I was able to visit two houses in Seoul’s outskirts designed and supervised by the principal of guga urban architecture, Cho Junggoo, during a two-day visit. I was very lucky to have a tour around two houses built with his talent and care. In this article, I would like to give you an idea of what came to mind during these visits; what I saw, what I heard, what I felt, what I thought, and what I agreed on. Before proceeding further, I would like to ask for your patience and understanding for my reasons not to write an architectural critique. It is closer to reportage or a travel essay. Before I get to my central points, I would like to tell you the story of my first visit to Korea, now more than 40 years ago.

In the early autumn of 1977 when I decided to travel Korea, Yoshimura Junzō – the principal of Yoshimura Junzō Architects in whose employment I was engaged, a respected teacher of mine – introduced me to the work of Mr. Kim Swoo Geun, an architect who passed away. When Kim studied at Tokyo University of the Arts, he was not only instructed by professor Yoshimura but also granted a reference from the professor. It is safe to say that the professor was not only a great teacher but also a savior to Mr. Kim.

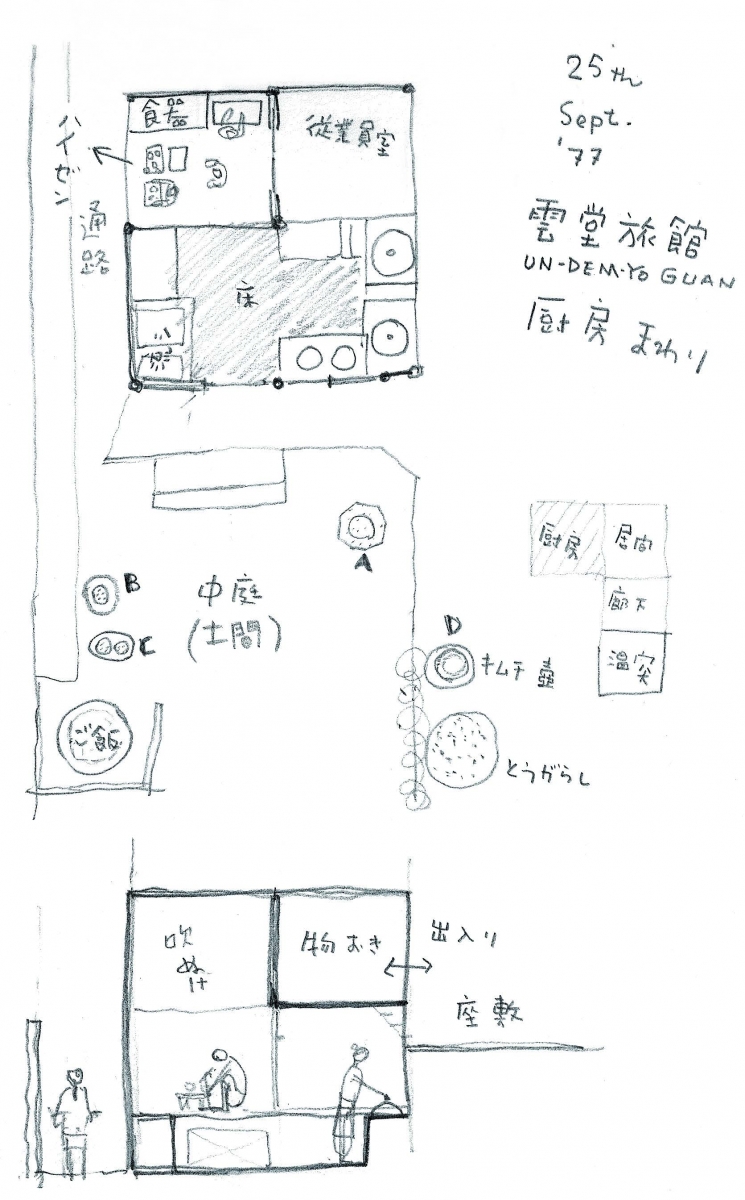

Thanks to professor Yoshimura’s request over an international phone call, I received great hospitality from Mr. Kim. Out of many occasions, what I have been most grateful for is that we were able to stay at a hanok inn called ‘Undang-yeogwan’ near the SPACE headquarters (Kim’s architecture office). I had been very interested in the woodwork and pottery of the Joseon Dynasty since I was very young. During this trip, however, my interests shifted from Korean artifacts to architecture as I was inspired by the houses of the folk village in Yongin. I also cherished staying at the hanok inn, an urban courtyard house. I was impressed by the cosy thatched roofs of folk villages, the ondol rooms with hanji (Korean paper) on walls and ceilings, and the sectional variations in a compact floor plan. I was fascinated by the composition of the space in the Undang-yeogwan as well as the stone-walls enveloping the outside. It was a typical urban courtyard house with several courtyards inside the house.

For example, the small ondol room where I stayed was connected to an additional courtyard that could be accessed through another courtyard in front of the main entrance. Then, after passing through the room and exiting the narrow passage between the buildings and the wall, there is another courtyard with a kitchen where people were always preparing for meals with loud chatter. On the sunny maru (a wide wooden floor area) adjacent the courtyard, some workers sewed guest bedding. It was surprising to see people working so diligently together as one, and I was inspired by this workspace, a courtyard also nimbly ‘working’ together with them. As I wanted to remember the moment, I captured the scene in a sketch and even took photographs.

The real story unfolds from here.

In the early afternoon of the 24th of February, I was joined by Cho Junggoo, at Gimpo Airport, and headed for Paju k House by car. As I had seen photos and drawings in advance, I was able to quickly discern Paju k House when nearby. From the west road, the two simple gambrel roof sides overlap one after another, creating a kind of rhythmic feeling. That the roof of the main building is almost symmetrical, and that the roof of the building in front is asymmetrical, on the other hand the roof on the north side (roadside) does not even have an eave compared to the immensely protruded on the south side, contributes to an overall sense of dynamism by intentionally breaking the balance.

This part of the design seems to have succeeded as intended, but in my personal opinion of the site, the wall could have been pushed to the end of the eaves ― more likely a gutter ― like the first floor if the eaves have to be placed on the second floor only, so that people could see the eaves from the outlook.

Moving forward, we were on the road on the north side and gazing up at the façade of the house. On the right side of the façade, there is a low wall made of bricks ― the outer wall of the building ― and a symbolic pine tree, accentuating the charm of the façade. The façade design is properly controlled and communicates a serene feeling. The minimal number of windows on the walls made of gray and white bricks, and the wooden garage shutters and front doors, and the windows of the traditional Korean rooms, all three of which are balanced like in the paintings, give the impression of simplicity, splendour, and calmness.

To me, the simplicity of Paju k House, all of which was made of single brick materials, seemed to play a role of a ‘critique’ of the so-called ‘luxurious mansions’ which look rather disorderly in the neighbourhood. Once again, I felt that it was more important than anything else for both architects and clients to be humble and to pay homage to the ‘landscape’ in order to create a dignified, harmonious and mature residential district.

Paju k House

Enough about the outside; we finally entered inside. Unlike the somewhat closed atmosphere of the outside, the interior was surprisingly open. The moment you enter the living room from the front door, there is a spacious floor and a well-kept lawn yard in front of you. The spatial experience was obviously directed by the architect, but I couldn’t help but wonder if the owner couple caught the architect’s intention better than anyone else. This was clearly shown when I asked the client couple ‘how to choose an architect’, and the trust in the architect was clearly understood by their answers. This large and cool living room space flows smoothly into the kitchen and dining area on the left. I really liked the flow of this space.

In fact, the couple asked for a ‘house in which one might sense the emotional resonance of a hanok, but not an actual hanok’. According to Cho Junggoo, he could address this issue by exposing the rafters and aligning wooden louver with the angle of the roof to create the living room space with daecheong (the main hall of wood-floored area in a hanok). It offers the impression that the Korean traditional housing method was reinterpreted for substantial utility given there is a greenhouse (atriumlike madang) in front of the dining area, a multi-purpose room in front of the kitchen. The most ‘hanok-ish’ place is the Korean style guest room to the north of the living room. It is a calm space with a private yard on the west side, a small room perfect for quiet reading.

At the entrance to this traditional room, two pairs of Korean-style windows are exquisitely arranged, balanced on one side of the large living room wall. This lovely design window felt like it symbolised not only the Korean style room but also ‘Style Korea’ itself. This story could be long-winded so let me fast forward to the second floor and focus more on the outside. I was able to go outside and see gray bricks that were very unique from a distance. I heard that this brick was imported from China and is said to have been collected from an old building after it was demolished. It is said to be a relatively easy-to-obtain material and known as ‘baekgo’ (antique white), but since it is an old material that is tainted with mortar on the surface, has an uneven color, and even cracked corners. It looked a little messy upon completion of the construction. The client couple couldn’t dismiss the messiness, so the exterior wall was polished with a grinder to make it as clean as one sees it now.

I agree that the bricks and textures of the current condition are incredibly beautiful, but I would have preferred to ‘see the original conditions’ for my own good. The contrast with the indoor space might become clearer without polishing the old bricks, leading the impact to grow even stronger, therefore something unexpected or the new value might have been added architecturally.

When I returned to the garden once again, I found two chairs all of sudden in front of the southern wall. As I was looking at them unconsciously, the Japanese staff from the guga urban architecture said, ‘It is one of our most joyful moments to sit side by side and look at the house’. At that moment I noted, ‘Oh, I am experiencing a really good house project in which the architect and the client truly communicated’. The sense of accomplishment soared in my heart.

***

On the second day, I visited a house with a unique name, a workshop house 10M4D in Icheon’s ceramic art village. In his car heading to Icheon, Cho Junggoo told me that the name means ‘10 months out of 12 months a year, 4 days out of 7 days a week,’ which translates to mean that they will have a rest ‘Two months a year and three days a week.’ 10M4D, nestled in a round corner of a quiet residential area. I got the impression that it has become the ‘landmark’ of the neighbourhood.

With single-story buildings and corridors near the road, the two-story building is located about 6m above the road, providing a relaxed and open sense of space. That’s why it’s so relaxing for the beholder, giving the viewer the pleasure of looking at the building as it rounds a gentle curve. This can be regarded as a ‘courtesy’ made by Cho Junggoo who put the word ‘urbanism’ in his company name. And I would like to speak highly of his attitude towards making beautiful scenery.

The day was unfortunately rainy, but I had a strong sense of the extraordinary ‘pride’ of Cho Junggoo in his exterior design, while looking at the light corridors supported by the columns and the stark contrast of the heavy brick walls, the courtyard raised 50cm above the road and the garden created by lowering one step inside, and the courtyard for the exterior design of the building, such as a working yard.

10M4D is a single-story building and a two-story building that face each other with a courtyard in the middle. The two buildings are connected by a corridor. He had perhaps reviewed a lot of site plans and spatial compositions before making his decision. Looking at old neighbourhoods in Seoul, throughout multiple surveys and remodeling projects of traditional Korean houses, Cho Junggoo has been actively pursuing the madang concept in his own house. In addition, the drawings clearly show that 10M4D has been trying to bring about the fruits that have been accumulated on the theme of madang. The day’s tour began at the embroidery workshop, a single-story building.

This is a workshop and retail space for the wife, who is an embroidery artist. The building is closed in the direction of the road but open to the courtyard. I don’t know if it’s the nature of the embroidery or the personality of an artist, but there was a bright atmosphere inside.

The fact that it is a wooden building and the materials that are finished with wood is probably another factor that creates a warm atmosphere. If you go outside through the door inside the workshop, it is a yard 45cm down from the courtyard, and also a passageway to the pottery workshop space. And, as it implies, this is a madang (for work), a group of chocolatecolored kimchi jars was placed in the yard.

Keep on searching, there I found the pottery workshop with the reinforced concrete structure, which is located on the first floor of a two-story building. The interior was unified in a cool gray tone in contrast to the embroidery workshop. The space was a creative workspace as well as a living area for the client’s daughter.

I had to move quickly to the second floor because people were busy inside. If you enter the front door and walk up the gentle slope of the stairs, there is the living room of this house.

I don’t know if it was due to the narrow exit or the long staircase room, but when I climbed up to the stairs, the second floor was brighter and more open than expected. In fact, space, where the shape of the gambrel roof was revealed, was both cool and spacious, and the atrium facing the southwest was covered with glass roofs, and the natural light was so bright that it could not have been considered a rainy day.

10M4D ©Yoon Joonhwan

On the second floor, there are the master bedroom, living room, and the dining room and kitchen are surrounded by an atrium in a U-shape. Standing in the middle of the living room and looking from left to right to 180 degrees like taking a panorama shot, you can see that Cho Junggoo designed this atrium, modeled after the traditional Korean madang. This atrium, which is both external and internal, is actually a madang either. The atrium is designed to be simply opened and closed, with a large sliding door made of hanji windows that controls light and temperature throughout the year.

I experienced the pleasure of slowly walking around and viewing the indoor space at certain points in this house. It was when I came out of the son’s room on the east corner of the building. And when you stand there, you see stairs coming up on the right side, you see the back of the couch in the living room, you see the atrium on the left, and you see the dining room on the other side of the slope, overlapping with the kitchen on the other side. To put it simply, if you look diagonally into the interior, you could definitely sense the spatial composition and how they have been connected. From a different perspective, I looked to the son’s room in the opposite direction from the kitchen, and then I saw the atrium on the right, and family and guests chatting in the living room, and the railings of the stairs, and the son’s room inside of them. The joy of site visits of the housing projects lies in this small discovery of my own. And if you could deduce the architect’s intention, and take a step closer to the essence of the house, the journey itself deserves the name of travel.

10M4D ©Yoon Joonhwan

After browsing the house, I joined the team and had a nice talk. Thankfully the moment came that Cho Junggoo could tell why he was inclined to introduce the Korean tradition of madang into modern housing projects. So far, I heard the word madang many times from him, but honestly, I didn’t know the exact meaning. So I decided to ask Cho Junggoo and Japanese staff Yoneda Sachiko, ‘How do we define a madang in Japanese?’ The two of them hesitated a little and replied in unison, as a ‘working yard’. As soon as I heard their answer, I had a flashback to where the aunties work together in the courtyard (=madang) at the hanok inn Undang-yeogwan on a beautiful day in autumn 42 years ago.