‘Min Joung-Ki’

KUKJE GALLERYJan. 29 – Mar. 3, 2019

Min Joung-ki has been defined as a Minjung artist. As a founding member of 'Reality and Utterance', which led artistic attitudes in Minjung in the 1980s, he participated in various exhibitions such as the 'Foundation Exhibition', a show known as the ‘candlelight exhibition’ and in ‘City and View’, as well as the '15 Years of Minjung Art' in 1994 and 'Reinstatement of Realism' in 2016. Although he has not revealed strong nationalistic colours or tendencies towards protest like other artists of Minjung, a series of historical connections offer reasonable basis for calling him a Minjung artist. The so-called ‘barbershop painting’, which he created in protest at aesthetic rigorism, linked him to Minjung Art for a long time.

However, it is somewhat premature to define all the work of the artist under the concept of Minjung Art, which has not yet been sufficiently studied. In Minjung Art, there are differences in the direction of each artist's practice, as there are artists who stick to its observable principles and those who seek to change over time. Min Joung-ki, who participated in Minjung Art through aesthetic themes , rather than political subjects, is an artist who belongs to the latter. It means his work may be compatible with folk art, but that is not all. Minjung Art, which has an essential place in the history of Korean modern art, needs to be approached individually, not just by through the lens of the times.

This solo exhibition of Min at Kukje Gallery needs to be viewed from this standpoint. The artist, who has become a senior figure on the Korean art scene, presents 13 new works alongside 21 older pieces and asks the audience to look at them more broadly before defining them as Minjung Art. The exhibition, which uses both the buildings of the Gallery, seems like a venue for the renewal of a series of discussions that have modified over the course of the artist’s life.

Min Joung-Ki, Mugan-ri at Mt. Yongmoon, Oil on canvas, 211.5×245cm, 2007

What is in common with the past is the fact that Min Joung-ki still paints the landscape. Unlike in the past, however, when he was classified under Minjung Art by drawing landscapes that depicted the lives of the people, the materials he draws upon today vary from urban landscapes, natural environments, to scenes in novels. What difference does note when drawing scenes close to the lives of the people from the past? If, as Karatani Kojin said, ‘the landscape is found by “internal humans”’, what kind of inner world does today's Min paint and in what kind of landscape? The various scenes presented in the exhibition and the multiple ways of pondering them allude to the introspective nature of the artist.

The most striking feature is that his landscape paintings refer to the format of ancient maps. Mukan-Ri Jangsudae at the entrance of the exhibition not only contemplates the village, but also brings in the nearby mountain and water, and the name 'Jangsudae' and 'Mukamdong Stream', the lines written on rocks. Usually, maps value accurate information based on scientific measurements, but it is ironic that the form of maps is used for landscape paintings that depict such personal impressions.

The explanation can be found in a field survey conducted by Min with Choi Jonghyun, an urbanologist, from several years ago. What they called a ‘human geography trip’ is not a one-time visit to a place, but a repeat of pre-survey of the site and a repeat of the following data organisation. It is natural to assume that the scene captured by the Min was affected not only by visible scenery but also by the information obtained throughout the investigation. When presenting the new landscape in the exhibition at the Kumho Museum of Art in 2016, the art critic Choi Min also pointed out that ‘the dimensions of intelligence such as seeing and knowing that are combined in his paintings’.

The ancient maps of Joseon, which he mostly borrows, also have pictoriality, unlike other maps. The old maps of the Joseon Dynasty are closely related to paintings, as the painters who produced the maps at that time were 'wary of blurring the distinctions between maps and paintings'. This is why it is appropriate to distinguish maps and paintings in terms of their different ways of viewing the world, not of dividing them into scientific information delivery and personal psychological depiction. The landscapes of the Min are designed to reveal history and other contexts that are not immediately visible by referring to the ancient map.

A 'multi-perspective composition' is a formative feature for viewing objects in different ways. Not only works that follow the style of the map like ‘Suip-li (Yangpyeong)’ that looks down the entire village from a high point of view, but also ‘Baeksecheongpung 2’, which seems to have described the near landscape according to this perspective while also applying different viewpoints to different subjects. As with traditional Oriental painting, it is possible to find the best viewpoint to show the subject and use the various compositions within a single screen. It is not just a painting of what one saw, but also evidence that the artist painted what he walked and visited. The landscapes of the Min are more like 'a canvas as a map' which looks at the overall context rather than 'a canvas as a window'.

The difference to old maps referred to as landscape paintings is also distinct. Although the method of showing results of the survey and using different points of view is the same, the attitude of dealing with the ‘temporality’ that results from the study is in this contrast. The multi-perspective composition drawn by moving from place to place inevitably presupposes the passage of time. Unlike the map that erases the time to record 'the current facts', the landscape of the Min Joung-ki actively utilises 'temporality'. It is to insert the material found in the past field investigations or history into the landscape.

The series 'Riverside Landscape' mirrors Min Joung-ki's attitude to put temporality into the screen. By talking about a novel of the same name written by Park Taewon, the work unpacks the genre based on time known as 'story' on the canvas. If the book showed the flow of time according to the page order, Min aggregates the time on the canvas through various perspectives and configurations.

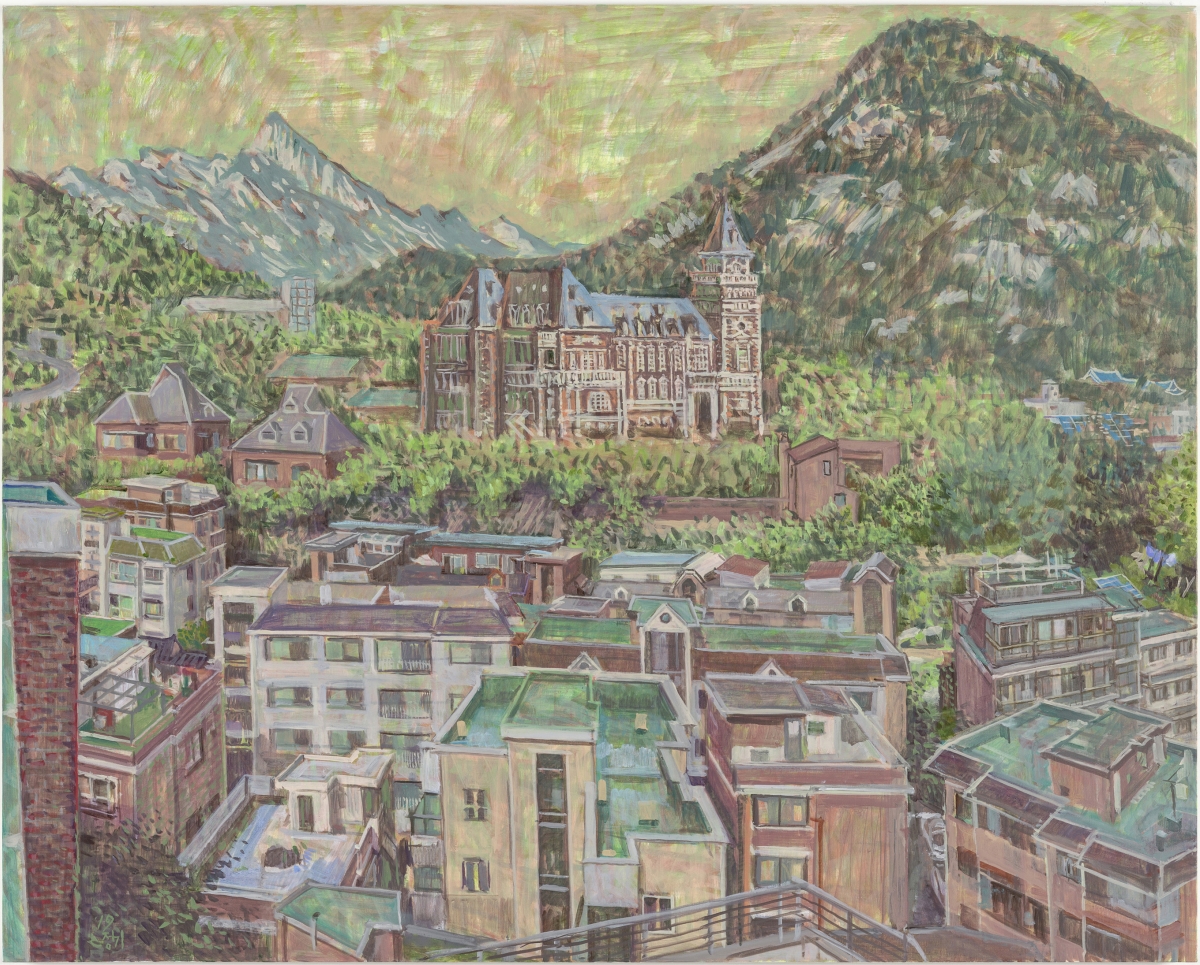

Min Joung-Ki, Cheongpung Valley 1, Oil on canvas, 130×162cm, 2019

Features that use different perspectives and time zones on screen are concentrated in Cheongpung Valley 1 and Cheongpung Valley 2. As revealed in the titles, these are a series of Inwangsan paintings. What mediates the two is a French building of 1983m2 built by Yun Deokyoung, one of the pro-Japanese group in the Japanese occupation period. In fact, the building was demolished in the 1970s, but the artist still inserted it into the painting describing the present. Thus, we can see how another time zone intersects with a screen, and the re-drawn series of the same landscape highlights this fact all the more. This is to examine how the same scene can look different through Cheongpung Vally 1, describing the scenery surrounding a French-style building, and Cheongpung Vally 2, which contains Cheongwadae, French architecture, and a mountain range. Through landscapes using a variety of timeframes, perspectives, and materials, Min shows what we see can varies depending on the view and context.

In other words, for Min Joung-ki, the scenery is not an emotional scene, but a learning object that scrutinises geographical contexts and a means of exploring the origin of a place. ‘You need to think about things that have been lost and altered’ he says, and aims at understanding the landscape as the work of psychological awareness beyond reproducing the real terrain. The urban landscape quickly becomes familiar and natural, but the landscape paintings that are reproduced through such an undertaking can bring about multi-layered meaning.

Kim Bongryol, a researcher of traditional architecture, proposed ‘imagination from the ruin’ while studying historical buildings whose construction had disappeared but the traces of the site were left behind. It means that one can imagine the essence of architecture through its place, although nothing physically appears. Wouldn't Min's landscapes also look at urban landscapes based on such imagination? It is because the city he paints is a place where so many things happen and so much disappears. We only now look at the present, but the artist looks at the overall context of the landscape in many ways. He, who used to describe the people's lives that once went unnoticed, portrayed another era and perspective that only pays attention to 'the present'.

53