Practice

Architecture is the act of balancing an ideal with a reality. Some focus on the ideological aspects of their work, while others concentrate on the actual process of completion and the final result. Before I began working as an independent architect, I learned how to develop conceptual work and a critical voice at art college. After graduation, I gained practical experience in a large interior design firm in Korea. It did not take long to realise that a particular way of working, based upon ideas and concepts, did not suit me. It is very important for me to perceive what I like and what I can do well; my strengths are that I can decide on a course of action fairly quickly and that I never look back once my decision has been made. As such, I resolved to find a sense of balance between my intuition and the universal solution in the work. Certainly, this cannot be considered as the perfect interaction between opposing forces; but focusing only on solutions to actual problems may lead to a conventional outcome, while overly pursuing concepts may result in an architecture that differs from that outlined in the initial plans. We admire the great unbuilt proposals of the Paper Architects, but there is an enormous difference between the design of an architect who has completed an actual work and the proposal of an ‘architect who only works on the proposal’. When Louis Sullivan heard that his Schiller Theater Building, which he had designed, was about to be demolished, he responded, ‘it is not surprising to hear it. If I live longer, I may end up seeing all my buildings gone. What remains in the end is the concept’. This remark remains persuasive because Sullivan illustrates the former case; an architect’s writing is sufficient as an architectural outline or as documenting a simple episode, construction drawings are better than sketches or fancy graphics, and exhibitions or open houses are more pleasant as participation exercises than lectures. What Min Workshop considers most important is the process of developing architectural drawings and coordinating their application on the construction site.

Durastack Headquarters

Ways of Seeing

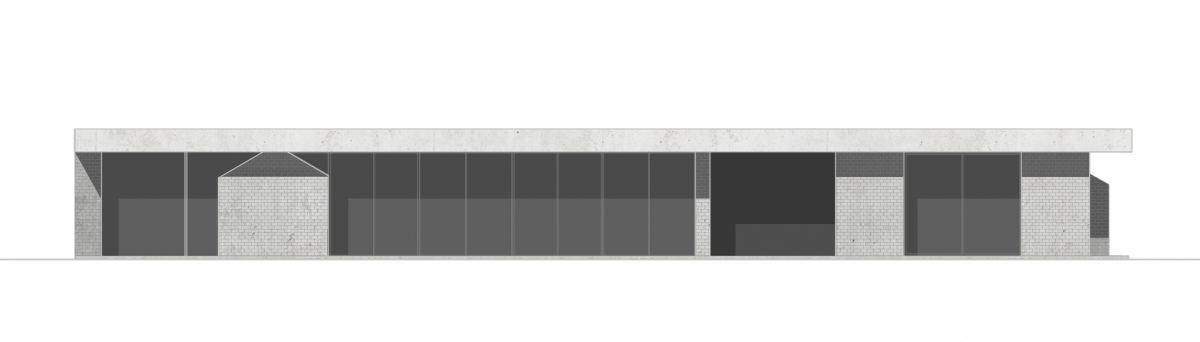

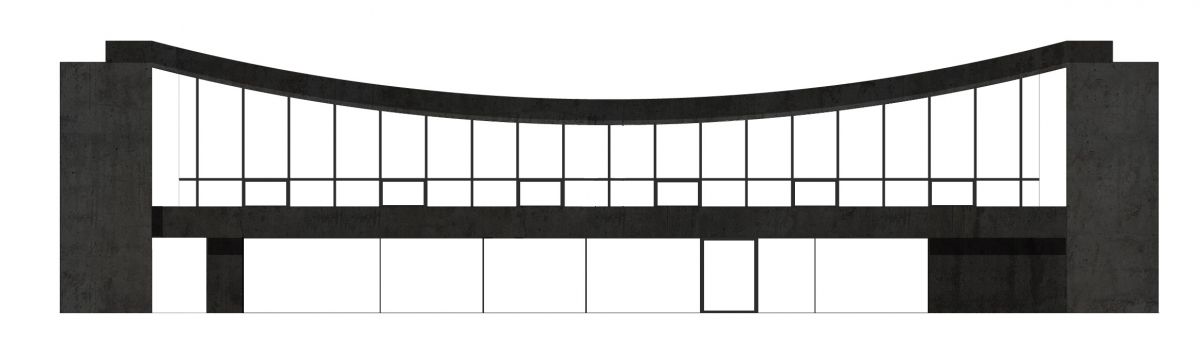

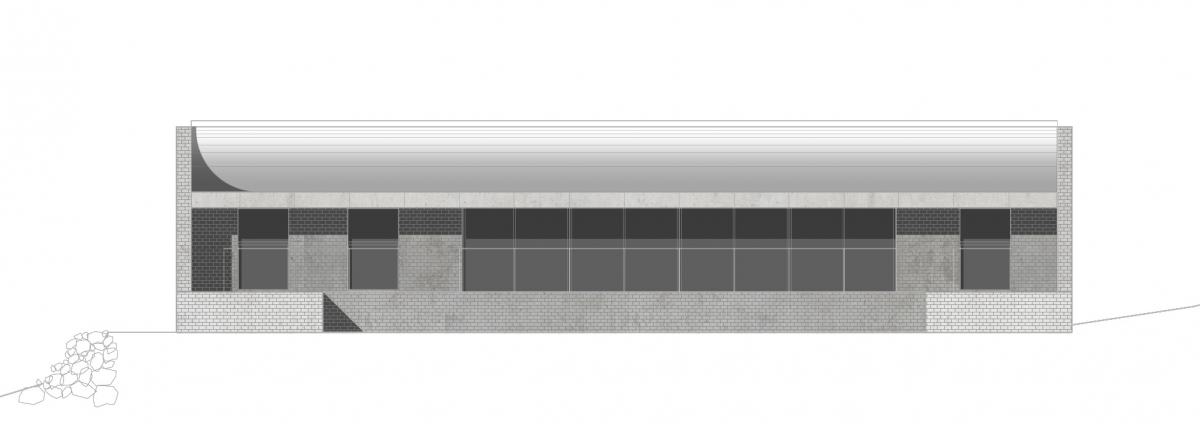

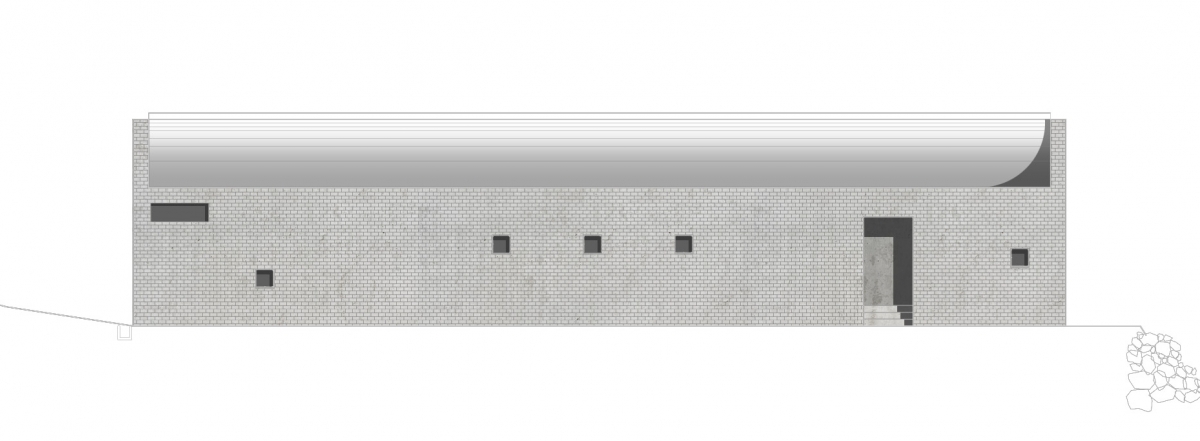

Nowadays, the level of finishing or technical completion has reached a certain level of expectation, and those who visit buildings often mention those details. This may be why ‘handicraft detail’, which did not receive much attention in architectural design of earlier decades, has risen to become an important issue for Korean architects. During my childhood, I grew up experiencing a lot of ‘well-made’, ‘sophisticated and wonderful things’ under my parents’ influence and by virtue of my father in particular, who is an architect, I was able to observe many brilliant details through him. I find this recent trend bewildering but pleasing, and yet I worry that it will end up as a phenomenon guided by the fear of being branded old-fashioned. Detail not only dictates how the joints are formed where the materials and parts meet each other, or how these joints should be finished. This is not an ability to put on a flamboyant performance, like vaunting technological prowess, but to freely handle the elements of architecture. There should be a set of principles when applying details: it is important to use details that are suited to each situation, highlighting architectural elements such as lines, faces, masses, and materials, or expressing them placidly. These principles enable designs to evolve from the microscale to macroscale. In Concave Lens (refer to SPACE, no. 571), an inevitable situation is described, in which a bump occurred on the partition wall of the first floor. Based on the decision to divide the wall into a segmented mass rather than maintaining the single mass with a bump, so as not to ruin the frame of the overall space, the wall was cut into parts and glass was inserted between them. It was not a detail that intentionally drew on other materials. To me, cutting the wall into different parts was a matter of detail itself, and the method of joining the glass and the wall was not a big issue. The most important details in Vault House are the door of the laundry room, which needs to be seen as a single mass, and the kitchen’s lightbox, which suggests that a steel structure has been inserted. In Durastack, a 25mm-gap was given at the point where the brick and the roof slab meet. At first, it may seem as if a brick mass is supporting a concrete roof, but in fact, this is a detail –a trick to show that there is a concrete bearing wall in the interior. The most important detail in Café TONN is the way the heavy exterior columns meet the inverse beams of the roof. Each of the roof slabs, large columns, and inverse beams reveal their form, and in order to reveal their assembly, the method of joining reinforced steel has been reconfigured. The details that attend to every corner and that correspond with the governing context of architecture are more significant than the admirably skillful techniques and costly and fancy details.

Cafe TONN

Natural Light / Architectural Lighting

Which architect places less significance on natural light? It is very difficult to deal with natural light and architectural lighting at the same time. When I bring light into space, I like to make the source of this lighting unclear. In Odd Corner (2012), I used a technique that would draw natural light through a gap between the divided building mass, instead of using a typical window made by puncturing the exterior wall. In Concave Lens, a double wall was installed, and the scattered light between the openings of the wall and the skylights above them was brought inside. At first, people think of the light coming from the opening of the curved wall on the second floor as architectural lighting, but as time passes, the light’s texture and direction change and people realise, ‘Oh! That is actually natural light’. The window’s shape and size is important, but its position inside the space is far more significant. In Vault House, a low window on the first floor only 45cm above the floor and a 24m-long thin skylight were devised, subtly cutting through and enlarging the space. When dealing with light, daytime and night should have the same hierarchical position. Lately, I have noticed a tendency to shun the ceiling light in Korean buildings. In Western houses, the spaces look much more sophisticated as no direct light is installed in the ceilings, except in the kitchen and the bathroom for more functional needs. However, it is difficult to do this in Korea due to the fixed lifestyle and cultural differences. Therefore, I used different kinds of architectural lighting, such as indirect lights, direct lights, luminous ceilings, and line lights, and separated their circuits to provide a varied ambiance. It sounds conventional, but in fact, this is an elaborate and sophisticated architectural technique. Even for architectural lighting it is good to use the indirect method, so as not to expose the position of the light source and to enable adjustment of the colour and brightness in order to contrast with natural light. In the case of Café TONN, the first floor is relatively dark during the daytime due to the eaves, and the second floor is always bright by virtue of the glass wall running on all directions. At night, the first floor is very bright due to the direct lights, and the second floor is dark and soft due to the indirect lights. It is always pleasing to use light to reverse time, changing the day and night of a building.

Vault House

Form Making

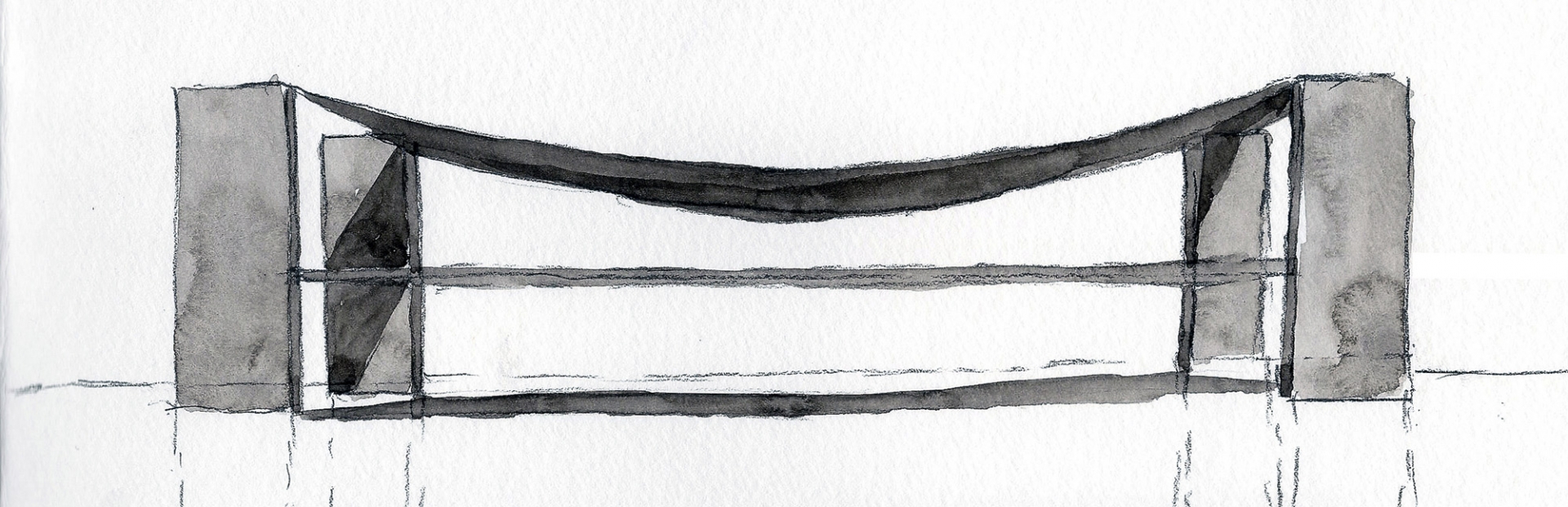

Along with colour, form is the fastest and the most definite way through which to recognise objects. The form is a necessary and sufficient condition for creating space, and it is a fundamental element of architecture that must be given priority over anything else. However, the act of clinging to a form may be perceived as that of a less mature architect, and since people either like or dislike to the extreme a form based on their subjective views, architects tend to become passive in dealing with form. Ever since I was young, I had been interested in modeling, and so I have consistently focused on it as a central concern. In the earlier days of my work, the pieces were twisted, cut, or added to, to create new forms as if they were sculptures. In recent years, I have been focusing on the scale, proportion, and composition of the basic architectural elements such as floors, walls, columns, and roofs. This method distinguishes it from more exaggerated and colourful forms. In the unbuilt Daejeon project, I conceived of a different scale for the columns and used tricks to connect them vertically. A sense of dynamism and tension are expressed in the appearance of these columns, shifting from the upper level’s columns that are heavier than required to the lower level’s several thin, tilted, and in fact, properly sized, ones. This is not something new: Mies van der Rohe already used this technique to manipulate the purity of a structure in many of his works. Therefore, there is still a lot of potential for primitive elements and compositional methods in architecture. Durastack appears as if heavy masses support the thin roof, but each of these large masses are hollow inside, serving as a ‘room’ to accommodate their programmes. There are many elements of architectural deception, as mentioned above, spread throughout Café TONN. At first, people pay attention to the form of a concave roof, but when they look closer, they realise that the four massive exterior columns serve as important design elements. A closer look reveals that the four large columns are ‘excessive structures’ that only support the roof, and the floor slab of the second floor almost touches the edge of the column, disclosing the fact that it is not structurally related to the columns. However, these excessive columns are not even the ‘main structure’ that support the roof: most of the actual load is handled by the 52 window frames made of metal. This description may make one think that steel columns are required as it is a heavy concrete roof, but the weight can actually be managed by half of the current number of columns. A couple of moments of foreshadowing hide the true structural method, and the composition of exaggerated or reduced architectural elements create a space of strange tension.

Some say architecture is a work of anchoring to the ground, others that it is a boundary line between ideas, and others a phenomenon that the body perceives. An influential figure of his time states that architecture is surfing, as it has to balance on the waves of its governing capital and programme. Likewise, many attempts have been made to define one field, a natural compulsion that results from living in an age where trends rapidly change and surge. I think architects have the space to return to the oast and explore architecture itself. The term ‘architecture of architecture’ is the slogan of a team of fellow architects that I often meet at a gathering. The design nuances that they employ are a little bit different from my own, but this phrase somehow holds my attention. Certainly, architecture needs to consider the relationship with the land and create harmony with its surroundings, needs to meet its function as a building and propose new programmes and lifestyles. However, my priority is a bit different. Regardless of the many various conditions that inform architecture, architecture’s values of existence can be expressed through the basic elements that support architecture, such as materials, forms, structures, and light. I believe that a building can be made to be like a work of furniture, with lots of good uses. Just as there is a chair that fits in any environment, and a table that shows its true quality in a specific place, should there not be an architect who strives to produce a well-made product? Recently, Min Workshop has undergone some changes in its approach to the work’s purpose and scale, and now begins to have an interest in materialising architecture of a more primitive style: a simple, clear and open space that is not divided by partitions; a form that is easy and intuitive, informed by the use of a single material; architectural deception that exposes and hides the framework of structure and space; expressing the genuine existence of architecture regardless of its purpose for use. I believe that these architectural attempts could develop an architecture that will be far better remembered and experienced.