SPACE January 2023 (No. 662)

Dialogue with the Past: The Cultural Transformation of Urban Infrastructure

Dialogue_ Kim Kwangsoo principal, studio_K_works × Choon Choi professor, Seoul National University × Kim Jeoungeun

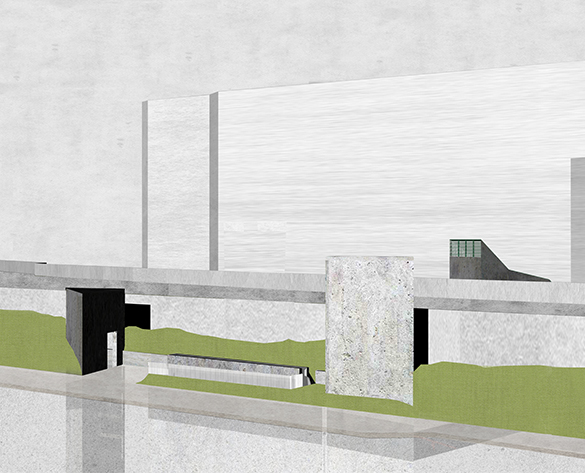

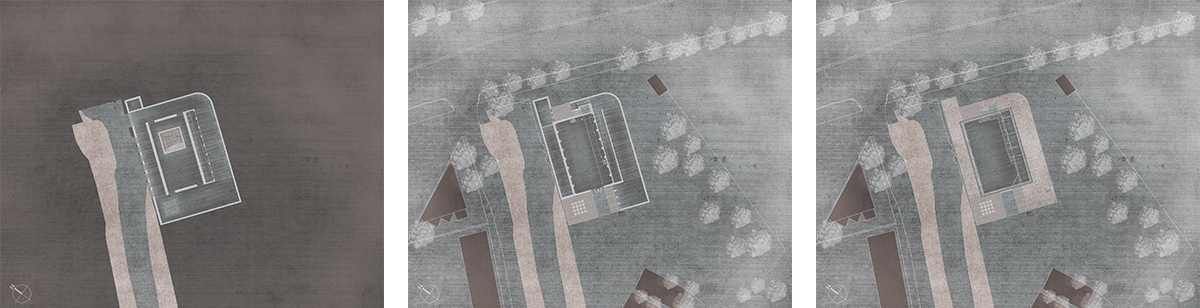

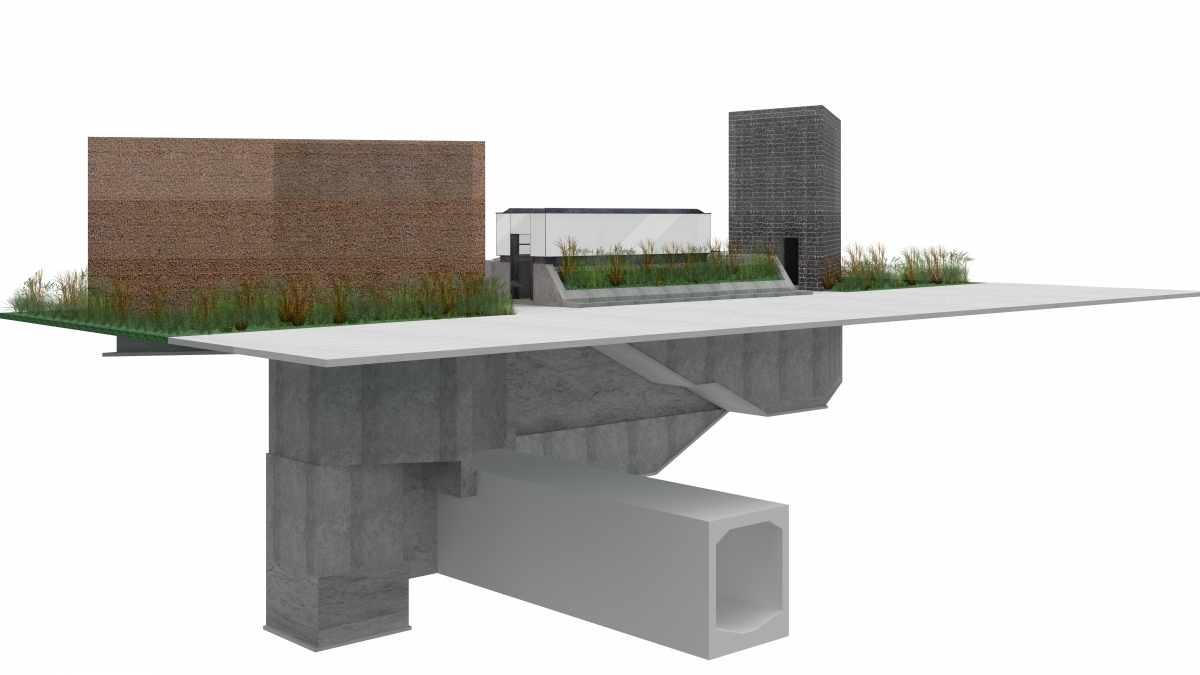

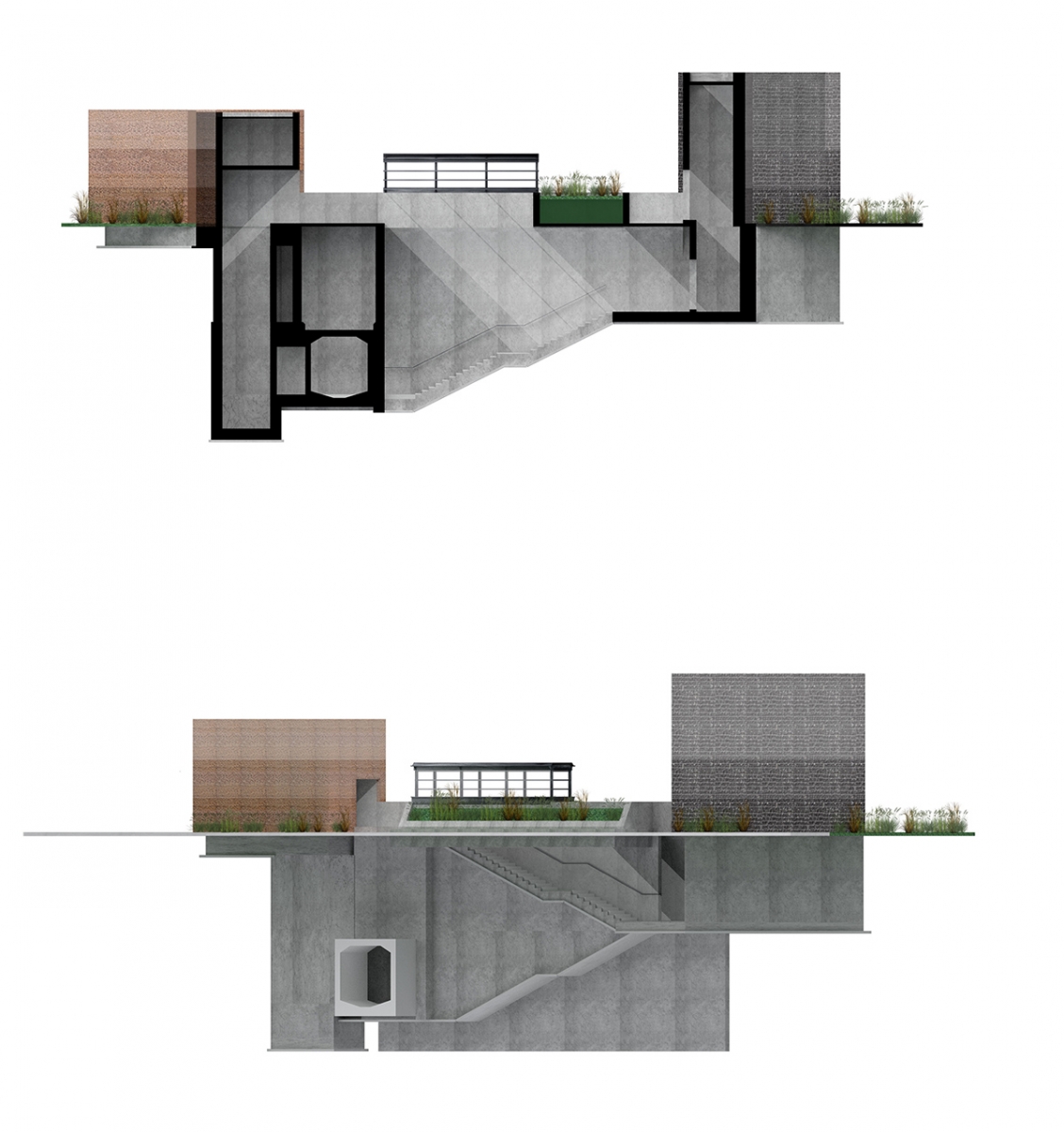

Sketch of initial proposal, Magok Cultural Center

An Awareness of the Present: Conservation, Restoration, Regeneration and Remodeling

Kim Jeoungeun: In this discussion, I would like us to consider three works by Choon Choi: the Noryangjin Sewage Walk (2020 – 2022), Magok Cultural Center (2018 – 2021), and asteroid G (2013). Each work is an example of a prevailing desire to transform infrastructure and non-building facilities into cultural spaces on heritage sites. This exists on a spectrum of various collaborations, in terms of the subjects of collaboration, such as between historians, artists, and other parties.

Choon Choi: The three tasks have something in common, in that they revitalise and renovate water-related infrastructure, such as drainage pump station, drainage facility, and drainage culvert. We communicated with the Dongjak-gu Office while working on the Noryangjin Sewage Walk project, and the Magok Cultural Center project was overseen by the architectural historian Ahn Changmo (professor, Kyonggi University). Asteroid G is a public art project planned by curator Kim Jang Un (director, Art Sonje Center), collaborated with structural engineer Lee Juna (professor, University of

Seoul) under artist Kim Sora. Kim Jeoungeun: For more than ten years, various projects such as conservation, restoration, remodeling, and regeneration have been steadily carried out in Korea. I think it would be good to begin our discussion by pointing to recent project trends or any changes in architectural attitudes and their methodological responses to such trends.

Kim Kwangsoo: I think that old buildings and abandoned spaces have grown more popular in public urban regeneration projects, as in cases such as Eulji-ro, Seongsu-dong, and Yeonhui-dong. They have risen in prominence when it comes to cafés and the ‘desire for experience’ has become widespread. I think it’s time to take a deep dive on this phenomenon.

Kim Jeoungeun: How do we begin to understand the public’s enthusiasm for old buildings and abandoned spaces?

Kim Kwangsoo: We observe the desire to escape-from-the-city among many people, from such phenomena as Jeju fever to the trend in ‘one month living in small city’ of several years ago. With the widespread use of navigation systems and the emergence of the apartment generation, they began to wander around the old villages and stone walls of Jeju Island as if they were experiencing their hometowns. Coupled with Jeju fever, there was a desire to experience buildings or urban environments constructed in the near past, rather than distant historical spaces. In any neighbourhood, streets like Gyeongnidan-gil were devised to run through the old town of this small city. Recently, the remodeling of buildings or the ‘spatial conversion for experiences’ of abandoned industrial facilities is quite common. If I define the characteristics of this contemporary situation in only one word, I might say ‘timelessness’; many desire time- travel as our present conditions often resist placement in contexts that situate them within the passage of time. As presence along with a sense of the passing of time became less clear, space became our marker of time. Therefore, there are many works that highlight the temporality of places or spaces which emphasise the affective traces of time.

Sketch of initial proposal, Magok Cultural Center

Choon Choi: I’ve long thought that the phenomenon of discovering hidden places in which to experience new spaces is popular, but, after listening to your story, I feel there’s a need to forge stronger connections with the time in which I live.

Kim Kwangsoo: Concepts such as the ‘aestheticisation of time’ and ‘museumisation of space’ proposed by Seo Dongjin (professor, Kaywon University of Art & Design) are natural desires that arise in the context of timelessness. In the past, each region built a theme park based on their traditions. A typical strategy behind the creation of a space like a theme park is the ‘time-spatialisation’. If the labour of time-spatialisation in the past was concentrated in a space surrounded by walls, such as a theme park, it now seems to influence everyday spaces. These days, when I see young people walking around neighbourhoods like Gahoe-dong in Seoul they seem to be tourists, even though they definitely live in Seoul. Instagram culture has intensified it in some ways, but I think there is a need to look at this recent phenomenon more critically.

Choon Choi: The days are gone when we were competing to see who can make ruins with a rawer quality, and lately it seems that architects are emboldened to intervene and change things with more confidence.

Kim Kwangsoo: Each site will have so many different situations and contexts whether it is to be conservated, restored, or regenerated. Even when regenerated through remodeling, attitudes will change depending on whether it is orthopedic surgery or plastic surgery. It would be great if we could discuss varied opinions and their solutions. In the past, all remodeling was close to plastic surgery.

Choon Choi: Isn’t it that we finally have a proper balance, after we’ve reached both extremes in our creation of new spaces? Now is the time for a consensus to be formed around places on the scale of an entire city, not individual buildings. The Bucheon Art Bunker B39 was unfamiliar because it was a space that was not accessible on a daily basis, but it also offered a useful springboard to thinking about the meaning of discovering such a place when looking at the whole city, and how everyday and unfamiliar spatial experiences can coexist. Instead of preserving it in its entirety, we should think about what to preserve in the context of the entire city. In the past, it was recognised only for the fact that it survived, but now it needs to develop a more profound meaning.

Kim Kwangsoo: Preservation is linked to a museumified attitudes and has ethical implications. Perhaps it is time to discuss why we should protect any one element in our shared landscape. On the other hand, I think it is necessary to seriously consider timelessness and contemporary situations when it is difficult to experience any sense of existence. As we spend most of our daily lives in virtual spaces, that is, transcending physical space through smartphones and Internet interfaces, our daily sense of space is greatly reduced.

Sketchs of initial proposal, Magok Cultural Center

Urban Infrastructure and Architectural Intervention: The Architect’s Role

Kim Jeoungeun: Choon Choi once mentioned in an interview that ‘the transformation of industrial facilities is a slightly different challenge to other kinds of transformation.’ What are the characteristics informing those abandoned or hidden spaces in cities?

Choon Choi: Infrastructure that has fallen out of use seems to be the focus when seeking to resolve the overlapping desires for ‘hidden urban space’ and ‘historic space’. I also embark on such projects by asking how architects can best approach a space where equipment and machinery are the main focal points, and what role architects can play in the absence of buildings.

Kim Kwangsoo: Noryangjin Sewage Walk is not a building, but it did involve an architect.

Choon Choi: A sewage culvert is a structure hidden underground. The process of allowing people to enter and use the space where water was flowing is different from the perspective of possession and usability. I thought it could be considered to be an architectural structure as it suggests a new way of regarding complex sites of this nature or as it offers the possibility that disused places might open up new spatial experiences.

Kim Jeoungeun: Who came up with the idea of turning sewage culverts into cultural spaces?

Choon Choi: Seoul Metropolitan Government’s Urban Space Improvement Center had already tried to build a facility at its own scale, such as the Sewerage History Museum, by taking up the land to the side of the fish market, but the plan was adjusted to the extent that we could add spaces for greater convenience, such as a café and a small exhibition space. Later, in the process of handing over the initial phases of the project to the Dongjak-gu Office, it was found that the land could not be secured, and the

plan for the convenience facilities was scrapped. The role played by the architect had become vague, and so that’s when I thought I had to get involved. As I became immersed in the project, I delineated a realm and a role. In the Flood Control Division of Dongjak-gu Office, which is the department in charge, there was a consensus that architects had to decide on the finishing materials, lighting, and accurate details. It was an opportunity to think about how architects should approach projects that don’t follow more conventional procedures, such as situations in which detailed decisions cannot be drawn.

Kim Jeoungeun: Is this a procedural problem or a work problem?

Choon Choi: I mean that although we communicated through actual drawings (within the contract system), the client did not require or need the drawings. As the project was carried out under a civil engineering contract, it was unclear whether architectural drawings were to be added. In order for drawings to be a cogent means of communication, there must be institutional support, which in many cases is not the case. These days, architects make various attempts, such as constructing a plan based on knitwork made by local residents. I think it is necessary to approach the drawing flexibly depending on a given situation, such as not being able to use it properly or focusing solely on the drawing.

Kim Kwangsoo: I wonder what the architect’s position is in this situation. Architects may develop doubts over their own identity, and it was not clear what he had to do. Which method do you think is the more desirable — persuading decision makers to expand into architectural projects or, as now, engaging in a partial intervention?

Choon Choi: This project didn’t possess enough momentum to become a fully-fledged architectural project. The name of the project was also ambiguous; the ‘Noryangjin Modern Sewage Culvert Cultural Space Utilisation Project’. Dongjak-gu Office set a budget to repurpose this relic, a modern sewage box, as a cultural space that up until then was acking in the district. However, there was no consensus internally as to what kind of cultural space would be most appropriate, and whether ‘culture’ would be represented by an exhibition space or the space itself was to be representative of local culture. There was no such discussion. It is important that the space itself exhibits its cultural credentials, but it was decided that it would be difficult to create an exhibition space other cultural materials. This was a situation prompted by the fact that there was only one staircase leading to the walkway without a building. In the beginning, it was suggested that an advisory group should be formed to tackle some of the key challenges. We searched for examples of sewage exhibition halls at home and abroad, but most of them were too large to match the conditions found in Noryangjin. At the end of the day, I was persuaded that it should be presented as-is rather than making substantial additions. In other words, I led them to decided not to build buildings! (laugh)

Kim Kwangsoo: I had a strong impression that as architect you held your power very carefully in balance with others engaged in this project. However, it is a pity that it is difficult to access because it is in a very remote location. It would have been nice if greater awareness had been raised so that daily a line of traffic would fill the route connected to the usual thoroughfares.

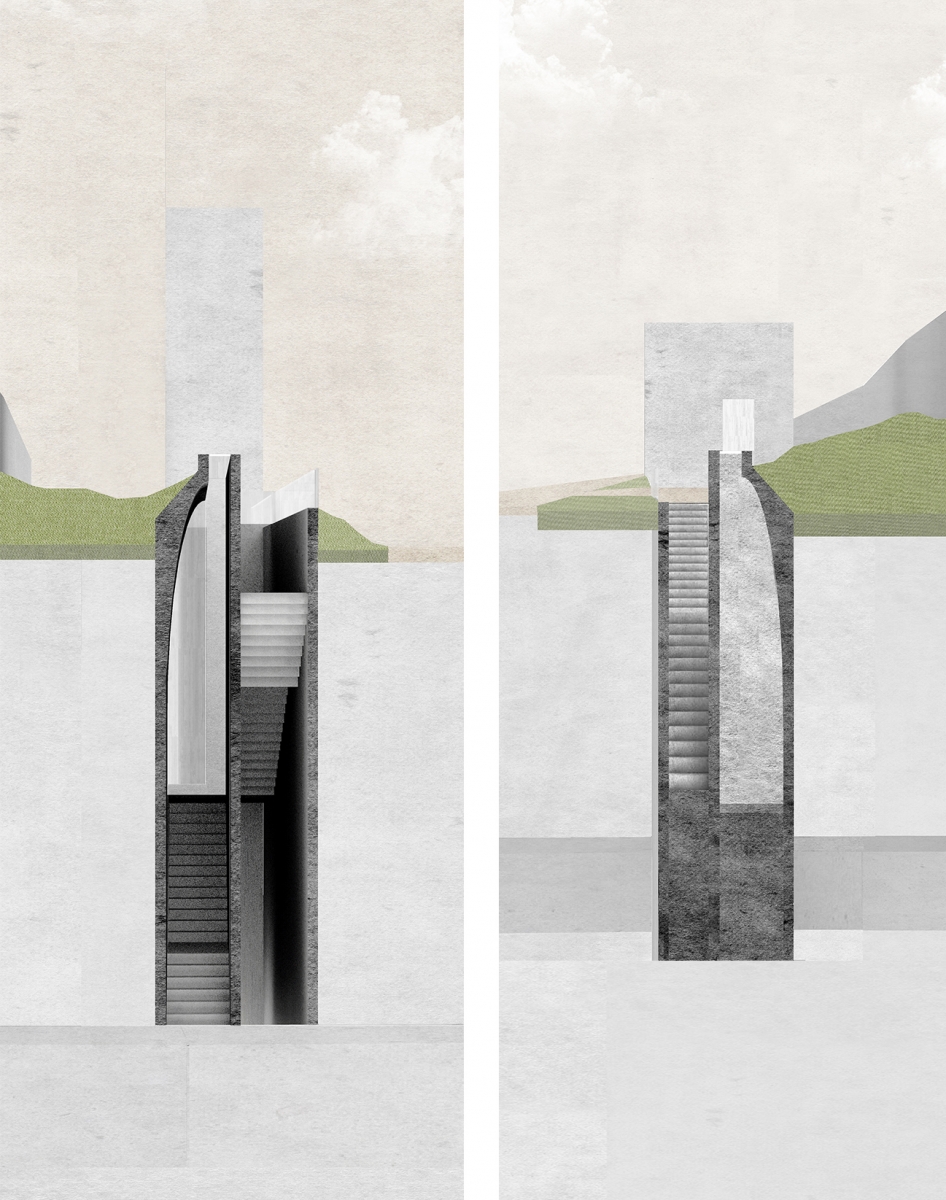

Sketch of initial proposal, Noryangjin Sewage Walk

Spaces for Contemplation and Reflection: Non-Places, Liminal Spaces

Choon Choi: Noryangjin sewage culvert conveys a sense of passing time and history, but unfortunately there is no data to prove it. Since it is a sewer, it is difficult to register it as a cultural property as there are no documents or records about when it was created, its background, or its value. I think the way one reveals a good space when it is discovered is as important as its historical significance, and I think that the opening itself as a passage is very striking. As soon as the word ‘utilise’ comes into use, programmes and management catch up and the burden increases. It would be nice if there were more empty spaces in the city for quiet contemplation, but there seems to be an obsession with filling them in all manner of ways. There are a lot of introverts out there, so why should public places be gathering places for crowds and groups? Usually, people think that a space alone is a private space, but I think there should be a lot of these kinds of spaces within public space.

Kim Kwangsoo: The most interesting thing about this is that it is a space that excludes the logic that has been running rampant in the Korean architecture field. It was not a building that was in the shadows, nor was it a space that was used, but it was a facility that was completely concealed. It was not an object of interest, but now it has become meaningful as it has been rediscovered. Generally, in public projects, programmes, degrees of usability, and narratives are used to convey meaning, but I think this approach better because there are no such grades. It feels good to ‘keep the old stuff in place’, but the question of ‘what is it for?’ keeps coming up. This is new because the sense of the ‘non-place’ makes more sense than the necessity of ‘making a place’.

Choon Choi: Dongjak-gu Office hired a separate firm to address the Architectural Attitudes:storytelling aspect of the project, but few stories were found because it did not exist as a place.

Kim Kwangsoo: It’s easy to tell stories about the spaces occupied by humans, but as this is a non-place such storytelling efforts are difficult. Instead, the space itself inspires a strange approach to narrative. When I first saw this place in pictures, the ‘liminal space’ came to mind. It was a different world from this world, but it felt liminal, with no interaction and no people. A space where concrete, stone, and bricks speak features an aspect that allows people to imagine a narrative instantly.

Choon Choi: This seems to be an area that cannot be understood through reason. For example, looking at a space from the perspective of water, or the fact that the train passes by, seems to prompt a narrative. When a person stays in this basement for a long time, the sound of dripping water and the feeling of the damp air becomes overwhelming, giving a sense that one should not enter. Observing this space, I also felt that cities might not be for humans alone.

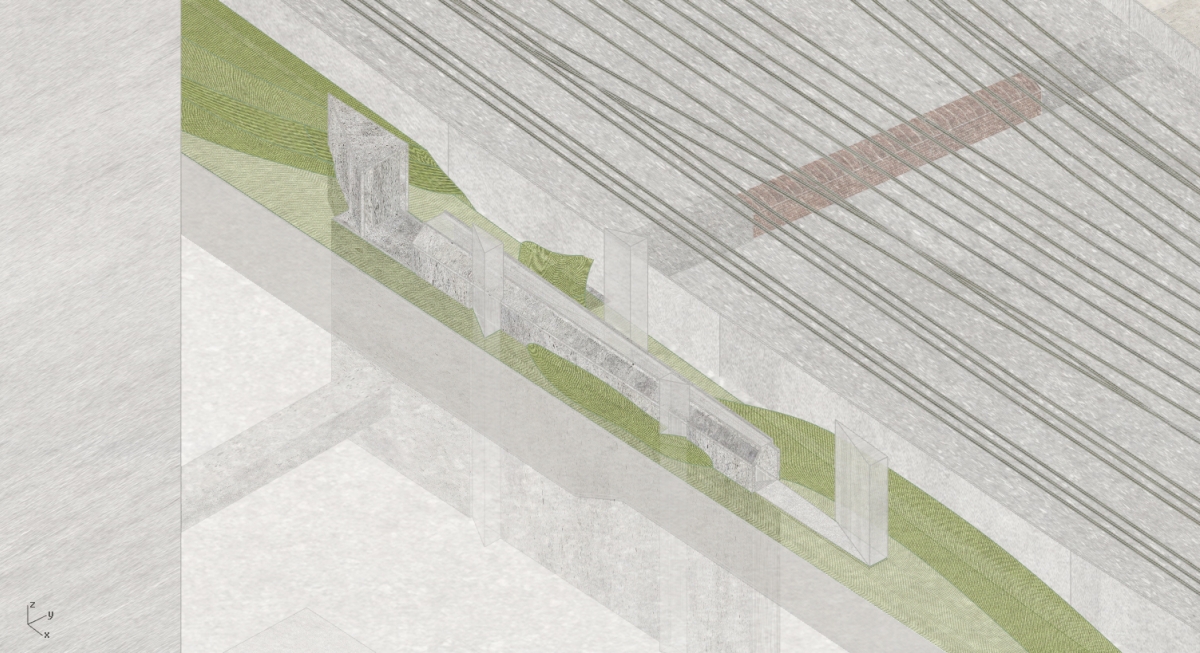

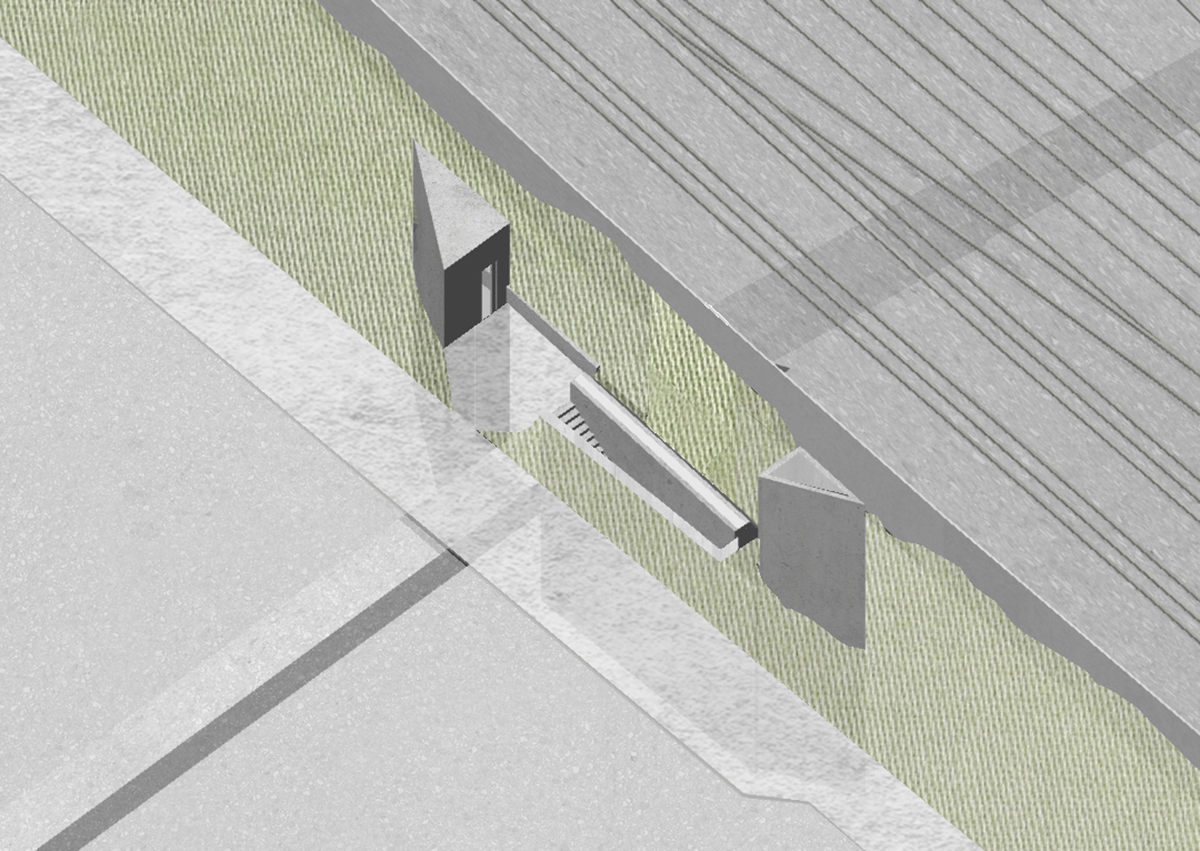

Sketches of initial proposal, Noryangjin Sewage Walk

A Vanishing Architecture and the Vanishing Architect

Kim Jeoungeun: I believe this brings us to the Magok Cultural Center.

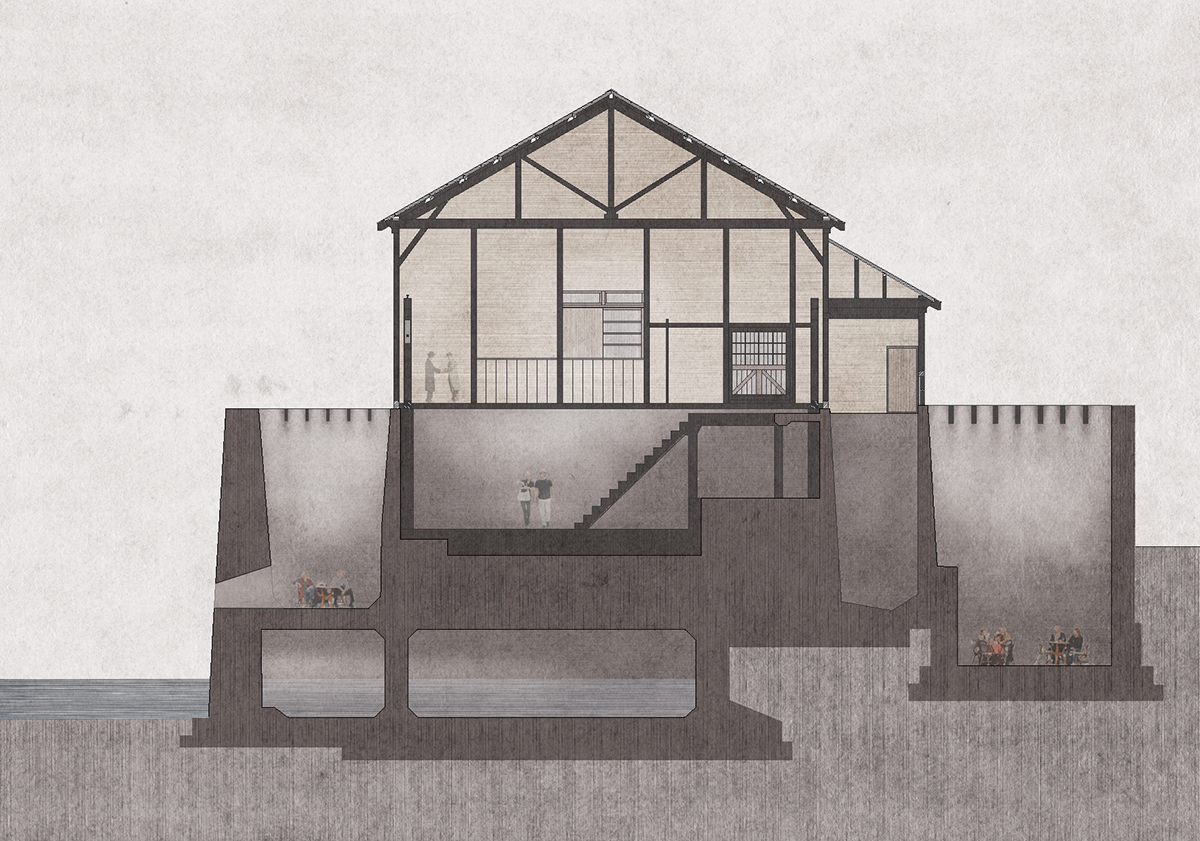

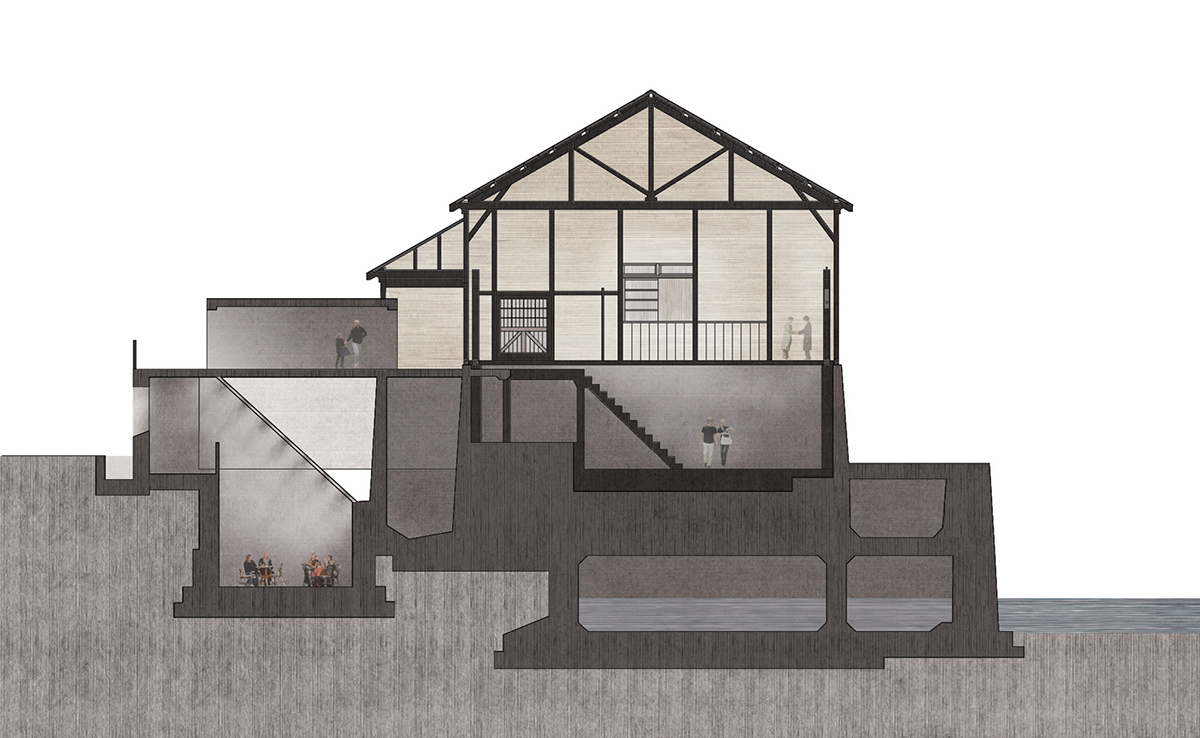

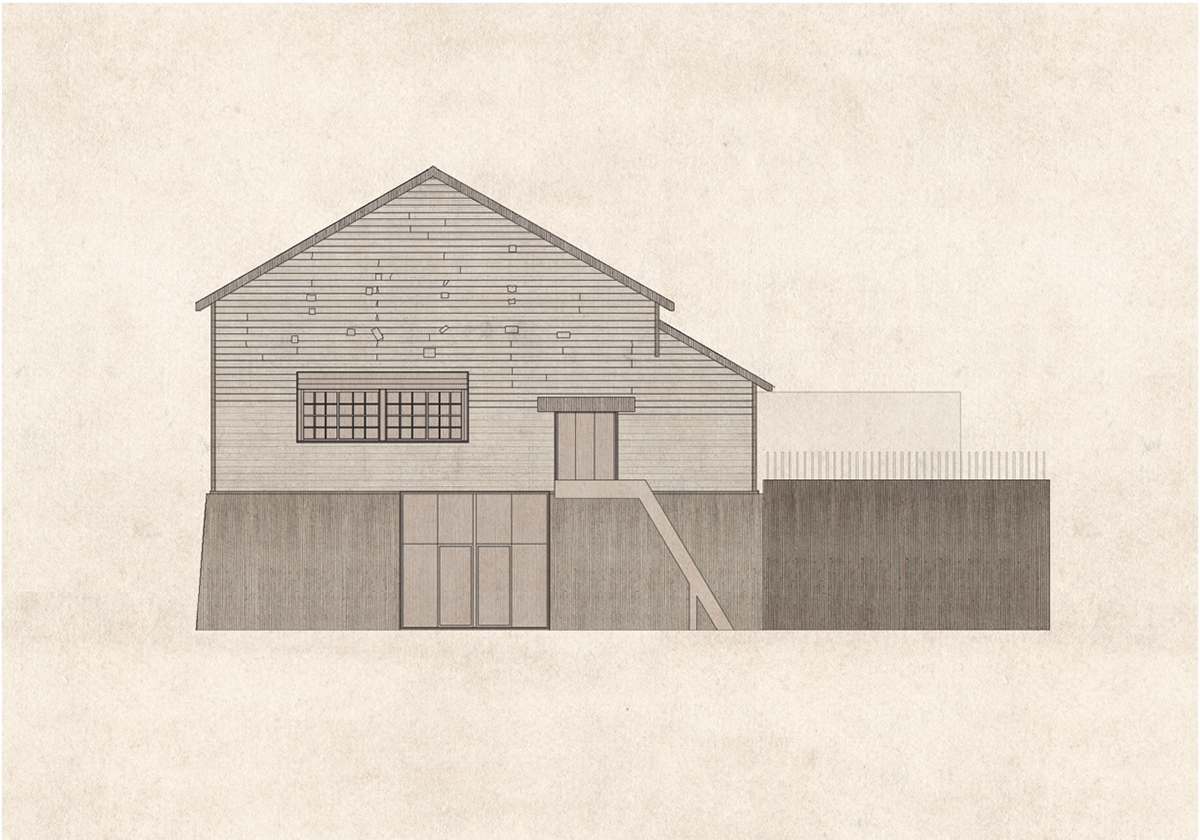

Choon Choi: From the outset, I could see that the Magok Cultural Center was on a different plane to the Noryangjin Sewage Walk. There was a solid genealogy and record of the building; it was easy to register it as cultural property because there was a record of who built it in the 1920s and the decisions made about its form. Ahn Changmo, who was in charge of modern architecture research, wanted to preserve the surrounding buildings in their entirety, but in order to be recognised as a Registered Cultural Heritage Site, it has to have a visible structure such as a wooden structure. It was difficult to designate simply because it was an old official quarter. The logic that a place can only be preserved if it is connected to its surroundings makes no sense in the field of cultural heritage. After the Magok Cultural Center was designated as Registered Cultural Heritage Site, the nature of the ‘preservation’ was determined. Next, there was discussion about the use of the site, and the opportunity closest to my aims was that the wooden structure on the upper floor was considered cultural property, while no one cared about the lower structure. The waterway, which was buried underground and which no one could see, was an area in which people could concentrate on the space. First of all, I looked at the old and original drawings and worked hard on the design. Rather than changing something, we figured out what could be done in the space, and the size of the rest areas and exhibition spaces underground, and arranged the structure of decks and roads accordingly. But when we dug into the ground, the space itself was so cool that I didn’t have much to do. It suggested that architects do not necessarily have to build a thing in such an architectural context.

Kim Jeoungeun: What did you do after you removed the sediment from these underground spaces?

Choon Choi: It was my job to edit, so that only the space itself remained. If exhibitors had touched this space without the influence of an architect, they would have created rooms and the interior would have been altered to a much greater degree. I believe architects are capable of arranging spaces much more coherently when they are involved. It also took a great effort to prevent lighting and furniture from being installed on the ceiling. There were many opinions such as exhibiting throughout the lower space, adding something to the room, and excavating more of the land but the process of persuading them to say ‘this is enough’ at the right moment was crucial.

Kim Kwangsoo: I really like the atmosphere of the underground space, but why didn’t the café planned here come to be realised?

Choon Choi: It is not easy to maintain a good first impression, but as a means of persuasion, I tried my best to express my sense of this space through images (drawings). In fact, most people draw pictures knowing that they can’t realise the original plan, but in the knowledge that here is a freedom of imagination. (laugh) It’s unfortunate that they couldn’t create a rest area as planned, but at the beginning of the project, they decided that they didn’t need a café. Because of the nature of public works projects, it was also difficult to determine the overall cost of the project in terms of the underground space.

Kim Kwangsoo: Why do you choose not to introduce it as your own work, as you were actively involved in the design.

Choon Choi: The Magok Cultural Center and the surrounding park was already in existence, so it’s hard to claim it as my work. As many people worked together to ensure that the restoration of the old building was successfully executed, it was only appropriate that authorship is spread across a number of parties. I tend to respect other people’s opinions and follow them without stubborness when working collaboratively. When I participated in asteroid G, I saw artist Kim Sora enjoying the process by which many people’s decisions were integrated into the overall schema. I believe that architects should not be responsible for every decision or that others should enforce that expectation.

Kim Jeoungeun: Working with Kim Sora seems to have influenced your attitude as an architect. How did asteroid G start?

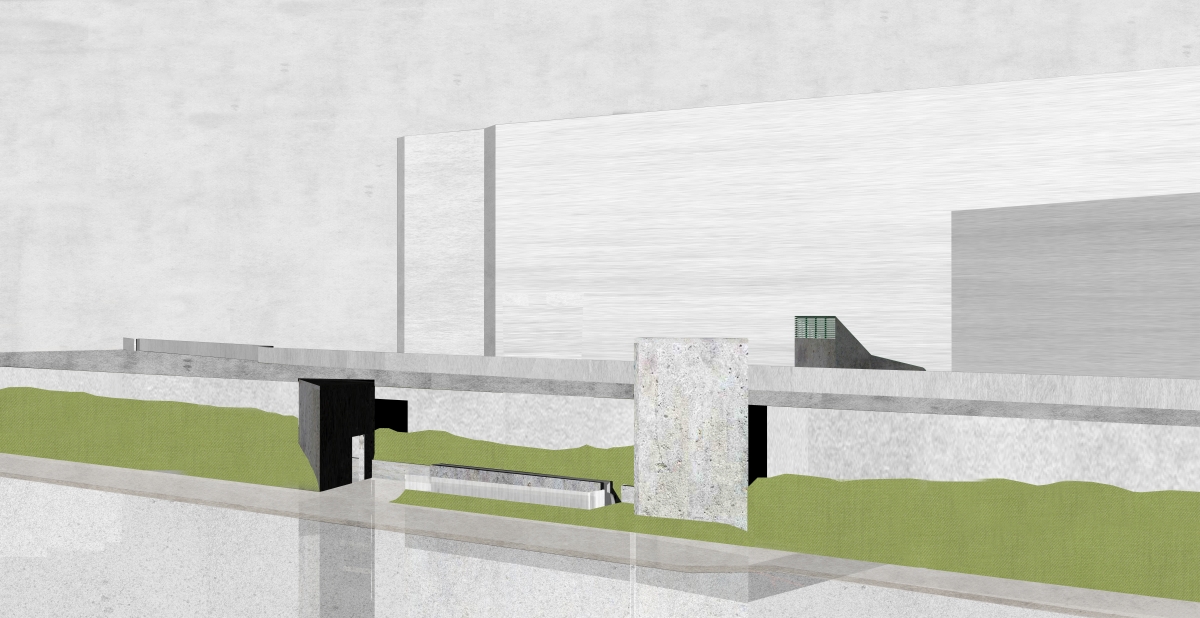

Rendering image, Noryangjin Sewage Walk

Choon Choi: In 2013, Arts Council Korea planned a public art project called ‘ARKO Urban Park Artro’ for urban infrastructure. As a project that offered the opportunity to experiment with the roles an artist can play in public space, it took place as a competition to solicit artist proposals for specific sites. The site of asteroid G is the Geumseong drainage facility in Gongju. The winning proposal, planned by Kim Jang Un and led by Kim Sora,

was to fill the concrete floor of the fence-enclosed drainage station with a surface resembling the topography of Gongju. However, in the process of negotiating with Gongju City, the plan was completely revised, and everything returned to the original outline. Face with this, we proposed two new alternatives: to open up the fenced area and build a bridge through which residents could cross this site more conveniently, or to build a structure in which stones picked up in Gongju were embedded on one side of the drainage stations like meteorites.

Kim Kwangsoo: Did you design this bridge yourself? How was the cubic modular pavilion-like climbing frame constructed?

Choon Choi: I think we should make it known that Lee Juna, who was tasked with overseeing the structure, was in charge of building the bridge. I only drew plans! (laugh) Kim Sora said she wanted to put a huge stone sculpture inside the drainage stations, and she asked if people could be allowed inside, so we built a wooden structure to form a framework. Originally, the structure was supposed to be covered in a stone shape, but when the sculpture was completed the budget had been used up, so the surrounding structure ended up like a climbing frame. At the time, Kim Sora said, ‘we managed to secure something, it’s no bad thing for us to stop here’ and I liked her attitude.

Kim Kwangsoo: It’s like ‘let it be’, like she didn’t have any attachment to the work as an artist.

Choon Choi: Most conceptual artists, including Kim Sora, seem to place emphasis on the working process itself, unlike artists with a specific medium of expression, such as sculpture or painting. Rather than dealing with a specific object, it is considered as a means of experiencing the process. Ultimately, I think that the goal of art is to be a social act, rather than an aesthetic outcome.

Kim Kwangsoo: I have a very similar feeling when encountering the architectural attitude of Choon Choi. Looking at the Magok Cultural Center or the Noryangjin Sewage Walk, I get the impression that the architect is trying to remove colour. This seems to feature in one’s sense of the legitimacy of the project, for example, the legitimacy of erasing the colouring of the architect in terms of preserving the character of the original.

Choon Choi: It’s more convenient to erase yourself. It’s because I didn’t form this place, and it’s a place regardless of my presence.

Kim Kwangsoo: That attitude is also a desire. The desire of absence to remove oneself. In our private conversations, I thought to myself ‘Is he going to do it or what?’, but you seem to be more hesitant. I don’t think such an attitude can be evaluated as good or bad. I’d like to acknowledge that it is sufficient to possess a certain type of attitude that values the structure. However, it would be advisable to grant meaning to yourself and to your decisions, and to adopt a clear attitude, but if you had no choice but to remove onself from the equation, then the meaning is different. Personally, I feel that both stances coexist.

Rendering images, Noryangjin Sewage Walk

Choon Choi: Rather than expressing my presence an architect, I think I focus more on revealing that ‘the work would have gone in a different direction without that person, but it’s possible because of him.’ I define myself as a person who would be beneficial by just being proximate.

Kim Kwangsoo: Are you the catcher who protects others as in The Catcher in the Rye? (laugh)

Choon Choi: Though the role of the catcher may seem small, it can be an activism in that one knows which direction he/she should pursue. Kim Jeoungeun: I also think this might be the right role for our current urban situation.

Kim Kwangsoo: The attitude you have described is similar to the coordinator’s role. The integrity or completeness of the building itself is likely to fade if you take the attitude of a coordinator who accepts the many needs of the surroundings. However, Choon Choi’s works are very sensitive in their detail. I sometimes wonder whether this is because you have impressive skills as a coordinator.

Choon Choi: Even the artists with whom I have a personal affinity are usually people who work at less rather than more. Making something less is also a significant aesthetic approach.

Kim Kwangsoo: Lastly, I am curious about topics such as nostalgia for the public arena, the aestheticisation of time, and the process of extinction. How do you feel about nostalgia? I wonder if you feel nostalgia, and if so, how it relates to themes of unfamiliar architecture?

Choon Choi: I don’t think they are related. Nostalgia seems to have an overly appreciative relationship with the past, and I tend to distance myself from it. It’s not something you have to feel in the city. It is a non-spatial sensibility that individuals own, like memory, but it is doubtful whether it is architectural to elicite nostalgia.

Kim Kwangsoo: In this context, the Magok Cultural Center, a wooden building that offers an impression of the styling typical in the Japanese colonial era, is an example of a structure that stimulates nostalgia. Aside from the above-ground aspect of the project, I wonder whether the underground part was approached with a particular mood or sensory apprehension in mind, such as the uncanny or unfamiliar.

Choon Choi: That’s right. I want it to be reproduced as if no one had interfered, as if it were a real prototype. I think revealing what’s gone and what’s still left is different from experiencing nostalgia or uncanny feelings. Rather than returning to its historic state or revamping it, I wanted the feeling I felt at the beginning to be refined. It feels like cleaning up. The first work I performed after returning to Korea was a project that transformed the building of the former Defense Security Command (presently the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul) into an exhibition space. Before remodeling, I found a corner space under the stairs and went down and cleared the space. It felt really good, but the best thing was when the carpenter who was on site came in after it was cleared, put nails in the wall and hung up clothes. It’s not design, it’s cleaning, one big clean up.

Kim Kwangsoo: Cleaning seems to be the key to the this project and its identity. However, isn’t cleaning an activity that has no end?

Choon Choi: That’s right. It is a repetitive and habitual practice. Most jobs are fine as long as you clean them well. When we were building workshops in Haebangchon, the residents who didn’t like our work did express their gratitude to us for sweeping the stairs so diligently.

Kim Kwangsoo: Should I refer to you as the janitor of the architectural field? (laugh) I hope you continue to work in this direction and make your voice heard.

Section sketch, Noryangjin Sewage Walk