SPACE November 2025 (No. 696)

Exhibition view of Nayoungim & Gregory Maass’s section

Exhibition view of featuring works by Oksun Kim, Kim Jipyeong, and Ha Cha Youn at the second floor

The exhibition ‘Undoing Oneself’, which shone a light five mid-career artists (or teams) – Kang Hong-goo, Nayoungim & Gregory Maass, Oksun Kim, Kim Jipyeong, and Ha Cha Youn – was on show at the ARKO Art Center until the 26th of October. ‘Undoing Oneself’ is part of the programme that highlights mid-career artists, a culmination of Arts Council Korea’s Mid-Career Artist Support Project and Artist Research-Study-Critique Support Project. The exhibition explores the paths of these mid-career artists, tracing how they engage in acts of self-critique and self-reference as they articulate their artistic worldview. What does it mean for artists who have achieved their own unique visual language to revisit the past? How does it reveal to move from one’s past self to their present self? SPACE looked into the meaning of such a curatorial strategy and the methodologies that informed this exhibition, which sought to capture the practice and process of an art that oscillates between critique and practice.

Kang Hong-goo, Who am I 10, 1998, digital compositing, digital c-print, 40.5×60cm.

Left: Kang Hong-goo, Fugitive 1, 1996, digital compositing, digital c-print, 126×200cm. Right: Kang Hong-goo, Daikon and Rice Bowl, 1992, mixed media on canvas, 150×180cm.

What is Retrospective, Anachronistic, and Past

When reconstructing the work of artists who have reached a certain point in their trajectory and attained a sense of completion in their own visual language, curators must take a detoured approach. This is because the meaning and narrative weight of the artist and their work often outweighs the logic of the curatorial framework. In this context, the exhibition title ‘Undoing Oneself’ is compelling in that it focuses not on external voices but on the ‘self’. After all, aren’t artists beings who drift and move forward as they oscillate between affirmation and denial? The inner drive to question and transcend a seemingly completed language may sustain their practice, but when this process and period of reflection are formally revealed through an exhibition, deeper consideration of the subject and its expression follows.

From the outset, the exhibition’s preface stated that it ‘focuses on the medium, visual language, and methodology of mid-career artists, tracing their trajectories as they reference or resist historical temporality and renew their practices’. This suggests that despite differences in age and medium, all participating artists are critical figures with narratives of self-subversion. The preface continues by explaining that the transformation of the self through critique and reflection is ‘a crossing of historical time and locating the artist’s coordinated within the magnetic field of contemporary Korean art’. This strategy of meta-critique, grounded in critique, is concretised through ‘Correspondence’, a collection of dialogues between curators and artists during the planning process.

The ‘Correspondence’ display on the exhibition hall bench

Against the Self: The Inevitability of Self-Subversion

Spanning the first and second floors, the exhibition opens with works by Kang Hong-goo. Though he majored in painting, Kang has used photography – through compositing images and painting over photos – to expose the absurdities and contradictions of reality. At the entrance, two representative works are juxtaposed: Who am I 10 (1998), which composites his face and sunglasses onto characters from Quentin Tarantino’s film Reservoir Dogs (1992), and Who am I 16 (1998), which overlays his face onto a postcard of the Hangang River, depicting himself drowning. These works were part of his second solo exhibition ‘Position, Snob, Fake’ (1999), which critiqued the harmful consequences of capitalism and the politics acting only for the show. The former anticipates deepfake techniques, while the latter expresses the struggle of living as an artist in Seoul. His images ‘disguised’ as a photograph which deviate from pure photographic grammar, function as media that reveal ‘concealed realities’ through a gaze that defamiliarises everyday life—such as the fear of war in a divided nation or leisure scenes stemming from capitalism. His message, which twists properties of the media and reveals unreasonable aspects present in contemporary society, aligns with the preface of that solo exhibition declaring that ‘an artist is one who doubts life.’ It is at this point that his satirical stance, even describing himself as a ‘B-grade artist’, stands out. New works originally created through Photoshop and AI technologies – Dinosaur (2024), Balloon (2024), and Self-Portrait (2025) – are also displayed, seamlessly connects with his earlier works thanks to either the current society where fabricated imagery manifests, or to the message which penetrates the era.

Situated across Kang’s works, a beige-toned space features the works of Nayoungim & Gregory Maass. Their strategy involves recomposing obsolete objects and past events into new contexts and relationships. Their cross-media practice – painting, sculpture, installation, and publishing – embraces both tangible and intangible knowledge, space, and systems. Despite being Korean and German, they communicate in French, a third language, sometimes using the relational dynamics of conversation as a conceptual basis for their works. They also created a virtual platform Kim Kim Gallery (2008 –), which questions conventional exhibition formats and the art world’s economic structures. This exhibition is based on their artist book Diarrhea: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment (2025), which plays on the dual meaning of ‘diarrhea’ and ‘diary’. The ten concepts that appear in this book, which organises thoughts that cross the boundaries of different cultures, knowledge, systems, and daily life, were reconstructed and presented as an installation work 10 sleazy Pieces (2025). Their practice of mimicking, transforming, and rearranging existing works and historical references reflects the book’s phrase ‘I will be/am somebody else today,’ showing how both artist and artwork resist fixity and renew themselves through ongoing flows of thought and working methodologies.

Ha Cha Youn, Ich bin Künstlerin, 1999, inkjet print on adhesive sheet, bedding, photo: 98×62cm. The space in which the work is installed is Ha Cha Youn, Jjockbang, 2013 (reproduction in 2025), mixed media, variable dimensions.

Ha Cha Youn, Sweet Home, 2004, single channel video, colour, sound, 2 min 29 sec.

Settlement and Migration, Discrimination and Exclusion, Betrayal and Renewal

The second floor of the exhibition features works by Oksun Kim, Kim Jipyeong, and Ha Cha Youn. Oksun Kim, who moves between Jeju and Seoul, focuses her photographic work on Asian women, hybrid outsiders, and nature. In this exhibition, she presents a new large-scale wall installation titled large stream atlas (1962 – 2025), which combines her previous photography works with new photographs. This work, which juxtaposes old family photos, images of women in international marriages, and intercultural youth, goes beyond personal narratives and reveals the artist’s will and process of seeking out and connecting with people in similar circumstances. This message is expanded upon in her two-channel video Home (2023), which documents her journey to Japan to interview three women, including a second-generation Zainichi Korean, a Korean woman residing in Japan, and a marriage migrant. The shift from photography to video reflects a necessary evolution in medium, allowing her to narrow the distance between subject and viewer and more fully convey the interviewees’ stories.

In front of Kim’s work stands a wooden structure resembling partitioned rooms, a recreation of Ha Cha Youn’s work Jjockbang (a term for tiny rooms, 2013). After studying in France and working between Korea and Europe, Ha has focused on the theme of ‘localisation’ – the struggle experienced by migrants and immigrants to find a place to settle. She highlights the plight of those forced to repeatedly relocate due to government policies: migrants, immigrants, the homeless, and refugees (including herself). For them, the act of securing a small space to lie down – what she calls ‘nesting’ – is a fight for survival. Her video Sweet Home (2004), shown on a small TV screen in Jjockbang, captures her laying down styrofoam on a bench of Paris subway platform to create a sleeping space, defying the reality of benches designed to prevent the homeless from lying down. Another video, Yeongdeungpo (2013), metaphorically represents those pushed to the margins of the city. Having once lived in Yeongdeungpo, the artist wandered through its jjockbang village, imagining what it would be like to live there, and filmed the result. Without showing faces, the camera angle remains low, following a protagonist who pulls a small cart, collecting empty flower pots and discarded household items, constantly moving and pausing within the village.

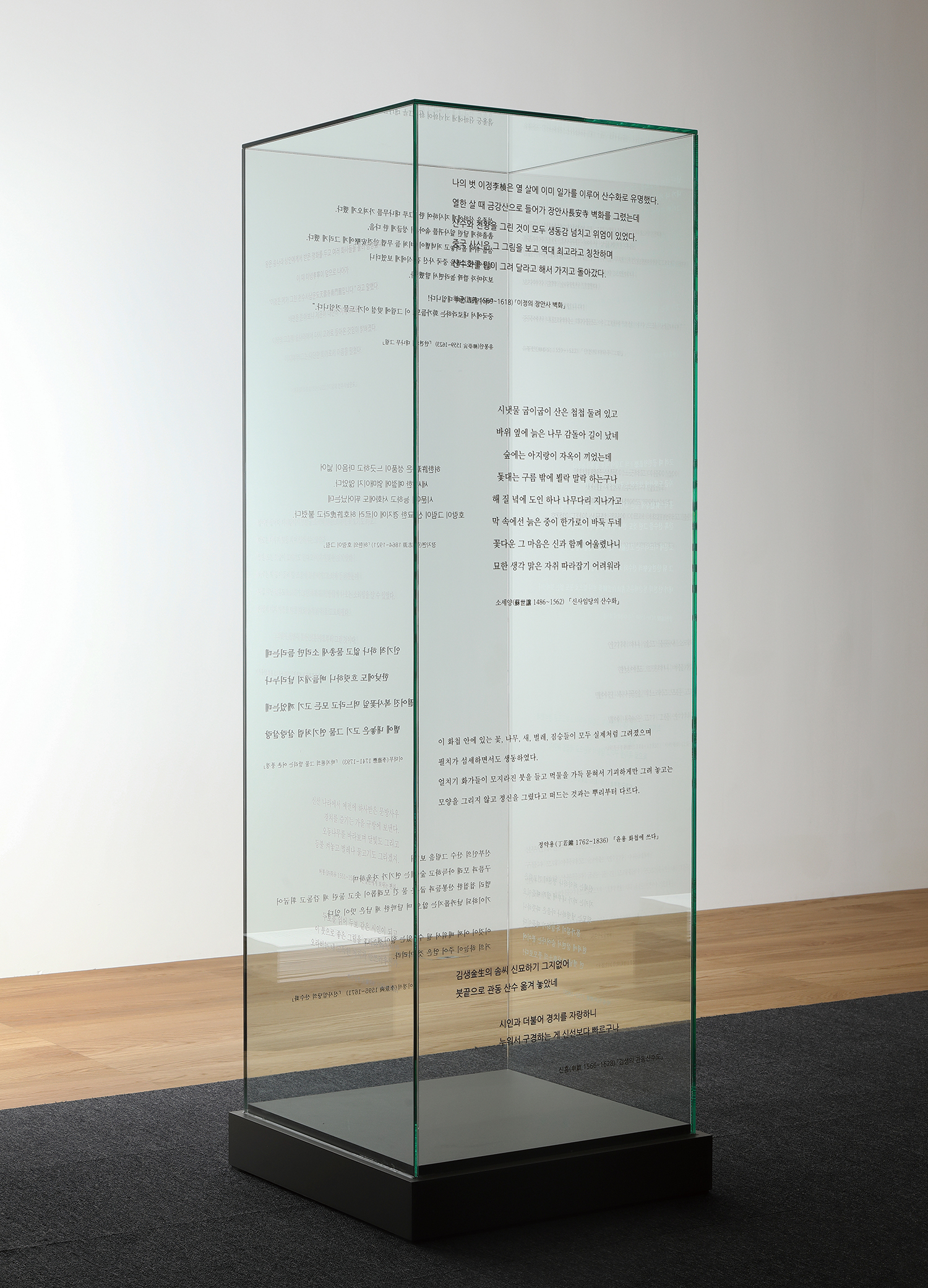

While Kim and Ha focus on themes of migration, settlement, and identity – delving into the stories of those denied and excluded – Kim Jipyeong turns his attention to traditions marginalised within the dominant discourses of art history, literature, and mainstream Eastern-style paintings. Trained in Eastern-style painting, she challenges and reinterprets established traditions (materials, subjects, methodologies) to create new traditions. She paints folding screens using red pigment traditionally reserved for talismans, and features women, animals, and mythical figures rarely seen in Eastern-style painting as main characters, and depicts animals liberated from humans enjoying freedom. Her attempt to redefine and expand the meaning of tradition through continual self-renewal is most clearly seen in Paintings Lost (2021), placed at the centre of the exhibition. This work records texts describing legendary but non-existent paintings, such as Lee Nyeong’s Cheonsusanammundo from the Goryeo Dynasty, on the surface of a large glass case. The irony of describing a painting that doesn’t exist highlights the absence of tradition today. Rather than trying to fill this void, the artist reminds us of the potential for tradition to exist through reinterpretation, renewal, and subversion.

Kim Jipyeong, Paintings Lost, 2021, silkscreen on glass box, 60×60×190cm.

The Contemporary Characteristics of the Artist and their Artwork

For artists, early or past works remain fossilised in memory unless they are continuously exposed or summoned by others. This is due to the fact that works are completed within the specific spatial and temporal context in which they were conceived, created, and exhibited. What meaning can be generated by re-reading the self or the contexts from that time? Furthermore, how can the past remain relevant ‘here and now’?

This process of reflection and forming relationships with the present can be explored through ‘Correspondence’. The motivations behind embarking on a work, the reasons for choosing and expanding a medium, the strategies for re-presenting past works to create new layers of meaning, and considerations for future projects are all articulated in concrete language through dialogues that oscillate between self-statement and self-critique.

For example, Kang Hong-goo explains his shift from painting to photography by saying that for him, painting as a medium with historically dense layers of meaning felt like ‘hitting a high wall, leading him to choose computer-based work as a form of escape or avoidance’. Reflecting on the time when he created Who am I series he recalls the 1990s as a period when ‘young artists emerged with more personal and less formal work, infused with postmodern, socially critical, and political elements, situated between the abstraction of monochrome painting and the contrasting style of public art.’ This helped him reaffirm his position within the contemporary flow of Korean art.

Left: Kim Jipyeong, The World Spins, 2023, mixed pigment, gold leaf and silver foil on hanji, 160×130cm. Right: Kim Jipyeong, Without Fears, 2022, muk, gold leaf and mixed pigment on lacquered hanji, 148×105cm.

‘The exhibition ‘Position, Snob, Fake’ held at Kumho Museum of Art in 1999 was a summary of the societal conditions I witnessed and experienced at the time. ‘Position’ referred to Korea’s geopolitical situation, division, and questions about where I stood and what I was doing as an artist. ‘Snob’ diagnosed the snobbish desires I had as an artist, along with the inescapable snobbery of society as a whole. And ‘fake’ stemmed from my suspicion that all images dominating the world, including those I created, and the lives people led were, in fact, fake. Even now, these three words remain at the core of my work. Nearly 30 years have passed, but ‘position’, ‘snob’, and ‘fake’ continue to grow in influence and dominate the world.’ _Excerpted from the ‘Correspondence’ with Kang Hong-goo

Oksun Kim, Home, 2023, two channel video, colour, sound, 15 min.

This relational dialogue and self-critique extend beyond the artists and their works to institutions. Some of the participating artists were featured in ARKO Art Center’s ‘The New Generational Tendency in Korea Contemporary Art’ exhibitions held between 1992 and 2003. Kang Hong-goo participated in ‘Frame or Time—From Photography’ (1998), Nayoungim in ‘Mixer & Juicer’ (1999), and Oksun Kim in ‘Paradise Within Us’ (2002). In this exhibition, Kang’s part of Seashore Resort series and Nayoungim’s Legends reappear, re-calling artists once labeled as emerging talents 20 – 30 years ago as mid-career artists. This re-contextualisation attempts a meta-critique of the institutional production of criticism.

In a ‘Correspondence’ with Nayoungim, the curator reflects that in 1999, ‘the participating artists presented works that addressed their positions as artists and their interventions in institutional structures, revealing the diverse visual languages of 2000s visual art.’ The curator adds that the artists’ critical awareness of the mechanisms and systems surrounding art (in Nayoungim’s case) have led to the creation of Kim Kim Gallery.

However, the multilayered network of relationships captured in ‘Correspondence’ was unfortunately presented rather passively in the exhibition space—only as printed materials placed on benches and walls, without physical integration with the artworks. While this may have been intended to prevent the dialogue from overshadowing the works themselves, expecting visitors to sit and read over ten pages of letters per artist is a tall order. Nevertheless, the exhibition proved to be a compelling site for discovering the signs of an era when interest in auto-theory is growing, and where layers of meaning are expanded through the act of critiquing and renewing oneself. One hopes for more opportunities to explore the struggles and challenges of mid-career artists who work at a slow, deliberate rhythm rather than chasing fast-moving trends.

Exhibition view of Kim Jipyeong’s section

Oksun Kim, large stream atlas, 1962 – 2025, archival pigment print, digital c-print, variable dimensions (out of a total of 31 photographs, 28).