At the start of this project, a consensus was formed around the fact that the unique identity of Cambodia should be used as a tool to counterbalance or respond to the universalising effects of globalisation. We sought methods that would effectively strike a balance between the vernacular and the modernity imposed by globalisation, which entailed significant research and analysis trained on the local architectural language. We strived to mediate vernacular architecture and common spatial structures found in modern educational facilities.

Globalisation: A Subtle Act of Destruction

The concept of globalisation signifies how an accumulation of capital surpasses the regional and extends to the world. Globalisation proceeds in a hybrid fashion, in which modernised systems and cultures are rapidly disseminated and the integrated into the networks of other countries. Modernised educational facilities are also a type of programme established under the capitalist system. Accordingly, the dissemination of western education systems can create conflict with local traits and needs. Not only do they transform the region’s unique cultural systems, they can also lead to the dissolution of traditional lifestyles.

The globalisation of architecture, led by star architects and large Western architectural firms, has progressed in a commercial way, meaning that architectural projects have been recreated as a type of product and exported to developing countries.▼1 Here, architecture is a product founded on a superior image that has been attained through technological refinement. The business of the star architect is often accompanied by a insubstantial understanding or ineffectual tolerance of local culture. In general, the approach is limited to simple allusions to the symbolic imagery of a certain region, or overexaggerating traditional styles. Such a superficial architecture, which adopts local cultural vocabularies without critical reflection, is brought about by a lack of consideration of the specificity of the region based on cultural co-existence. These issues impede a sense of continuity in local cultures as well as enable their subtle destruction.

Previous discussions on globalisation have shed light on how capitalist expansion encroaches upon local cultures. Today, this discourse has transitioned to focus on how one might understand vernacular elements on multiple levels, how to critically accommodate them and how to seek out the middle ground in their use.▼2 Throughout the growth of globalization, modern educational facilities have proliferated worldwide, with the aim of producing labour resources that will sustain the capitalist economy. Education is therefore commercialised as a single system and its programme, known as the school, has come into existence by typifying certain spaces necessary to education (classrooms, administration offices, gymnasiums, auditoriums, etc.). As such, formalised programmes and archetypal spatial structures have ridden the waves of globalisation, finding wide application across different regions. If one were to define the vernacular as the manifestation of the cultural, native and social systems, it is inevitable that the influx of modern educational programmes will bring about conflict between modernity and the vernacular. As such, there is a need for greater understanding and identification with a conciliatory architecture, which could establish a sense of harmony between two disparate characteristics, as well as a need for design methods that pursue co-existence rather than indiscriminate decision-making.

The Vernacular and the Architecture of Cambodia

‘It is of such extraordinary construction that it is not possible to describe it with a pen, particularly as it is like no other building in the world’. While the sense of awe expressed by the Portuguese monk Antonio da Magdalena in 1856 when visiting Angkor Wat in Cambodia may be no exaggeration to those who experience it today, the architectural accomplishments of the Khmer Empire did not succeed at continuing a legacy throughout the tides of its complex and multi-layered history. With the exception of the short-lived proliferation of ‘New Khmer Architecture’▼3 established with the support of the royal family and the architect Vann Molyvann▼4 following independence from France in 1953, and the sequence of tragedies that followed, such as the 1970 coup d’etat, dictatorship, civil war, the American invasion, and genocide carried out by the Khmer Rouge has brought about a period of cultural reticence to Cambodia.▼5 With the influx of foreign capital in Cambodia today, a new architectural terrain, differing from the vernacular context, is now in the making. Yet, it has progressed in a way that incites a radical dissolution of the vernacular, according to an economic logic accompanied by an absence of an understanding of the local characteristics and culture. These circumstances do not largely differ from that of South Korea, which shares in this past experience of a complex modern and contemporary history.

While conducting this project, we tried to compose a future-oriented educational space which simultaneously understands and respects the traditional context, rather than imposing new architectural concepts and artificial solutions. Spatial concepts were sought from traditional Khmer architecture, colonial architecture, and Cambodian vernacular architecture, in order to appropriately respond to the climate and the environment. A number of beautiful and diverse contexts were discovered, such as galleries and emptied courtyards, corridors arranged adjacent to the open air, the moderation of direct sunlight through the use of depth in the space of the outer wall, the rough surfaces which add a sense of the archaic, the colours and textures of the local materials, and the people who gather in small groups to actively participate in discussions. By integrating these elements, we tried to create an educational space in which the values of tradition, the present, and the future could coexist.

ACLEDA Institute of Business Campus Project - Vernacular Modernity

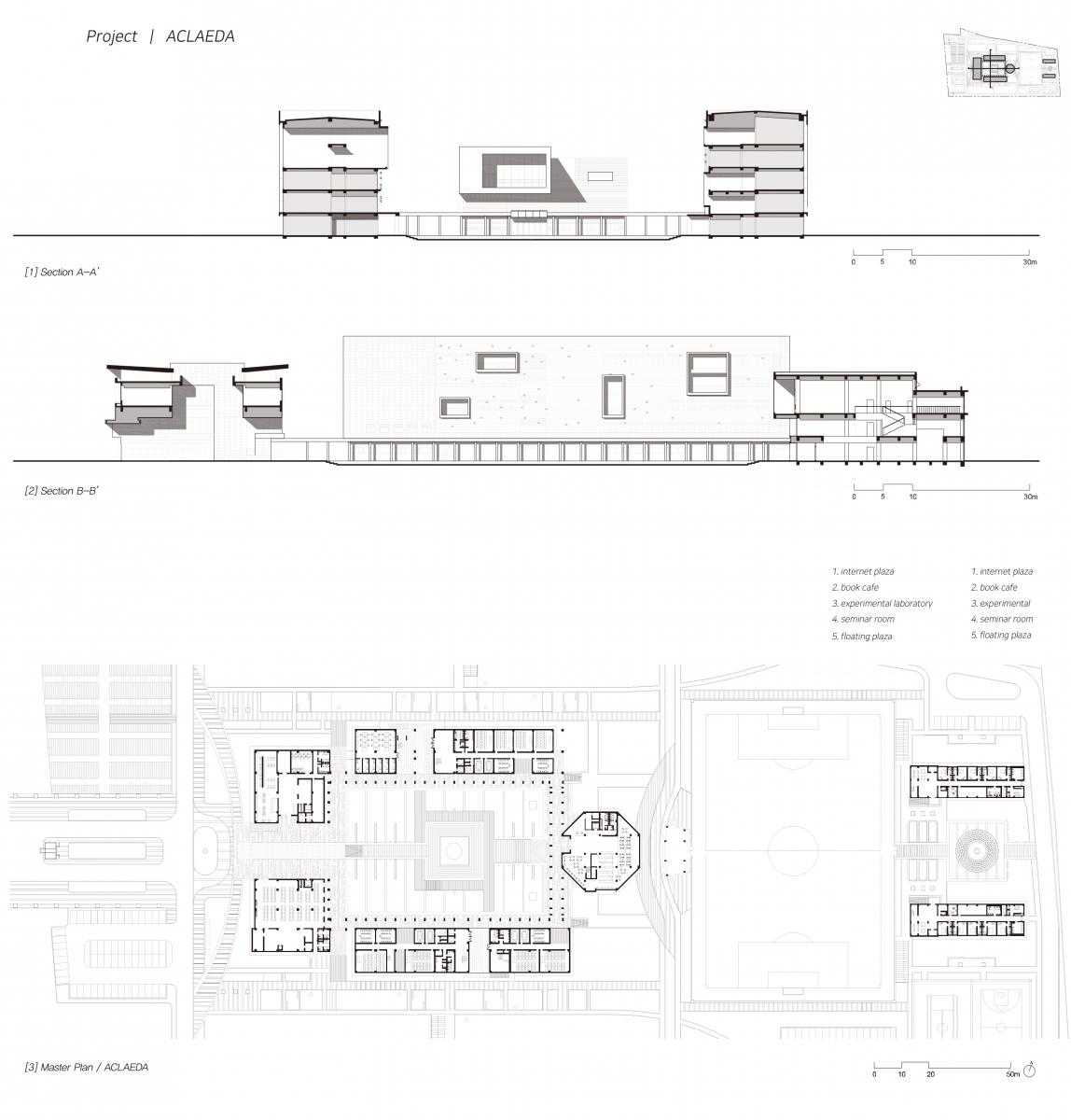

The ACLEDA Institute of Business Campus project planned a courtyard of 90 × 56m (including the gallery) at its centre. As of early 2019, the first stage of the design has been completed, with the four buildings, the Administration Building, School Building-1, School Building-2 and Library, surrounding the courtyard. The proposed second stage plans to construct four more blocks which surround the courtyard will add another layer, as well as a dormitory block at the rear of the sports field. Many elements were inspired by the architectural characteristics found in Angkor Wat, such as the entrance that opens towards the west, the galleries surrounding the courtyard, and the ratios within the courtyard.

The campus was planned so that the outer regions and programmes could establish a sense of harmony. First, upon entering through the main entrance, one passes through the peripheral areas for parking, and then passes through the administration building. A void of 21 × 26 × 9m has been placed at the centre of the Administration Building, made up of administrative and office spaces, and the student cafeteria. The void, which opens to the sky, divides the volume, giving the building a sense of depth and introducing light and air. The sloping roof was designed to illuminate the Administration Building as the gateway to the campus, and by setting apart the roof and the slabs, the building becomes an appropriate receptacle of heat from the sunlight. Also, a white louver, made of perforated metal panels, has been attached as a decorative element to the western façade, while also responding to climate conditions.

When passing the Administration Building, one comes face to face with the courtyard. The ㅁ-shaped courtyard is simultaneously a symbolic space and a place of leisure and of exchange. Following the boundaries of the courtyard, a gallery continues connecting the surrounding buildings, and the regular arrangement of the gallery columns adds to the stillness of the atmosphere. The height and ratio of the surrounding buildings were also modified to attribute a sense of spatial abundance. A multi-dimensional and visual interaction between the courtyards and the void spaces was intended by turning the voids of the surrounding buildings towards the courtyard. In order to embrace natural changes, the courtyard was emptied and landscaping was kept to a minimum. The most outstanding architectural feature of this project is the ‘diverse interaction spaces composed of dimensional voids’ (hereinafter void spaces) in the educational blocks and libraries. The galleries, the corridors and the void spaces organically overlap and connect, offering a central point of contact between the wide range of activities that take place in the school. These void spaces are intricately tied to the courtyard of the campus from the ground floor, or even on each floor of the buildings. The void spaces in terrace form have been designed for the multiple uses of seminars, class prep, and rest. This was an attempt to activate small-scale communities as educational spaces of convergence, at a time in modern education where informal education spaces have become more important. The educational block has been designed to take into consideration traditional colours and textures, extended void spaces, and the use of light and shadow, while evoking a sense of depth and rhythm from the outer wall through the louvers and void spaces.

The library is a regular and octangular form with an irregularly placed terrace as an external block, bringing variety to the serene atmosphere in the courtyard. This octangular form was applied at the request of the client, to signify nirvana, the final goal of Buddhism. The internal spaces are configured in a variety of intersecting voids. Such a decision is a reflection of the recent trend to re-evaluate libraries as public spaces, and of the efforts to increase accessibility to information. The public nature of the space, composed around the campus courtyard, continues up to the third floor terrace while trailing the library’s internal voids. The internal book storage space visually opens up as it comes face to face with criss-crossing open voids. On the upper level, a horizontal skylight has been placed to allow sunlight to extend into the library through the voids.

For a Modernized Vernacular

This campus project followed the process of not only responding to the physical environment but also articulating the social conditions established by the local culture and history. The campus was realised by negotiating and reconciling the opinions of interest groups from a variety of backgrounds hailing from across the state and the wider region. In this process, the architect was called upon as a mediator to consider the inherent socio-cultural significance of the site and the new programmes. The realisation of a modernised vernacular is only possible when one understands and accepts the unique values that the local architecture that has been established. The era of select experts authoritatively proposing architecture, and its importation and indiscriminate acceptance, has now passed. The key question remains as to whether an architecture founded on sustainable culture can still be created within the tides of globalisation with a respect and understanding of the vernacular. A modernised vernacular must be established through a co-existence based approach, which opts for a plentiful conciliation rather than a clear-cut concept. These are values that must be embraced by sustainable architecture, transcending generations and regions.

--

1. The transparent glass box of the Apple Store, which has recently proliferated throughout the world, is an example of the commercialization of architecture.

2. As two representative viewpoints; first, Kenneth Frampton adheres to the perspective of critical regionalism in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essay on Postmodern Culture emphasising topography (terrain, light, climate) as a definitive element of architecture. The use of the material, tactility, traditional expression methods of vernacular architecture, and ensebased experience, such as the visual, touch and the auditory, are all seen as important elements to express regional characteristics. On the other hand, in Technology Place and Non-modern Regionalism, Steven A. Moore discusses the need to understand technological or placebased concepts and for this to be absorbed as regional architecture from the political and ecological perspectives. This reveals the coexistence of voices, which calls for internal awareness about vernacular characteristics and the guarding of a sense of self-awareness about globalisation.

3. As a cultural movement fully supported by the Prince at the time, Norodom Sihanouk, dating from 1953 (independence) to 1975 (the incumbent Khmer Rouge regime), 1922 – 2012, its characteristics lie in the use of new materials, references to traditional architectural technologies, the application of natural ventilation and shadow, and the use of traditional relief patterns.

4. Vann Molyvann (1926 – 2017) was an architect who led the movement behind Cambodian New Khmer Architecture. He left many works of architecture that integrate the principles of tradition and the modern. (New York Times, 2017. 9. 28)

5. Michael Falser, Cultural Heritage as Civilizing Mission: From Decay to Recovery (New York: Springer International Publishing, 2015), p. 150.