“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.”

“How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice.

“You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here.”

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland, 1865

Suh Jaewon and Lee Euihaing don’t make it easy for us. Every step along the way towards rationalising what they are doing, they set traps and diversions in our path. The biggest trap, right up front, is the obvious question their work conjures: ‘Why do they in 2019 still design such postmodern looking buildings?’ And we have to realise that we can only ask such a question if we ourselves are deeply immersed in the postmodernist paradigm; only a postmodernist is concerned about representation and appearance. ‘Are their buildings “ducks” or “decorated sheds”? Do they explicitly reenact a generic Korean multi-family house or do they decorate a multi-family house with an iconography that denotes its purpose within the Korean context?’; ‘Are they being ironic or even sarcastic, or do they actually believe in the language that they use?’ And now an unease begins to creep in: maybe if we try to find an answer to these questions we will come to realise that it is either none of the above or everything at the same time.

Buildings that raise so many questions cannot be explained through a simple building analysis, and always hint to a larger theoretical background. Once a building is set on a critical relationship with issues beyond its scope it withdraws itself from the possibility of being critiqued directly. It is never ‘as it is’ but just one piece of a puzzle that only makes sense if one considers the mind that conceived of it.

Suh Jaewon and Lee Euihaing set out their thinking in a series of texts that illustrate a very unique understanding of the Korean context. They point to rapid modernisation, unpredictability and fragmentation, heterogeneity, the crossbred full of irony generated by the success and harm of capitalism, the kitsch and the surreal, all of which comes to a surprising conclusion: to accept Korean reality as it is and to search for a possibility of including the contemporary Korean context in the architectural language. Thereby architecture is seen as a critical tool through which to reflect reality rather than as a tool to improve reality. It takes a stand against the almost pathological optimism of architects; the delusion that we can solve every problem of society through architecture. It shifts architecture from solution to critique.

‘So, they are building critique?’; and again none of the above and everything at the same time. Derived from the complexity of the Korean socio-cultural and socio-political context they build complexity: the complexity of meaning, complexity of contradictions, complexity of interpretation; architecture not as a fixed state of work in itself, but opened up and assembled by a multitude of factors, critique being one of them. They use ‘critical acceptance’, combining acknowledgement and criticality. This dual attitude, which we experience in everyday life, is fundamental but most often ignored in the architectural discourse. Through duality we can think about complex psychic dimensions inherent in everyday life. We cannot just rationally think of, or create distance between, what is going on around us. At every point we are immersed in our environment, we are part of it and have to use this fact rather than trying to escape it.

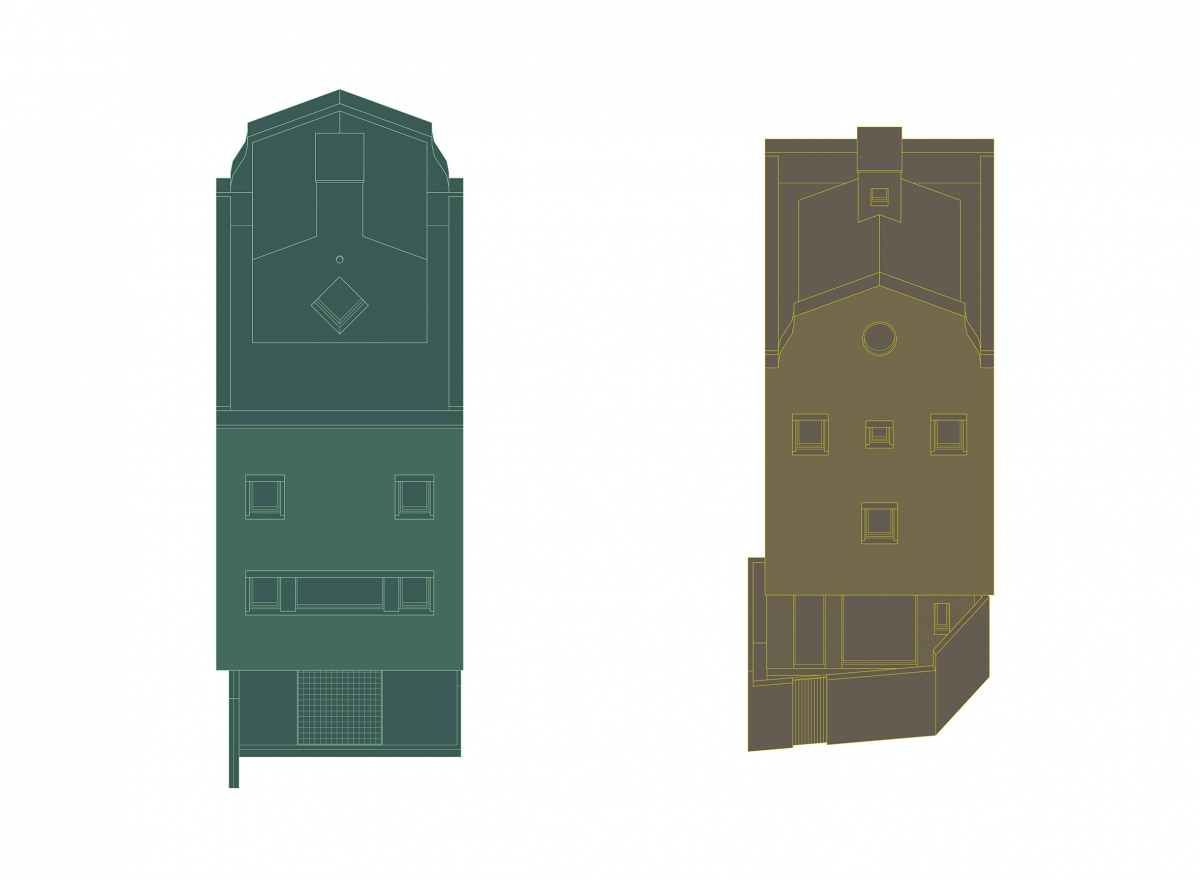

Malefemale House

This notion can be read most clearly in the Malefemale House in Hongeun-dong, Seoul. At first sight it is a neat looking single family house in a quiet residential area for a young couple without children. Suh Jaewon and Lee Euihaing reflect the clients in a ‘female’ front façade and a ‘male’ back façade, referencing the changing genderrelations of contemporary society, giving each person a distinct representation. At the same time they contradict the display of difference with a radical floor plan of equality and unification. The entire house is one vertical room, without a corridor, without privacy, without hierarchy. The space continuously flows from the first to the fourth floor. To reach a specific function one inevitably has to pass the spouse, interact, ‘communicate’, even if one of them is asleep. Difference, individuality, equality, togetherness, sharing life in all its contradictions are overlapped and expressed simultaneously. The ability to charge such a small building with such complexity of meaning while also appearing so simple is a unique achievement that can be only attained through critical acceptance rather than through providing solutions. A ‘solution’ entails simplification; it is the editing and reduction of possibilities, while critical acceptance opens up a multitude of simultaneously overlapping possibilities.

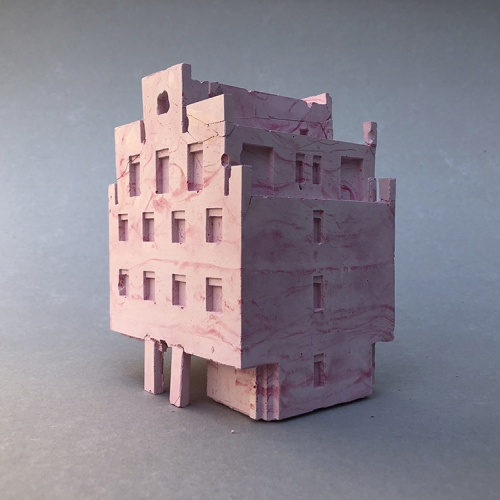

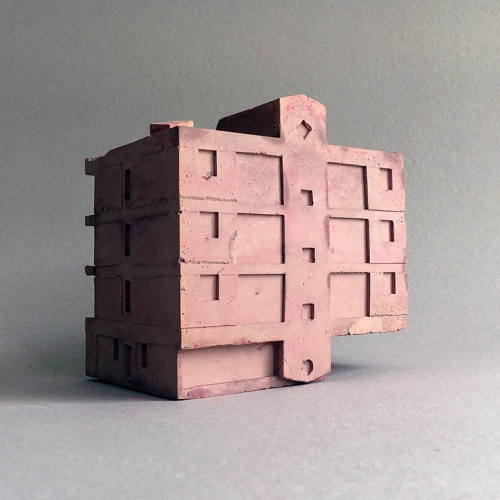

The Cascade House in Mangwon-dong, Seoul, is similarly radical. Again it appears like an almost generic Korean multifamily house, elevated above the first floor for car parking and with a monotonous punctuated façade; referencing maxed-out-for-profit investment buildings. But then they contradict and deconstruct this notion: the exquisite materiality of the hairline fracture red tiling, which gives depth to the flat façade; the hidden entrance with a heavy tiled door, blurring it with the exterior wall, giving the immediate feeling of privacy and protection from the chaos outside once it closes behind you. The floor plan of the units itself is a prime example of how to create the maximum quality within a limited space: the careful arrangement of the side-functions bundled together, overlapping at the same time with the main spaces and thereby extending the spatial experience; the placement of windows in these overlapping spaces allow light to penetrate deep into the apartment; the extension of the bedroom through a glass block wall towards the kitchen; the absence of a suspended ceiling in the main living room combined with a differentiated materiality of large sliding doors and column in transition to kitchen and bedroom. All this makes the space flow; one never feels trapped inside the building. It is the antithesis to the claustrophobic interiors of the generic Seoul while still pretending to be just that—the question is not how different it is from the standard but the revelati on that the standard can have an amazing quality.

This precision of detail hints at a relentless effort to find beauty in the banal, to claim the relevance of the everyday in Seoul’s architecture. Looking at Suh’s and Lee’s design process is the clearest proof that they are not interested in irony or sarcasm. They refuse to play the Floor Area Ratio Game. They are not interested in making the ‘maximum’ look contemporary, but try to find the essential that is necessary for atask. Endless tests of floor plans were produced not to optimise the functions but to optimise the quality of functionality; endless façade drawings by hand to find the most adequate materiality and expression; large 1:20 models with detailed furnishing and traces of everyday life to look from inside out and not from outside in. With this relentless testing, architecture becomes process and not result, it becomes an equal part of our life and not an object that we look at or that contains us. To paraphrase Ad Reinhardt: Architecture will react to you if you react to it. You get from it what you bring to it. It will meet you halfway but not further. It is alive if you are. It represents something and so do you. You are a space too!

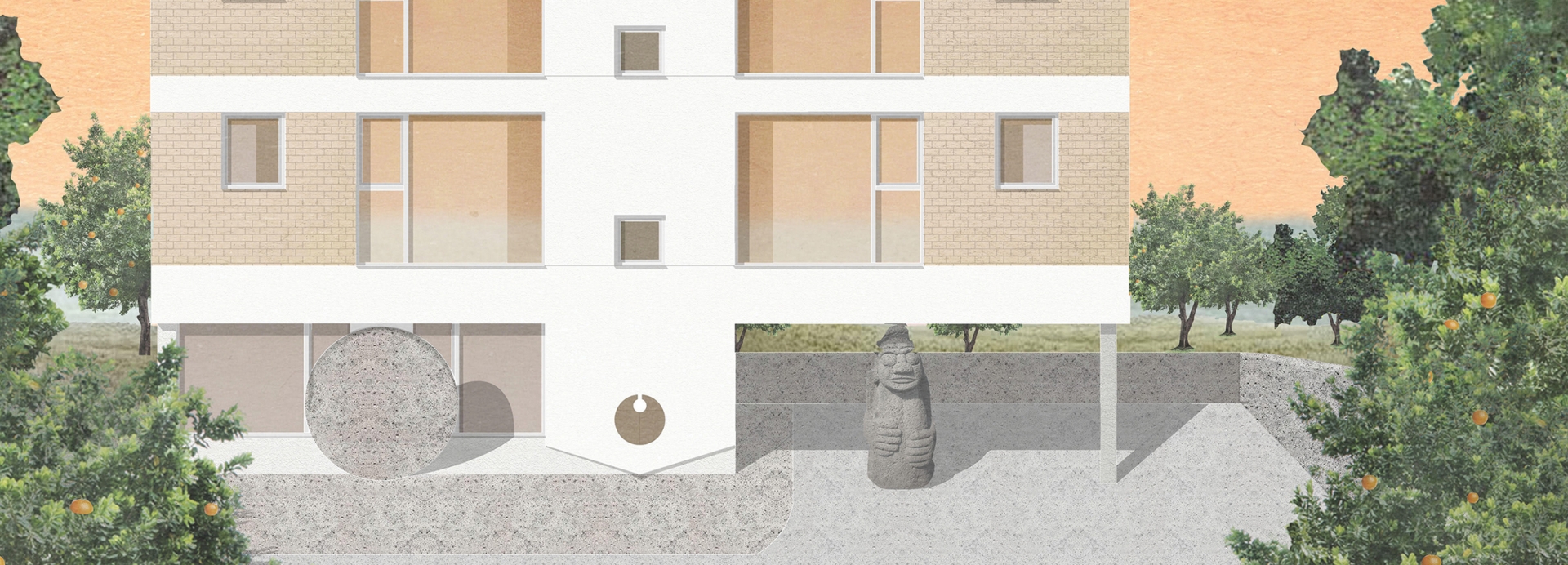

The Villa Jeju is probably the most difficult to decode. It brings us deep down the rabbit hole to meet the delusions architects have about ‘Korean-ness’. It is easily discarded as kitsch and ‘out of context’ which immediately raises the question, on what do we base this judgment? Architects love to talk about the traditional Korean relationship between architecture and nature, they try to distill a notion of Korean identity, which, if we are honest, either never existed or is constructed out of a romantic notion of a lost past. But there is no real ‘lost’ unless we dissect what the ‘lost’ means. There is an easy assumption about the loss of relations to nature while there actually is nothing such as nature. Nature is an intellectual construct that we might feel on a day-by-day or moment-by-moment basis, from the sense that we cannot simply assume a past ideal of nature and relationship to it. In all this is missing the attempt to understand and accept the contemporary banal, everyday aspects of the Korean city: to build up on what is there and not to introduce an assumption of the ‘lost’. The context of Jeju Island is neither one of nature nor of Korean-ness but of the banality of an environment formed over time and circumstance. The Villa Jeju does not try to evoke a fake relationship to nature but establishes a commentary on the current state of the Korean mentality and its mechanisms while introducing through the backdoor a quality of living that is absent in everything that this mentality and its mechanisms generate.

Villa Jeju

And there is one last issue raised by ‘problem-solving versus critical acceptance’: the self-conception of the architect. In the attempt to solve social and humanistic issues we generalise and objectify. We fall into the delusion that we act ethically because we strive for a higher goal. How do we design architecture for the Korean social and cultural context when a building doesn’t want to be anything, when it doesn’t want to relate to anything, when it doesn’t want to represent anything, or when a building essentially has no function, no economic life-span, no value to anyone else but to the immediate client? The architect in Seoul is put into an almost absurd situation, where the only reference point for his work is he himself: his unique value system, his ethics, and personal beliefs. They are the only criterion upon which his work can rely. As Suh Jaewon phrases it: ‘A building may be public but we have to accept that architecture is a very personal, deep and subjective expression of the architect as they develop new rules on their own.’

Suh Jaewon and Lee Euihaing’s architecture has to be seen as consciously subjective. It doesn’t try to be universal; it doesn’t try to be a template for others to follow the same strategy: it emphasises the architect as the sole author, with all of the consequences for society. Architecture has to be seen a personal process; it demands complexity of thinking, layering and fragmenting of meaning, and it needs to embrace critical acceptance to claim relevance in this society.