Learning at the Bauhaus

In 1926, when the Bauahaus building in Dessau was completed, Konrad Püschel received an admission letter from Walter Gropius and began his studies at the Bauhaus the following year. He studied there until 1930, the year Mies van der Rohe replaced the previous director Hannes Meyer. For Püschel, the Bauhaus was a platform for new architecture and the artistic spirit, where the joy of youth was full of life all over the place. There were professors of a reverent spirit and vitality: Lyonel Feininger, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Oskar Schlemmer moved from Weimar, and their students – Josef Albers and Marcel Breuer – were selected as Jungmeister, making a contribution to the formation of art and design of the time. Püschel called the Bauhaus school building ‘Bauhauskapelle’.▼1

However, the architecture department was not established as part of the Bauhaus curriculum until 1927. Previously, Gropius had taken charge of the architecture department, but unlike other fields of study, its educational principles we re not established. Even Püschel thought that the Bauhaus was not meeting its goal, which it had set forth when it moved to Dessau.▼2 Eventually, Gropius appoints his office workforce as faculty members, and also hired Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer in order to strengthen the department; there was not enough time for these new professors to devote themselves to teaching. In order to overcome this condition, Püschel participated in an outside-school competition and practice with other students, while appealing to government agencies to improve curriculum and appoint more teachers. In the end, Gropius withdrew from the directorship in February 1928, leaving a brief statement that he was appointing Hannes Meyer as his successor.▼3

When the Bauhaus entered the era of Hannes Meyer, it became a cradle for Püschel to advance as an architect in his own right. Architectural education became the core idea, and the areas of design, construction, and supervision were included in the curriculum. The theory of architecture also focused on the ‘organisation of life processes’ of the future users. From the third semester, after completing the study of a theory of plastic forms, Püschel started exploring new housing types, functions (such as provision of optimum sunlight) and other elements, under the guidance of Meyer. He also worked on a new analysis of the issues facing city planning including the introduction of educational facilities and space for transportation and work.

Based on socialist ideology, Meyer’s Bauhaus considered the functionality and economic feasibility of buildings as fundamental concepts. When the former director Gropius asserted that ‘architecture ensures that they are able to live a new life with a new outfit and tools that meet everyday needs’, Meyer emphasised that it would be necessary to find agreement with the social aspect overlooked here: ‘the people’s needs instead of the need for luxury’. For him, architecture was the fruit of a meeting between utility and economy, and it had to remain as a matter of ‘organisation’. ‘A rchitecture is not an aesthetic process; architecture is just organisation.”▼4 Meyer’s radical assertion has become part of the Bauhaus’s new architectural theory. Püschel did not hesitate when accepting and practicing such ideological foundations. Based on a line of thought on new material, new structures, and new forms, Püschel learned how to fill architecture with social content.▼5 He also participated in the Laubenganghauser project led by Meyer. This experience had clearly become a driving force for the students, including Püschel, to advance as a socialist architect of a new era. His graduation certificate clearly stated that his major interest and achievement were a ‘design of residential complexes and especially dedicated to social aspects in the design’.▼6

Migration to the Soviet Union and Activities Afterward

‘I am now going to move to the Soviet Union and work there. It is where the true proletarian culture is being trained, where the society in which we are currently fighting for under Capitalism here exists, and where socialism is being formed’.▼7

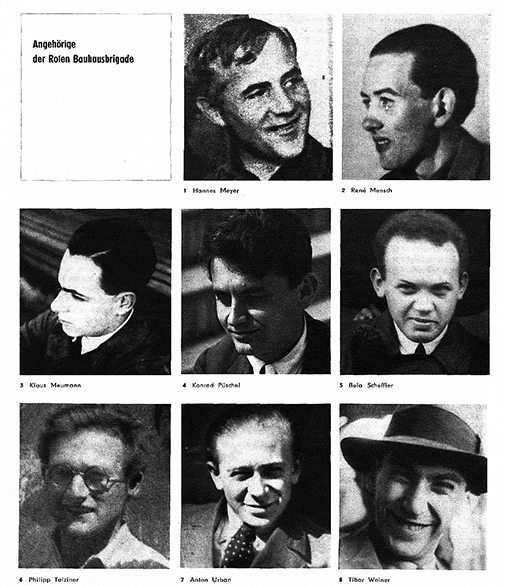

As a Communist and follower of Stalin, Hannes Meyer was unable to find any ground on which to realise his ideology in Germany. By the end of the year 1930, he gathered six students including Püschel, establishing ‘Red Bauhaus Brigade’ and heading to Moscow.▼8 Architects in the Soviet Union were builders on the front line of the economic development plan. Along with his students, Meyer acted as a builder, educator, and as an officer in the engineering process. He worked as a professor at the Moscow Advanced School for Architecture, participated in project development at the Giprogor (Russian Institute of Urban and Investment Development), and conducted city projects such as designing educational facilities, expanding Moscow, and planning of East Asia residential complexes.

At the beginning of his activities in Moscow, members of Bauhaus Brigade were drawn together to form ‘GIPROWTUS’, a trust responsible for the construction of technical education facilities. The restricted space and range of activity played a negative roll in terms of work efficiency and their quality of life. They did actually try to understand the Soviet society in a more profound way before embarking upon the project because it was important to grasp the economic conditions and trends for planning. While implementing the project, the Bauhaus Brigade asked the Soviet operative (GIPROWTUS) to dispatch them to other Soviet brigades, justifying a common goal of socialist construction. As the result of accepting this request, an effective conversation between them went on, and this work harvested even bigger fruit. The GIPROWTUS project in which the Bauhaus Brigade participated was to build educational facilities necessary for the industrialisation. Individual businesses suggested function, site and natural conditions, and social requirements. Then, based on these suggestions, they developed a general type of educational facility that could be introduced throughout the Soviet Union. Among them, Püschel participated in projects developing kindergartens and daycare centres. As Hannes Meyer did, what Püschel emphasised during the planning process was selecting materials that were locally produced and that even unskilled workers could handle in construction. Regarding the formation of architecture, he valued the plan composition that would follow the logic of function and economy, rather than the popular logic of proportion in architecture and the principle of minimisation of ornament—he referred to this principle as an ‘architectural principle of order’.▼9

This activity did not last long. In 1933, when the Soviet’s second five-year national economic development plan began, Hannes Meyer’s Red Bauhaus Brigade was dismantled. Even after the Brigade was dismembered, Meyer participated in several urban planning projects, and continued to be a member of the Architectural Academy. Other members participated in teaching and other projects in Russia or returned to Germany. In the meantime, Püschel joined the Gorstroiprojekt with Weiner and Tolziner.▼10 The task of the Soviet Union at that time was to construct a new socialist industrial city. The goal was to increase efficiency of technology and economy by linking industry and housing more closely and organising and building a city that would reflect the socialist ideology. However, the Soviet side intended to accommodate the classical tradition and national architectural heritage in place of city planning—this change served as a great challenge to the architects from Germany. When Stalin instructed the implementation of ‘National Design (Nationale Bauformen)’, German architects including Mart Stam and Ernst May could not accept it, eventually leaving the Soviet Union in 1933 and 1934. Some of the Bauhaus descendants were able to stay there until 1937, getting to know their Soviet colleagues more and sharing their experience and knowledge with them. In the meantime, Püschel had come to adopt the elements of geography and history here in the hope of ‘building a national socialism’ above all things.▼11 Nonetheless, as public criticism against the Bauhaüsler went in a harsh way in the Soviet Union, their architecture abruptly fell out of favour. By Stalin’s order, these architects’ contracts were terminated, and eventually, they were deported. In 1936, Hannes Meyer returned to Switzerland, and Püschel had to leave Moscow in the beginning of the following year.▼12

Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau / © (Püschel, Konrad)

City Planning to Reconstruct Hamhung

Hannes Meyer searched for a new site to construct a socialist city in Mexico, but due to a conflict with the government, he had to return to Switzerland without much accomplishment. He then passed away in 1954. By that time, Püschel had a chance to manage to realise his ideal in Hamhung. He was teaching at the Weimar University of Architecture in former East Germany when he was dispatched as the city planning team leader of the project to reconstruct Hamhung, which was destroyed during the Korean War. Since the early 1950s, the former East German government conducted a North Korean aid campaign in order to unite the communist world. When the Foreign Minister of North Korea visited former East Germany, Prime Minister Otto Grotewohl offered to support North Korea. Regarding this offer, the President Kim Il Sung immediately proposed aid for Hamhung reconstruction, and the East German government passed the resolution for the reconstruction from 1955 to 1964, establishing the executive branch ‘DAG (Deutsche Arbeitsgruppe Hamhung)’. Starting with 188 engineers, including Konrad Püschel and Hans Grotewohl▼13 in the first year, about 500 members of the working group were sent until early withdrawal in 1962.▼14 Püschel, who led the city planning of Hamhung reconstruction, strived to apply East Germany’s ‘16 Principles of Urban Design’▼15. This principle – developed out of the Athens Charter – reflected an action agenda to rebuild war-torn East Germany cities based on socialist principles; while the Charter focused on resolving problems to improve living conditions, the guiding aim of the principles of East Germany was to place emphasis on the realisation of the socialist ideal.

The DAG had to first solve the housing problem in Hamhung. They decided to demolish the housing type left by the Japanese colonial era and the one-storied wooden house that grew in popularity after the war, considering them as unreasonable. Püschel studied the form of traditional Korean cities – from Seoul to Mokpo – and reflected them in his reconstruction plan.▼16 To Püschel, the architectural value of buildings had to be ‘socialist in content, national in form’, the keyword asserted by Kurt Liebknecht who participated in compiling the ‘16 Principles of Urban Design’.▼17 However, prior to this, there was a design planned in Moscow for the reconstruction of Hamhung: a Neo-Baroque style plan with no consideration of the tradition of North Korea. Instead of following the plan, Püschel designed a new plan, studying nature and geography of Hamhung. Under the motto of ‘finding a progressive tradition in the past of the nation’▼18, he studied the traditional housing types along with their transition as well as the city structure, solving the issues behind the inherent forms of Hamhung.

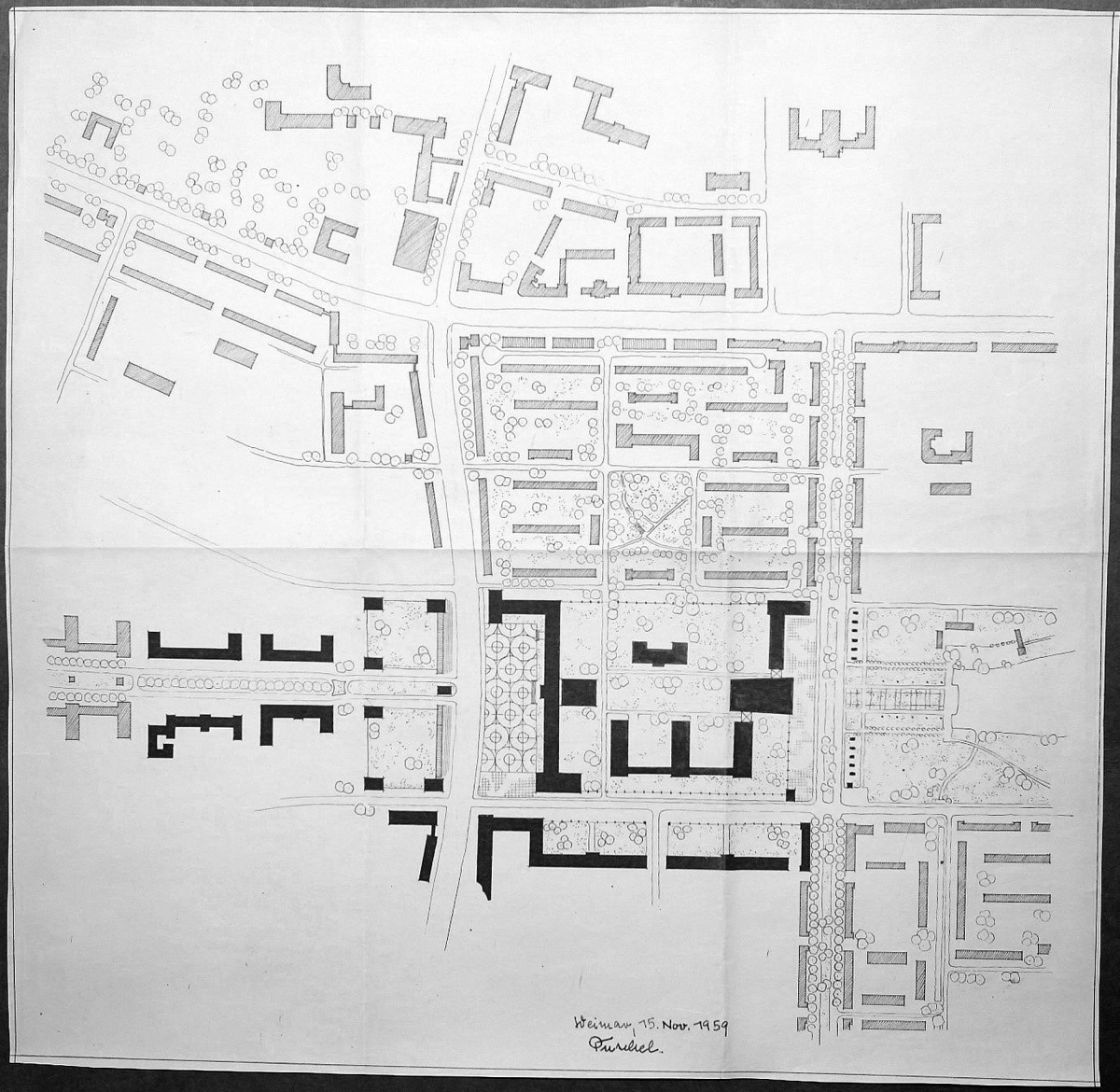

The elements of the residential complex design– orientation, sunlight, ventilation, neighbourhood – was acquired in the Bauhaus. It adopted the ‘Microdistrict’▼19 method for the composition of the residential area in city planning, and the districts were configured based on these 5-6 microdistricts.▼20 As a basic organisation in city planning, squares at the ‘centre of political power’, in which demonstrations and parades can be held, were displaced in each district. This planning method also followed the 16 Principles.

Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau / © (Püschel, Konrad)

He proposed adopting the Central Square as well as high-rise residential buildings in the city centre. In the Central Square of Hamhung, the national institution of Hamgyong province and cultural facilities had to be provided. Until 1959, when Püschel was overseeing the city planning, the construction of a national institution home to the political life of the region and the construction of cultural facilities for ordinary people were different topics. For Püschel, the notion of the nation prevailed that of the culture. What Püschel considered most important during this process was ‘how Communism works in city planning, and specifically how this Communism serves as a crucial factor when deciding the form of the centre’. To him, it seemed that ‘life is not something that is just made up by culture’. If the framework known as the nation perishes, life cannot survive solely on culture.▼21 Thus, for Püschel, a government institution that presented national power had to be located in the centre of the city, representative of strength and a symbol of power in the form of a high-rise building.

However, at the end of 1950, his successor Karl Sommerer argued city planning must be more democratic; people’s lives are more important. He claimed that the administration buildings should not be located in the Central Square.▼22 He also designed the Central Square around the cultural facilities, and thought that low-rise format was more appropriate for the national institution. Unlike Püschel’s design, the composition of the building should be more open to the public and stress the relationship with Nature. For Püschel, the design of his successor was problematic as a presentation of the socialist ideology. Yet he had already returned to Weimer. He objected to Sommerer’s design and tried to persuade others of his intentions, but in the end, he could not form the architecture of the Hamhung Central Square in a way that would best symbolise the socialist character.

In 1962, when the dispute between China and the Soviet Union broke out, the DAG had to be withdrawn unexpectedly. Afterwards, the North Korean government alone built the Hamhung Grand Theatre at the Central Square in 1984, in a form unlike that proposed by the two architects.

Restoring and Commemorating Bauhaus Heritage

The divisions during the Cold War era not only interrupted one’s overall sense when assessing the results of the architecture and city planning designed by Püschel, but also obscured the labour of his mentor, Hannes Meyer. Their architecture and city planning are a part of Bauhaus history, but architectural historians do not consider this as a subject of study. Since its significance and value were not questioned, the contents of ‘socialism’ were avoided when describing history. In this process, the architectural values of another Meyer were also forgotten. Adolf Meyer played an important role both as an architect and in the Bauhaus. However, the historian Leonardo Benevolo confused his name with Hannes Meyer and Giulio Carlo Argan who described the history of Gropius and Bauhaus misrecorded the name of Hannes Meyer as Mayer. Sigfried Giedion did not at least confuse the two, but he did not devote much space in his books to them.▼23 Perhaps this was due to the prevailing mood of condemnation among historians because the communist Hannes Meyer had turned away from his promise to separate the Bauhaus from the political sphere, a pledge he made to Gropius at the time of his appointment in the Bauhaus. Yet Gropius himself also moved the school building from Weimer to Dessau for political reasons, and he knew about Hannes Meyer’s political orientation and his characteristics as socialist.

Along with Meyer, the architecture and city planning by Püschel were forgotten. The Bauhaus building in Dessau also seemed to have been forgotten for a while and left in ruins after World War II. Nonetheless, after returning to East Germany in 1976, Püschel actively participated in the restoration of the Bauhaus school building. Not only did he agree to superintend and make a consultation, he also took charge of supervising its construction. This was how Bauhaus the celebrated its 50th anniversary. Later in 1981, Bauhaus held a private exhibition of Püschel’s work, highlighting his efforts in architecture and city planning as a Bauhäusler.

1. Konrad Püschel, Wege eines Bauhäuslers. Erinnerungen und Ansichten (Dessau: Anhaltische Verlagsgesellschaft, 1997), p. 22.

2. Ibid., p. 40.

3. Ibid., p. 41.

4. Hannes Meyer, ‘Bauen’, in bauhaus, 2. (1928). H.4, p. 12f.

5. Püschel, p. 55.

6. Ibid., p. 54.

7. Hermann Funke, ‘Wer hat Angst vor Hannes Meyer?’, in Zeit., no.8 (1967), p. 5.

8. Other than Püschel, there was Philipp Tolziner, René Mensch, Tibor Weiner, Klaus Meuman, Béla Scheffler, and Anton Urban in this group.

9. Konrad Püschel, Die Tätigkeit der Gruppe Hannes Meyer in der UdSSR in den Jahren 1930 bis 1931, in Wissenschaftliches Kolloquium vom 27. bis 29. (Okt. 1976) in Weimar an der Hochschule für Architektur und Bauwesen zum Thema: 50 Jahre Bauhaus Dessau, p. 470.

10. Ibid., p. 470.

11. Winfried Nerdinger, Philipp Tolziner. ‘Lebenswege eines Münchener Bauhäusler’, in Münchener Beiträge zur jüdischen Geschichte und Kultur, H. 2 (2012), p. 59.

12. Püschel, Die Tätigkeit, p. 472.

13. He was the son of the Prime Minister Grotewohl, and his wife jointed the DAG as well.

14. Reference: Bundes-Archiv Berlin, DC20-630 (Bereich Außenpolitik 1950-1959).

15. The East German government announced this legislation on 6 September 1950. A colleague of Püschel, Edmund Collein, and the director of city planning for the reconstruction of East Germany, Kurt Liebknecht, wrote this about the reconstruction of several East German cities including Berlin that were destroyed by World War II. This legislation stands on the extension of the Athens Charter and reflects the political theme or monumental buildings, and the Soviet’s ideology as socialist city that emphasises demontrations.

16. Konrad Püschel, ‘Ein Überblick über die Entwicklung und Gestaltung koreanischer Siedlungslagen’, in Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Hochschule für Architektur und Bauwesen Weimar, IV. Jg. (1958/59), H.5, 1959, pp. 459-477.

17. Lars Grummich, Der sozialistische Städtebau und sein Erbe (Hamburg: Diplomica, 2012), p. 19.

18. As the second term of the ‘16 Principles of Urban Design’, Püschel considered the topography of the Banryong Mountain and Songchon River in Hamhung. He proposed an axis of vision ranging from the Center Square to Songchon River for the composition of urban axis, while reflecting Ondol style and sedentary lifestyle in the form of residential plan.

19. This is a unit of city organisation that meets the socialist life in East Germany. It is a residential area that has housing, commodities, sales facilities, a nursery, kindergarten, educational facilities including elementary and middle schools, and medical facilities, in which the urban transportation system takes the shape of an outline. (Reference: Kim Mina, ‘A study on the planning of microdistricts in postwar North Korea’, Ph.D Thesis, Hanyang University, 2018.)

20. Bezirk Zentrum, Hoesang district, Banryong district, Sapori district, and Hamju district were configured into 6-11 microdistricts.

21. Püschel’s letter to Sommerer on November 18, 1959 [Source: Bauhaus-Archiv Dessau, Püschel, Korea, I_010202_D. p. 1.].

22. Sommerer’s letter to Püschel on March 21, 1960 [Source: Bauhaus-Archiv Dessau, Püschel, Korea, I_010202_D. p. 2.].

23. Hermann Funke, ‘Wer hat Angst vor Hannes Meyer?’ In Zeit. No. 08, 1967, p. 5.