In 1857, a group of American designers founded the American Institute of Architects (AIA), the first professional organisation for architects in the United States. Women were not exactly excluded, but they were simply never considered. From its earliest beginnings, the architectural profession was inherently closed to women, in large part because of the educational system that groomed future practitioners for its ranks. By the late 19th century, American firms, run by famous architects, had become the ultimate ‘old boys clubs’. A few extraordinary women were able to gain apprenticeships, but most were denied access to professional offices and the valuable networks they represented. The hierarchy within the office, the arbitrary nature of promotion, and the necessity to attract clients were among many unspoken barriers that limited the success of women in the profession.

A few aspiring female practitioners did manage to infiltrate the studios of late 19th century architectural firms, but women did not enter the profession in any significant number until they were allowed to earn college degrees. During the late 1870s, two coeducational land grant colleges admitted women into architectural programmes. In 1878, Mary L. Page became the first woman to attempt this route and train alongside male students. She received a certificate in architecture from the University of Illinois in 1878 and a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree in 1879. Margaret Hicks, who earned her Bachelor of Architecture at Cornell in 1878, graduated with a BS from the university in 1880.

When Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) opened its architectural programme to women in 1885, it soon became the most attractive option for female students eager to gain a rigorous design education. The first to enroll, Anne Graham Rockfellow, graduated from the two-year architectural programme in 1887. By the turn of the century, twelve women had graduated from the prestigious school, the first school of architecture in America.▼1 In the early 20th century, pioneering women architects were beginning to hire the next generation of college graduates and were gradually forming networks between themselves and in close association with female patrons. The architect Julia Morgan, the first woman to graduate from the École nationale superieure des Beaux-Arts, opened her own practice in 1904, and by 1927 her staff of fourteen included six women. Ida Annah Ryan and Florence Luscomb, classmates at MIT, opened a firm in 1907. The office of Lois Howe and Eleanor Manning was founded in 1913 and would later include fellow MIT alumna Mary Almy, hired in 1926.

The first school devoted exclusively to educating women architects and landscape architects ‒ the Cambridge School of Domestic Architecture and Landscape Architecture ‒ evolved from a continued interest in the subject and the effort of dedicated Harvard professors. In 1915, Radcliffe student Katherine Brooks sought admission to the Harvard School of Landscape Architecture, and when she was denied instruction, a professor offered to teach her in her home. Just a few months later, Henry Atherton Frost was tutoring Brooks and five other women in his Cambridge office. Word of the new programme spread quickly, and by the 1916 ‒ 17 academic year, announcements were sent out advertising a formal course of study. The Cambridge School students benefitted from instruction equivalent to that of their male peers at Harvard and exposure to the real business of architecture in Frost’s office, as well as the fellowship of other women striving to succeed under similar circumstances.

At the about the same time, a new type of organisation exclusively for female architects ‒ a group to support women as they struggled to gain a foothold in the profession ‒ was founded by Harriet Mae Steinmesch, a young architecture student who understood the challenges faced by her female peers. She and three of her classmates at the School of Architecture at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, founded a sorority, ‘La Confrérie Alongiv’ (the last word is Vignola spelled backwards). After Steinmesch graduated in 1916, she committed herself to creating a national sorority, and by 1922 had established Alpha Gamma, with chapters at the University of Texas, the University of Minnesota, and the University of California at Berkeley. In 1928, alumni drawn from these groups joined together to establish the Association for Women in Architecture (AWA). Steinmesch was one of the founders and the inaugural president of the AWA, the first professional organisation for women architects in the United States.

As the number of aspiring women architects increased, new groups were founded to support their endeavours. In the same year that Steinmesch launched La Confrérie Alongiv, women at the University of Michigan devised the T-Square Society. In 1921, Elisabeth Martini established the Chicago Drafting Club, which seven years later had grown to become the Women’s Architectural Club of Chicago. Two former members of the T-Square Society, Bertha Yerex Whitman and Juliet Peddle, were among the new club’s nine founding members. By this point, more than two hundred American women were practicing architects and eight were members of the AIA. Members were elected by their peers, and admittance was considered a stamp of approval in terms of education and excellence. The Women’s Architectural Club of Chicago was inspired by the 1927 Women’s World’s Fair, which featured architectural work and provided networking opportunities among colleagues. The club held exhibitions in the library and acted as the social hall of Perkins, Fellows and Hamilton, the architecture firm where both women were employed. In the 1940s, the group became part of the Chicago chapter of the AIA and was reduced in status to an organisation for members’ wives. During the 1970s, the women’s movement inspired female architects to challenge the continued prevalence of sexism and workplace discrimination inherent to their profession.

The remaining chapter of the AWA, located in Los Angeles, reorganised itself as the Association for Women in Architecture (AWA-LA), to include male members and women involved in other aspects of the profession. Dolores Hayden, an architecture student at Harvard, founded Women Architects, Landscape Architects and Planners (WALAP) in the early 1970s, with the aim of improving workplace conditions for female practitioners. At the same time, the New York based group Alliance of Women in Architecture (AWA), founded by Regi Goldberg, targeted the AIA for denying any cases of discrimination, not to mention for failing to improve conditions for female practitioners more broadly.▼2 The AWA prepared an ‘Underground Guide to New York Architects’ Offices’ to help women find secure employment. Open Design, an allwoman architectural office launched in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and invited female architects to ‘bring in their own projects (or work full or part-time on those brought by others)’. Goldberg and her colleagues planned to open another office, the non-profit Architectural Alternative, along similar lines.▼3

Inspired by the writings of AWA’s founding member and Architectural Forum editor Ellen Perry Berkeley’s efforts, a group of her peers founded the Organization of Women Architects (OWA) in the Bay Area region of California in 1973.▼4 As part of its mission to make its members more visible, the OWA exhibited a mural depicting fifty local women architects at that year’s AIA convention in San Francisco. The group developed other creative ways of supporting members, such as creating the ‘Mock’ exam to prepare prospective architects for the state licensing exam; the test preparation system was so successful that OWA later sold it to the AIA.

In addition to the activist organisations of the 1970s, organisations with corresponding missions were founded in subsequent decades. The architect Milka Bilznakov created a valuable resource for expanding knowledge of women in architecture in 1985, when she established the International Archive of Women in Architecture (IAWA). The IAWA provides an online data base on women architects, as well as an archival collection held by Virginia Tech University in Blacksburg, Virginia. The archive also offers grants in support of research on women in architecture. In 2003, the architect Beverley Willis launched the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation (BWAF), an organisation dedicated to promoting and supporting the work of women architects. The Foundation sponsors lectures, exhibitions, and other events to address the issues confronted by women architects and to spread awareness of their many contributions to the profession. One recent project, ‘Pioneering Women of American Architecture’, is an online archive with profiles of significant female architects of the 19th and early 20th centuriesy. Both the IAWA and the BWAF are dedicated to supporting architects by uncovering the forgotten history of their female predecessors.

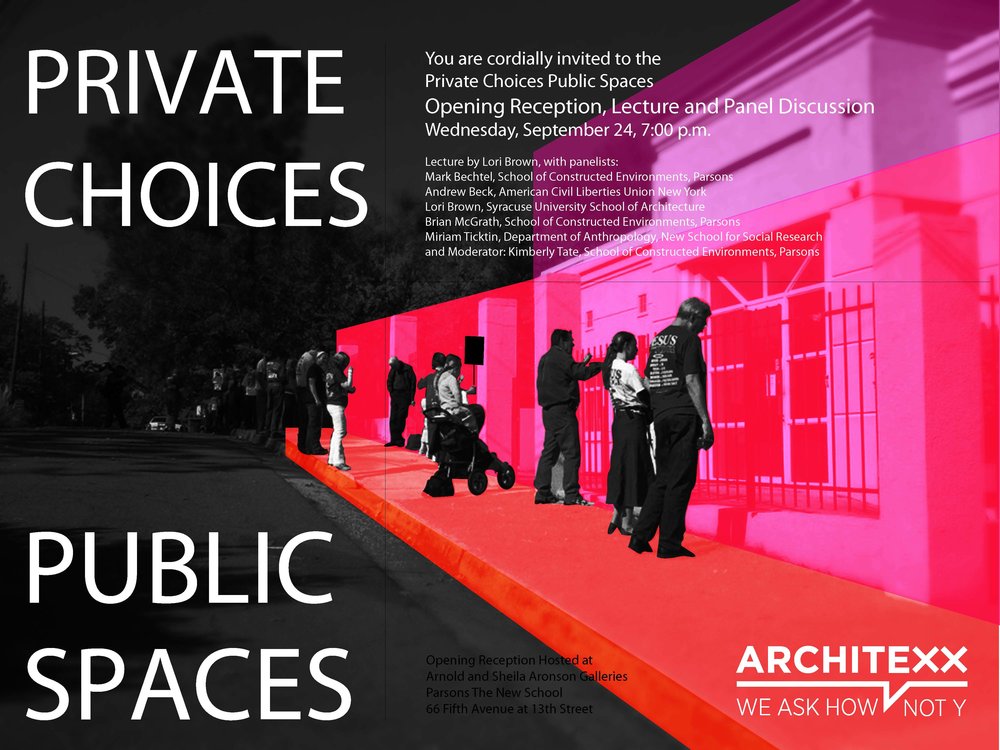

In 2013, Lori Brown and Nina Freedman founded ArchiteXX, a non-profit, independent organisation that aims to transform the discipline for women in architecture by bridging the academy and practice. In its effort to achieve gender equity, the group promotes leadership and retention of women in the profession, and to that end, facilitates open dialogue that will inspire the next generation to see themselves as agents of change. ArchiteXX creates opportunities for exposure, mentoring, and public engagement. Since its founding in 2013, the entirely volunteer-run nonprofit has produced a regular newsletter, online journal, monthly networking events in New York City, a lecture series in accredited schools of architecture throughout New York State, and various support groups. In addition to its ongoing initiatives, ArchiteXX has organised exhibitions that highlight timely issues. The first exhibition, ‘Private Choices, Public Spaces’ (2014), was displayed at the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center at Parsons School of Design in New York. ‘Now What?!’, ArchiteXX’s second exhibition project, originated in 2015. The planning, outreach, and travel tour of the exhibition throughout the United States has expanded the organiszation’s partnerships and organizational capacity.

For over a hundred years, American architects who happen to be women have found support and solidarity through organisations dedicated to furthering their opportunities in the field. Today, the global nature of the profession demands international networking, as women take on commissions and collaborations throughout the world.

‘Private Choices, Public Spaces’ poster, Image courtesy of ArchiteXX

-

1. Sarah Allaback, The First American Women Architects, University of Illinois Press, 2008.

2. Paul Goldberger, “Women Architects Building Influence in a Profession that is 98% Male”, New York Times, 18 May 1974.

3. Rita Reif, “Women Architects, Slow to Unite, Find They’re Catching Up with Male Peers”, New York Times, 26 Feb. 1973.

4. Inge S. Horton, “OWA at 40”, OWA+DP Forum Post, 23 Feb. 2013.