A video of processing images is screened over black curtains. High-resolution photos of flowers, animal statues, human faces, motions, all flow seamlessly, and then images at a lower resolution, of more simplified forms and contours, finally of only black and white pixels sequentially projected onto the screen. At the end, it doesn’t identify whether the imagery of mouth-blowing is human or goldfish or just white noise. The process finishes and restarts with a mechanical sound, without explanation—Behold These Glorious Times! (2017) explores ‘the way machines produce images to train machines’.

Equally Glorious Moments

Trevor Paglen has long investigated state-of-the-art surveillance systems created to observe humans, even from space beyond the atmosphere. To address these themes, he devised The Other Night Sky (2007), which tracks and captures the orbits of old satellites and abandoned spaceships, and Drone Vision (2010), which shows a world from the view of an unmanned aerial vehicle. After 2013, when Edward Snowden exposed the national scale of surveillance systems, Paglen began to introduce works such as 89 Landscapes (2015), which contain photographs and videos of facilities with restricted access to civilians including the US National Reconnaissance Office and the National Security Agency. His zoom-in and long range filming connote radiodetection telescopes, telecommunications facilities, leaving the trace of surveillance activities that invisibly shape an idyllic and tranquil landscape.

Following these works, which are categorised by the keywords ‘mass surveillance’ and ‘sense of space’, Paglen shifted his focus to ‘machine vision’, which might be the result of reflecting on the shift from human to non-human beings who collect and interpret information. In this regard, a question arises; how does the non-human see and interpret the world? To express this in the language of Paglen, ‘What is technology trying to achieve? And how do these technologies with vision of the world rebuild the world?’

The above-mentioned Behold These Glorious Times! is a remarkable work when seen a part of the flow of this inquiry and in this exhibition. The artist offers an experience as if we are watching the machine’s thinking process as he penetrates the machine; not just because of the black curtains and closed screening spaces, but also because of repeated images without credits and titles and no seating (unlike the other video works).

The speed at which images are processed in the video is geared towards a human’s dynamic visual acuity. Although individual images are identified, it is quite fast and difficult to grasp details. It gives no room in which to judge or empathise. As a result, the spectator is sucked into the process while being overwhelmed by the flow of images. In the process, the image is simplified with dots, lines, faces, black and white, whether someone is smiling, or a statue placed on a table. Subjective elements such as emotions, moods, and feelings emitted by images are naturally missing.

Therefore, the object that the machine wants to process seems not to be the image, but the emotion contained in it or the audience’s inclination to sympathise with the image. As such, the exclusion of the human, the indiscriminate equality that does not consider the hierarchy of human-animal-things, presents an eerie impression. Machine sounds sent out along with the video reinforce this impression. Machine sounds flow out of the black box where the work is installed to form the background sound of the gallery. Therefore, when we appreciate other works, we are conscious of the space in which these emerge.

Seeing Machines and Seeing Behind Them

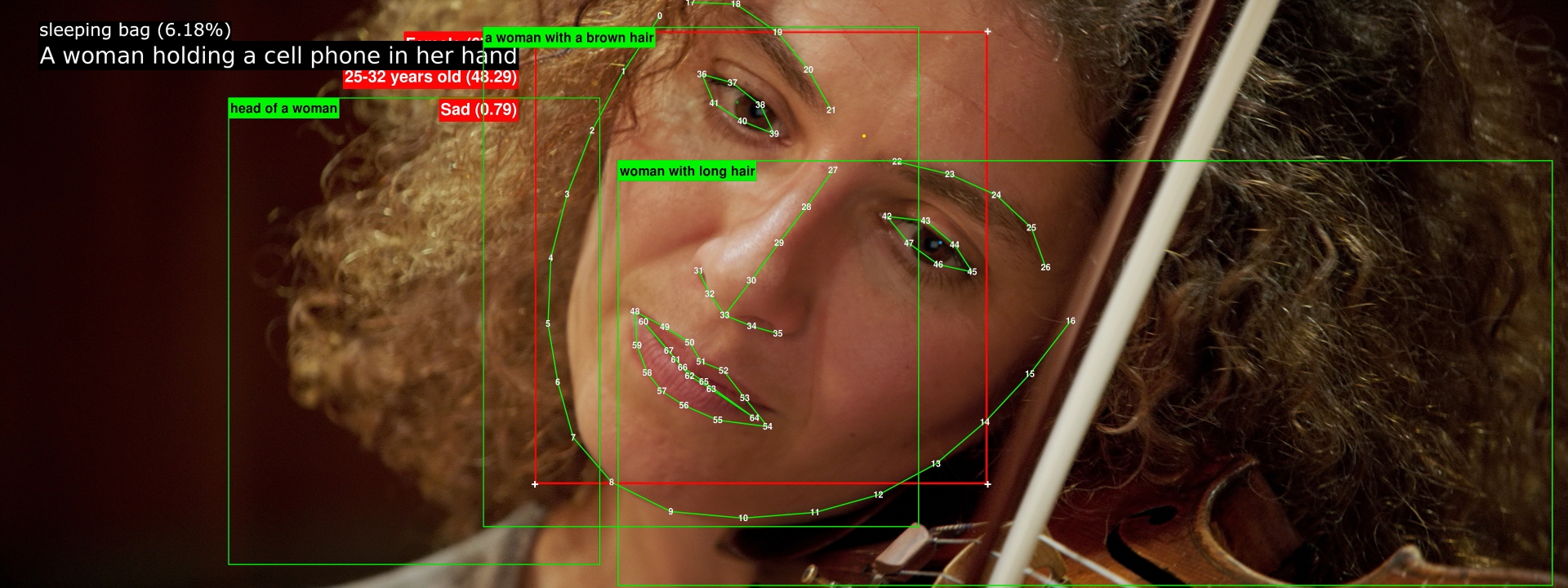

The single-channel colour video Image Operations. Op.10 (2018) goes one step further to question the social meaning of machine vision. On the video of the Kronos Quartet playing Claude Debussy’s String Quartet in G minor op. 10, the machine analyses the performers via algorithms and the resulting values are overlayed. For example, a high-resolution image that seems to be set by human gaze emerges, and then the image is transformed into black and white and monochrome images as if artificial intelligence is involved, and then the figures and patterns that appear to connect the contours of the face are added to the performers’ faces. Then, machine-generated information, such as age, emotional response, and gender of the performers, appears on the screen.

The analysis value changes from time to time. Some performers are estimated to be between 5 and 8 years old, while females are analysed as males. The result is continuously changing and corrected, adjusted, and recalibrated. Seeing this constant analysis and judgment, the question arises over what is behind the obsessions that sustain this behaviour. Why does it read like this and for what purpose? What is the process of simplifying a scene in which classical music is played, perhaps filled with emotions and energy, with flat figures and images?

The artist does not give a direct answer here. However, if one thinks of the phenomena that appear in society, this technology may already be applied to a biometric system that unlocks smartphones, a system that detects pedestrians who are autonomous cars, and a surveillance system that identifies the identity of anti-government personnel and captures actions, to change your daily life. Situations to promote convenience in life and to strengthen national surveillance are taking shape. An understanding of the system in which machines see things leads to questions about the society that creates the system. As the artist said, it is because ‘images have meaning only when we give them something’, and ‘in the new world, the question remains: what values, politics, and biases should be programmed into machines that look at images?’

Paglen finds clues in the specific events that have impressed him, exploring the conditions under which the case took place through years of research, and approaching the underlying structure. The photos and videos he presents make us think about the other side, though it seems simple at first glance. The exhibition is on until the 2nd of February, 2020.

(top) Trevor Paglen, They Watch the Moon, C–Print, 91.44×121.92cm, 2010

(upper image) Trevor Paglen, Image Operations. Op.10, Single channel 4K UHD color video projection, 5.0 Dolby Surround Sound, 23min, 2018