Barbara Kruger, a text-based artist, has long worked with the reassembly of words derived from mass media contexts, drawing out her own messages from this material. In the early years of her career, her works juxtaposed images and text and received widespread attention. Since the mid-1990s, her radius of activity expanded to include site-specific installations and video works. Some years ago, she claimed in an interview that ‘what the media have done today is make a thing meaningless through its accessibility. And what I’m interested in is taking that accessibility and making meaning’.▼1 As she here suggests, her interest in harnessing media utterance and using it in her workhas always been understood in the context of the artist’s career. After going to Parsons School of Design in New York in 1965, she landed a job as a designer at a magazine, overseeing and editing photos for about ten years, acquiring the expression techniques of mass media—all of which became the basis for creating her unique style.

‘Kruger Style’ and Advertising Techniques

Beginning work in 1969, her distinct style – combining blackand-white images, red rectangular frames, and a concise yet intense text – was in full swing by the 1980s. With its simple form and bold contrasts, she achieves a monotony in her frequent use of only three colours which makes people focus on something other than colour, that is, her messages. Her favourite typefaces Futura and Helvetica also focus on the delivery of messages in an objective and clear way.

In her early days, she reproduced images found in old magazines and photography. After processing the image, words were overlaid across the image. The words, once clichés taken from advertising, were reborn as statements imbued with socio-political criticism. In phrases less than ten words – such as ‘Your comfort is my silence’, ‘You delight in the loss of others’, ‘I shop therefore I am’ – texts are combined with images, her works leave a deep impression.

Untitled(Your Body is A Battleground), a work connected to the women’s rights movement, was produced in April 1989 in Washington, D.C., when a massive women’s rally against the abortion ban was held, and which was then pasted throughout the streets like a poster. Thirty years later, even in remote foreign countries, black-and-white images and matching phrases still resonate. This may be because they chime with reality in South Korea, where the constitutional discordance adjudication on the criminality of abortion was made in April this year. Her messages have targeted social issues such as gender, class and race, as well as issues surrounding political power, in addition to desire and mass consumerism promoted the media.

Installation views

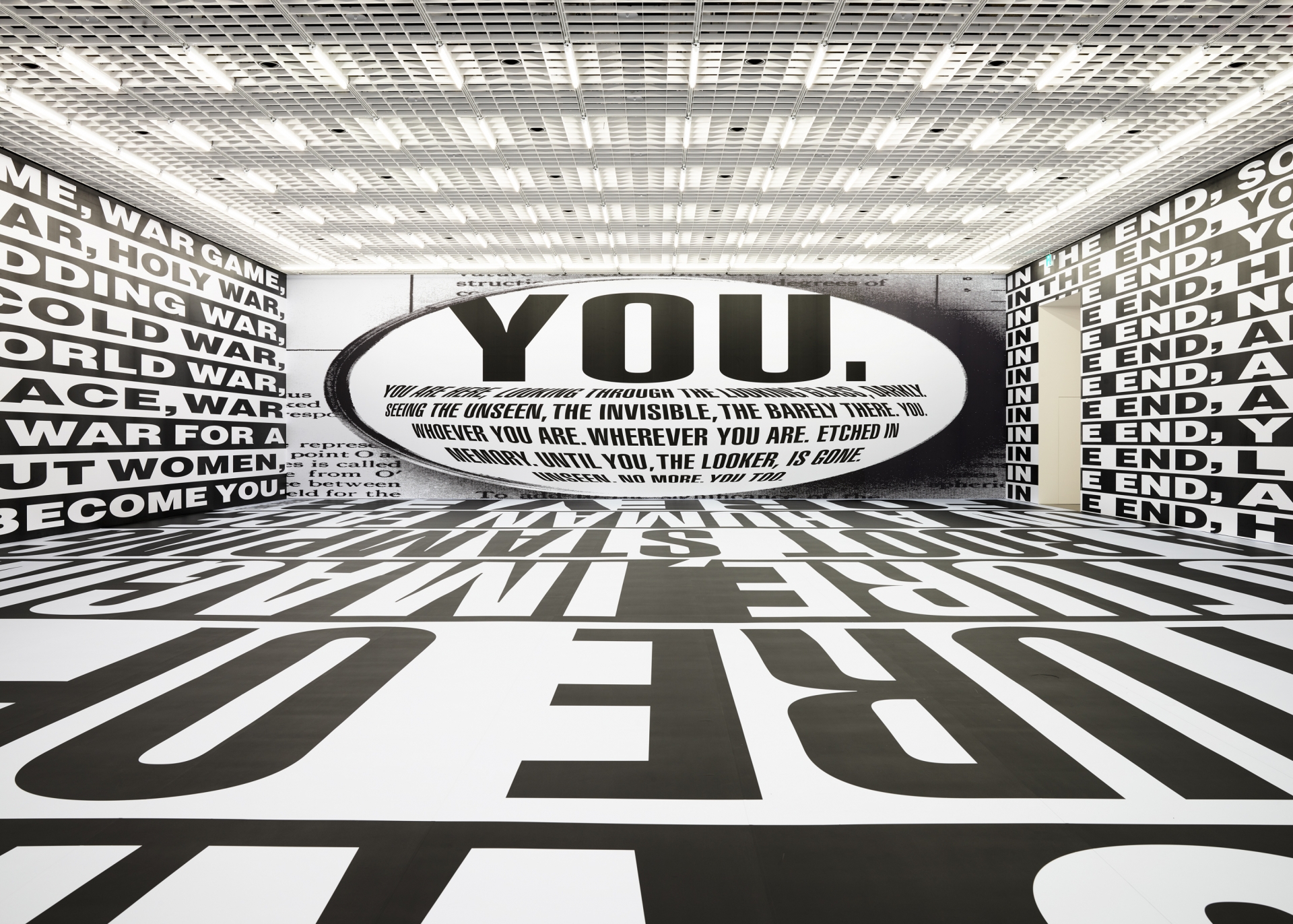

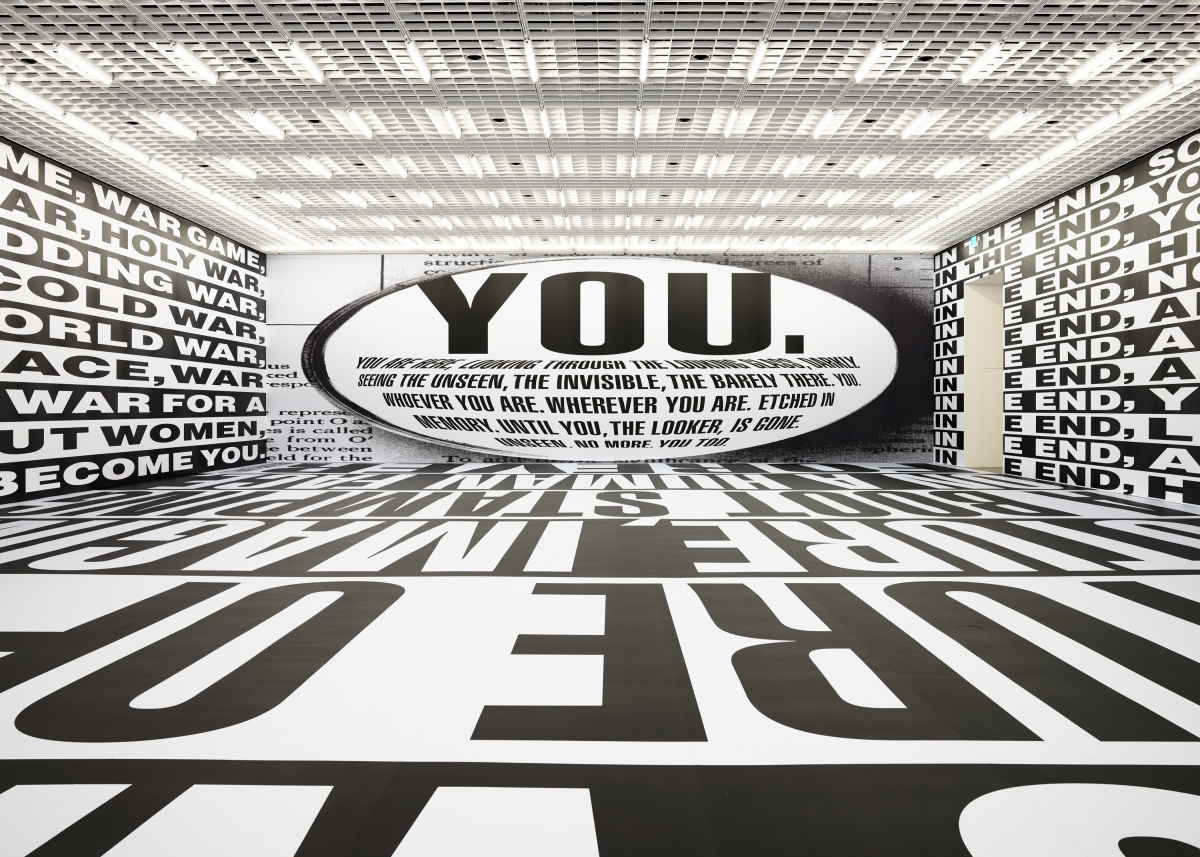

Barbara Kruger, Untitled(Forever), Digital print on vinyl wallpaper, 570×2,870×1,830cm, 2017

Texts that Stimulate Vision and Hearing

Untitled(Forever), a notable work that reveals the artist’s longstanding interest in architecture and space, is an installation that fills the walls and floors of the exhibition hall with words. Entering the gallery, visitors will face the letters “YOU” in a huge font size inside an oval block mirror image. Below that, there is a quote from Virginia Woolf’s book A Room of One’s Own (1929). The rest of the walls and floors are filled with sentences quoted from George Orwell’s 1984 (1949), in which each strap of black and white intersects and contrasts, maximising visual stimulation. Surrounded by large letters, it is a strange sight that can only be encountered in a movie.

These letters, whose size might be measured in metres, prompt one to think about the act of reading itself rather than the message it tries to convey. Most of the printed materials we encounter in our daily lives – such as books, magazines, leaflets, and posters – have a human scale: the size of letters within 10pt, spaces between letters and lines, a pragmatic system that enhances legibility in a small range where the eyes move. As the text grows in size, this system does not work properly: the reading experience approaches the viewing experience, and other aspects of the text begin to emerge.

The text of Untitled(Forever) stimulates hearing as well as vision. Reading is translated from the inside into the voice, leading to a sensory experience. It is probably because ‘“Reading” a text means converting it to sound, aloud or in the imagination’▼2, as noted by Walter Ong. The voice may sound different from person to person; the unified pattern and the contrasts achieved between light and shade, however, remind visitors of a coercive attitude or a commanding tone.

The sense of unfamiliarity – in which letters seem to speak – is also because the work is installed in an exhibition space set apart from external reality. In fact, we are frequently exposed to huge texts in the landscapes of our daily lives: the big words on billboards, banners, signboards, a large outdoor advertising structure that we tend to meet in the streets. Those big words, however, disappear at the time of their occurence, like a landscape passing in a window. Similarly, of all of Barbara Kruger’s site-specific works, the type of work that sits in the city – such as the street and the exterior walls of buildings – has received relatively low attention.

To point out one more thing, the intensity of the experience presented by Untitled(Forever) seems to be related to the fact that the text is “real”. It stands out when compared to the work of Jenny Holzer, a text-based artist, who applies text to the front of the building with a projection. The sense of text is relatively weak as if the flickering properties of light was inherited by letters and messages; Kruger’s text, fixed on the wall, on the other hand, has a weight that seems to exist in reality.

Of course, it can be dismissed as the simple act of affixing a digitally printed letter to a wall. However, comments such as these overlook the issues of production that arise when the scale of a work grows. Installation involves construction elements such as adhesion and film weight, but also qualitative elements such as image resolution. Barbara Kruger’s attempt at large-scale installations owed much to the development in printing technologies. Kruger once noted in an interview, ‘I need incredibly precise measurements to try and sync up how I want to visually and retinally engage the viewers. One great advantage about digital printing and working in video is that I have a chance to do these immersive environments, which are huge opportunities for me’. She also emphasised the method when making her early works, adding, ‘It’s not a collage, but a paste-up that cuts and attaches images’.▼3

Barbara Kruger, Untitled(Plenty should be enough), Digital print on vinyl wallpaper, 600×2,170 cm, 2019

The Context in which a Message Aims

Attempts to convey a fresh and provocative meaning can hardly be out of touch with the social context in which the text is first used. A good understanding of the context enhances the power of the message; in the opposite case, the meaning becomes ambiguous, failing to be delivered in the same way. The same is true of Barbara Kruger’s work. Kruger’s new work Untitled(Plenty Should Be Enough) was installed using Hangeul, the Korean alphabet, with the text translated from her critical comments on mass consumerism and modern desire. The vertical text, which is 6m high, does not touch the meaning like an arrow, incapable of reaching the target. Other Korean alphabet works, such as Untitled(Please Laugh Please Cry), and some English language works, also confuse visitors with their ambiguous messages. One might be generous with this, considering the broader constraints of language: if messages were always delivered correctly, such enormous effort to communicate with the world would not be necessary.

--

1. W. J. T. Mitchell & Barbara Kruger, ‘An Interview with Barbara Kruger’, Critical Inquiry Vol. 17, No. 2 (Winter, 1991), p. 448.

2. Walter J. Ong, ‘The Orality of Language’, Orality and Literacy, (New York: Routledge, 2013), p. 8.

3. Cedar Pasori, ‘Interview: Barbara Kruger Talks Her New Installation And Art In The Digital Age’, COMPLEX, Aug. 22, 2012.