SPACE July 2025 (No. 692)

Manameh Pavilion by Rashid Bin Shabib and others / ©Marco Zorzanello

‘Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.’: 2025 Venice Biennale | Main Exhibition

The theme proposed by curator Carlo Ratti for the 2025 Venice Biennale is ‘Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.’ He argues that if the architecture of the ‘primitive hut’, designed to ‘respond’ to nature’s threats, has moved towards ‘mitigation’ in the era of the climate crisis, then today, when environmental crisis is a decisive point for us all, it is time for architecture to demonstrate ‘adaptation’ to the environment. This means we need to prioritise not only designs that reduce environmental impact, but achieve fundamentally different design methods. He introduces this new way of thinking by dividing the theme into ‘Natural Intelligence’, ‘Artificial Intelligence’, and ‘Collective Intelligence’, and he emphasises architecture-centred optimism and collaboration across generations, disciplines, and fields of expertise. This inclusive manner is evident not only in the exhibits, but also in the curatorial methods and practices as a whole. Ratti organised the main exhibition, featuring over 750 participants and around 300 works, through an open call. He also collaborated with Arup, a structural engineering firm, to draft ‘A Circular Economy Manifesto’ to ensure the Biennale’s sustainability. During the exhibition, there will also be a programme of talks called ‘GENS’ featuring figures from various fields, such as design and film. This helps to explain why the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement was awarded to Donna Haraway, not an architect but a biologist and feminist. With this as background to our line of questioning, let us explore the main exhibition.

SpaceSuits.Us: A Case for Ultra Thin Adjustments by Emily Ezquerro, Charles Kim and others / ©Luca Capuano

First, Why Donna Haraway?

The aim of this Biennale was to break down the boundaries between different disciplines, as it showcased the work of not only architects but also experts from diverse fields, including DJs, chefs, and Nobel Prize winners. The thinker who best represents this way of thinking is Haraway. Haraway’s way of thinking, which can be explained as a ‘cat’s cradle’, twists and traverses biology, technological science, and feminism, breaking through their perceived disciplinary boundaries with an amusing imagination. Her 1985 writing ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’ is a prime example of this approach, presenting ‘Cyborg’ as a post-human concept that has shattered the dichotomies between nature and culture, organism and machine, and human and non-human. Without despising or idolising science, she focuses on beings that are neither human, machine, nor animal, and she uses language to explain that one realm can no longer conceive or generate the other. The MIT Senseable City Lab, directed by Ratti, also pursues omni-disciplinary thinking. This involves not only connecting different disciplines, but also nullifying the distinction between them, and even goes beyond to ultimately become fused together.

The Golden Lion-winning Canal Café shares a similar approach to this way of thinking. Originally conceived for the 2008 Venice Biennale but unrealised due to various circumstances, the project involved architects, the 2008 Venice Biennale’s curator, and chefs collaborating to purify Venice’s lagoon and create ‘the best espresso’. Not only does it connect the past and present, architects and chefs, and nature and humans in the design process, but its jovial nature, seemingly originating from casual conversation, distinguishes it from retro-futuristic works based on future imaginings from the past. However, when we recall that Haraway’s ‘Cyborg’ is not a concept for a specific being, the fact that the Canal Café is still a work intended for humans takes on greater significance. It is at this moment that we become aware of the limitations of the medium as architectural ‘building’, which is a physical form and difficult to escape from human-centred ideas.

Ancient Future by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and others / ©Andrea Avezzù

Second, Is An Open Call Valid for An Exhibition?

An open call has an open network structure. It is also an experiment in organising an architectural exhibition on a network basis, realising collective intelligence and breaking away from authoritative curation. Consequently, more Korean teams than in previous years were given the opportunity to participate, including IVAAIU City, HAENGLIM ARCHITECTURE & ENGINEERING, and PRAUD. However, many critics pointed out the absence of a guiding curatorial approach. The theme was broad, the number of works was high, and the selection process was deemed inadequate. This was mainly due to the excessive viewing time, which ultimately made it difficult to see or understand connections between one section and another and one work to another, resulting in an environment in which it was difficult to look at each work in detail. In order to find these connections, interpreters must gather their ‘collective intelligence’. However, it is noteworthy that the individual works were created through crossdisciplinary collaboration, bringing it one step closer to practical feasibility. For instance, IVAAIU City’s Lunar Ark began with the idea of building a data centre on the moon. With the assistance of Hyundai Motors Group ZER01NE, and Korea Aerospace Research Institute, the project developed practical plans, such as a robot construction system and a laser data communication system, incorporating suitable materials and unit sizes tailored to the lunar environment. Perhaps, then, the open call is more significant for its suggested methodology of a network-based structure than for the curatorial outcome itself.

CO-POIESIS by Philip F. Yuan, He Bin / ©Luca Capuano

Third, Where Is Optimism in Architecture and Where Will It Lead?

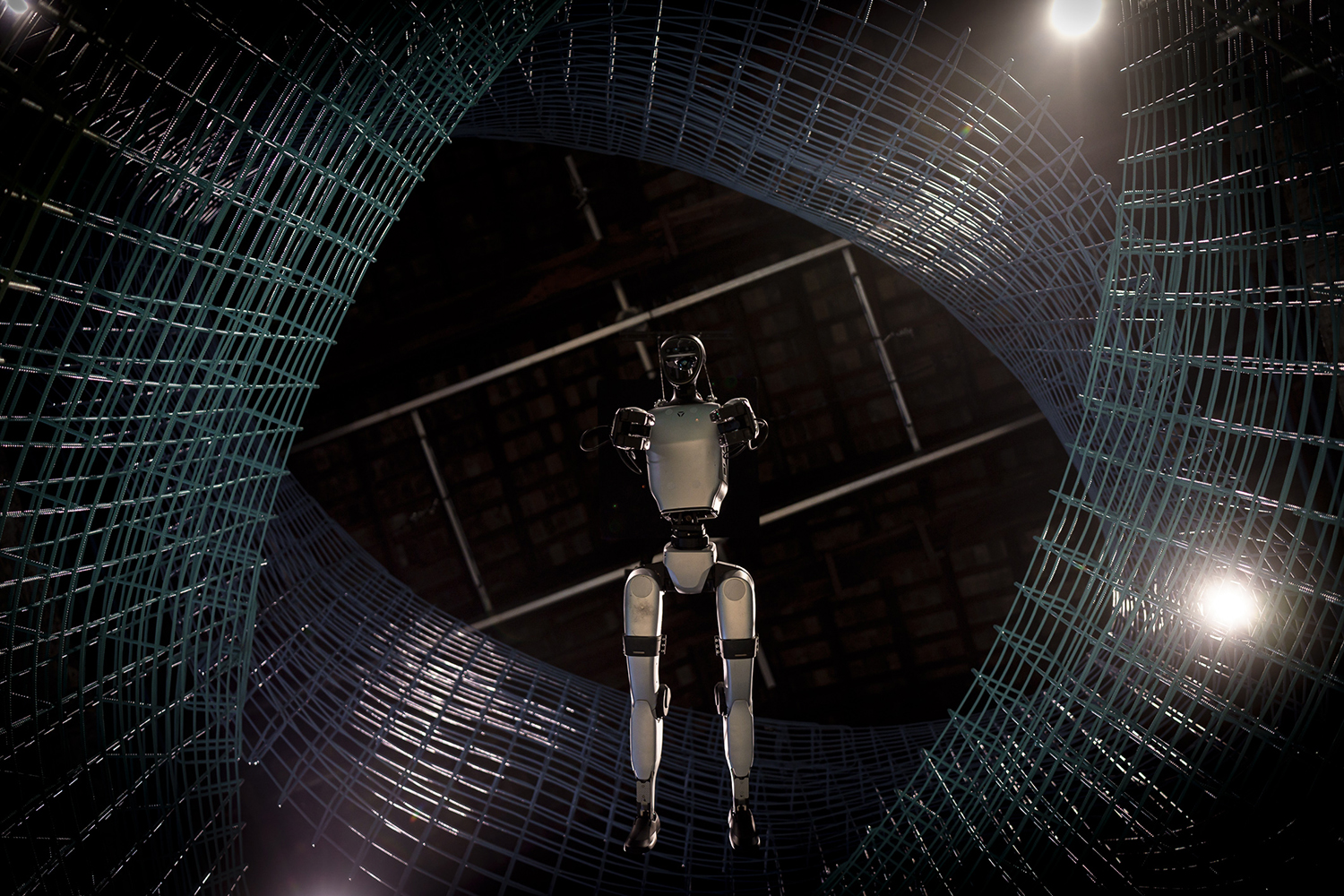

The entities given most prominence at the exhibition hall were robots. Humanoid robots respond to the actions of the audience by dancing with similar or metaphorically appropriated moves, or by hovering in the air with dreamlike facial expressions. The primary impression evoked by these works associated with such advanced technologies, is a sense of technological optimism. Although technology can be used as a tool for democratisation – the open-source tools pursued by Ratti’s MIT Senseable City Lab being a case in point – some of the installations that contribute to the spectacle at this Biennale evoke a subtly uncomfortable feeling by obscuring the inevitable fact that technological ‘progress’ ceaselessly drives and accompanies development. In particular, Ancient Future, a project by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and others, features Bhutanese artisans collaborating with robots to carve and trim a 6m-long wooden pillar—a work described as ‘a poetic exploration of harmony between Bhutan’s timeless artistry and cutting-edge technology’. However, seeing humans wipe their sweat while working side by side with robotic arms operating at an infinitely regular pace evokes a future in which not only the precariat (low-skilled, low-wage workers), but also even ‘high-skilled, low-wage workers’, will soon become unemployed. The class-discriminatory implication that robots will replace ‘specific’ humans is portrayed with extreme indifference. Meanwhile, there were also works that developed nature-friendly materials using advanced technology or reused materials that could have become waste. Among works traversing various fields and manners – such as programme and hardware, creation and reuse – based on the combination of technology and architecture, Tosin Oshinowo’s work stood out for its attention to the urban order spontaneously created by citizens. Alternative Urbanism: The Self-Organized Markets of Lagos positions architects not as problem solvers but as mediators, and it views the future not as predictable but as the result of unpredictable relationships.

A Robot’s Dream by Gramazio Kohler Research, MESH and Studio Armin Linke / ©Andrea Avezzù

Fourth, Is It Appropriate to Address Environmental Concerns at An Architecture Biennale?

The final question is the most monumental and fundamental, and one which will continue to be asked until fine dust levels consistently remain ‘very good’ every single day and until the glaciers in Antarctica freeze over once more. Since it became clear that architecture biennales produce a lot of waste, many alternative approaches have been proposed, such as using renewable materials and dismantlable units. The fact remains, however, that the most effective and simplest solution would be to stop holding them altogether. That said, the Venice Biennale, most especially, does not simply function as an exhibition but is also closely tied to the tourism industry, show business, and the establishment of architectural community network in Venice as a city. Ratti acknowledges that the Biennale, which is systematised around architecture, politics, and industry, has already begun and cannot be stopped. In doing so, he acts on what can be done at the base-level of our reality. ‘A Circular Economy Manifesto’, addressed to the participating authors of the Biennale, includes items such as ‘Design to maximise the use of reclaimed’, ‘recycled or renewable materials or existing exhibitions/assets, ideally locally sourced – aim for not less than 50% per weight’, ‘Design out hazardous and polluting materials that have a negative impact on the health of people as well as nature’. While the content may not seem particularly special, it should remain in place for future biennales as it has been officially documented. Additionally, in collaboration with the mayor of Madrid, Spain, which recently experienced the devastating Valencia Floods, he published a manifesto entitled ‘Intelligens: Towards a New Architecture of Adaptation’, requesting signatures from the general public in an attempt to spread architectural discourse on the environment beyond Venice and the architectural community. Here, Ratti argues that, in the face of the environmental crisis, architecture should neither be abandoned nor given up, but rather should learn from and adapt to ongoing changes in climate, technology, and society. Within the spectrum of giving up, adapting, and developing, Ratti sides with those who take action. What about us? What stance will each of us take in the face of the environmental crisis? This will inevitably influence how individuals evaluate this Biennale, each of its exhibits, and the Biennale industry as a whole.