehry’s museum. The Guggenheim Bilbao Museum is a strategic asset and landmark that has promoted a new image and identity of the city. In the language of marketing, it is without a doubt internationally recognisable. However, the now widely acknowledged ʻBilbao Effectʼ is the result of a large-scale implementation of a comprehensive and integrated strategy that is, in the words of Frank Moulaert and Arantxa Rodriguez compiled of ‘a proactive approach to spatial planning, the adoption of strategic planning and a large scale urban project and infrastructure’, not of one building alone. In fact, a large-scale urban regeneration strategy was the driving force behind this metropolitan planning scheme underlining the importance of addressingculture as a resource and not as a commodity.

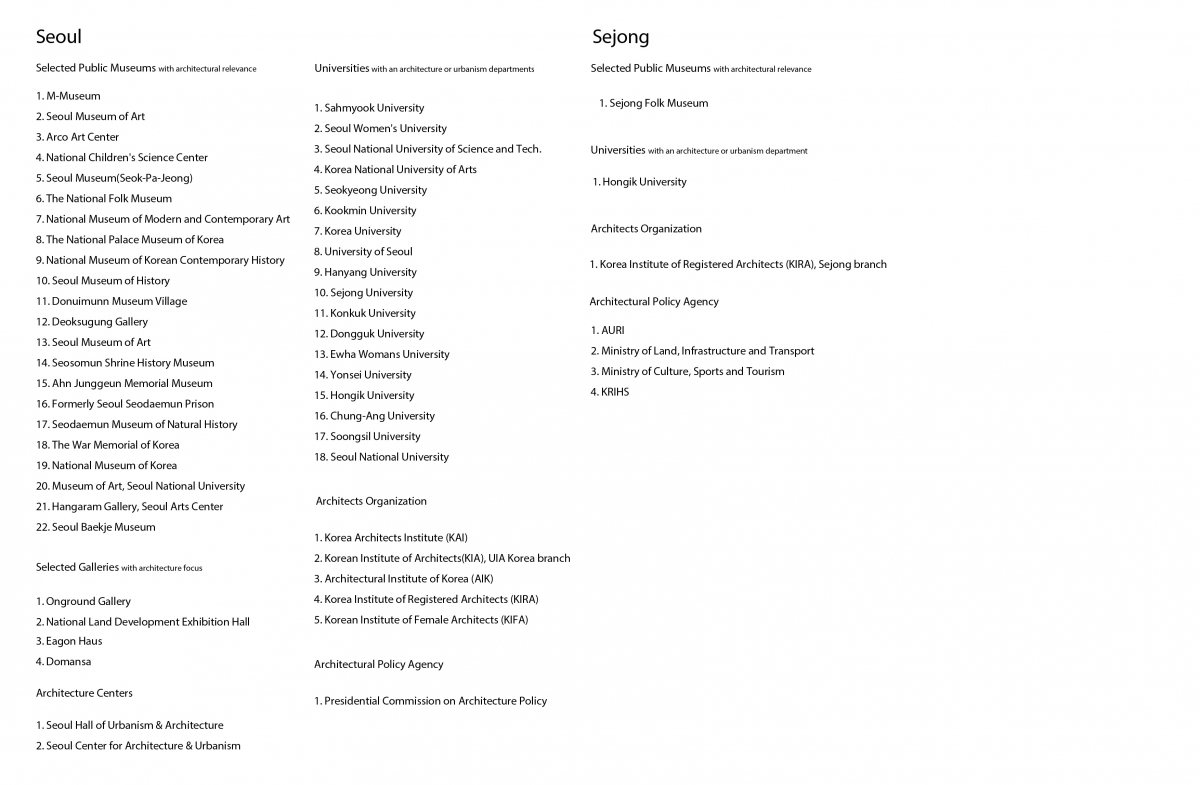

In addition, as a response to the voices claiming that the KMUA is a loss for the architecture industry in Seoul, we want to briefly present an overview of selected urban and architectural works related to cultural infrastructure in Seoul and Sejong. It is obvious that Seoul far outnumbers Sejong in terms of cultural and educational institutions. Seoul already has architecture and urbanism related museums, a wide range of universities with architecture or urbanism departments, an international architecture and urbanism biennale, a network of public architects and village architects, plus several national architecture institutions also located here. The cultural ecosystem of Sejong is small in comparison. We ‒ located in Seoul ourselves ‒ understand how one might assume that greater cultural density is superior, but wonder what the KMUA could add to the architectural infrastructure in Seoul if we set our personal preferences aside. Would anything noticeably improve in Seoul where we already have a well-established architectural infrastructure?

Comparison between select architectural and urban institutions in Seoul and Sejong

Cultural Policies and Creative Industries

The architecture and urbanism sector is an interesting cultural policy area from an urban planning perspective because it is one of the sub-categories of the cultural economy associated with the traditional, as well as the modern aspect of the cultural industry. The conventions that dictate cultural policy are concerned with the preservation of cultural heritage as conveyor of cultural identity, which does not produce any direct profits other than from that of tourism. The modern conception of the cultural industry refers to the creative economy ‒ in our case an active, lively architecture and urbanism ecosystem ‒ as a profit driven economic activity predominantly carried out by highly educated, creative knowledge workers.

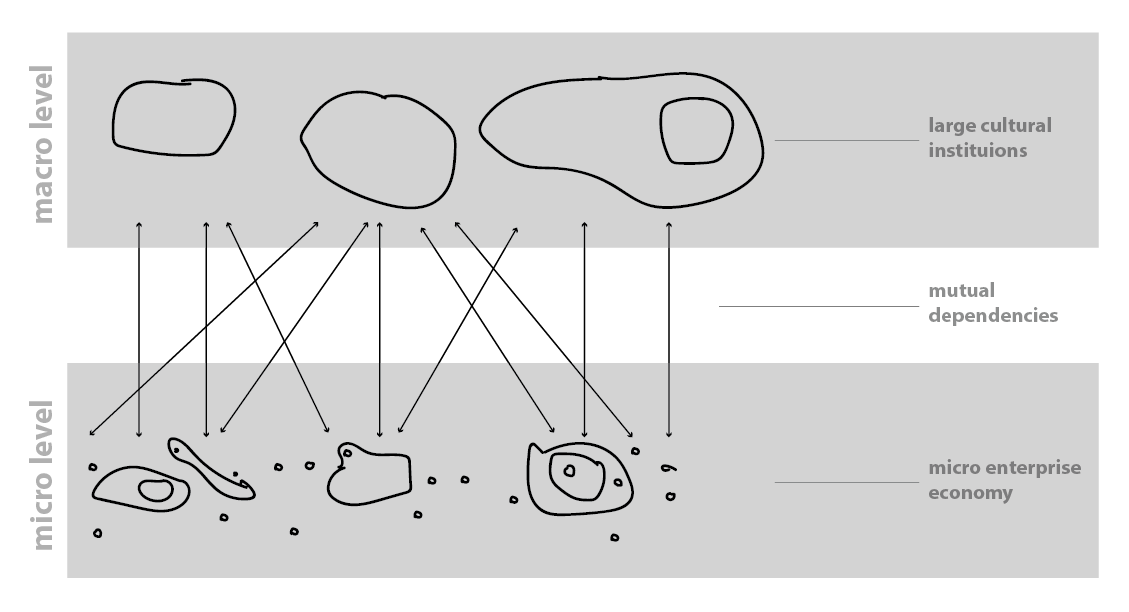

The architecture and urbanism industry can therefore diversify the local economy in a mono-functional city like Sejong by attracting the culture and heritage oriented tourism, while also nurturing a new, knowledge-based architecture and urbanism related, creative economy, promoting exchange between exhibitions and education, and functioning through the museum and in the innovation and experimentation of local practices. The KMUA could work as an institutional ‘anchor’ at the macro level providing exposure, employment and funding opportunities for a predominantly small-scale architecture and urbanism related production. It does not stop here. Following the ideas of David Hesmondhalgh and Andy Pratt, there is a ‘depth’ to the creative industries which acknowledges not only the producers, participants and consumers of cultural production, but also the related industries involved in the production. Aside from architectural and urban design professionals, this also involves curators, architecture critics, architectural photographers, graphic designers, urban geographers, and so on, which are part of the architectural micro-enterprise economy that relies on connections to larger institutions for their economic survival.

Young or small studio architects ‒ often highly skilled and bearing high architectural ambitions ‒ frequently depend on part-time employment at cultural institutions or universities, or the incidental funding for

innovative experiments that these institutions can provide. The Netherlands have shown how a supportive institutional framework can nurture an internationally competitive architectural and urban design scene. Strategically drawing upon the construction of the KMUA to address the problems of an unbalanced urban development is smart. Yet, it is a strategy that is not without risk.

Cultural institutions and the micro-enterprise economy

Threats

The threat that emerges with this strategy is that the unprofessional, superficial implementation of the KMUA might backfire, because Sejong is not the easiest location in which to employ this kind of approach. Strategic urban developments within the cultural industries have in most cases been carried out in post-industrial European cities (London, GB; Essen, DE; Amsterdam, NL; Bilbao, ES; etc.) where idle, rudimentary buildings of the industrial period have become an asset, either as spaces for work and experimentation, or as exhibition spaces themselves. Jane Jacobs for example insisted that there is a need for aged buildings to diversify the rental market. Creative entrepreneurs ‒ especially in the economically fragile early years of independent work ‒ generally want to keep their overheads low and tend to benefit from the low rents typical of old, outdated buildings.

Sejong however, is a newly constructed administrative city consisting almost exclusively of new, modern apartment buildings. The mono-typological organisation and the absence of period buildings does not provide this diverse building stock with idle spaces that are able to welcome a new, self-organising architecture and urban related micro-enterprise economy. Likewise, it is the absence of additional macro-level institutions, such as universities providing employment or international events, ensuring exposure. If the ambition is to maximise the impact of the new museum and to nurture a new, highly skilled knowledge industry with its implementation, then there is a need to immerse the KMUA into a larger network of architecture and urban context related policies and institutions. There is also a need to address unanswered questions regarding the provision of informal, part-time, or temporary employment, the provision of affordable workspaces and spaces for experimentation, and ideally a funding mechanism for talent development. We understand that these ambitions have, in vague terms, been formulated in policy documents by Architecture & Urban Research Institute and the Multifunctional Administrative City Construction Agency prior to the announcement of the competition.

However, these documents are outdated and have been drafted by a different administration. That is why we want to emphasise the ways in which these deficiencies must be addressed by a carefully curated and implemented architecture policy. If this does not take place, the KMUA might not be able to succeed in diversifying the local economy, improving the livability and the public perception of Sejong. In such circumstances, the project will fall short of its planning goals of counterbalancing regional inequalities, and in such a case the KMUA might become the misplaced ‘white elephant’ in Korea. (written by Klaas Kresse, Marta Ramalho Kresse Bastos)

References

1. Hesmondhalgh, D., & Pratt, A. (2005). 'Cultural Industries and Cultural Policy'. International Journal of Cultural Policy, vol.11(1), 13. doi:0.1080/10286630500067598

2. AURI. (2009). 행정중심복합도시 도시건축박물관 건립계획 수립연구 ('A Study on Establishment Planning for Urban Architecture Museum in Multifunctional Administrative City'). On, Young-Tae, 621.

3. Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage.

4. Kresse, K. (2016). 'Dutch Architecture Policy and Institutional Infrastructure since the 1990's'. Architectural research, 18(2), 49-58. doi:10.5659/AIKAR.2016.18.2.49

5. Miles, S., & Paddison, R. (2005). 'Introduction: The rise and rise of culture-led urban regeneration'. In: Sage Publications Sage UK: London, England.

6. Multifunctional Administrative City Construction Agency. (2012). 국립박물관 건립 기본계획 수립 연구 ('Study on the establishment of the basic plan for the construction of the National Museum'). Kang, Cheol-hee, 116.

7. National Agency for Administrative City Construction. (2020). International Design Competition for Korean Museum of Urbanism and Architecture. 1, 21.

8. Rodriguez, A., & Martinez, E. (2003). 'Restructuring Cities: Miracles and Mirages in Urban Revitalization in Bilbao'. The Globalized City: Economic Restructuring and Social Polarization in European Cities, 181-207.