SPACE December2025 (No. 697)

Kang Jungyoon, co-principal of a root architecture, studied architecture at Ewha Womans University and began her professional career at guga urban architecture. In 2015, she co-founded a root architecture with Lee Changkyu—a name inspired by the fundamental tone in music, reflecting their pursuit of architecture’s essential nature and disciplined simplicity. Their practice explores the question of what kind of space best resonates with contemporary life, engaging deeply with time, memory, and place. Representative works include Gosan-jip (2017), Slowboat atelier (2018), Cheongsu Mokwoljae (2022), Woljeong-ri Doojip (2024), and Veke (2024). Extending from architectural research and surveys to public architecture, their work continues to expand the discipline’s scope. They received the Jeju Architecture Awards (Special Prize, 2020) for Gosan-jip, and the Korea Wood Design Awards (Grand and Excellence Prizes, 2023 & 2025) for Cheongsu Mokwoljae and Jeju My Hut (2024). They were named a recipient of the 2025 Korea Young Architect Award. Editor

Exterior view of the intact façade of the Seogwipo Tourist Theater photographed by Park Youngchae ©Park Youngchae

Supporters Gather at the Seogwipo Tourist Theater

It was the 19th of September—early autumn, when cool winds began to replace the fading summer heat. I was about to enjoy a rare, quiet weekend afternoon when a message arrived: ‘Demolition has started. I called for a meeting with the mayor, but it went unanswered. I’m heading to Seogwipo now. I’ll share updates from the site.’ It was from Hyun Gunchul (president, Jeju Special Self-Governing Province Architects Association). In Seogwipo, Kim Jigeon (principal, Atelier Ji) had been closely following the situation, sensing the need to act after talk of demolition appeared in the press, and had requested a meeting with the mayor only a day earlier. Yet, on that quiet weekend morning, demolition began without notice. When I reached the site, fencing had already gone up around the theatre, and the crash of stone walls filled the air. From the courtyard of the Lee Jungseop’s former residence, I began photographing through the trees, while clouds of dust rose with every swing of the orange excavator’s arm. Together with Lee Changkyu (co-principal, a root architecture), I moved to the Olle Trail facing the theatre, slipping my phone through a gap in the fence to capture at least the sound. Earlier arrivals – Hyun Gunchul, Kim Jigeon, and Kang Myoungsuk (principal, Cat Ocean Architects) – were in the site office demanding the demolition be stopped. Because it was the weekend, they couldn’t reach senior officials, and so they pleaded with the on-site supervisor to limit the demolition and preserve the removed stones. By afternoon, others joined—Park Kyungtaek (president, Jeju Chapter of the Korea Institute of Architects), Yang Gun (principal, GAU Architects), Kim Taeil (professor, Jeju National University), Kim Bongchan (principal, The Garden), and Lim Jaeyoung (Jeju bureau chief, NEWSIS). Architects, cultural figures, and journalists from across Jeju converged on the site. Their collective urgency stopped the demolition in its tracks. It was a day when both body and mind raced with tension.

The Seogwipo Tourist Theater was the first modern, purpose-built theatre in Seogwipo. Constructed during the 1950s and 1960s, when concrete architecture began spreading across Jeju, the theatre’s hall and projection room were built in concrete, while the seating and stage areas used Jeju’s traditional dry-stone masonry, giving the building the look of a stone granary.▼1 Its timber truss roof, topped with corrugated metal, realised the hybrid sensibility of maritime culture. Funded by contributions from local citizens, the theatre received its occupancy permit in 1960 and officially opened in 1963. It screened films and hosted school events and concerts, becoming not only a cultural facility but a communal stage for everyday life. An office and storage wing were added in 1982, but after a 1993 fire destroyed the roof, the theatre was ordered to close and left unused. Following more than a decade of abandonment after its 1999 shutdown, the building was revived through the Seogwipo City’s Art Platform project in 2013. With its roof gone, basalt walls weathered by time, and ivy that changed colour with the seasons, the theatre became a special place in the memory of many. After a 2015 renovation, it reopened as an outdoor theatre dedicated to the arts, drawing more than ten thousand visitors each year.▼2 Each spring, Park Jeonggeun (professor, Jeju National University) and Lee Sunmin (principal, CircleTriangleSquare ARCHITECTS) brought first-year students to the theatre to study form and composition. Beneath its ivy-covered walls, both locals and visitors gathered to enjoy lively performances that became part of Seogwipo’s seasonal landscape. The city, which had been using the privately owned theatre rent-free, acquired it in 2022 together with Lee Jungseop’s former residence and walking path nearby—on the condition that ‘the original form of this symbolic space’ be maintained. Seogwipo City then invested 300 million KRW to install a media façade on the theatre’s exterior, continuing programmes such as the artist’s walking tour and outdoor concerts up until this spring.

View of the outdoor theatre of the Seogwipo Tourist Theater prior to demolition photographed by Ko Seongeun (principal, GOGL. ARCHITETS) ©Ko Seongeun

In September 2025, demolition of the Seogwipo Tourist Theater began—without notice. The stated reason was that the neighbouring Lee Jungseop Art Museum project required basement excavation, and the theatre’s unstable structure posed a potential risk. It was, as one architect remarked, like demolishing your neighbour’s house because its foundation might threaten your own. In May, Seogwipo City had urgently commissioned a structural safety inspection, and by August the building was downgraded to grade E. When the city purchased it in 2022, it had been grade C—meaning it deteriorated two levels in less than three years, raising concerns of administrative neglect. Although the Precision Safety Diagnosis Report had first recommended repair and reinforcement for reuse, the city chose the final option – demolition and reconstruction – pushing ahead to what it called ‘swift administration for safety’. Ironically, this very building had been recognised in 2020 by the Jeju Special Self-Governing Province as an architectural asset for its architectural, social, and historical value, and had received an accolade in the Jeju Architecture Awards from the Jeju Chapter of the Korean Institute of Architects (KIA) in 2021. Those who gathered that day, as the basalt walls began to fall, felt they were losing more than a structure—they were losing their own sense of time and memory. Architecture, they believed, is not a facility but a place of remembrance, and once memory collapses, it cannot be rebuilt. That understanding brought everyone together at the site.

On the 22nd of September, after a tense weekend, an urgent meeting was held with Seogwipo City officials. Having reflected on past losses – such as the demolitions of Casa del Agua (2009, architect Ricardo Legorreta) and the Administration Building of Jeju National University (1970, architect Kim Chung-up) – Jeju’s architectural community resolved to unite. The three professional bodies agreed to speak as one. That same day, members of the Jeju Branch of the Korea Institute of Registered Architects (KIRA), the Jeju Chapter of the KIA, and the Jeju Branch of the Architectural Institute of Korea (AIK) gathered before the Seogwipo Tourist Theater, an event that drew strong media attention. Soon after, the three associations released a joint statement titled ‘An Appeal to Preserve Seogwipo Tourist Theater’. The statement urged that policy decisions not be made unilaterally by the authorities but instead be guided by public dialogue towards rational reuse. It called for an immediate policy shift to preserve and regenerate historically, culturally, and architecturally valuable buildings for future generations to share. Support quickly grew. The Jeju Olle board of directors, the Seoul Architecture Forum, and architects and civic groups from across the country issued statements of solidarity. Contributions of reference materials by TechCapsule (principal, Hwang Jieeun) and others added further strength. Alongside talks with the administration, Jeju’s architects recognised the need to engage the wider community. Acting voluntarily, they formed the ‘2060 Seogwipo Tourist Theater TF Team’, working collectively to inform the public, document the theatre’s value, and develop alternative proposals for its preservation and reuse.

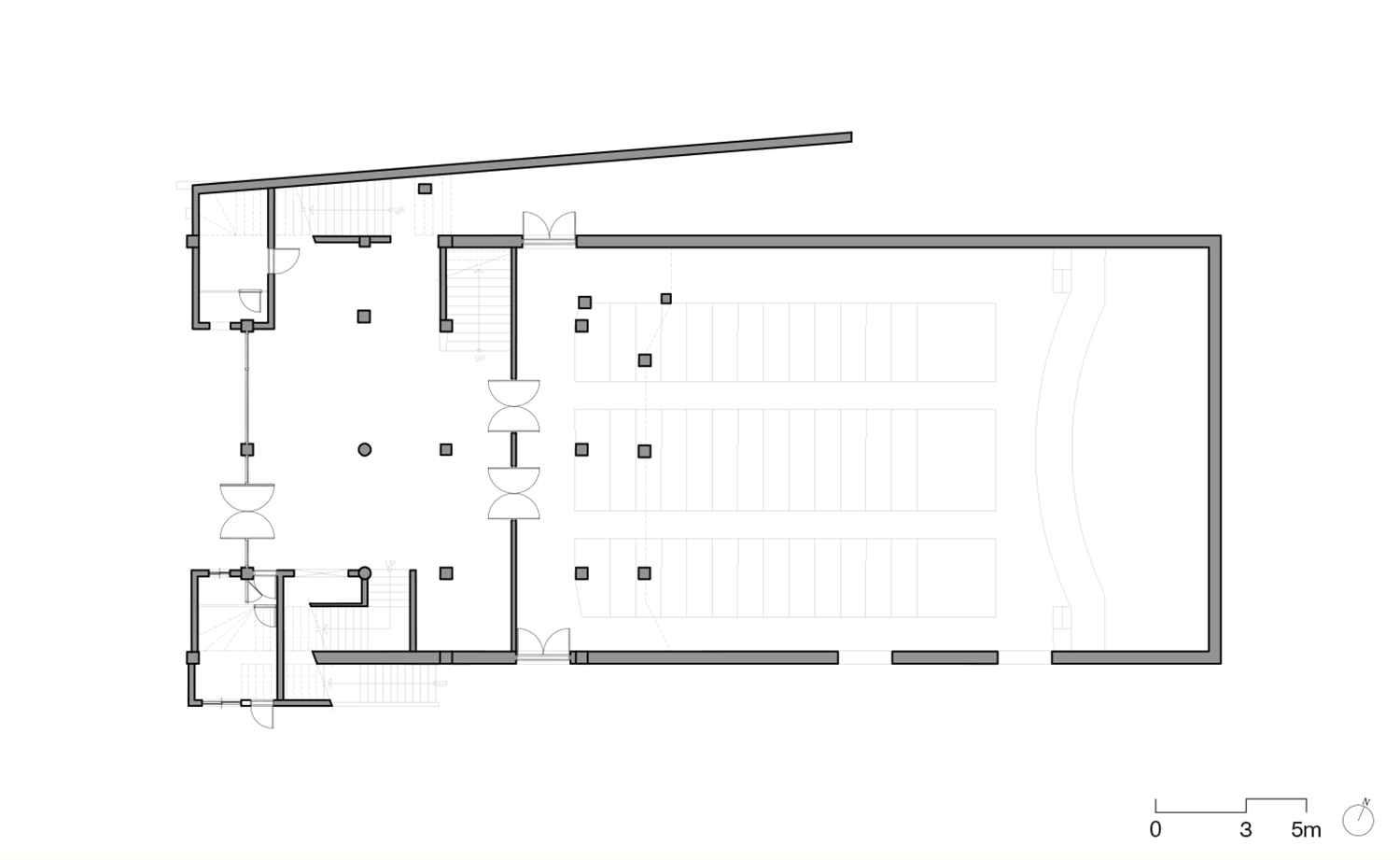

First floor plan of the Seogwipo Tourist Theater drawn by Baek Seunghun (principal, S.O.D.A architects) ©Baek Seunghun

Public Architecture in the Spirit of Sunuleum

When speaking of architectural value, we often imagine distant relics once enjoyed by elites or the celebrated masterpieces of world-famous architects. Yet the architecture of our own modern era – spaces shaped by the people who live and build together – bears meaning no less important. These, too, become history, carrying forward the values of their time.

The Seogwipo Tourist Theater stands on stone walls built in the most fundamental Jeju way: by stacking stones. On this island, stonework is never final—it is a living structure, ready to be dismantled and rebuilt whenever needed.▼3 That ongoing process is part of the architecture itself, a technical and spiritual expression of a culture that accepts imperfection. It mirrors the life of Jeju’s people, who have long adapted to the island’s rough and unpredictable nature by repairing and rebuilding rather than replacing. Jeju architecture, therefore, values process over completion, attitude over form. The making of the theater also reveals the communal spirit known as sunuleum—shared labour that binds people together. Villagers carried, stacked, and set stones side by side, deepening their sense of solidarity through the act of building. The theatre was not the work of one architect but the product of a community and its time. Such a sensibility continues to define Jeju’s architecture: the lyricism of restraint, the detail honed through experience, the unembellished forms that age with quiet dignity. Together they compose a rugged yet serene beauty that is uniquely Jeju.

Even under international criteria, the value of the Seogwipo Tourist Theater is evident. The UNESCO World Heritage framework identifies ‘historical evidence, social memory, architectural and technological evolution, and the interaction between humans and the environment’ as essential values, while ICOMOS defines ‘authenticity’ and ‘integrity’ as the standards of preservation. The theatre embodies all of these: the indigenous technique of basalt stone masonry, the collective memory of performances and gatherings, and the architectural imprint of Jeju’s social and cultural life. It is particularly notable as a rare structure built entirely of stone – approximately 14m wide, 21m long, and nearly 10m high – without embedded columns.▼4 In an era with little mechanised equipment, such a feat – achieved by the hands of local residents and craftsmen – represents the concentrated labour and skill of Jeju’s people. Formed from materials of the island and built by those who lived there, the theatre expresses not just structural ingenuity but also the life and spirit of its makers. When combined with the oral recollections of elders who participated in its construction, the Seogwipo Tourist Theater stands as a living testament to what UNESCO calls ‘the interaction between humans and the environment’.

Partial demolition view of the Seogwipo Tourist Theater photographed by Park Youngchae ©Park Youngchae

From an architect’s perspective, the significance of the Seogwipo Tourist Theater extends beyond its local context to the universal values of place, time, and public life. Its architecture carries the materials, craftsmanship, climate, and patterns of living unique to Jeju, giving the building its deep sense of place. For decades, it has stood in the same spot, connecting generations and shared by countless hands. Such qualities affirm that the theatre is not merely an old, unsafe structure but a modern heritage that embodies the landscape and spirit of its time. The years accumulated within it surpass its physical frame. It is a space marked by touch—where generations overlapped through performances, school festivals, and film screenings. Even after people departed, the traces of those uses remain, etched into the walls and floors, quietly storing the collective memory of those who once gathered there.

The question before us is not how long a building can stand, but how long it can be remembered. Preservation is less about technique than about attitude. When architecture recovers that attitude, a city grows more slowly but with greater depth. Even as its form or function evolves, a building remains alive so long as the time and emotions it holds continue to flow within it. The Seogwipo Tourist Theater still holds that possibility. The discussion we now face – between demolition and preservation – is, ultimately, a beginning: a question of how we choose to carry our memories forward. Interest in the architecture of our recent past is stronger this year than ever before. Project Re\Turning Gunsan (covered in SPACE No. 694) by ISON Architects (principal, Son Jean) has garnered major recognition, including the Korea Space Culture Awards, revealing the possibilities that emerge when the architecture of yesterday meets the life of today. The 25th-anniversary exhibition ‘fiction non fiction’ (refer to pp. 118 – 121) by guga urban architecture (principal, Cho Junggoo) traced the firm’s long pursuit of architectural memory, illuminating how the everyday and the built environment that holds it can be profoundly beautiful. At ‘picnic’ the CAC-curated exhibition ‘The Autobiography of Hilton Seoul’ (covered in SPACE No. 696) offered a gracious farewell to the soon-to-be-demolished Hilton Hotel and its architect Kimm JongSoung (honorary chairman, SAC International), through the voices of architects, artists, and cultural figures. Encouraged by these conversations, Jeju will host a roundtable on the Seogwipo Tourist Theater in November, followed by a forum in December dedicated to the preservation and adaptive reuse of modern architecture.

A line from The Autobiography of Hilton Seoul stays with me: ‘We will be judged not by the monuments we build, but by the ones we destroy.’▼5 The abrupt farewell to a building that had endured the passage of time, a structure we assumed would always stand, mirrors the situation now faced by the Seogwipo Tourist Theater. The difference, however, is that this theatre is not yet gone. If the administration chooses, it can still be preserved, its life extended through thoughtful reuse. How we regard what remains, and how we carry it forward, will reveal much about who we are. Perhaps those of us practicing architecture in Korea today are living in a more critical time than we realise.

_

1 Kang Myoungsuk, ‘Century Project: Seogwipo Tourist Theater’, Journal of Jeju Institute of Registered Architects, 85 (Nov. 2024), p. 6.