SPACE January 2023 (No. 662)

Art and Architecture: Dialogue for Collaboration and Crossover

Dialogue_ Kim Jang Un director, Art Sonje Center × Choon Choi professor, Seoul National University × Kim Jeoungeun

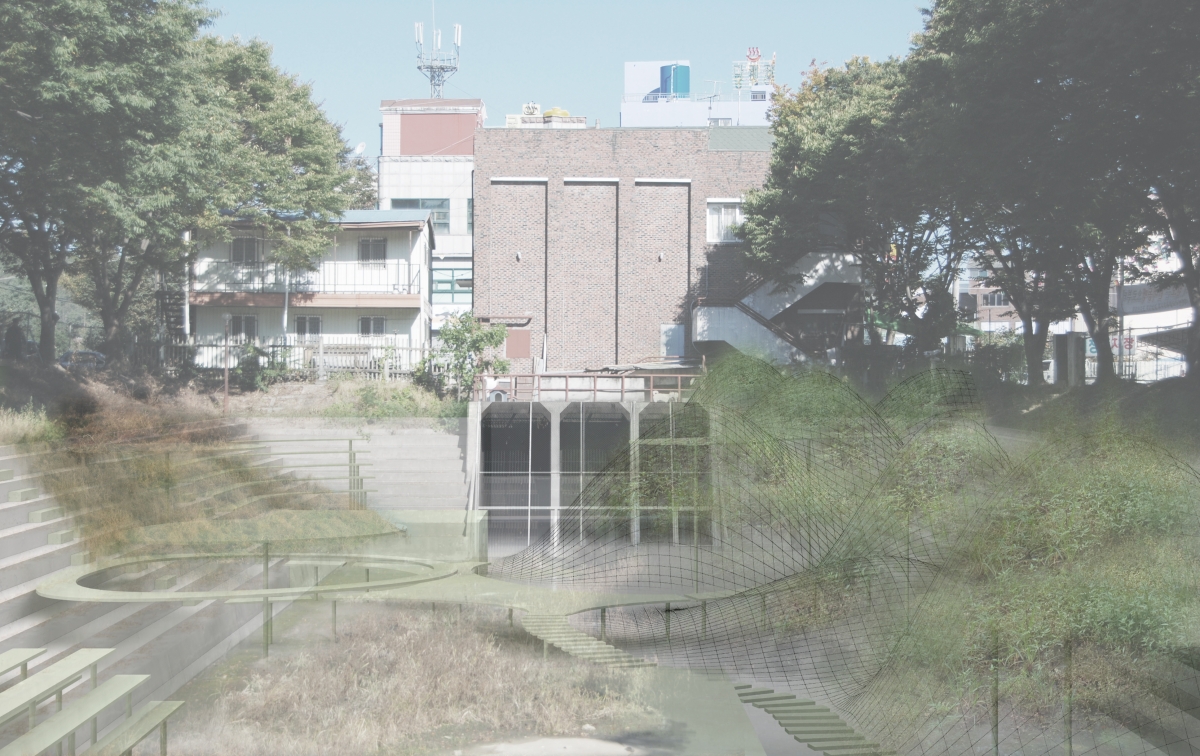

Exterior view of Gumseong Drainage Facility and asteroid G, cubic modular (left) and bridge (middle)

asteroid G

Kim Jeongeun: There is a growing trend in the architectural field for restoration or remodeling projects or even newly built projects, that are built in a style that has existed for a quite long time. The public sector has been trying to transform old buildings and infrastructure into cultural spaces over many years. The Noryangjin Sewage Walk and Magok Cultural Center project, recently showcased by Choon Choi, are examples of public infrastructure transformation, and can be said to be part of this trend. If you look at the full range of his work, we find an architect responding flexibly across various collaborative networks. Here, I want to talk about Choon Choi’s early work asteroid G which is also in the field of public art. It would be nice to point out what kind of ideas prompted its creation, as well as how the mastermind behind the project dealt with a artist, architect and a structural engineer.

Kim Jang Un: Asteroid G is the winning project in the Arts Council Korea’s public art project ‘ARKO Urban Park Artro’ competition. The main purpose of the project was to produce a result with collaborators, being centered on an artist. It may be thought that the focus would be primarily on the artist, but there was a desire to complete the work collaboratively, not on the artist’s own terms. As a curator, I decided to take on asteroid G with the mindset of a challenger throughout the process, from the artist’s idea to realisation by working with relevant experts to enrich the idea and bring it to life. Led by artist Kim Sora, our team submitted an interesting proposal to the Gumseong Drainage Facility in Gongju and was selected for the competition.

Kim Jeoungeun: I heard that you went through six phases of revision. How did the project go?

Kim Jang Un: The winning proposal was to insert a structure resembling part of the topography of Gongju into the drain facility in the form of a contour. However, in the

process of realising this design aim, Gongju City presented conditions that could not embody the original design. Drainage facilities are legally classified as disaster facilities, so the maximum water storage capacity was stipulated, but the city intervened and said that the water storage capacity could not be changed. In order to maintain some vestige of the original plan, we had to prove that there was no risk to disaster prevention measures even if the water storage capacity was reduced by the volume of the inserted structure. The whole team panicked when they had to scrap the original plan and start from scratch. Since being selected, I’ve had to come up with a new plan, no matter how I’ve been researching and I still can’t come up with an answer. Then Kim Sora suddenly proposed to make stones, and the project was rebooted. Kim Sora found a stone while wandering around the site and nearby mountains in search of a stone that could be used as a sculpture. When it was reported to the city that we wanted to make a sculpture in the shape of this stone, they were shocked and kept their face straight. Kim Sora, who intuitively felt that it was difficult to proceed with the project, said she would abandon her idea and ‘sit back and see how the project progressed from then on.’ (laugh)

Choon Choi: I still keep the stone that Kim Sora picked up. (laugh) I was wondering why it had something to do with making stones?

Kim Jang Un: When I asked Kim Sora, she said there was no real reason behind her desire to make a stone sculpture. Looking back, it was a time when the big names in the art scene were using stones as objects of contemplation. They talked to stones and used them as their materials. Our team also studied while looking for examples made by Spanish architect Antón García-Abril (co-principal, Ensamble Studio) with the idea of making real stones. However the process of executing them was not easy.

Kim Jeoungeun: In addition to the cubic modular – a structure originating from stone – asteroid G also featured the installation of an iron bridge. Where did it come from?

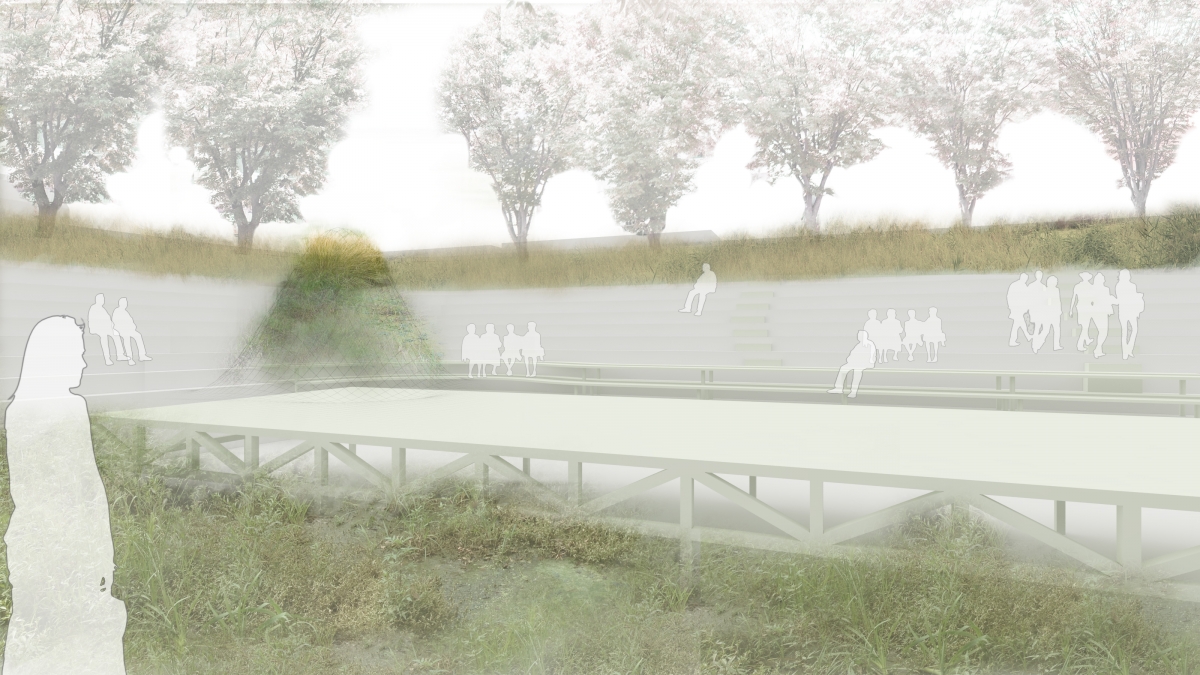

Bridge, asteroid G

Kim Jang Un: What our team was more sympathetic to at the time was that the land was an abandoned place. The entire site was fenced off and people had to make detours. We reached a consensus to tear down this fence and open up the site. After considering how to guide people approaching the land, we proposed a walking path through the drainage field. Coincidentally, Geumgang Iron Bridge, a bridge built during the Japanese colonial period, still remains in Gongju, so it is used as a motif. When we showed a simple structure design, modeled after the arched structure of a railroad bridge, the city expressed disappointment, as they expected a more grandiose sculpture. Later, the city officials said they were satisfied with the walkway, but they probably thought they could do something about it after the project! (laugh) It somehow happened to be a bridge-building project, which was organised to open up this isolated, enclosed space and open up terrain for people to use.

Choon Choi: At that time, there were dog meat restaurants and trucks selling dogs located around the fence. I felt that it would be preferable if that aspect of the area just disappeared through this project. The bridge itself is designed to play a structural role and is efficient. Compared with local facilities that imitate the shape of local speciality products such as Gulbi Bridge (fish shaped bridge) in Yeonggwang-gun, Jeollanam-do, I am proud to have built a building without redundant structures.

Kim Jang Un: I happened to visit it a few years after it opened and it turned out to be a purposeful bridge. It became a shortcut across a road that was blocked by the fence. When I visited again about two years later, I witnessed that it had become a bridge of love, as it has become a place to hang love padlocks. This was of course unintended, but at night, it is beautiful—brightly lit and quite antique.

Kim Jeoungeun: How did you manage the bridge construction? Did it go as planned?

Kim Jang Un: Gongju City said it would build it on its own, so it was forced to accept this. As we declined, we decided not to go any further. We also asked the construction company not to introduce anything other than the design drawings we submitted. At the last minute, the city urged us to do a community art project, so we invited the Part-time Suite and held a full-day outdoor performance at the end of November. The stage was set up on the site and a wonderful performance was held, but no one came! (laugh) It seems that the residents had the will to complete the project without doing a thing from the moment the stone was no longer realised. Like a structure that has stopped being turned into stone, so too the fact that our demands were not accepted. Even if the city asked to put some flower pots and make sculptures on the

bridge, the proposals were all refused. At the end, the city asked us to paint the deck floor of the bridge with orange colour, but we told them to do it after the project. It was a project that by ‘doing nothing’ I was still proud of.

Kim Jeoungeun: I think the slogan ‘I did nothing’ is an expression that runs through this whole project.

Kim Jang Un: Projects in other regions that were selected along with asteroid G also featured community art projects, but our project eliminated this part from the beginning. This is because the collaborative process between the participating artists and experts is important. Instead of focusing on communicating and giving back to local residents on the grounds of public art, it is better to focus on reflecting the artistic achievements of the works. Dongdaemun Design Plaza, designed by Zaha Hadid, is

considered to have destroyed its regional character, but on the other hand, the architect seems to have presented her vision by pursuing her own vision. I think the inspiration and experience that this space opens up is also important. We don’t judge that our approach was wrong, just because the public is not involved in the process of making public art.

Bridge, asteroid G

The Meaning of Collaboration and Attitude

Kim Jeoungeun: What made you invite Choon Choi to be the project architect?

Kim Jang Un: We first met at the 7th Gwangju Biennale (2008). At that time, I was the curator of ‘Position Papers’ exhibition, and Choon Choi was responsible for the spatial design of the entire exhibition. At a meeting to discuss the concept behind the exhibition space, Choon Choi made a presentation with a model. It was very impressive that the architect in charge of the exhibition space did not build his own architecture, but rather grasped the exhibition concept and intervened in its interpretation.

Kim Jeoungeun: What does it mean to intervene in the interpretation?

Kim Jang Un: When an architect comes in as an exhibition space designer, the architect often goes his/her way even when the curator weighs in about the guiding exhibition concept. It is a means of inserting their own symbolic architectural vocabulary throughout the exhibition. However, it is very difficult to interpret the concept of the art director, apply it to architecture, and adjust the architectural language. At that time, even overseas, it was rare for an architect to fully respect the ideas of an art director while also applying their own architectural vocabulary. In Choon Choi’s presentation, comprehending the concept of the exhibition and designing it out with his own vocabulary, was outstanding. At the time, he proposed a concept in which the grids on the walls of the biennale exhibition hall change rhythmically, but the grid was not his signature expression— it was a rhythm he created while reflecting the concept of the work and exhibition. It was nice and surprising that there is an architect like him in Korea. I can read the rhythm when I visit the exhibition space. I figured that Choi is very well equipped to collaborate with other artists.

Kim Jeoungeun: Why did you find it difficult to collaborate with architects?im Jang Un: In my personal experience, the most uncomfortable partners to work with are architects. Architects seem to think that they can do anything by themselves because they have their own thoughts and feelings as well as the ability to express and build. For this reason, the negotiating process with the architect is usually difficult. I’ve met an architect who specified which works fit into the exhibition space he designed.

Kim Jeoungeun: I was expecting this, but It is still surprising that he really means it. (laugh) You seem to know architects well.

Kim Jang Un: When I met Choon Choi later, I told him that he is of a different feather, different species, and he replied that he once studied stage design. So I thought that must have made him more flexible.

Choon Choi: I worked hard during the Biennale, but in the end, it seemed like I didn’t do much. The Gwangju Biennale Foundation saw my work and said it was possible to design an exhibition space without an architect. (laugh)

Kim Jang Un: It’s sad, but I think it reveals a limitation in the Korean art world. It is such an amateur’s way of thinking to claim, ‘I could do it by himself’ without noticing the subtle tensions and rhythms that orchestrate overall spaces. Experts also seem to have misjudged, because uniqueness is not easily noticeable.

Bridge, asteroid G

The Boundary Between Public Art and Public Architecture

Kim Jang Un: I understand that you have participated in projects that require intervention and coordination more than in new construction projects starting from scratch. I heard that architects don’t like this kind of work. Did you find it difficult?

Choon Choi: A similar question was raised in a conversation with Kim Kwangsoo (principal, studio_K_works). Why do you prefer that kind of work and why do you feel more comfortable with it? It’s a place I can rely on and hide myself, so I feel relieved in situations where I don’t have to put myself out there.

Kim Jeoungeun: You also described yourself as a ‘cleaner mind’, and I understood this to mean that you have an attitude of organising things as if you were cleaning rather than taking active actions such as adding or removing something.

Kim Jang Un: I feel that in a project for a public space, the artist’s critical attitude towards restoration is lacking when creating a logic of intervention in any existing historic building or space. Even in remodeling works, it seems that the effort to look good in photographs is repeated. Whether it is an architect or an artist, when trying to change the use of a public space that has already been used, I think it is necessary to redefine the meaning of the space, and then translate it into an architectural or design language to produce an outcome. To do this, there needs to be a new awareness and a series of dialogue, but unfortunately, this process is treated like ‘just work’ (administrative task) and cannot pass through enough time and process. Choon Choi: This doesn’t seem to be a problem that is unique to architects. Isn’t it the case for societies and systems in waiting? I think those who keep experimenting in this environment are contemporary artists.

Kim Jang Un: I can’t say it applies to all, but even artists these days seem to be complacent and adapting to this situation. I am often responsible for deliberation or consultation of public art-related projects, and there are many cases where public art projects in the public domain are combined with facilities or require specific structures. It is interesting that young architects are actively involved in such projects. Many of them succeed to the final round and even win the prize. However, I feel that this situation is a tragedy for both the architecture world and the art world. It seems that the architects are participating in this project because they have no work,

and architects themselves do not seem to find any vision in the project.

Choon Choi: Wouldn’t there be one team or more who really wants to get involved in the competition?

Kim Jang Un: There don’t seem to be many examples. I was once invited to participate in the final evaluation of the results of a public project. I had a chance to look at the entire process of the project by a well- known young architect, and when I compared the initial proposal with the final plan, the core concept proposed at the beginning disappeared and only the plain design remained. The experts there seemed to be generally happy with the final draft, which went through several revisions to reflect the stories of local residents. Somewhat discouraged, I told the winning team directly, ‘In my opinion, the core concept of this project has disappeared, and it seems that the process of coordination and agreement has produced digressive results.’ I also asked if there was any inconvenience to the architects in this compromised process. Then, the answer came back saying that since it was a public art project, they did not insist on any ideas deemed undesirable by the locals. And they said it wasn’t a big deal to abandon the original concept because it was considered a part of their ‘work’. The architect explained that he met the client’s needs, but I had nothing to say. Public art projects are much more varied and flexible than architectural projects, and should be an opportunity for challenge and experimentation, but artists find it difficult to challenge and compete against architects who are treating work as one of their service portfolios. As architects do more public art than artists these days, artist-only public art projects are on the rise.

Kim Jeoungeun: How does the art world perceive the phenomenon of architects actively participating in public art projects?

Kim Jang Un: It seems to be positive because it is easier to invest public funds in a project to improve and make use of an abandoned facility than to build a giant work of public art. Therefore, the targeted participants of the project are also expanding to architects in the field of art, but the process and way of artists and architects are essentially different. Architects are therefore leaps and bounds ahead in their understanding of facilities and structures and their ability to articulate and formaliwe them. At the competition screening, the architect suggested a visible graphic for the colour demo, but I thought that was fictional. Isn’t this an illustration of a perspective that cannot be experienced in reality? In fact, in many cases the concept itself is only possible in graphics and cannot be realised in reality. This is also the reason for forcing the work into the concept image.

Kim Jeoungeun: That’s a fair point. I think it is a message to which the architectural world, which is expanding its professional boundaries, needs to listen.

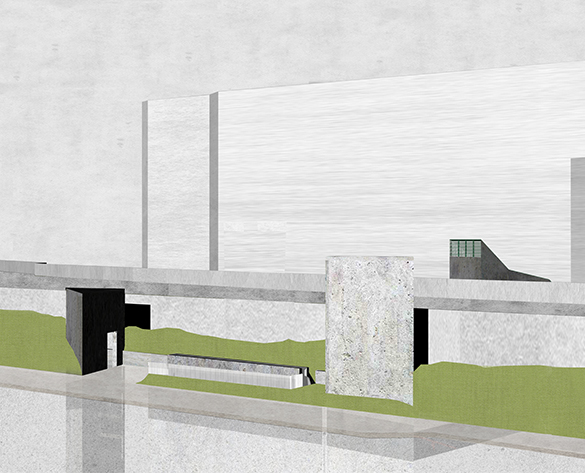

Rendering images of initial proposal, asteroid G

Kim Jang Un: Watching many architects, from mid-career to newcomers, engage in public art projects, I feel like the language of architecture is degrading on a level separate from the discussion of good or bad design. The boom in remodeling or rebuilding projects is explained in the same sense. After more than 10 years of this trend, I see architects becoming spatial managers at some point. For example, let’s suppose you’re meeting with an architect to remodel a market. Instead of coming up with key architectural ideas to change the space and reconstructing and programming the space accordingly, and when you need a space while leaving the building as it is, the architect plays the role of programme manager, such as introducing the right vendor to such questions as ‘which company’s product sells good quality products’, and ‘which kind of activities are in need for the project?’ Building spaces through programming is great, but when I ask architects what their vocabulary or ideas are, they can’t answer. Rather, it is a way of explaining one’s own architecture in terms of trends or circumstances. Many renovation projects are similar, and it seems all works are done by a single designer.

Choon Choi: Among remodeling projects, the actual methodology is similar, and the same thing goes in the situation abroad. Even national characteristics seem to have faded.

Kim Jang Un: It is true that there is a tendency for works to become similar, but the situation in which the architect becomes the editor is a foundational problem. Architects seem to have transformed into editors, the editors who select spaces.

Choon Choi: The tendency for space to focus excessively on programme planning is felt even when taking design classes at architecture colleges. While students spend a lot of time analysing and planning, they forget about the design they need to do. In the critique session, there are many students who do not have their own design.

Kim Jang Un: Is it because the abandoned places are viewed too aesthetically, resulting in a decrease in the involvement of architectural works?

Choon Choi: I thought that there were many cases where people treated it like a sort of fetish, but I think it pointed out the more fundamental part. I think it explains that the depth of the work becomes shallow or results in the loss of direction and purpose.

Kim Jang Un: Isn’t architecture today systematised and modularised because of sustainability and environmental concerns? When I see young architects, when they explain their work, they construct and interpret spaces as if they were placing objects in 3D tools. And when the question was addressed to spaces specifically, somehow they are selling products. Where construction materials and modules are readily identified, the work entails curation and combination in accordance with the client’s preferences. Architectural catalogs that emerged in the United States in the early 20th century seem to have evolved into our times. There is nothing more to add about whether the ‘architect as editor’ is the ideal future state for architects. I may have a modernist outlook, but I doubt whether it really fits with the role of the architect.