SPACE November 2023 (No. 672)

10 years have passed since the design competition system was overhauled as a consequence of the Act On The Promotion Of Building Service Industry. As multiple adjustments and corrections have been made over time to the operation of design competitions, the system has given birth to numerous selections that populate our surroundings today. If these winning designs, which were born out of the creative struggles of individual designers in their respective times and places under the aegis of ‘good public architecture’, were to be assembled in a single space, what would stand out? SPACE have selected 30 distinguished examples of public architecture that have been recognised by the architectural scene over the past 10 years. We compared images of the winning designs and their results, and interviewed the architects. Our selection criteria was primarily based on being honoured with selection, but we also wanted to offer as diverse an outlook as possible according to type and year of competition, ordering institution, and use or function, to offer a wide spectrum of examples. When it came to public residences, we decided not to feature them in this article as they are a unique breed in terms of scale and programme. By reviewing all stages, from planning, examination, selection, and the post-construction phases, and after hearing from those responsible for them about the obstacles that they faced on their journey towards good public architecture, we hope that the testimonies of these people who witnessed the various aspects of the design competition system will give us a sense of continued direction as to where we should be heading in the next 10 years.

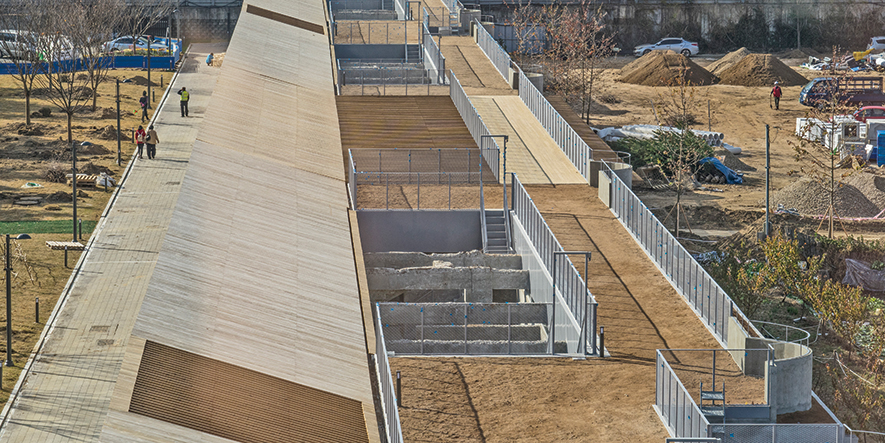

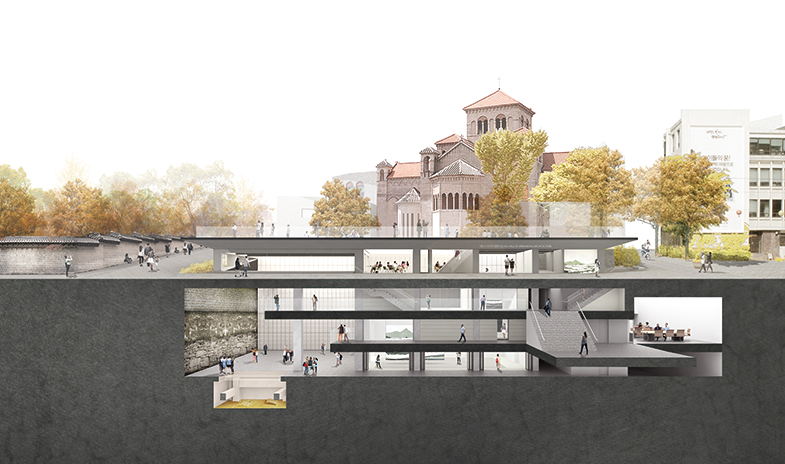

©VOID Architects

©Kim Jaeyoon

Q1: From the design competition to construction, what was the main task when it came to the completion of your project? In which areas do you think your project did well, and what made this possible?

A1: Our project was reviewed positively for reusing the original town composition which had drawn its residents together as a welcoming community as part of a common living room for the locals. While it is unfortunate that the project’s scale resembling the original town composition had to be set aside due to construction costs, the revitalised alleyway and yard in the building continue to be the main point encouraging spontaneous meetings and events. While originally the senior centre was to be dismantled and the town was to be set in a central park for Yeongju-si, Lee Sojin (principal, Leeon Architects) who participated in the town masterplan suggested a readjustment to the district-level plan to keep the town largely intact as we find it today. The Yeongju City – which was the first local government to institute the Public Architect system in 2009 – and its public officials involved in urban architecture have actively aided architect-led spatial constructions via administrative support. This mutually cooperative system between urban architecture related institutions and private professionals has since continued despite changes to the leadership in local government.

Q2: What suggestions would you make to improve the way design competitions are conducted in Korea?

A2: It is not appropriate to hold an elected designer responsible for meeting the final construction budget by asking him or her to propose the area limits and estimated construction costs at the stage of a design proposal. This is because things like unique site conditions and inflation rates are not reflected in construction costs and different calculation standards are employed per project. Design costs fluctuate according to construction costs. This often leads to deviations from the original plan in terms of space and physical features. Much energy would be saved when competing for budgets if some margin for modification in the area size in consideration of the new programme to be introduced and appropriate construction costs in line with the interests of the design proposal could be granted.

2013 general design competition (for rising architects)

Architect

VOID Architects (Zhang Kiuck, Lee Kusang)

Location

642-10, Hucheon3-dong, Yeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do

Programme

welfare facility for senior citizens

Gross floor area

2,335.28m²

Design cost

budget – 206 million KRW / actual cost – 178 million KRW

Construction cost

budget – 5 billion KRW / actual cost – 4.7 billion KRW

Competition year

Sep. 2013

Completion year

Jan. 2017

Client

Yeongju City

Prize

Korean Architecture Award (2017)

VOID Architects (Zhang Kiuck, Lee Kusang)

642-10, Hucheon3-dong, Yeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-d

welfare facility for senior citizens

2,335.28m²

budget – 5 billion KRW / actual cost –

Yeongju City

Jan. 2017

budget – 206 million KRW / actual cost ̵

Sep. 2013