SPACE August 2025 (No. 693)

Installation views of DeafSpace: Double Circles. Visitors can engage in visual communication without facing others directly, thanks to translucent walls and mirrors.

Barrier-free, universal design—these are the policies that often come to mind when discussing ‘disability and architecture’. Yet environmental difficulties remain in the everyday lives of disabled people. Clearly, the systems in place require improvement and reinforcement. But is this enough to simply create better policies? David Gissen and Richard Dougherty – respectively an architectural scholar who uses a wheelchair as umputee, a Deaf architect – respond with a clear ‘no.’ They argue that architecture ‘for’ disabled people, created through regulations applied only ‘after’ design, is insufficient. Instead, the perspectives of disabled people must be embedded from the earliest stages and the discourse addressed even before design begins. What more can we do beyond improving physical accessibility? What does architecture shaped by disabled perspectives look like? Let’s explore the following proposals and accounts presented by Gissen and Dougherty in ‘Looking After Each Other’, an exhibition held at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) Seoul in Korea.

Interview David Gissen professor, Yale University, Richard Dougherty director, Richard Lyndon Design × Kim Bokyoung

Kim Bokyoung (Kim): Could you briefly introduce the work you presented as part of ‘Looking After Each Other’?

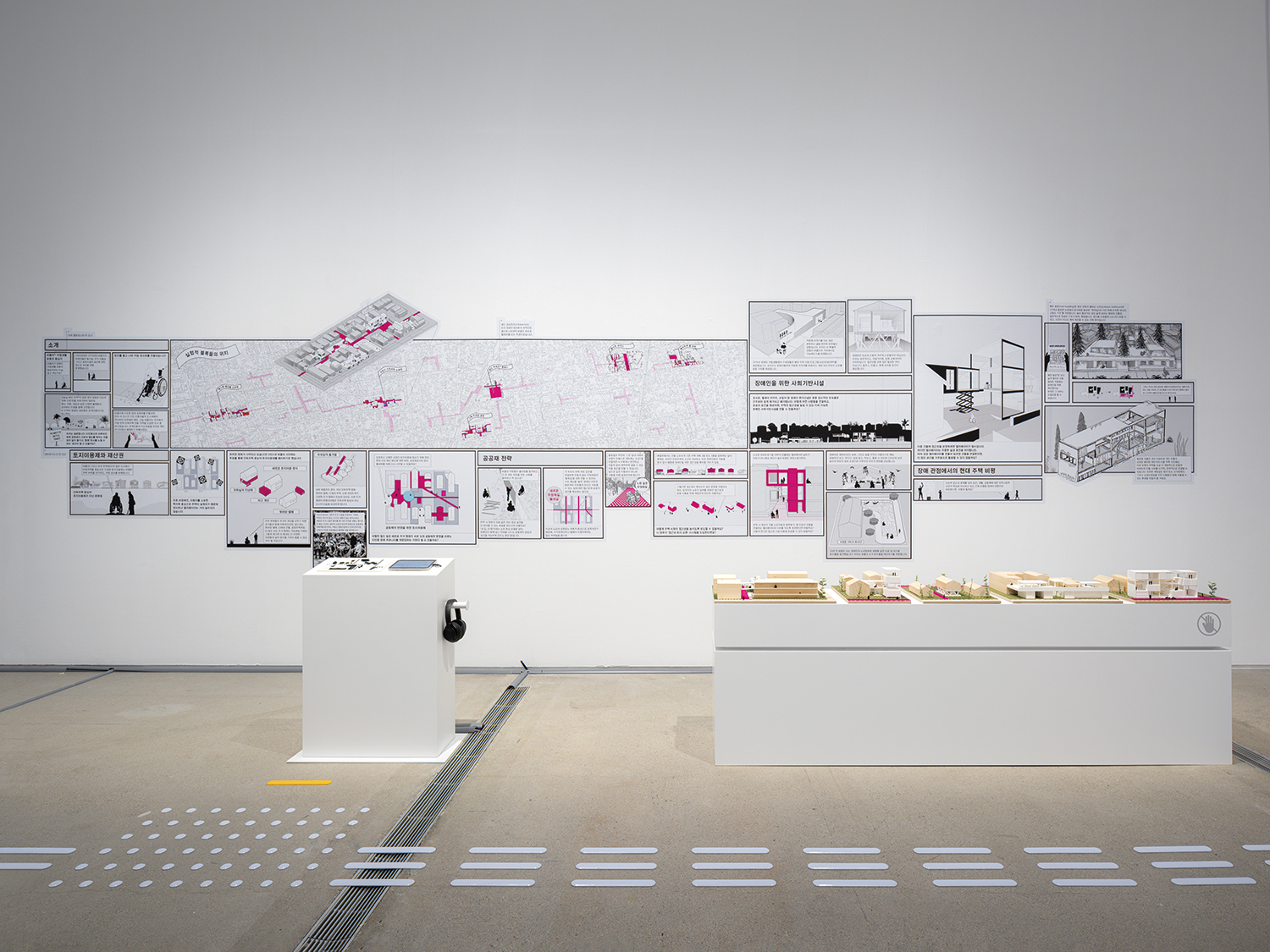

David Gissen (Gissen): We exhibited our proposal for a neighbourhood in Berkeley, California, entitled ‘Block Party: From Independent Living to Disability Communalism’. The project reimagines a single block from the perspective of disability and housing justice. These latter terms describe different political frameworks that agitate for greater equality in the use and ownership of private and public spaces.

Richard Dougherty (Dougherty): Our proposals for the exhibition are centred on the lived knowledge and experiences of disabled people, using the narrative of difference as a creative and generative force in the design process. By adopting design principles that prioritise human connection, our exhibition proposals attempt to offer a radical reframing—viewing disability not as a loss, but as an advantage: a different and remarkable way of being. Our DeafSpace: Double Circles serves as a metaphor for a Deaf family home that embodies these specific design principles representing the different ways in which Deaf people occupy and navigate their spatial surroundings. The outer circle of two concentric circles offers a liminal threshold that acts as an interstitial passage between the space outside the exhibition (Hearing world) and the more sacred space inside (Deaf world). The five colour-coded cylindrical elements are ‘social infrastructures’, which provide a place for visitors to rest personal belongings, freeing both hands for sign language. In the context of today’s digital age where we are facing a decline in face-to-face communication, the DeafSpace: Kissing Chairs installation at the museum’s entrance steps intends to evoke the visual and analogue orientation of Deaf culture, where eye contact is central to conversation. The installation encourages strangers to come together and engage in face-to-face interaction, but it also invites the disabled and non-disabled to enter the museum via the ramp rather than the entrance steps creating more equitable access for all.

Installation view of DeafSpace: Kissing Chair

Kim: What is DeafSpace, and how are these principles reflected in Double Circles?

Dougherty: DeafSpace is simply an approach that prioritises the lived experience and sensory perception of the built environment. DeafSpace was formally documented by the DeafSpace Project (DSP) at Gallaudet University—the world’s only university designed specifically for Deaf and hard-of-hearing students. It focuses on how individuals experience and interact with spaces, emphasising the emotional and visceral connections formed through light, materials, textures, and other spatial qualities. This approach moves beyond purely functional or formal considerations to create spaces that resonate with human presence and evoke meaningful encounters and connections. We were particularly interested in Double Circles’ transitional zone as a space that explores identity, difference, and duality, as well as past and present, inclusion and exclusion, inside and outside. The blurred boundaries are physically represented through the use of translucent walls and mirrors, offering full visual connectivity from every angle; this is an essential aspect of Deaf culture, where visual access is key to communication and inclusion. Although DeafSpace design was initially conceived with the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community in mind, its principles are increasingly being embraced as best practice in urban design. These environments foster connection, improve accessibility, and ultimately bring people closer together.

Kim: You have long been a leading figure in incorporating DeafSpace principles into architecture. How do you apply these principles in architectural practice, and have you faced any challenges when implementing them?

Dougherty: One of our recent projects is Heathlands Deaf School (2024). A critical part of the DeafSpace approach is the prioritisation of user involvement from the very beginning of the design process. Initially, the client team was hesitant about the level of time and resources we proposed to invest at this early stage. However, as they began to see the tangible benefits of our iterative process, their perspective shifted and they became strong advocates for the approach. Before design work began, we engaged staff and students in a series of workshops to gain a deep understanding of their needs, behaviours, and the specific context in which they live and learn. Most of the students at Heathlands Deaf School have additional sensory needs, including visual and neurological differences, therefore we had to ensure the new building could accommodate a broad spectrum of sensory experiences. As a result, we adopted a deliberately phenomenological design approach informed by the following aims: minimising glare and harsh contrasts by introducing diffused lighting from multiple angles; selecting NVHR (natural ventilation heat recovery) systems that reduce background noise; choosing wall colours that enhance the visibility of different skin tones; designing classroom layouts to support a horseshoe arrangement so all students can see each other and no one is isolated at the back; creating liminal or transitional spaces that encourage spontaneous interaction and a sense of belonging. At Gallaudet University, we are currently leading several pioneering projects that reflect inclusive design at every scale even beyond the campus itself. One example is in Washington, D.C.’s nearby NoMa neighbourhood, where developers are beginning to integrate DeafSpace principles into their public realm projects. After their initial resistance with incorporating DeafSpace principles in public realm works, they became to recognise the broader value and benefits of these principles, not just for Deaf users, but for everyone.

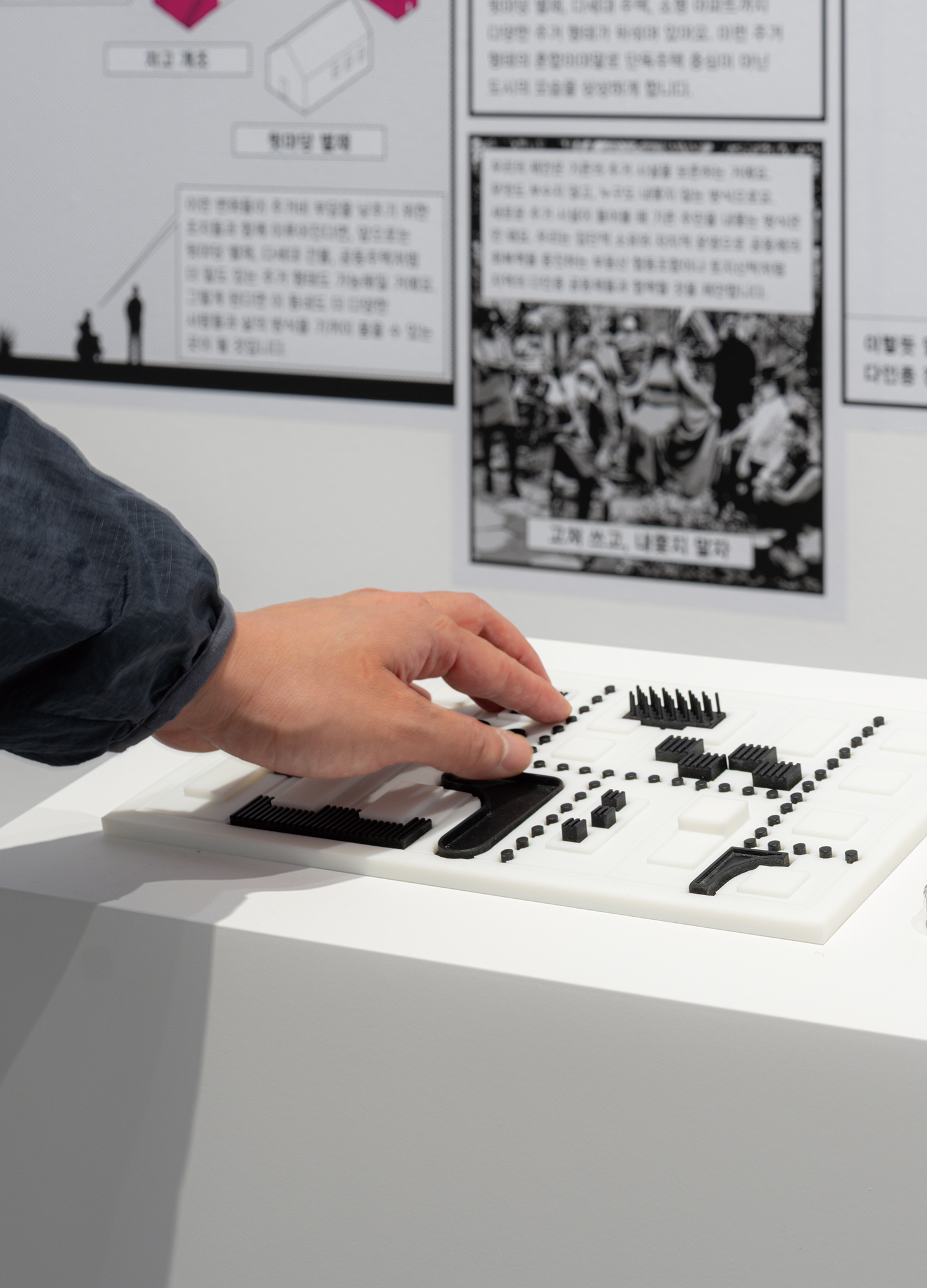

As part of Block Party: From Independent Living to Disability Communalism, a tactile model – initially created to collaborate with a blind team member – offers gallery visitors an additional means to access the project’s architectural and urban strategies.

Inside DeafSpace: Double Circles

Kim: Block Party is closely tied to the concept of an ‘urbanisation of impairment’ which was introduced in your recent book, Architecture of Disability: Buildings, Cities, and Landscapes beyond Access (2022). What exactly is meant by the ‘urbanisation of impairment’, and how is this concept applied across your project?

Gissen: My book was released a few years after we completed Block Party, so the book presents a more thorough vision of that specific idea. The ‘urbanisation of impairment’ describes an approach that seeks to reimagine the entire city and its development through the perspective of disability. For example, many cities are built around modern concepts such as circulation, development, monumentality and visibility, but I offer a critical assessment of these values. I try to imagine what a city might be that lacks these qualities and how that might be beneficial for disabled residents of them. So, how can we imagine the ways that immobility, stasis, and occlusion can become positive values through which to design and build future urban experiences. This is something I am exploring with a new team of collaborators for the upcoming Chicago Architecture Biennial.

Kim: Another core concept explored in Block Party is the ‘a disability critique of property’. Could you explain this concept?

Gissen: The disability critique of property shifts a focus in disability activism away from improving the accessibility of built physical space. Historically, the architecture of the United States shaped and gave form to these ideas about property. I explore how inherent aspects of property – the right to exclude and improve – tend to alienate disabled people and make space inherently inaccessible. In the United States, this quality of property works in at least two ways: One, property tends to put limits on the physical activities of all but its owners (think of the right against trespass, among other issues); and two, in the United States one needs to demonstrate one’s competencies to continue ownership and control over one’s property. When one is deemed incapacitated – mentally or physically – it threatens one’s ability to maintain ownership and determination over one’s property (including one’s own body). As far as I know, I am one of the only people exploring this problem, and in this way. But I hope to develop the concept with others in the future.

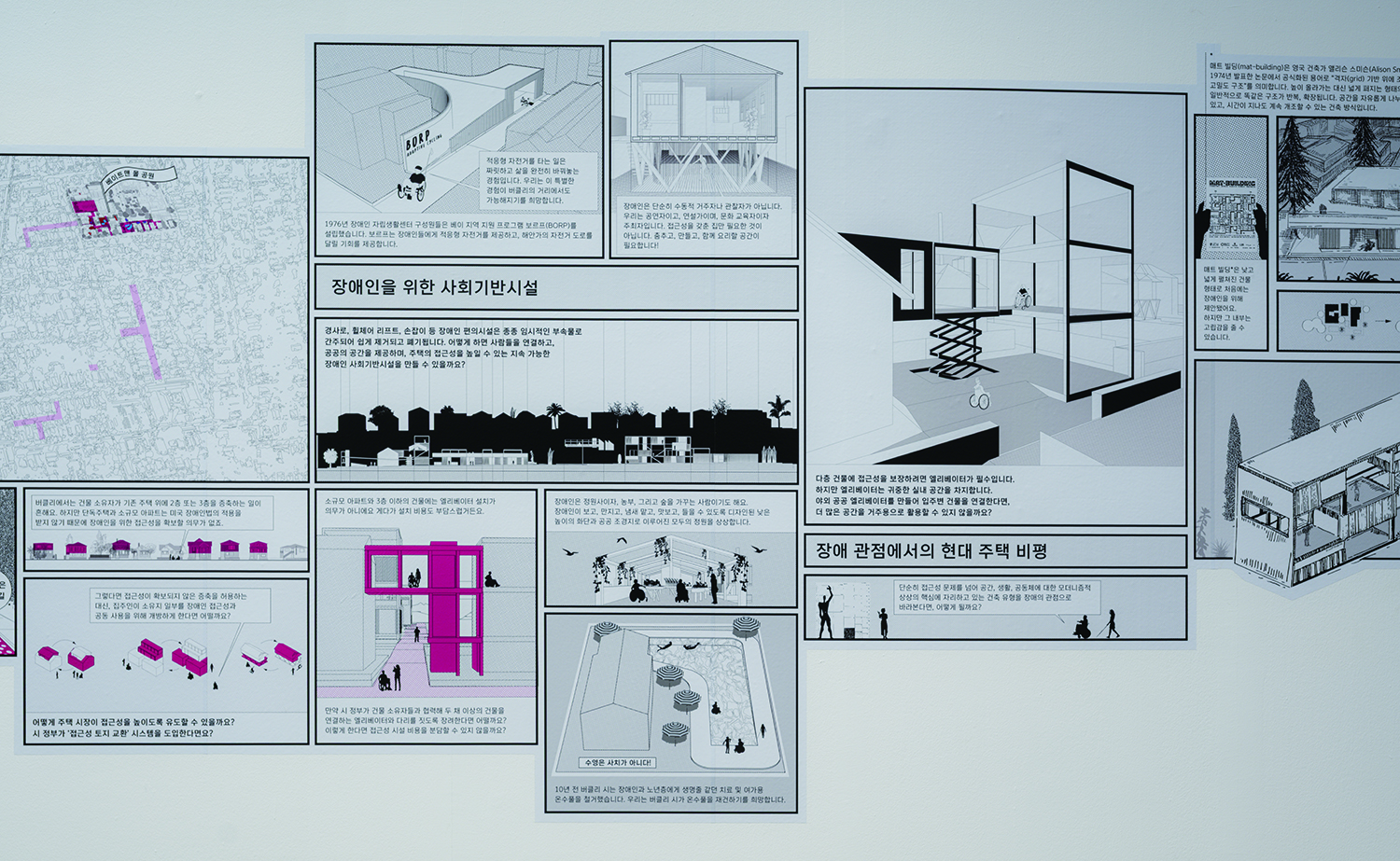

Model of Prince Street Block in South Berkeley, illustrating how the Block Party team reimagines property ownership, urban circulation, housing, and communal space within the neighbourhood. A proposed, accessible pathway – ‘The Meander’ – is shown in magenta felt. The Meander is a proposal that to create a new, accessible slow street – roadways that the city has limited to pedestrian traffic – borrowing rear setback areas of private lots. The white building models in the photo represent the proposal for a mat building—one that enables more practical, flexible, and interconnected living across the block’s existing structures, apartments, and open spaces. (Mat buildings are low, sprawling buildings that were first proposed for disabled people. But their interiors can fell isolating, so team offers a new reinterpretation.)

Drawing of the Block Party team’s proposal. The section shown in the image proposes that the city incentivise property owners to team up and construct elevators and bridges that span two or more small buildings – which are not required by law to have elevators – so that the cost of new accessibility infrastructure can be shared.

Kim: As disabled individuals, you have been critical of this narrow focus—disability in architecture is still predominantly framed around the concept of accessibility. What are the limitations of this perspective, and how can we move beyond it to understand and practise the relationship between disability and architecture in new ways?

Gissen: As previously stated, I critically assess the modern concepts that have shaped many cities. The approach that improves accessibility rather contains these modern concepts. Also, the demand for universal access is based on a Berkeley-style approach spreaded by World Institute on Disability, established by the U.S. disability activist Ed Roberts with a small group of people in the late 1970s and early 1980s. They were anti-institutional, and emphasised personal independence and access. Rather I think we need a plurality of approaches beyond a sole focus on the problems of access and independence. When Roberts was spreading his ideas, some groups resisted and protested his singular approach. For example, when Roberts presented his ideas in Japan, the Green Lawn movement argued that he was like a colonial-era missionary. Among their ideas, they believed that institutionalisation was ok, as long as disability institutions were controlled and managed by disabled people and were very, very small (no more than a dozen residents). They believed that Japanese disability movements needed to develop a politics of the city that differed from the U.S. examples. I think many of the examples I’ve provided begin to outline how we might move beyond accessibility to reimagine the relationship between disability and architecture, but let me give one additional example. I think that we need to explore ways to make construction less physically intense. This entails rethinking how buildings are constructed, the aesthetics of intense construction systems some architects favour, and other ways to reimagine building as a less physically demanding and precarious profession.

Dougherty: Each space should have its own narrative. Yet, as a disabled architect, I’ve frequently observed how the profession often reduces accessibility to a bureaucratic checklist—treating inclusivity as an afterthought rather than an integral part of the design process. In contrast, the DeafSpace approach offers a profoundly human-centred philosophy, embedding considerations of empathy, occupation and aesthetics from the outset. By applying DeafSpace principles, architects challenge the traditional ideals of ‘architectural purity’. This approach reimagines design not just in terms of accessibility, but as a means to create richer, more immersive sensory experiences. There is a pressing need to foster greater awareness of the value of diversity and difference in our built environment. Gallaudet University, for instance, sits at the heart of a cultural shift known as ‘Deaf Gain’, a concept that reframes deafness not as a loss, but as a source of unique cognitive, creative, and cultural contributions to society. This shift urges us to adopt a biocultural lens—one that values difference over conformity. History offers powerful lessons: as the Irish Potato Famine shows, biodiversity is essential to the health of ecosystems. Just as biodiversity, social vitality depends on the presence of diverse cultures, languages, bodies, and ways of thinking. What is often framed as a biological limitation – such as disability – can, in fact, be a social and creative asset that protects against the dangers of monocultural uniformity.

Richard Dougherty, speaking at Seoul Box, MMCA Seoul, as part of the public programme for ‘Looking After Each Other’

Heathlands Deaf School (2024) ©Rachel Ferriman

Kim: To expand beyond accessibility and build a more nuanced discourse around disability and architecture, it seems essential to have more disabled architects. In what aspects should architectural education change to foster disabled architects?

Dougherty: There needs to be a paradigm shift to allow a greater representation of under-represented groups including disabled people into construction and architecture. Representation of diverse minority groups is essential; it brings forth a richer array of human experiences and perspectives. When individuals with diverse needs and backgrounds are involved in the design process, their unique insights can meaningfully inform the outcome. And that change needs to start with the architectural schools. Current systemic and educational barriers prevent many talented and capable disabled designers from entering and thriving in the field. Whilst I was fortunate to benefit from the right support to complete my architectural education, too many of my deaf peers were not afforded the same level of access. I can count on one hand the number of culturally Deaf architects I know, which is puzzling and perplexing given how Deaf people communicate in a very visual language—much like the language of architecture itself. In fact, I’ve often argued that sign language may be even more suited than spoken language for expressing architectural concepts. And yet they are not afforded the same level of access or representation as their hearing peers. Gallaudet University, with its exceptional accessibility, is uniquely positioned to close the attainment gap. As part of this mission, the university recently launched its first human-centered design course, and it’s already proving to be a great success while students are engaging in real-world design challenges.

Gissen: We need to begin with the schools. Most of the elite architecture schools in the United States (which have a disproportionate influence on the profession and academia) are only partially accessible to disabled students. I have been to many of these as a student or professor, so I can confirm this first-hand. Additionally, we need to develop forms of pedagogy and training that are more flexible to student needs and capacities. When I was beginning my teaching career, many women who wanted to become pregnant and raise children (either on their own or with others) instituted significant changes into the professional culture of architecture. Disabled people might continue this work and make demands for professional changes that support their particular needs.

Installation view of Block Party