As the world undoubtedly becomes more urban, it is increasingly difficult to discuss the project of the city in relationship to architecture. The city is no longer a definable physical form, but an endless

conurbation linked by infrastructures of cross-geopolitical boundaries. The term ‘city’ has become of a data-centric definition demarcated only by virtual boundaries for administrative and management purposes. The ‘megapolitan’ areas such as Seoul Capital Area, Greater Tokyo Area, Mexico DF, BosWash, Silicon Valley, agglomerate across administrative boundaries forming economic regions that hint at the ‘Ecumenopolis’ theorised by Constantinos Doxiades in the 1960s. Architecture in this scenario has been ostracized from the project of city-making, replaced by other fields such as urban planning and civil engineering, in a tradition established with the ‘La Sarraz Declaration’ at the CIAM of 1928. Yet, when observing the growth of a megalopolis such as Seoul, it is architecture alone that offers an understanding of the contemporary city and of how to read the new emergent typologies in urban organization.

Seoul offers a unique insight into the understanding of the megapolitan condition, through its typologies not only introduced by its rapid growth in the second half of the twentiethcentury but also by drastic changes in governance throughout its 625 year history, which has produced variants in typologies and urban fabrics that operate as urban islands. Studying the urban transformations that have occurred in Seoul over the centuries not only reveals the path-dependency that infrastructure has on city form, but more importantly, it shows a strong correlation between different levels of urbanity and how they produce corresponding architectural typologies.

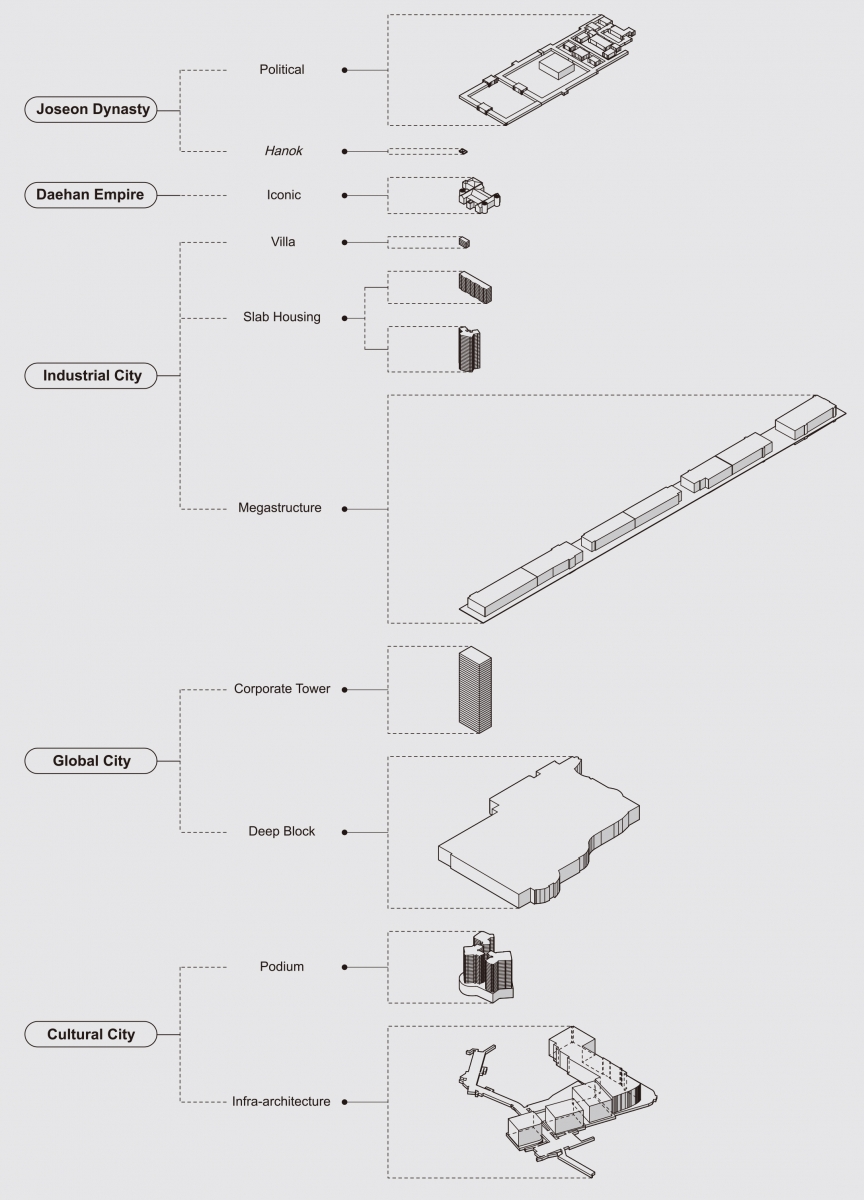

Seoul can be understood through ten dominant typologies, which appeared progressively from the foundation of Seoul in 1394 to the present-day megapolis. Each transitional phase of Seoul was directly linked to a different political and economic model, and a different density that has produced a diverse urban fabric with corresponding typologies that offer the basis for a typological urbanism reading of Seoul.

Architectural Typologies in Seoul in Chronological Order (ⓒRafael Luna)

Shortly after the foundation of the Joseon Dynasty in 1392, the new capital was built in 1394 as a new center for the kingdom. This city at its earliest point can be understood as a city of rituals. The infrastructural organization of the city followed the principles of geomancy and its architecture served the ritualistic operations of the king. This produced two typologies, the ‘Political Form’ as observed in the royal grounds, and the single-family ‘Hanok’ as the generic urban fabric that fills the compacted area inside the city walls constituting about 17,000 homes for about 100,000 people.

In 1897, King Gojong declared the formation of the Daehan Empire proclaiming the Gwangmu Reforms in order to open the isolated state to Western modernity. As foreign economic treaties were signed, a new architectural typology was introduced; the ‘Iconic Form’. These were Western Style buildings, separate from the more generic urban fabric, as stand-alone autonomous buildings that served as symbols of their progressive modern outlook. This typology produced a sparser sense of urbanity in a city that now reached a population of about 200,000 people. The population inside the city wall remained constant, forcing the city to spread beyond the confinement of the fortress wall as the Hanok typology could not withstand the increase in density.

The expansion of the city continued during the Japanese forceful occupation. This period starting in 1910 looked to continue the modernization reforms using the Meiji Restorations done in Tokyo and Osaka as a model for the colonial capital. The typology of iconic form was used as a tool in a process of assimilation in recognition of the Japanese Empire. Their presence symbolized control over the colony and, these forms were constructed following a wave of slum clearing projects in order to modernize the city with new infrastructures. The Old City Hall building, built in 1925 in an Imperial Crown Style, is an example of this typology that exists to today. Its typological autonomy produced a void in the urban fabric which persisted until it was transformed into Seoul Metropolitan Library. The independence of Korea after the fall of the Japanese Empire was quickly followed by the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, which left Seoul in an impoverished and devastated state. After the armistice of 1953, the immigration from rural to urban areas surged at a rapid rate, creating unplanned squatter settlements. Park Chunghee assumed power in 1963 and shifted the country’s economic focus to export-oriented industrialization, producing rapid economic growth. With the 1960s policies of heavy industrialization, immigration flourished at a rate of 300,000 people per year by the 1970s. The need for mass housing quickly became a primary agenda that instigated three distinctive typologies: a generic fabric low and mid-rise infill box ‘Villa’, mid and high-rise single-use ‘Slab Housing’, and the ‘Megaform/Megastructure’. Slab housing began to dominate the urban scene due to a scale of development consisting of one-thousand to two-thousand units distributed in multiple slab buildings in the same parcel of land. A single building housing development competing on this scale produced megaforms and megastructures as mixed use models, such as the iconic Sewoon Sangga, Nagwon Sangga, and Yujin Sangga.

The 1988 Summer Olympic was a driving force in showcasing the city as a modern metropolis, introducing two more typologies, the ‘Corporate Tower’ and the ‘Deep Block’. Both served as symbols of capitalist modernization and globalization. The corporate towers first took over the central core as a strategy for redevelopment in urban slum clearing. Large corporations were given the rights to parcels of land in the center of the city on the condition of developing the infrastructure of the block for their corporate headquarters as towers. COEX was developed in 1979 as a convention and exhibition center, taking over a megablock in Gangnam to display a globalized Seoul that could host international commerce.

By the turn of the century, the rapid rate of urban development that had pushed the population to ten million in a city of 605km2, also pushed production outside of the city and generated housing blocks as mono-cultural islands within the large megalopolis. This phenomenon was quickly recognized and towards the end of the century a new sentiment was brewing, hoping to transform the city from the growing industrial city to a cultural capital. This had a profound effect in the way the city began to value its infrastructure, and building stock, which lead to two new typologies that explore the optimization of the use of the land by offering greater diversity. These are ‘Podium’ housing, and the emerging typology of ‘Infraarchitecture’. In an almost live version of Rem Koolhaas’s ‘The City of the Captive Globe’, this podium typology emerges in the 1990s and early 2000s as a new model for mixed-use. Each podium base represents an entire block that contains commercial retail and offices, while on top of the podium slab housing towers stand as independent pieces of architecture. The infra-architectural hybrid typology, on the other hand, emerges from the underground systems built in the 1970s consisting of subway tunnels, and underground pedestrian crosswalks. As the city expanded, these underground networks grew into programmable commercial areas, such as Myeongdong Underground Shopping District and Yeongdeungpo Underground Shopping District. As more than transportation infrastructure, it became a second layer for the city to operate through underground architecture (infra-architecture in its literal meaning). The development of this typology as part of the contemporary cultural space is evident in the recent two architectural competitions: International Design Competition for New Gwanghwamun Square and International Invited Design Competition for Gangnam Intermodal Transit Center.

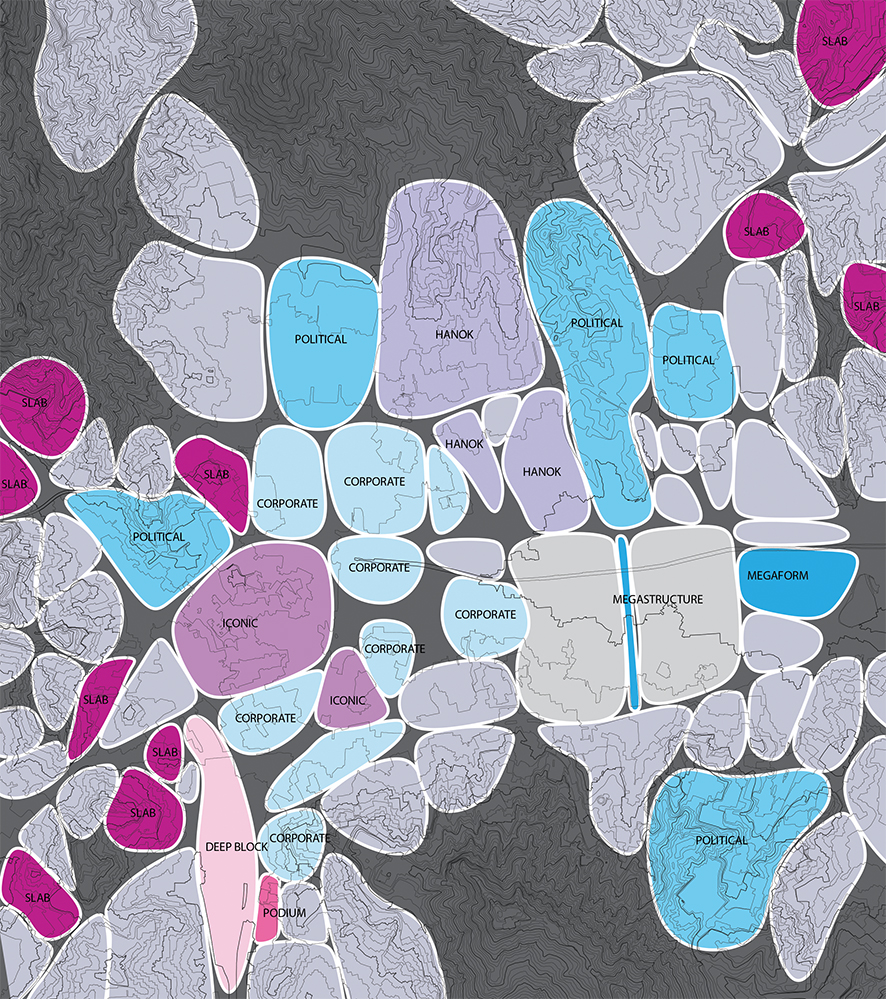

Each typology produces an urban effect that is distinct from the others, and by way of a generalization, these typologies tended to separate themselves from one another in urban blocks. Housing blocks are easily recognizable through their slab buildings, a Hanok village groups itself as a cultural enclave, corporate towers form financial districts, and so on. These different typological islands offer the possibility of analysis per island to generalize the conditions of use that would be repeated for the same typology on a different part of Seoul. For example, Hongdae offers the commercial appropriation of the space in-between buildings through the Villa typology. This typology repeated in another commercial zone of the city, such as Sinsa-dong, demonstrates similar appropriations of the in-between through micro-shops. This offers the possibility of mapping Seoul in a similar fashion to Patrick Abercrombie’s ‘Potato Plan’ of London, but through the demarcation of typological zones rather than activity zones as there is already an understanding of what type of activities the typologies allow to be in effect. This facilitates the possibility of comprehending and managing a large megalopolis like Seoul through the commonalities produced by each typology.

Seoul Potato Plan (ⓒRafael Luna)

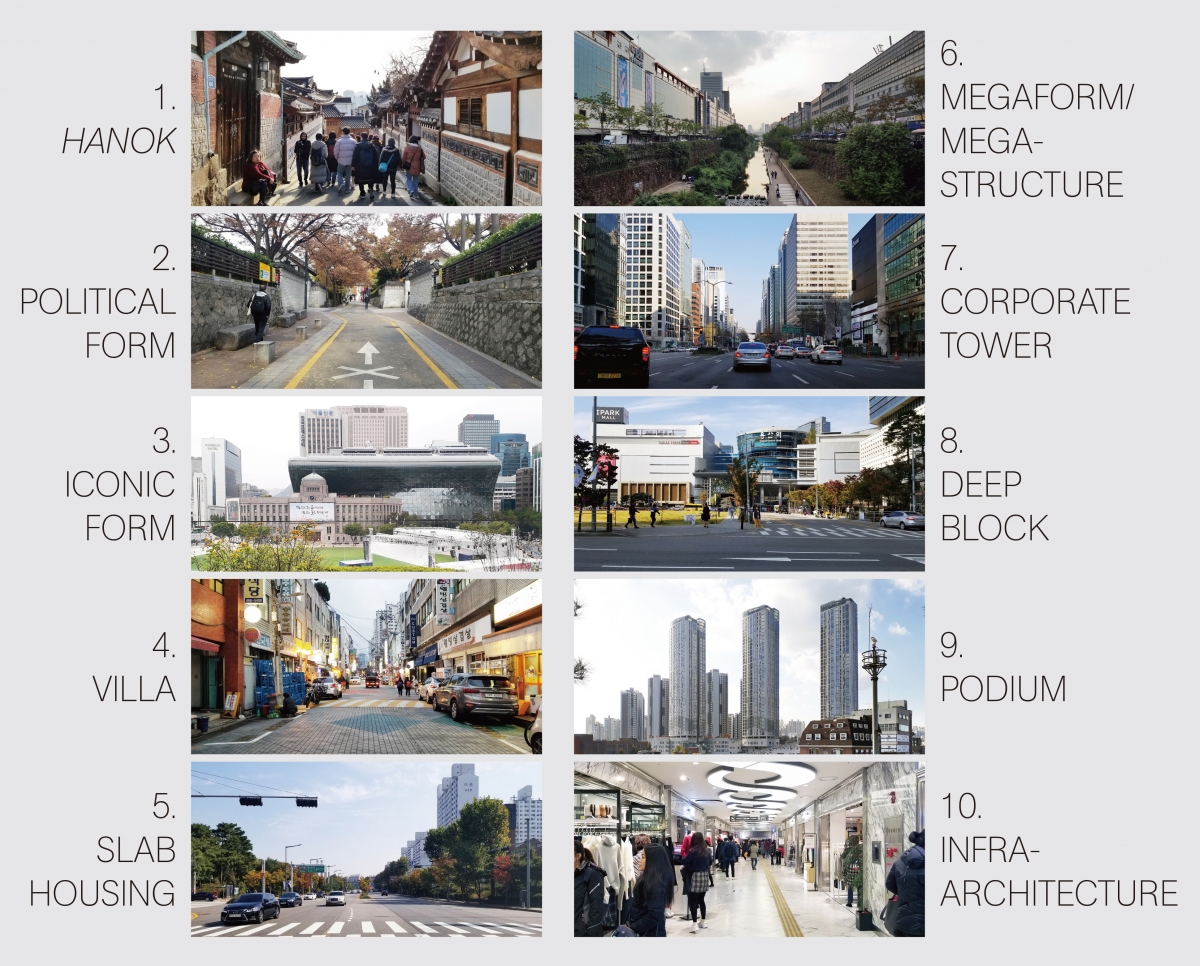

10 Architectural Typologies in Seoul (ⓒRafael Luna)

Definitions of Architectural Typologies in Seoul

1. Hanok, unlike that of the western single family suburban building, forms a high density low-rise urban carpet of a unified language. Its organic urban composition can be understood by what Maki Fumihiko describes as the ‘Group Form’.

2. Political form deals with politics on the ground. It forms an enclosure that separates itself from the rest of the urban fabric; for example, the walled royal palaces.

3. Iconic form is an autonomous landmark building, often forming a clearing in the urban sea.

4. Villa infills the fine grain modern fabric with a low to mid-rise, mix-use density.

5. Slab housing follows the modern orders of slab and columns in order to be reproduced quickly and efficiently.

6. Megaform and megastructure appear together and yet they describe different conditions. Megaforms are large horizontal urban forms that work within the existing infrastructure. Megastructures, on the other hand, feature horizontal urban scaffolding that produce their own infrastructure. They blend

infrastructural elements such as pedestrian decks, or vehicular roads, with superficial elements such as housing and retail complexes in one form. In this vein, Kenneth Frampton defines megaforms as the ‘Urban Landscape’ while Maki Fumihiko defines megastructures as the ‘Large Frame’.

7. Corporate tower is a commercial mixed-use high rise that offers the vertical multiplication of a parcel of land. It symbolizes a capitalist order.

8. Deep block is a singular building that covers an entire city block in one shell. It is the epitome of what Rem Koolhaas describes as the condition of ‘Bigness’.

9. Podium could be understood as a vertical hybrid building composed of a podium that defines the urban fabric with a different typology, often a housing highrise, on top. It could theoretically be understood as Ludwig Hilberseimer’s ‘Vertical City’ or Rem Koolhaas’s ‘The City of the Captive Globe’.

10. Infra-architectural hybrid appears to blend infrastructure and architecture. In Seoul, it exists primarily underground as a hybrid form between the subway system and architectural public space, blurring the lines between public and private.