Nathalie Du Pasquier is the artist she has always been. She is a painter, she is a sculptor but she is also in the contemporary mood of working between mediums, melding perspectives, fusing bi- and tri-dimensional ways of working to the service of environmental and yet still domestic effects. She doesn’t want to forget her past life as a designer, co-founding the influential Memphis group lead by Ettore Sottsass, which delivered in less than a decade a wide range of colourful, crafted domestic items. Du Pasquier doesn’t want to remember it as the defining moment but rather as an important episode in her artistic life. Born in Bordeaux with a history in textiles and printmaking ‘Indiennes’ family, she escaped this straight Bordeaux lifestyle to a more adventurous life by traveling to Africa, Australia, and India at the age of 18 to 19. Running away, dropping out, experimenting with states of mind and impulsive daily drawings, all shaped her young life. It was probably Africa’s visual realm that offered the starting point in the patterning of her vision and the arrangement of details on pieces of paper, and presenting possible entry to a newly reconstructed world. An unconventional way of living and thinking, understood as freedom and pleasure could be thought to be her motto. Du Pasquier, back in 1987, decided to become the painter. Her experience as a designer made her confortable with axonometric projection, with more technical forms of drawing and designing becoming tools and methods to be introduced to more conventional easel painting. Composition is the way of putting things together, such as geometrical forms, daily objects, bottles, facetted glass, shoes, and so on. Think of the Purists, Amédée Ozenfant, Fernand Léger, Le Corbusier, and how they look at their objects, look at their colours (off green, off blue, off red) and then look to Du Pasquier and then, the connections are clear. The Memphis group used brighter and more active colours as a statement, exploiting the primary blue, red, and yellow of the mondrianesque with its own twisted shapes and non-western quotations. Her relentless play between two and three dimensions has become her signature style and forms her ready recognition by those in today’s art world.

Kim Seungduk (Kim): What motivated you to travel extensively when you were young? Then you moved to Milan in 1979, what was art scene like in Milan at that time?

Nathalie Du Pasquier (Du Pasquier): I had only left Bordeaux twice before coming to Italy. Once in 1975 when I was 18 years old, I went to West Africa for 9 months and then the year after I traveled to Australia and India for about 4 months. Many young Europeans did this at the time. It was a way of understanding what to do with your life, of discovering whether there was an alternative to the world I had known up until then. That period was also very interesting because I think I came to understand that my life had to develop and extend away from where I originated. I wanted to live somewhere other than France. So I came to Italy and in September 1979 I was in Milan, which I immediately liked and where I remained. I knew nothing about the art scene and was not even interested. I knew nothing about design either.

Kim: In an interview you gave in 2016, you recalled your first encounter with art. What was your childhood like in Bordeaux? What led you to become an artist?

Du Pasquier: My childhood in Bordeaux was very normal, quiet, with nice parents who would show me things and discuss their interests with me. My mother was the director of Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Bordeaux and my father was a virologist. I did not draw or paint or play any musical instruments, and I was not very good at school. I don’t know if these were ingredients that have made me into what I have become. Probably.

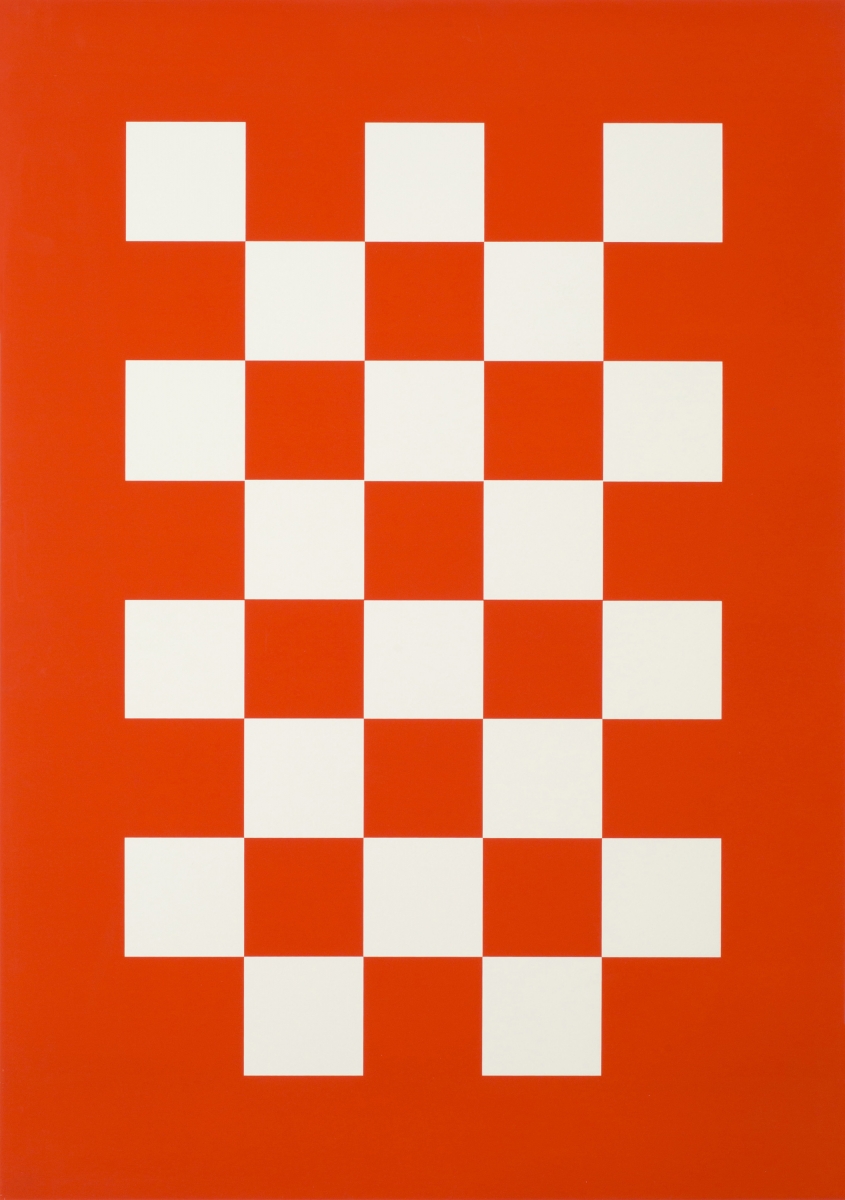

Kim: Did Africa teach you about pattern? The detailing of their fabric, in particular? How do you see the issues facing pattern in general and how did you use these questions in your own work? Did you formulate some kind of theory of colours or range of references drawn from the history of art?

Du Pasquier: It is true that when I arrived in Milan, even though I had not undertaken any formal programme of study, I began working, selling patterns for the textile industry, which tended to be florid in Milan at that time. It is also true that when I was in Africa, I was charmed by the way people dressed in their beautiful printed fabrics. These designs were bright and often felt full of humour because of the way people were wearing them. That probably stayed in my memory when I myself began to design textiles, but I never tried to design African patterns probably because we are not as beautiful as people in Africa and these patterns would not look as good on us. I think I just moved with the flow that has always existed, of influences traveling through countries, changing at each passage, all victims of fashions and trade rules. For hundreds of years textiles have been really interesting testimonies of exchanges between cultures, ever since people began to travel wearing their own clothes. In a way I was designing textiles, and so no particular science was needed, no theory was needed. The client would like it or not.

Kim: You are essentially a painter, and, I will add, a classical painter. Do you agree with that? I ask this because of your involvement with objects, furniture and the 3D, and so your way of drawing and painting has to do with technical methods taken from the 3D world. Axonometry for instance. How did you handle these techniques and methods?

Du Pasquier: Yes, I am a painter and you can call me classical because I paint with oil on canvas and very often represent things that are positioned in front of me. That said, however, I am not an impressionist, as I am more interested in painting how things are. The oriental way of representing uses axonometry to render architecture or artifacts. It is not really a technique, it is maybe a ‘pre-perspective’ way of working, and yes it was also the way I was presenting my design projects because you can show more things in one drawing! There are so many things I have looked at over time and many of them, if they touch me, leave a trace, and very slightly alter the way I see things.

Kim: As for your still life compositions, these present a very special and interesting quality in your work. Your way of managing things and arranging these things bring us somewhere beyond thingness! Could you say something about still life and things in your work?

Du Pasquier: My main subject is still life, so I am of course interested in objects and things, in piles of things, groups of things and the relations between things. Early on, before I started painting, I came across a book on Korean paintings of objects. I was fascinated by how in representing objects you can express so much, building a construction out of the different objects and giving a meaning by choosing what to represent. At the same time, you don’t need to say anything, there is no message, only a silent one. My mode of painting with oil on canvas is of course very occidental and I am not trying to imitate any style or anybody. I like the silence and the time spent on the painting.

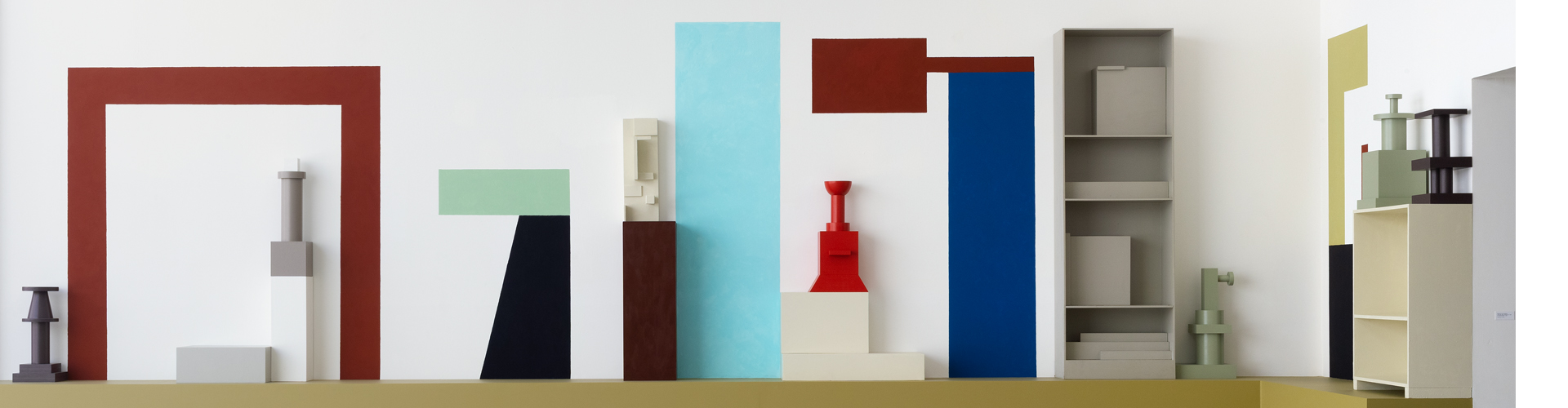

Kim: Your work is constantly shifted between 2D and 3D. How can you explain this? Is it because of your involvement as an artist/designer between surfaces and volumes?

Du Pasquier: About 20 years ago I began to build the things I wanted to represent and that is the way I became interested in abstraction. The things I build are geometric compositions of painted pieces of wood. They do not represent anything and are not recognisable as anything yet existing. When I represent them, the resulting paintings no longer look like still life because what is represented is not identifiable, even though they are as precise as my previous paintings. That is how at a certain point I began painting abstract things directly on the canvas and not using models any more. That was also the time I started organising compositions between paintings and things. Why not? In the end a painting is an object just as a vase is an object. This is something that perhaps emerges years ago, when, during the Memphis years, following in the wake of Sottsass’s notion of breaking the hierarchy between high and low culture, we would put together a plastic laminate together with a piece of marble or silver.

Kim: How has your work evolved? Do shows offer you a new way of getting things into production?

Du Pasquier: At this moment my work is changing a bit because of the number of exhibitions in which I am involved. Maybe that is also why I have started, more than ever before, to put different categories of things together. It is as if, for many years, I had been working on a long alphabet that I am now using to create new sentences. I am using my works as raw material to build new work. Maybe that is also the effect of age; you gather close what you have done and you start seeing the design, the pattern it has devised.