The Seoul Compact City International Design Competition was hosted by the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) and the Seoul Housing and Communities Corporation (SH) last year, in the context of ‘re-creation of urban space’. The nominated site was in Sinnae-dong of Jungnang-gu, inclusive of the Bukbu Expressway. In other words, participants were given the task of creating a public housing complex on top of an artificial space over a 500m long and 50 – 70m wide highway. Architects also had to present a master plan for covering the wider area, including the Jungnang Public Bus Garage, Sinnae Train Depot for Line 6, and Myeonmok Light Rail Depot.

The winner was the ‘Connection City’ by the POSCO A&C Consortium – which comprises Unsangdong Architects, Jang Yoon-gyoo (professor, Kookmin University), POSCO A&C, Yooshin Engineering Co., and HANBEAK F&C. Unsangdong Architects and Jang discussed the concept and the design behind the project, and POSCO A&C, who led the project, considered other contributing factors in the plan.

Interview 01_ A Proposal for New Terrain in the City

Jang Yoon-gyoo (professor, Kookmin University), Shin Changhoon (co-principal, Unsangdong Architects) × SPACE

SPACE: The design concept of connecting these disconnected areas is quite intuitive.

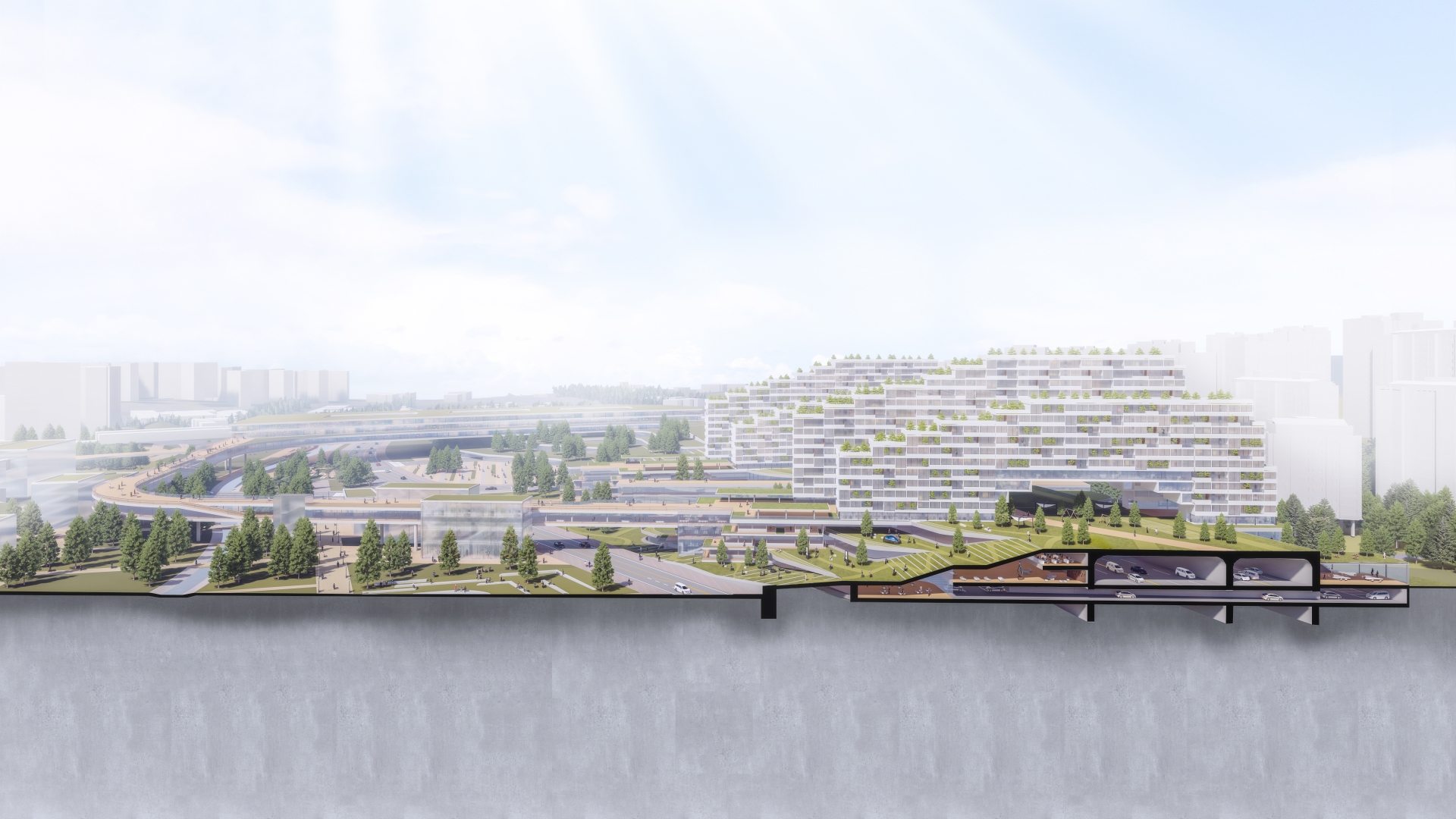

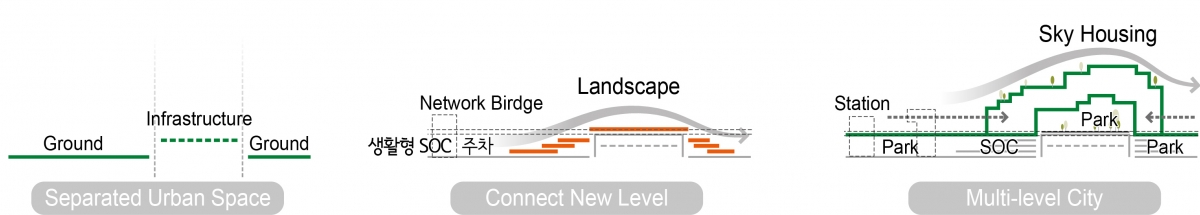

Jang Yoon-gyoo (Jang): I still remember the diagram presented by the government of Seoul. There was a tunnel structure and a house placed right on top of it. If we were to follow this direct metaphor, vibration and noise would have been transmitted directly to the housing above. We have, on the contrary, separated the housing structures from the foundations. Not only can they build up the optimal structural systems, but they can also create a huge park on the top of the highway. It was the starting point of the idea. The plan evolved as the surrounding apartment complex and Sinnae transportation hub was linked by the bridge. The critical point is that the residential area has become a part of a ‘system’ connected to the land.

SPACE: It looks like you may have alighted upon a new paradigm for developing cities. Can this approach, building above the road, be universal?

Jang: One of the ideal options can be that the Gyeongbu Expressway. This immense infrastructure cuts off the Gangnam area. It would be feasible in terms of economy. Interestingly, we are not the ones who invented the house-above-the-road paradigm. We can find it in Sewoon Sangga by Kim Swoo Geun. But were we short of land at the time? (laugh) Of course not. We can assume that it was difficult to develop dense and low-rise building districts when new buildings were firstly introduced to the city centre.

Shin Changhoon (Shin): No site means no base for a building. It became reality as 23% of the mega city Seoul is covered by road networks. It means that architects, civil engineers, landscape architects, and really all professionals should work together to exploit the possibilities of places that seemingly are not appropriate terrain for construction. It requires completely different approaches from the conventional: architects design buildings on the ground following zoning plans. This project was innovative in this regard.

SPACE: The structural issues had to be addressed first to realise the concept. How did you take care of them?

Shin: There were no cases in Korea in which both structures were combined. It might have been possible abroad, but this will require extensive research.

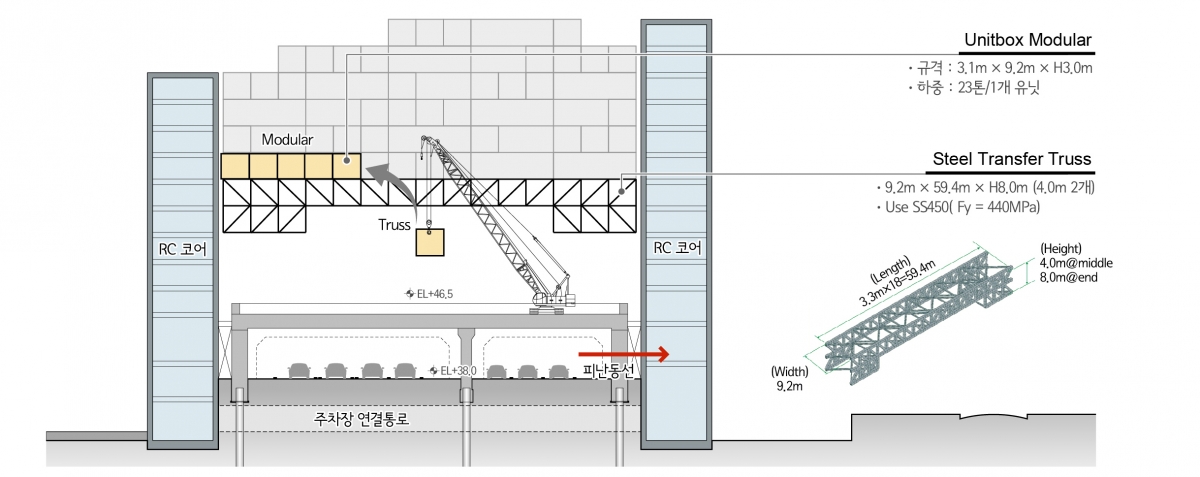

Jang: Considering the road width, a truss structure was a solution. We contacted POSCO A&C to collaborate on the competition proposal, as they have modular design know-how, and so we were able to take advantage of a truss structure. It is important that the plan is not about the house next to the road, but about the house above the road. Civil and architectural structures coexist but can be constructed independently. I was sure that it would be impossible to transcend structural concepts from scratch.

Multi-layer process

Hybrid-structure system

SPACE: Did other teams fail to come up with such an intuitive plan due to structural problems?

Shin: The site looks like an empty land from the map, but when you go there, you see a fence on both sides of the site. Residents of the Sinnae 3 District are against the construction of public housing. They say the new buildings will block their views completely. We promised that we would raise the standard of living by linking the neighbourhood. Our plans also tried to maintain as much of their view and privacy as possible, even if the buildings were built.

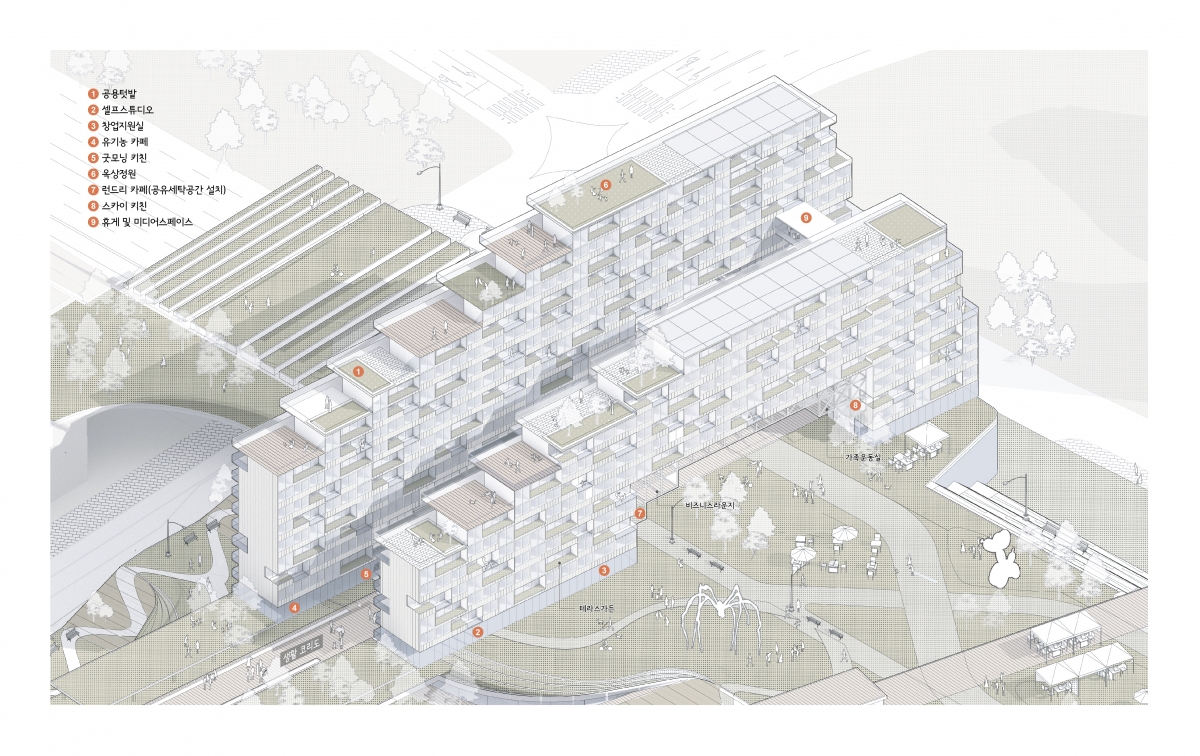

Jang: Maybe it was because we wanted to develop a new prototype or a system rather than focus on the layout. The winning project has a low-density accommodating only about 1,000 households. I think it is the right decision to maximize density at the expense of covering up entire roads. We are able to do it, simply adding a set of such systems. In this system, the community is also very important. Most residents are newlyweds or young people in small residential units. So, we introduced public and shared spaces where they can socialize.

SPACE: There were many questions regarding the building’s layout which combines two buildings into one unit in the final review.

Jang: First of all, when it comes to the building’s south-facing alignment, we took the side of those who take it seriously. It could of course be changed in the course of the realisation.

Shin: The privacy issue was also a concern, but we put more emphasis on the activities inside than on the privacy between buildings. If the bridge connecting the apartments in between is used and activated by the neighbours, wouldn’t public facilities that function as a common place rather than private one become a residential space?

Jang: I believe that it takes about 300 households to form a community and become a self-sufficient city. As I said earlier, we also considered the characteristics of residents. But why don’t we let the first things come first; it is important to give young people chances to run into each other. Aren’t young people left alone these days? Don’t we need to build a functioning social device first for the younger generation to find their beloved other half before we build apartments for the-already-betrothed? (laugh)

SPACE: If the project is realised, the city would look a lot different.

Shin: The project was significant in that it expanded the realm of architecture. If these kinds of projects continue to be embarked upon, they lead us to view the city from a different perspective, in cooperation with experts from various fields.

Jang: Developing a new type of land needs a progressive approach. This is an area where architecture can really stand out. If there is more land in this condition, there will be more opportunities for us to challenge architecture. One more, the current apartment complex was nothing but a gated community. Our proposal is an elevated housing complex with the ground level open to the public. If it is realised, the paradigm of the apartment block will undergo a fundamental shift—from a gated community to a public place.

Interview 02_ The Conditions Required to Realise the Proposal

Kim Deaone (CEO, POSCO A&C), Seo Hyoungjoo (senior manager of Design Group lll, POSCO A&C) × SPACE

SPACE: How did you understand the guidelines in this design competition?

Kim Deaone (Kim): There have been many efforts made by the government of Seoul regarding the availability of housing. However, an insufficient amount of land has made it difficult to execute large-scale housing projects. It means that a paradigm shift is needed. Moreover, Jungnang-gu, where the site is located, is considered one of the areas with smallest number of welfare facilities for residents in all of Seoul. It seems that we are all in need of an opportunity to resolve both housing and welfare issues at the same time.

Seo Hyoungjoo (Seo): It was important in this competition to deal with lifeenhancing SOC facilities, in which a variety of residents around this site could come to mingle. In Singapore, SOC facilities have become hugely influential and multifunctional, offering comprehensive public services in one place. Under the incumbent administration in Korea, investment in the SOCs has grown, leading in recent years it to becoming more multilayered rather than independent.

Kim: In this context, we regarded Sinnae 4 District as a kind of city. The Sinnae transportation hub will be built near the site, while the existing Sinnae Train Depot will gain programmes to boost the city’s high-tech industry. On the eastern reaches of the site, there is a neglected outdoor sports facility – it was thought necessary to adapt a city-scale approach to accommodate these programmes, and to come up with a three-dimensional walking system that would weave between them with efficiency.

SPACE: Your project seems to address prescient issues boldly and squarely.

Kim: ‘Connection City’ is based on the idea of restoring an urban structure which is disconnected by the expressway. Other participants suggested similar ideas, but we were more daring in our efforts to create a large ‘artificial terrain’ connecting the green areas, creating an ecological forest in which the residents can socialise. When layers are formed multi-dimensionally by the topography and artificial land, and the aforementioned pedestrian walkway is constructed, the spaces under and around the structure will emerge. Life-enhancing SOC facilities, high-tech industrial facilities and facilities that make up self-sufficiency city will command the space.

It was important to be alert to technical issues in these plans. In conventional approaches, a road tunnel cannot bear building loads and, as such, the structure must be reinforced while compromising on the number of lanes on the expressway. Additionally, the isolation of vibration had to be adapted to the tunnel structure. We have the know-how to design a vibrationisolation system, but considering the cost issue, it was wise to separate a new structure for residential buildings from the road tunnel. In addition, a steel modular system was introduced. It could lower the building load about 40% in comparison with the RC. Fortunately, we have a great deal of experience in conducting various modular architecture projects. The plan could be realised thanks to our technical expertise.

SPACE: Units have been specifically proposed in accordance with the lifestyles of the residents. Although the guidelines called for 3 types, your consortium has come up with 9 types.

Kim: There are 5 types for single households depending on the functions such as storage and personal work space, etc. For couples with no children a type which focuses on the expansion of the space is proposed; for couples with children, on the other hand, a doubledecker house is more appropriate. Each unit was given a special feature. Our motto was to create a community where once you join, you would not want to leave: your children can live here happily for nearly 10 years until they enter elementary school.

Seo: Only one or two lifestyle types are proposed in conventional public housing projects because of the construction convenience and the cost control. The diverse needs of individuals must be considered carefully, but they are not. The neglect of desire sometimes makes residents leave public housing. We tried to include as much diversity as possible, and dreamed of a self-sufficient city, where one could stay for extended periods of their lives.

SPACE: The residential buildings of the total six were designed in pairs. I wonder what the purpose was, and why the two sides look out the same side?

Kim: First of all, if you look at the overall layout, there is a community space laid at the foundation that touches the ground and at the core of each building. The core can be used by the residents and the facilities below the foundations can be used by residents and neighbours, gathering and using the space together. The slope has become a rooftop garden. There is a vertical and horizontal flow of movement, but rather than breaking it, the sides are combined. It creates spaces that connect buildings, and puts small communal facilities around the core where it is close to the ground, so that a community could naturally form in the middle. A protruding pocket space or bridge connecting the two was also considered to make a place in which a functioning community, rather than dead space, could form by securing more than the standard amount of space.

Seo: It is a matter of choice to weigh which is the priority: privacy or communication. We tried to suggest a place which could protect the sentiments of the neighbourhood, like a small village, rather than those typical high-class dwellings that emphasise security.

SPACE: The plan should include facilities for the self-sufficient city in this competition. In order to support its functions, should it should consider the scale, purpose and operations of the facilities?

Kim: In the plan, we proposed several functions – within the category of selfsufficient facilities – that could support the high-tech industrial zones in the southern part of the Sinnae 4 District. They include dormitories for start-up employees, government-related agencies, and so on. The part where a ‘self-sufficient city’ was planned is the area to be developed in phase 2, as indicated by dotted lines on the site plan. We believe that this area will have a floor space ratio of 400%, similar to that of a semi-residential area. They may build high-rise buildings, but we designed the space to fit with the terrain.

SPACE: Now the plan needs to be implemented. What are the most important issues for the near future?

Kim: I hope that at least three aspects are retained. The first is the strategy of combining the two buildings to form a community. Second, we anticipate problems in the course of bridging the areas such as Myeonmok Station, transit center, and high-tech facilities, in terms of urban planning codes: I hope this part works out well. And finally, we hope that it will be completed without any structural dilemmas by developing the technology level to build up modular housing.

Seo: If our plan successfully creates a new city type and paradigm, everybody will want to live here. While the design and construction parts are important, certain functions must also be put in place for the actual residents, and certain programmes should be introduced within the SOC part organically, fulfilling its purpose by itself as a city. Should this not be an issue we all ponder together and make an effort to resolve in light of our bright future?

Shin Changhoon graduated in architectural engineering from Yeungnam University. He has trained at Artech architects, Baum architects and Himma architects. He established Unsangdong Architects with Jang Yoon-gyoo to pursue experimental and conceptual architecture. They are working on various experimental architecture projects such as Paik Nam June Memorial Hall, Gwangju Biennale Square competition, KT&G complex Center and the University of Seoul Lecture Hall.

Kim Deaone graduated from the school of architecture at Pusan National University and has practiced in POSCO A&C. He is now the chief architect of POSCO A&C. His involvement includes large-scale structural buildings based on his great interest in the largescale structure of steel, later on residential design and composite cities development. His focus is now on a brand-new means of urban regeneration. Major works include the Jeonju World Cup Stadium, KTX Shin Gyeongju Station, Samseong-dong Hyundai HILLSTATE, Jamsil PARKRIO, POSCO E&C Tower, and Tongyeong CAMP MARE.

Seo Hyoungjoo graduated from Hongik University and practices at POSCO A&C. His major works mainly focus on zero energy and eco-friendly architecture, such as POSCO R&D Center, POSCO Green Building, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Global Campus Dormitory 1 Green Remodeling.