Giovanna Borasi (chief curator, CCA) × Park Semi

Park Semi (Park): The Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) was founded in 1979 by Phillis Lambert, and it has established itself as a new type of cultural organisation, committed to promoting architectural discourse through exhibitions, publications, public programmes, collection of works, research projects, and curatorial programmes over the past 40 years. Could you explain in detail the identity and purpose pursued by CCA?

Giovanna Borasi (Borasi): The CCA was conceived in line with the fundamental premise that architecture is a public concern, and established to stimulate individuals, to increase public awareness of the role of architecture in society, to contribute to the architectural discourse, and to promote research in the field. Since 1979, it has adopted a curious, imaginative and polemic perspective intended to benefit society by offering tools that will explore the role of architecture and probe the larger questions affecting society.

Let me explain how we work and what drives us: the CCA has operated since its beginnings via an institutional framework that demands and underwrites curiosity, both our own, and from our public. Curiosity doesn’t solve problems; it poses untimely questions, charts new lines of inquiry. How can we – from our perspective within architecture, from our outpost in Montreal – address the most pressing questions in contemporary culture and society? How do we proceed in these explorations? How do we anticipate what will be important, rather than just reacting to current conditions? In this way, curiosity could also be a way of taking responsibility, of taking a risk.

The framework we work within at the CCA is articulated as a series of questions we ask ourselves. What about the environment? Can we expect technology to solve our problems? What about health? What happens after ‘progress’ fails, or, sometimes worse, succeeds? How do we experience the built environment in ways beyond the visual? What tools do individuals have to influence the forms and power dynamics of the city? And, most of all, what are the assumptions that shape how architects work? Can we imagine other ways of being an architect? We set an agenda that would point to something latent, off, tense, or unacknowledged, in order to create a platform for the discussions we would like to see take place.

The CCA now turns its collective attention to investigating these questions, through the prism of all the tools we have developed over the past 40 years. Before opening to the public, the CCA gave itself plenty of time¬ – ten years – to learn to do what it wanted to do. Exhibitions in the temporary office’s reception area were practice runs for processing newly acquired archives, conserving objects, writing labels, and finding audiences. There have been conferences, lectures, publications, and invited researchers.

With the arrival of Mirko Zardini as Director in 2005, the CCA started to push more and more for aspects that would infect and inflect one another, to become greater than their sum. Today, the collection is put to use in research: research drives its exhibitions and books, exhibitions reach a wider audience in public programmes and online, public programmes create a conversation that feeds back into what we research, exhibitions and publications reshape the way we understand architecture and what it can do, and therefore what we collect and what we research.

Later this year, we will publish a seminal book reflecting on years of thematic investigations and attempts made to rethink the institution: The Museum Is Not Enough (co-published with Sternberg Press) will present the curatorial activity at the CCA today organised around a set of questions, and creates a conversation with other people who are working on and thinking about similar issues.

Park: I would like to hear about what position the CCA is taking within the context of urban architecture museums and similar organisations in Canada, and how the CCA engages with and relates to them.

Borasi: We constantly ask ourselves about the positions we take and defend in the international landscape of architecture museums and research centres. We are the Canadian Centre for Architecture, not of Architecture: the CCA was conceived with an international scope, representing the evolution of a larger debate around architecture and the built environment, so it does not follow national, historical traditional narratives. We appreciate the diversity of cultural institutions in Montréal and in Canada, and very often collaborate with others through lending our collection holdings, through occasions and events, or hosting them at the CCA with their events when related to our lines of investigations. This could be, for example, a symposium on digital architecture, a documentary film festival, or a series of workshops on housing and urban planning, as well as concerts, performances or screenings.

Park: CCA is a private museum. How does it maintain its budget?

Borasi: Today, the CCA, as an independent institution, receives 40% of its financial resources from its endowment, 50% from private support, foundations, and earned revenue, and 10% from private grants. This implies the need for constant initiatives to raise funds, as an institution wide exercise, driven by its content and mission. In recent years we have received important national and international grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Graham Foundation and the Canada Council for the Arts, all of which recognise the value and importance of the CCA in the wider cultural landscape. Such support has been fundamental in enabling us to strengthen our research programmes, our public programmes addressing our community, and to implement aspects of our digital strategy aimed at reinforcing our presence and influence, both locally and internationally.

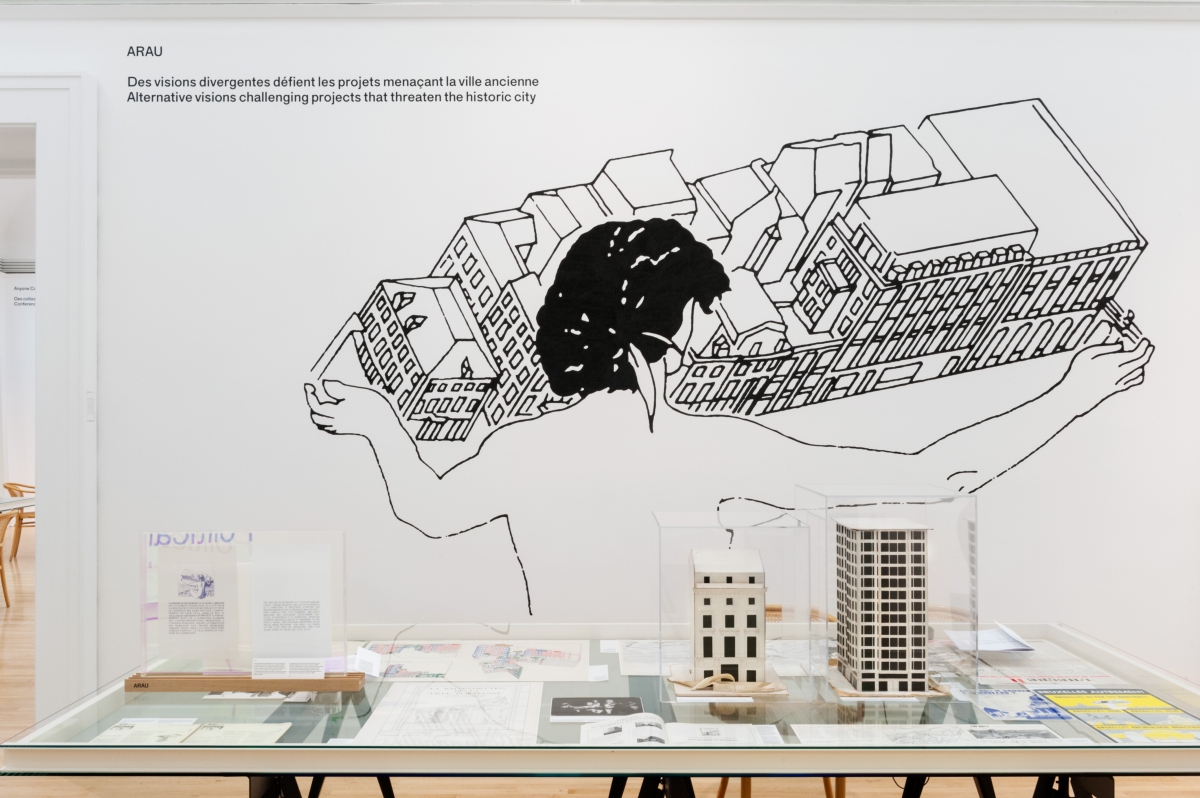

Installation view of ‘The Other Architect’ (2015)

Park: Archives and collections are the traditional practices of a museum, but the quantity and quality of the resources are a crucial basis in its exhibitions, education, and research. What is the meaning of archives and collections for an urban∙architectural museum, as opposed to an art museum? CCA documents and stores about 250,000 publications, including architectural papers and periodicals, drawings and prints dating from the 15th century to the present, more than 65,000 photographs, and 200 projects related to architects and artists in the 20th and 21st centuries. Could you tell us more about your criteria for collecting archives and your methods for storing and managing the resources at CCA?

Borasi: From its beginning, the CCA clearly assumed an international mandate for architecture, building its unique collection with archives from many different countries. Today the CCA holds one of the world’s foremost international research collections of archives, publications, photography, prints and drawings on architecture, including the international archives of Álvaro Siza, Peter Eisenman, Arthur Erickson, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, John Hejduk, Gordon Matta-Clark, Cedric Price, Aldo Rossi, James Stirling, as well as Abalos & Herreros, Foreign Office Architects, and the archives of historians and critics such as Kenneth Frampton, among others.

The CCA collection reflects the diverse ways in which architecture has been imagined, conceived, observed, and transformed over the past six centuries. It is a collection that stimulates the study of ideas, the evolution of tendencies and movements, diversifies theoretical and practical approaches, and new architectural and urban forms.

In the past decade, the CCA has been very selective about acquiring new holdings, in order to grow the collection consistently, but also about how it opens up new possible lines of inquiries. Along with this thematic research, the CCA continues to accept the donations of complete archives or sets of relevant projects by architects whose work will contribute to expand the discourse on architecture in the 20th and 21st centuries (already the strongest focus of the holdings), along with seeking donations from a younger generation that will introduce new and more experimental projects to the collection.

This final component is related to our exhibition and publication series ‘Manifesto’, where two active practitioners were asked to hold a conversation on a selected topic and display their work and approach. While CCA thematic research, exhibitions, and publications feed from and give visibility to the collection by contextualizing it among content originating elsewhere, the ‘Out of the Box’ programme enables the CCA to specifically and actively expose archival material to research activities and to discovery as the archive is being organised, processed, and reassessed. In 2019, for example, this approach will be applied to the archive of Gordon Matta-Clark, with three curators invited to select objects from the archive and develop an argument around them that they will present in a series of exhibitions and a joint publication.

The CCA’s relatively recent exploration of early digital architecture is due in great part to the acquisition of 25 born-digital projects and/or archives from the mid-1980s to the early 2000s that truly capture an experimental time in history in which digital tools were shaping both the theory and practice of how architecture could be conceived and produced. These archives present truly unique opportunities to explore digital architecture across all CCA areas of activity - for example, a series of three exhibitions (CCA and Yale University, 2013–16), two print publications (2013, 2017), 25 digital publications, and a series of oral histories all on the role of the digital in architecture as part of the CCA’s multi-disciplinary Archaeology of the Digital project.

Park: Other than archiving, CCA has organised more than 200 exhibitions, published more than 100 books, hosted 500 lectures and conferences, and supported and offered training to more than 1500 researchers. While it carries out functions such as archiving, exhibiting, publishing, educating, researching and holding events, it also embraces architects, scholars, and the public. What efforts do you put in to keep each function at such a high-standard and so well-balanced? Also, how do the different functions that CCA operates complement and synergise each other?

Borasi: Operating principally as a research institution, we are concerned not only with building new knowledge but also making that knowledge useful and productive for others. The CCA is a centre, not a museum. It’s a place that collects - objects and archives, yes, but especially figuratively, as in a centre of gravity. It pulls people, ideas, and things to Montreal that may not otherwise visit here. At the same time, we try to make ourselves available more broadly, through our website and through projects like CCA c/o, a series of temporary initiatives that are anchored to locations around the world and define new thematic explorations through encounters with these different contexts. We started in Lisbon, continued in Tokyo and will soon launch the third iteration of the programme in Buenos Aires. We are counting on the fact that there are others out there who are asking themselves the same questions as we are.

Another way we’re negotiating this right now is through a strategic project we call Find and Tell, where we invite experts - not only scholars, but architects and other people with intelligent viewpoints - to revisit the collection from a contemporary perspective and to stake a claim on the selection and interpretation of a body of material from our collection, which is then made accessible online. This approach is part of a bigger shift. Although we are always improving and questioning how we use our first building in Montreal, we don’t want to expand it. We’ve been investing in what we’ve called our second building: our website and this other presence, CCA elsewhere. Now that we have the second building, we have to occupy it. We ask ourselves: how do we reactivate the collection from a contemporary perspective, and then share these insights? If we do something and it doesn’t live in the second building, what is the point? If digitisation, for example, is not an automatic action, or a purely technological problem, how do we move forward? If the archive is a tool, what is the thing we are making with that tool?

We’re not sure what the result will be, or what exactly we’re making. Of course, the risk of curiosity is of being misunderstood. We have to take a position - to dive into something that seems premature in order to arrive at something else that resonates with even more urgency. As it has developed, as it enters its fortieth year, the CCA is an institution that protects our ability to be curious.

Park: Without confining things to the field of architecture, CCA’s recent exhibition titles include ‘Where’s Class?’, ‘It’s All Happening So Fast: A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment’, ‘Archaeology of the Digital: Media and Machines’, covering a wide range of subjects related to economy, society, and environment. To what extent do you think architectural exhibitions cover a broad range of issues? Also, how are these exhibitions, which cover topics that are an extension of architecture, contributing to architectural discourse?

Borasi: Adding to what I mentioned earlier, to us at the CCA exhibitions, publications, events, and acquisitions are never objectives in themselves – they are tools to achieve the institution’s goals, and to investigate and explore the ‘grey zones’ in contemporary culture, contemporary society, and contemporary architecture. This critically exposes contradictions and defines a new agenda for architectural practice and scholarship.

At CCA we always see architecture as a way of thinking about the present, the society in which we’re living and working. But if we want to read the world through architecture, we have to decide where exactly to focus our attention. Architecture carries intentions: it aims at a result, calling a reality into being. For that reason, it can help us come to specific terms with failures of ‘progress’ – a recognition that the world is not getting better, that all our grand ideas have other consequences. These failures are becoming more and more apparent.

So we shape curatorial practice by bringing attention to key topics along thematic lines that have particular relevance and urgency in contemporary society. This curatorial strategy differs to more traditional approaches of organising projects by medium, geography, or era. Instead, we look at the built and unbuilt world through the lens of architecture’s engagement with digital technology, the role of photography in architecture, the environment, architecture’s relationship with history, the topic of education in a new digital world, and happiness and well-being. Our activities place architecture, the city, landscape, and broader environment in a broader cultural, social, and political context, showing how they are interwoven with one another, what they are responsible for, and how they can contribute to defining problems and proposing alternative solutions.

We also like to explore new ways of driving curatorial practice across research, exhibitions, publications, related lines of acquisition for the CCA Collection, and critical debates through public programmes. This means rethinking the discipline and the boundaries of curatorial practice by questioning and re-examining the role of architecture and architects in contemporary society. We do not have the answers, but we offer a space and context in which to reframe the questions.

Park: CCA is also focusing on raising public awareness of architecture’s role in contemporary society. How do you feel and experience changes in the relations between museums and the public? What role should an urban∙architecture museum play, in order for architecture, as a professional field, to communicate with the public?

Borasi: We are committed to building a sense of community and strengthening connections with the public by bringing the work and ideas of architects, students, and scholars to more general audiences as individual and collective agents of change in the conversations about architecture as a global public concern.

The formats of these conversations are far more than programmatic frameworks - but rather wild, wonderful, and ever-changing experiments in the ways we can investigate architecture’s role in the world, potentially even creating conditions that allow for new forms of architecture to develop. Ultimately, our objective is to introduce and amplify voices other than our own in relation to expanding the disciplinary boundaries, professional practices, and relevance of architecture in contemporary society today.

And through new and experimental formats of public engagement, we are taking full advantage of the digital realm, shifting from traditional ideas about education to the idea of conversation with younger and more diverse audiences, including students, young professionals, and a socially and politically engaged public.

Sometimes, the perspectives we invite are complementary; other times, they are contradictory - that’s part of what makes it interesting. Talks, lectures, and seminars serve to multiply the number of viewpoints we can make sense of and explore together, while our workshops and tours introduce what we are thinking and doing in order to initiate discussions and share insights.

There is always a digital component to our conversation with the public - whether it has an online presence, produces online content, or itself emerges from the second building. All of these digital expressions are key to our efforts to be as accessible as possible to both specialised and non-specialised publics as we strive to raise public awareness of pressing social issues and the challenges that society is facing vis-à-vis the built environment - including climate change, migration, and social injustice.

Park: The activities of CCA are becoming an exemplar to other museums dealing with urban∙architectural contents and similar institutions, while challenging them as well. However, not every urban∙architectural museum can become CCA. Last March, you were invited by the Seoul Metropolitan Government and visited the Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture to attend the International Conference that was held at the Opening Ceremony of the Hall. We would like to hear briefly about the ideas shared at that time. Could you add your thoughts, expectations and advice for the direction that the Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture should take?

Borasi: I really liked how the Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture, as a building, is very inviting and open to the public. From the architecture itself I would have wished for more fluidity between the different spaces, which appeared to me a bit too separate from each other.

I think that it is fundamental that a culture and a city like Seoul – with rapid urbanisation and economic growth – offers open spaces to their citizens like this one. Equally important is the programing of such spaces: It should address issues that are of concern to the population, and explain the arguments and tools, that architecture has to offer today. Like, what is a master plan, why and how we do a master plan. It has to explain the ideas behind urbanism and architecture, and the tools that the city has in place, and how, as a citizen you engage with that. But I think it is also important that such an institution offers a programme that can connect it to an international network of similar institutions, and proposes sets of topics for discussion that are relevant to a larger, international audience. And I wish the Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture would establish a long-term programme. I would be very curious to see what it includes.